On its surface, this latest report suggests an increase in unethical or illegal behaviors by individuals that correlate to increased whistleblower activity and enforcement action.

As occurrences of fraud continue to increase, many organizations may be involved in some type of whistleblowing investigation—whether it’s from an outside agency or in response to a tip received through an internal program. Vetting and investigating these complaints is critical, and companies need to not only assess their readiness for these types of investigations, but also understand how technology such as AI and analytics can help.

There are a number of questions finance leaders should be asking themselves in order to ensure their organizations are prepared and protected.

Q: What should the number of whistleblower reports suggest to the C-suite and, if concerned, how might organizations prepare proactively for these types of investigations?

Simply put, misconduct appears to be on the rise. And when there’s more reportable behavior, there will be more reports. Significant financial incentives associated with successful enforcement actions also lead to more tips.

To best be prepared for whistleblower activity and related investigations, the C-suite should (1) understand and be alert to potential whistleblowing motivators, (2) have the appropriate auditing tools available, and, most importantly, (3) cultivate a corporate culture that prioritizes both ethical behavior and good employee relationships.

1. Motivators. Understanding potential motivations of a whistleblower—which in many ways mirror those that persuade individuals to engage in bad behavior—can provide insight into employee activities and heighten sensitivity to red flags for potential wrongdoing. The acronym MICE captures possible rationales: money, ideology, compromise, and ego/extortion:

- Money. Loss of income because of layoff, financial crisis, corporate decisions, or the promise of a big payday from whistleblower payouts can all be more than enough reason to act.

- Ideology. Every organization has people willing to go to the mat for the good of the company. Likewise, there are those with uncompromising ethics who will follow their moral certainty wherever it may lead. While this motivation often comes from the right intention, individuals in this category may have unrealistic expectations about the legal requirements that employees or organizations are required to meet, or they may even see issues where they don’t exist.

- Compromise. Individuals cornered because of their own questionable behavior may know others who are engaged in illegal or unethical behavior as well. In order to save themselves, they will be motivated to identify other bad actors.

- Ego/extortion. For an individual who feels underappreciated and has knowledge of questionable or illegal behaviors—especially of their superiors or rivals within the organization—providing compromising information for self-promotion is the ultimate ego boost.

2. Auditing tools. The development of a robust internal auditing mechanism to identify reportable behavior when it happens should be foremost among the proactive solutions considered by a company, and most companies have such mechanisms in place.

AI and analytics tools can be powerful additions to existing auditing processes, especially when targeted with discretion and used wisely. Acting as a force multiplier for skilled auditors, AI systems can leverage the auditor’s own experience via training of the AI system to handle tasks that are more mundane, freeing the auditor to address more complex aspects of an investigation. For instance, good uses of this technology include deployment of AI systems for the monitoring of financial transactions to identify irregularities or to monitor electronic communications (email, texts, instant messages, and social media) to identify potential bad actors.

Although AI tools are an option to consider, they shouldn’t be the only tools used. Importantly, they’re best at identifying illegal activity after the fact and are only as good as the data used to train their underlying algorithms.

3. Corporate culture. In parallel with other considerations, the impact of a positive corporate culture shouldn’t be underestimated. Strong reporting policies and responsive leadership can go a long way toward mitigating both bad behavior and complaints, and proactive engagement sits well with enforcement agencies. Whistleblower and ombudsman programs to identify, investigate, and prevent reportable behaviors are useful to bridge the gap between the purely digital evidence that auditing systems may be able to catch and things like discreet conversations and rumor-mongering that might take place at the coffee machine.

If financial incentives associated with legitimate and enforceable actions by the SEC are promoting whistleblower actions, doing the same at the corporate level might have a similar effect. Independent investigators can ensure impartial evaluation of facts in order to reach conclusions that are fair to all. If an investigation uncovers illegal activity, the company can then self-report to the appropriate enforcement agency. This could mean avoiding or minimizing exposure for the organization and any executives not implicated by the internal investigation.

Q: What are the general challenges involved in vetting these types of allegations? Is a whistleblower investigation different from any other type of investigation?

By nature, whistleblowers are insiders. They have some level of access to company information that outsiders don’t, and, typically, the basis of the allegations is information obtained as part of their job responsibilities. From the outset, this gives their claims more credibility than those of consumers or competitors.

The greatest challenge in conducting an internal whistleblower investigation is determining if the allegation is true. But the procedural aspect of a whistleblower investigation is very much the same as any other investigation that corporations are subjected to, such as quarterly and annual disclosure of financials, as well as investigations related to offering fraud, manipulation, insider trading, trading and pricing manipulation, or the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), all of which are highly congruent with whistleblower investigations.

These investigations all strive to answer several key questions: What was included in the disclosure? Was the disclosure obtained voluntarily or under duress? Was the disclosure sufficient to show a pattern of behavior? Was that behavior illegal or fraudulent? Did the disclosure match what was reported by the whistleblower? Do corporate practices in the industry that are commonplace and accepted seem unethical to the uninitiated? Did any of these findings cross the line into behavior that warrants enforcement action?

Finding the evidence of wrongdoing (or lack of it) is critical. Since most evidence is electronic these days, an internal team to investigate reported or suspected financial crimes requires a diverse set of skills, including knowing how to query and evaluate everything from common spreadsheets to SQL and NoSQL data sets, for example.

Unstructured data (like email, text messages, and documents) requires an entirely different set of skills for identifying key facts to support or refute claims made. The search for such information requires strong linguistic skills paired with advanced search and retrieval software, which goes beyond what the average IT or legal department has available. Even the most seasoned IT professionals may not have experience with different methods of indexing content, which could derail efforts from the start since how the unstructured data is indexed and searched is important to success.

The ability to untangle often complex computer code is also necessary. Sophisticated programs built to interact with structured data and do things like trigger buy and sell orders, initiate transfers of funds, or otherwise manipulate the data in any number of other ways may require auditing. This is especially true if there’s a complex network of transactions queued across multiple platforms, as in the most intricate money-laundering schemes.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Q: What kind of analysis can determine whether there has been an ethics or compliance violation?

AI and advanced analytics can be useful tools in the identification of outlier events, which often suggest suspicious activity or noncompliant behavior. Using advanced text analytics can assess communications to uncover unethical behavior. Different analytics approaches can be deployed depending upon the nature of the data.

When it comes to structured data analytics, AI and analytics tools can be set up to look for transactions that exceed norms, possible indicia of suspicious behavior. For example, rounded numbers, transactions with vague or missing detail, rush requests, unusual cash disbursements, or transactions that circumvent typical approval processes may be suspect.

Likewise, analytics tools can uncover unusual transaction volumes. Calculating rolling historical averages over prior periods can reveal when larger or smaller volumes of transactions are executed during a recent period. The same is true for the value of transactions; high volumes of low-value transactions can be red-flag events, suggesting an investigation into the individual initiating those transactions.

Transactions taking place in unusual locations might also be suspicious. Doing business in countries such as Russia, North Korea, or Iran are obvious examples. Yet doing business in new locations that seem unlikely is equally concerning. If an organization historically has only conducted business in North America and suddenly expands into South America or Asia—or just as suddenly stops doing business in those locations—it should be another warning bell for internal investigators.

Outlier events in general warrant a second look to ensure there’s no impropriety. Any of these red-flag events, when paired with user logs, provide sufficient reason to investigate the individuals tied to these activities.

Other approaches can be employed for unstructured data analytics. Applying analytics against unstructured data (documents, email, and other messaging) can be revelatory, exposing use or changes in language that may indicate unethical or noncompliant behavior. Use of keyword language filters that forward emails to legal or HR for ethics concerns are helpful, but using more complex analytics with linguistic expertise behind them enables more subtle assessments. Depending on the complexity of the IT infrastructure, enterprise-wide indexing options exist that enable deployment of language filters for monitoring and analysis.

Q: Is there a way to be proactive in the investigations process to contain a potentially inflammatory situation?

There may be a temptation to engage in a full-fledged investigation at just the hint of a problem, but a more cost-efficient and faster way to be proactive is to scale an action to the importance and scope of the potential exposure. Especially when electronic data is involved, begin with the narrowest data selection that could be informative and only expand the inquiry as the situation warrants.

This could mean collecting transaction data for a specific day, email for a limited list of people of interest, or, in the case of a whistleblower tip, interviewing the whistleblower. Determining if the tip was the result of rumor, suspicion, repeated behavior, an isolated incident, or something else entirely would all help inform the scope of the initial investigation. The organization needs to complete its due diligence in all circumstances, but observed behaviors would warrant a deeper dive earlier on than rumors or mere suspicion.

Also use sampling methodologies to limit scope and control costs. When focusing on a data-driven investigation, minimizing the scope and amount of data for review is the best way to manage costs. One way to do this is by using a sampling methodology to evaluate the data population in question. By reviewing a representative sample of records, the investigator can then extract generalizations about the overall population. If the review unearths incriminating records, a more comprehensive investigation should follow by expanding the inquiry in a targeted direction.

Even if the review surfaces nothing explicitly incriminating, suspicious or questionable records should also result in an expansion in search scope. The key here is to only expand the search scope if there is a reason to do so. If early sample tests don’t warrant further investigation, then initiating proactive communications to manage the narrative, either with regulators or as part of a public relations campaign, may be the next logical step.

If an investigation’s scope does expand, data volumes will naturally increase. Technology can be used to reduce the investigatory load. In email review, for example, well-crafted keywords and de-duplication or email-threading tools significantly reduce data volumes for review. Likewise, machine-learning AI tools that can learn from human input about the relevance of documents can be cost-effective by propagating relevance decisions to duplicate documents or predicting how human reviewers would code similar documents.

This type of technology (referred to as technology-assisted review, or TAR) can expedite the review of electronic data, saving time and expense by limiting the number of records an investigator might need to put eyes on, thus amplifying the impact of each human decision while at the same time helping to unearth records critical to the investigation. In combination, this process leads to a more efficient workflow, accelerating resolution of the investigation and enabling any necessary remediation to occur more rapidly.

It’s also critical to look beyond the data. As scope expands, take proactive and precautionary containment steps while the investigation process is completed. Limiting or prohibiting IT access for suspect individuals should be considered to prevent deletion or theft of proprietary information and to enhance tracking and collection of their data going forward.

If appropriate, adjusting the reporting structure, physical location, hours, or client access for those under suspicion are warranted countermeasures to prevent further wrongdoing. Of course, this delicate balancing act requires the full cooperation of HR and legal in order to not derail the investigation or tip off the involved individual(s). The rights of both the organization and the employee must be considered at all times to foreclose the possibly of further claims.

Q: Are there differences among analytics and AI tools that are important to know about?

Generally, off-the-shelf analytics and AI tools perform well in completing standard business intelligence data gathering and analysis. Each has different bells and whistles, with the important differentiators being how well the people deploying or using the tools understand how they work, know their respective interfaces, and understand how to maximize their utility.

While these tools have become the go-to solution for day-to-day business analysis in many organizations, most desktop software tools have similar shortcomings. Specifically, they are generally one-size-fits-all tools that effectively cover the most common use cases and aren’t positioned to handle the unique needs associated with whistleblower investigations. While tools like Tableau or Power BI are great for creating visualizations to illustrate everything from quarterly sales to market trends year over year, they lack the ability to sufficiently query the underlying data.

Additionally, while there are specialized tools available for virtually every industry (e.g., IBM’s Analyst’s Notebook for law enforcement and fraud investigators), the most prevalent analytics and AI tools available today aren’t industry-specific and instead require users to adapt to the limitations of the software. Further, the vast majority of these tools are only capable of working with structured data; they can’t interact with email or other standard business documents with unstructured content, thus prohibiting any kind of meaningful text analysis.

While these tools can definitely assist in an investigation in their present form, they will usually fall short when it comes to the heavy lift typically required of whistleblower investigations, which generally benefit from both text analysis and the ability to thoroughly audit structured data.

On the plus side, though, customized analytics tools for a company are readily available, either through in-house development or by contracting with a third party. Likewise, solutions can be housed on-site or in the cloud, with many cloud storage providers offering environments with a laundry list of analysis tools built in and ready to use.

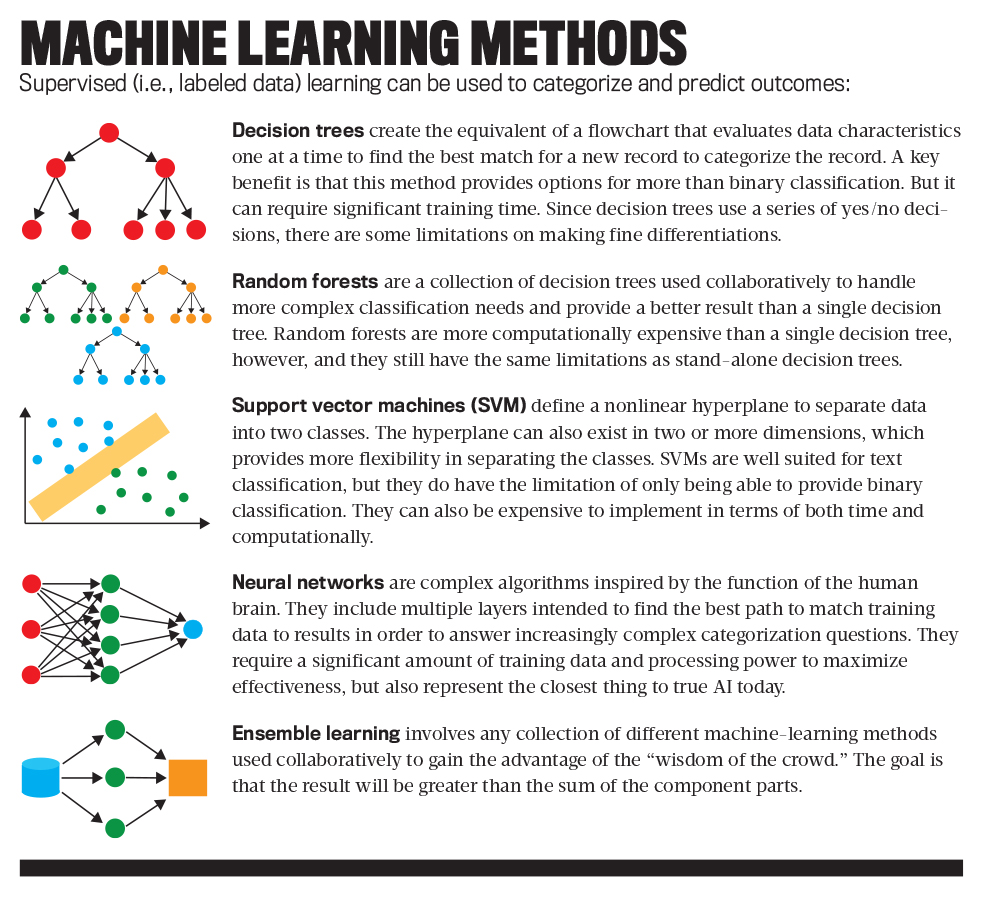

The good news is that the world of AI is rapidly evolving. Machine-learning algorithms have gone from decision trees and support vector machines that were state-of-the-art a few years ago to deep neural networks that are the current bleeding edge. An educated in-house team is important in adjusting to new developments; further innovation is inevitable, so if an organization is going to invest in AI, there will be an ongoing need to remain current with these advances to continue to justify the investment.

Finally, looking toward the future, processing power and the efficiency of AI to classify data will improve, both in the way physical machines crunch the numbers and how the underlying software can create computational efficiencies. Another future improvement will be in the world of image analysis, which will be able to better use security footage in conjunction with facial and body language recognition algorithms to identify people behaving suspiciously.

Likewise, natural language processing currently used in chat bots and binary content classification has the potential to evolve for immediate analysis of the words people write and speak. This could be a powerful tool in understanding their actions and motivations. How all of this will impact both whistleblowers actions and company investigations remains to be seen.

A FORENSIC DATA INVESTIGATION

What happens if someone has modified, deleted, or stolen incriminating data?

If there’s a suspicion that key data is missing or has been modified, a forensic analysis may be called for. Standard tools (e.g., FTK Imager and EnCase) are able to identify changes made to files, file systems, and mobile devices. They can also find fragments of deleted files and confirm if external storage devices were connected to a computer, which can build a case supporting a data theft scenario.

Likewise, digital fingerprints can be detected for personal emails sent from the company’s email system or from an employee using personal web-based email or cloud storage applications from a company computer—even when using so-called private browser windows. A review of data backups can also be helpful in finding supposedly “lost” data or in identifying deletion dates.

If data theft is confirmed, law enforcement can compel the collection of suspected devices where data may reside for forensic review to determine if it currently or previously existed on the device. Likewise, if a USB device was used to transfer stolen data to a new network, such as in a situation involving theft of intellectual property, a log of that transfer would also exist and could result in further action involving the individual’s new employer.

September 2020