In January 2020, all baseball fans could talk about was the Major League Baseball (MLB) report on the Houston Astros’ cheating scheme, which included sign stealing using hidden cameras and banging on trash cans to relay the pitch information to hitters. At the center of a media maelstrom over the revelation was former Astros pitcher Mike Fiers (above), who was named by reporters as one of their sources confirming how the Astros had cheated. Some supported his ethical stance, while others criticized Fiers for breaking the code of silence to reveal clubhouse secrets.

There has long been a code of silence among baseball players that whatever happens in the clubhouse, stays in the clubhouse. Choosing to blow the whistle requires overcoming that deeply engrained convention and extensive peer pressure to stay silent and not reveal former teammates’ misconduct. Fiers fulfilled his ethical obligation to blow the whistle on the cheating that he witnessed firsthand, taking into consideration the negative impact of electronic sign stealing on himself and his fellow pitchers and the integrity of MLB as a whole.

There’s a parallel between that and potential whistleblowers’ quandary when deciding whether to report misconduct in the business world given their possibly conflicting loyalties to the finance function, accounting team, CFO, and their company as a whole vs. the good of the profession and the company’s stakeholders. While Fiers was guided by his own sense of right and wrong, management accounting and finance professionals also have a code of conduct and the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice to guide them.

When you have an organizational or industry-wide corruption case, whether it involves a sports team trying to gain an unfair competitive advantage or a business trying to “cook the books,” it’s a special case for any individual to report misconduct. Because people who benefit from the status quo will criticize anyone who speaks up to reveal wrongdoing, whistleblowers operate in challenging circumstances.

“You’ve got a fascinating situation in an ethics sense, because you’re uncovering a corrupt culture,” said G. Richard Shell, the Thomas Gerrity Professor of Management and chairperson of the Legal Studies and Business Ethics Department at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “It isn’t as if there was an individual bad actor such as a rogue CFO who was manipulating the counting rules to whitewash the numbers and keep a growth story going or someone cheating on the expense account.

“It’s a moral hazard, people misbehaving because the system rewards them financially for it—batters get paid more for it because they’re getting more hits when they know what pitch is coming,” he said. “There’s a lot of social pressure to just keep your head down and your mouth shut.”

For Fiers, a combination of motivations outweighed the cost of stepping up, revealing him to be an ethical person who listened to his conscience and had the courage to speak the truth despite the potential negative consequences.

“When you’re an individual facing off against that level of bad acting, it requires strong ethics and significant motivation to step up and blow the whistle,” Shell said.

“In this case, moral discomfort combined with the position that this was disadvantaging pitchers, not just the individual saying ‘I’m not getting a fair shake,’ but he saw his duty to the younger generation of pitchers coming up, to the extent that due to this unjust practice, pitchers were not going to be treated fairly based on their level of talent,” Shell said. “Fiers thought, ‘I have a duty to make the game straight for the next generation, and I would’ve wanted someone to step forward if they were in my position.’”

Because professional sports are essentially entertainment, any discovered corruption within it will be public. As celebrities, athletes are adored by millions of fans, and the cost of being in the public eye when there’s a scandal can be painful. When an internal auditor at WorldCom or Enron blows the whistle after standards are violated, they might not initially be in the public spotlight if they report it to the board or a financial regulator, but when pension funds and investors see their stock go to zero and the whistleblower is testifying in front of Congress, there’s severe exposure to public scrutiny.

“Even when you’re being celebrated as a hero by one group, there’s pressure on you and your family, and the sign-stealing scandal is not that different from a financial scandal,” Shell said. “You can make tens of millions of dollars for a tip to the SEC [U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission], but you have to weigh the risks, including someone reading your name and outing you—even [for] a whistleblower involved with the current political moment, there are no guarantees of protections.”

Many times in these scandals, those in lower positions will be pressured from higher-ups to go along with the program, for example, executives leaning on bookkeepers to falsify entries. In the case of the Astros, the authorities in question were apparently not the source of the cheating; but they were complicit and did little or nothing to stop it.

In a lot of financial scandals, the authority is being exerted by higher-ups and the underlings are afraid of losing their jobs, so they use rationalizations such as “Just this once,” “I’m just doing what I’m told,” or “It isn’t my call.”

Sign stealing in baseball is much more an example of peer pressure than authority pressure, implying players are only part of the team if they go along with the sign stealing or at the very least keep quiet about it. It’s a powerful motive, so perhaps it isn’t surprising that we see such scandals in sports.

“A project team member knows when it isn’t being done the right way, but even when they know it’s wrong, the pressure to go along is intense,” Shell said. “Conflicting loyalties create a dilemma that’s felt by people who aren’t the instigators of misconduct but are pressured to go along with it because of loyalty to the firm and its investors and stock price, or the boss is under pressure to meet a goal or deadline, but then you’ve got the loyalty to your own conscience and your sense of who you are.”

Another aspect of the scandal that MLB must contend with is how sign stealing demonstrated that the rules of the game need to be updated to keep pace with the way that technology such as instant replay has evolved.

“Tech is so sophisticated and subtle and hard to detect that pitching signs are systemically vulnerable,” Shell said. “MLB may decide, ‘We’re going to change the rules of the game so that pitchers and catchers have a way to communicate pitch calling using technology.’”

REMAIN ANONYMOUS OR GO PUBLIC?

The Ethics & Compliance Initiative (ECI) surveys people in workplaces of all types, asking about common questions and the factors people have to weigh when deciding what to do about wrongdoing: Will it make any difference if they come forward? Will somebody listen? Will there be changes? Will the organization or industry/sport be better off if they come forward? What will happen to them if they sound the alarm and report the misconduct? Is this problem worth taking that risk? Is there a system such as an ethics hotline or helpline in place, and can it be trusted?

“For some, it can be a career-ending move to blow the whistle,” said Patricia Harned, CEO of ECI. “I suspect that it’s true for baseball players, and it’s absolutely true for someone blowing the whistle about financial fraud, corruption, or conflicts of interest.”

The sign stealing is a problem for MLB, even if you assume that the scope is limited to just the Astros and Red Sox, because it’s a classic case of wrongdoing, with people cutting corners or cheating and others being aware that wrongdoing is occurring and having to decide, “What am I going to do about it?” The ethics issues that a lot of other organizations, whether they are multinational corporations or large nonprofit organizations, face are applicable to MLB.

“Ethics and whistleblower issues are equally relevant in baseball as they are in business: the pressure to succeed, questions about whether to report wrongdoing, the fear of retaliation if you do report wrongdoing, reporting internally or providing an anonymous tip vs. going to the press or enforcement agencies,” Harned said. “All of those things that we consider to be ethics and compliance issues [that] are universal, they’re showing up in MLB.”

An important issue from an ethical perspective is, “What is the motivation of a would-be whistleblower?” People of integrity are motivated to protect the rights of others, such as investors, creditors, and clients, and realize they have an ethical obligation to fulfill this duty.

“In the case of Fiers, his actions do have an important public interest dimension because the sports public certainly doesn’t want a team that, arguably, won the World Series because of cheating,” said Steven Mintz, a professor emeritus of accounting at California Polytechnic State University. “If it was their team involved on the losing end, there’s no doubt they’d be upset and praise Fiers for blowing the whistle.”

Fiers seemed to have been motivated by a desire to clean up the game and level the playing field. He believed young players were losing their jobs because the Astros hitters knew what the pitches would be in advance, impacting the performance of the young pitchers and potentially resulting in them losing their jobs or being demoted to the minor leagues. Fiers has faced a wide range of reactions to his decision, from praise to condemnation to asking why he waited so long to report it.

“There are people in most organizations who are very interested in having people raise concerns because they recognize that it’s for the betterment of the organization,” Harned said.

“It’s great to see that most players, fans, team executives, and other stakeholders want fair play, where everyone is playing by the rules and the winners won because they played the best game, not because they’re cheating—Fiers has found some support,” she said. “Board members and senior executives recognize that the only way problems get stopped is if people come forward to report them.”

If people report misconduct outside the organization, then they get even more pushback, but often people become whistleblowers because they try to report incidents internally but are ignored or retaliated against.

In accounting, reporting a matter to the SEC under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 guarantees anonymity in virtually all cases, and whistleblowers are entitled to a financial reward if the information provided to the SEC is used to bring a successful action against the company.

FOUL BALL

Whistleblowers are often treated as if they’ve violated some sacred trust. Unfortunately, a prevailing attitude is that whistleblowers are rogue people as opposed to people acting out of loyalty to the organization and adherence to its code of conduct and ethical principles.

“The leading reason people become whistleblowers is there’s a problem that’s not being addressed and the only way to stop it is to go outside the organization,” Harned said. “It’s best for the team and the sport, but it’s hard for some people who are not in that position to see that.”

The reactions to Fiers’s decision to blow the whistle illustrate a common occurrence for whistleblowers in most fields. Some are hailed as trying to do the right thing, create fairness in an unfair system, and hold guilty parties accountable.

“We should admire such people because they’re motivated by righting a wrong,” Mintz said. “They’re willing to risk being singled out for being disloyal and even retaliated against.”

Should professionals who witness misconduct first report the matter up the chain of command within the organization, or is it ethically acceptable to go outside the organization before exhausting all internal lines of reporting? Fiers did the latter. He told sports reporters about the incident and blindsided his former teammates.

This approach is the essence of the criticism against Fiers, including that of Jessica Mendoza, an ESPN analyst, who said, “It’s very critical that this news [of the Astros stealing signs] was made public; I simply disagree with the manner in which that was done. I credit Mike Fiers for stepping forward, yet I feel that going directly through your team and/or MLB first could have been a better way to surface the information.”

Mintz thinks it’s unlikely that an accountant would skip this step, as Fiers did, and contact a reporter to blow the whistle on financial fraud. When accountants discover financial fraud in their company, Mintz believes that they should report it to their immediate superior, those above their manager, or, if necessary, all the way up to the audit committee of the board of directors. Internal reporting of the event in this manner is consistent with the IMA Statement.

LESSONS FOR FINANCE PROFESSIONALS

We can question the way Fiers went about blowing the whistle, his methods, and motivations because he didn’t actually report this conduct to the team management or ownership at the time, but he did take steps to go public. He allowed reporters to use his name and thus added credibility to the reporting on the issue, which helped to substantiate the charge.

“Business leaders set up compliance and control systems, create helplines, and hope people use them as designed, but reporting misconduct takes a tremendous act of courage,” Harned said. “People don’t always use the internal channels, but the goal is to create an environment where people feel safe raising concerns and reporting them.”

Management should ask: What are all the avenues that people will use to raise concerns, and are we paying attention to all of them so that we can adjust our policies and programs accordingly?

THE ROOT CAUSE

After an unethical incident like sign stealing happens, the process doesn’t end with conducting an investigation and punishing those involved. It’s important to do a root-cause analysis: Why did this happen in the first place, what is it about the environment that facilitated this, and what caused the employees and others involved to act in this way? Do we have the proper systems in place to report misconduct?

“I’m hoping MLB thinks about whether they have the necessary reporting systems in place and trains coaches and managers how to receive and respond to reports of misconduct so that they know what to do and handle them effectively, and that’s true for every organization,” Harned said.

Another important business ethics point is an accounting or finance professional’s loyalty to the organization, a boss, or a colleague shouldn’t be used as an excuse to mask ethical obligations such as honesty, integrity, and transparency.

“Accounting professionals are in a position of trust,” Mintz said. “This means they should fully disclose all the information investors and creditors have a right to know about the actions of an organization. Their ultimate responsibility is to the public.”

In the early 2000s and post-2008, we learned of massive amounts of financial fraud that was covered up internally, and many people lost a lot of money because of the negative effects on stock prices once the wrongdoing was publicly disclosed. The reputation of corporate America was tainted, and the public lost confidence in financial institutions.

“Imagine if Fiers said nothing and no one else came forward—the cheating scandal may have persisted,” Mintz said. “We already know the Red Sox were involved in a similar case—the sports public may have lost confidence in the integrity of baseball had it not cleaned up its act after disclosure of stealing signs.

“MLB was able to tamp down the criticism because it acted swiftly in suspending the [then] Astros manager A.J. Hinch and [then] general manager [Jeff Luhnow] for one year,” he said.

NECESSARY PUNISHMENT

MLB had to make it clear that it’s wrong for anyone associated with the game to turn a blind eye to unethical conduct and to encourage those who know about improper actions to come forward and not fall victim to the bystander effect, when a player stays silent hoping someone else will go public with their knowledge of wrongdoing. The league had to send a clear message that cheating isn’t allowed and offenders—both individuals and the organization—will be held accountable.

This sort of sanction—suspensions at the management level and loss of draft picks—acts as a deterrent to top management at all teams to be more careful with such ethics violations. But many said that MLB’s punishment of the Astros and Red Sox didn’t go far enough. They both got to keep their World Series titles, and no individual players were punished. (Note: During its investigation, MLB agreed to offer immunity to players in return for honest testimony, which has become a source of controversy itself.)

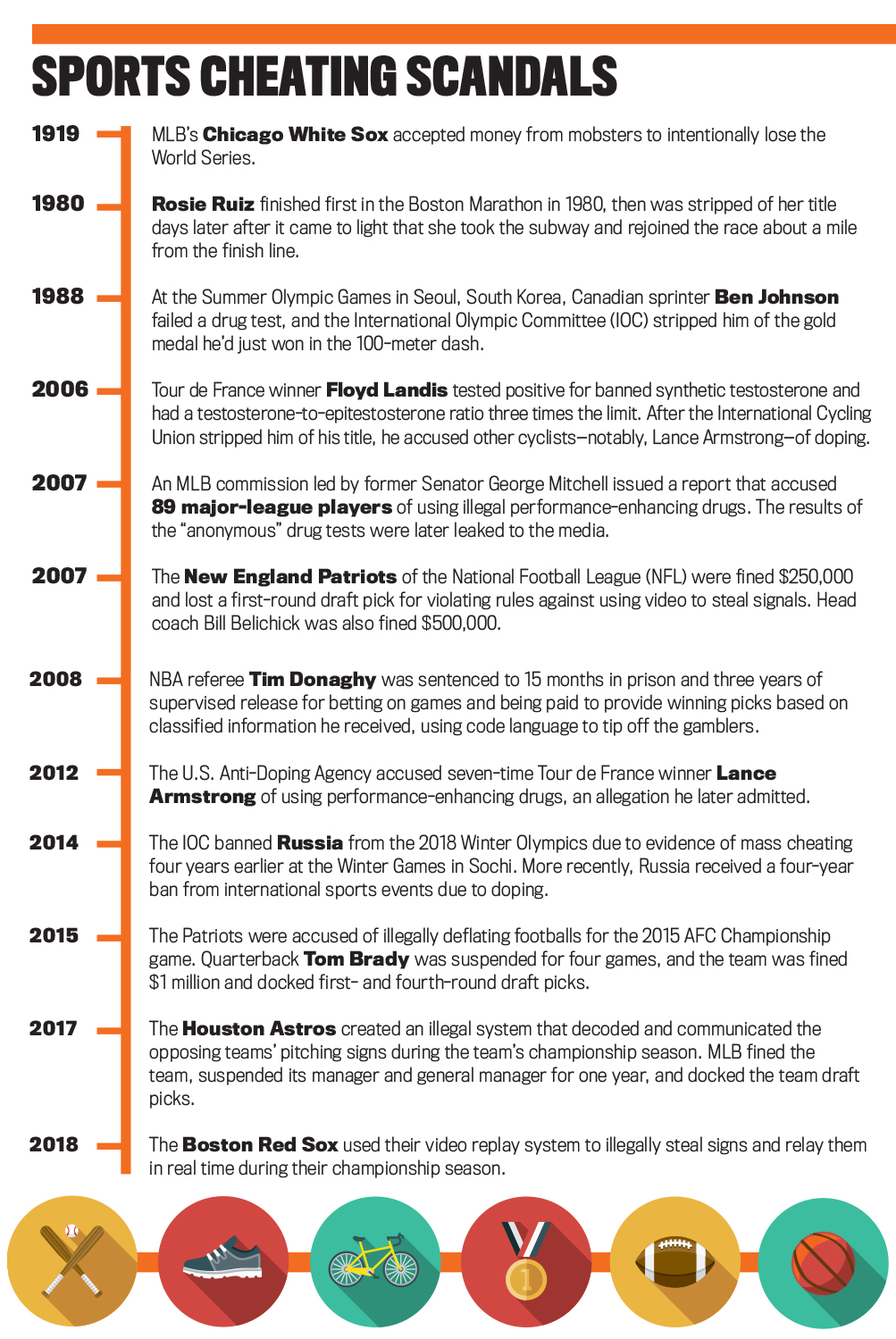

“You think the perpetrators should be punished, and then there are people who are complicit and stayed silent, so when you punish the management, that’s a useful deterrent, but the Astros have been rewarded with a world championship that they achieved through corrupt means,” Shell said. “For the game to retain its legitimacy, they should have done something to correct the competitive outcome, remove the championships, take them away—Lance Armstrong was stripped of his Tour de France titles, and the NCAA [National Collegiate Athletic Association] has vacated wins and championships.” (See “Sports Cheating Scandals”.)

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

“It’s a corrupt, illegitimate championship, so it gets taken away—there’s a deterrent,” he said. “‘If we win that way, we’re ultimately going to lose, so it isn’t worth it’—you empower the players with consciences with a great argument not to do it, but sanctioning management, not players, makes the latter feel like they got off scot-free.”

Are MLB’s punishments for the Astros and Red Sox sufficient to encourage them and other baseball organizations to become ethical and for individual players to call out unethical conduct? Time will tell.

The individuals who commit an offense may do so because the culture of their organization allows it to occur or fosters an environment where it’s acceptable to stand idly by and do nothing to prevent unethical actions, and that certainly applies to the Astros and Red Sox.

“Punishment is necessary to change the culture and elevate the interests of the stakeholders…above the pursuit of self-interest, for example, materially misstated operating results to achieve a bonus or winning games that the team might otherwise lose,” Mintz said. “The organization is also responsible for the actions of these individuals because it should set an ethical tone at the top that makes it clear cheating will not be tolerated.”

What matters most is people who engage in wrongdoing are punished—other people need to know that there are real consequences for unethical behavior.

“You have to let others in the organization and the industry know that if wrongdoing happens, there will be a fair and objective investigation to understand all the facts, consideration given to the magnitude of what happened, and punishment handed out,” Harned said.

“It’s important for others to be confident that if they come forward and speak out about misconduct, they will be treated well and protected as a whistleblower,” she said. “It’s less about the specific punishment and more about the fact that action was taken.”

AN OVERVIEW: MLB SIGN-STEALING SCANDAL

Four people employed by MLB’s Houston Astros in 2017 said that, during its World Series-winning season, the team stole signs in real time with assistance from the operations staff.

The Astros trained a camera on the opposing catcher’s signs (the fingers and other signals he displays to a pitcher so the two can communicate about the type of pitch that will be thrown next) and then connected the camera feed to a monitor on a wall near their dugout. Team employees and players watched the screen during the game to decode the signs. They communicated the expected pitch type with a loud noise, typically banging on a trash can in the tunnel that runs between the dugout and the clubhouse, to indicate to the hitter what pitch was coming.

The league fined the Astros $5 million, docked the team’s first- and second-round draft picks in 2020 and 2021, and suspended the manager, general manager, and bench coach for one year each.

The Boston Red Sox also engaged in illicit sign stealing in 2018, with cheating paving the way for their World Series championship run. During the investigation, none of the team’s players spoke out about the misconduct. As punishment for their sign-stealing violations, MLB suspended for one year a scout who monitored video replays and docked the club its 2020 second-round draft pick.

Source: The Athletic

MORE FROM SF:

“Preparing for Whistleblower Complaints,” September 2020 “Increase Your Whistleblowing IQ,” January 2020 “SEC Whistleblower Program Expands,” November 2019 “Is Your Company Empowering Whistleblowers?” January 2017

November 2020