It isn’t unthinkable. Computer scientists have described a variety of circumstances that could knock large sectors of the internet offline, but there are built-in safeguards against this happening. Because of its global size and the systems in place to redirect traffic around any broken links, it looks like it could survive anything less than a simultaneous attack on its entire structure of countless connected networks.

That kind of all-encompassing assault is unlikely according to Paul Levinson, professor of media and communications at Fordham University. “It would be very hard for the entire internet to crash based on an important systems theory principle called redundancy. There are so many backup systems, so many workarounds, so many different ways to get from point A to point B. All these come online instantly and automatically if the system fails.” The internet isn’t a single network, but rather a decentralized web of individual networks handling millions of connections at any given moment.

It isn’t invincible, though. There are technical attacks that could be disastrous. Patrick Juola, a computer science professor at Duquesne University, describes a possible attack on the root servers that serve as the internet’s address book system—the DNS (domain name system managed by ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers). “If those computers could be disabled—whether by power outage, a virus, or physical damage—most computers would not be able to find each other to send messages. In practical terms, the internet would simply stop working.”

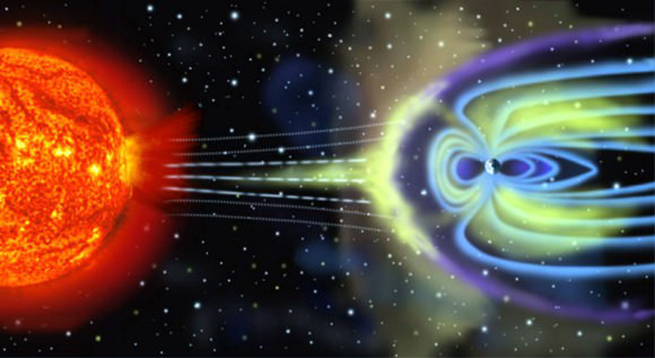

And there are natural disasters that also could create havoc. Juola explains one such interplanetary electronic disaster. “A sufficiently powerful [solar] flare could produce an electromagnetic solar pulse [EMP] that would shut down most of the computers in the world. While some systems are protected against EMPs, any human-built protection is only so strong, and the sun can be a lot more powerful.”

An internet crash resulting from this type of solar flare sounds like science fiction or one those once-every-10,000-years events, but it isn’t. The worst recorded X-class (highest level) solar flare, called the Carrington Event, was a coronal mass ejection that produced a geomagnetic storm that spread across the earth over two days, September 1-2, 1859.

Geomagnetic storm rendering: NASA

Geomagnetic storm rendering: NASA

The storm produced auroras around the world. The ones in the northern hemisphere reached as far south as the Caribbean, and they were so bright people in the northeastern United States could read newspapers by their light at night. The major electric utilities affected were the telegraph systems that failed across Europe and North America. The telegraph pylons threw sparks and shocked operators still at their keys. In 2013, researchers from the Lloyd’s of London insurers and the Atmospheric Environmental Research in America estimated the cost of a Carrington-scale event would be $0.6-2.6 trillion in the United States alone.

The frequency of recorded CMEs isn’t very encouraging. Less powerful geomagnetic storms were recorded in 1921 and 1960, and a 1989 storm disabled power over large sections of Quebec. Then, on July 23, 2012, a “Carrington-class” solar superstorm narrowly missed the earth by nine days when it crossed the planet’s orbit.

COVID and the Internet

Lending credence to Nietzsche’s observation in that “during times of war, what doesn’t kill you will make you stronger,” the internet is bearing up admirably under the worldwide increases in demand. In an April 2020 posting to the MIT Technology Review, Will Douglas Heaven, senior editor, AI, discusses “Why the corona virus lockdown is making the internet stronger than ever."

The arrival of the virus in the West generated a 25% increase in online traffic between January and late March. Cloudflare, a network infrastructure provider in the U.S. noted skyrocketing demands for videoconferencing software like Zoom, which exceeded all of its 2019 requests in just the first two months of 2020. Stay-at-home entertainment and online gaming also exploded.

During the first weekend in April, at one point, more than 24 million players were logged on to Steam, a popular online game store, all at the same time. Online gaming has experienced a 25% increase since February 2020, people are working and grocery shopping from home, kids are attending classes, streaming services are flourishing as theaters have closed, and family visits are relocating to the pipes of the internet.

Heaven describes the effects felt on the network. “There are understandable signs of strain: Wi-fi that slows to a crawl, websites that won’t load, video calls that cut out. But despite the odd hiccup, the internet is doing just fine. In fact, the COVID-19 crisis is driving the biggest expansion in years.” Credit the wisdom of the distributed nature of its architecture and the opportunism of those understanding that now is the time to expand.

Heaven points out that the growth is varied by region. The Cloudflare data shows an increase of internet use of about 40% in Italy and far less in South Korea, where “people were already heavy internet users throughout the day.” Also, Cloudflare maps “reveal how human activity has left city centers behind and decamped to the suburbs.”

After lobbying efforts by Thierry Breton, the EU’s commissioner for internet markets, many video-streaming companies, including Netflix, YouTube, Facebook, and Disney+ “all agreed to cut the picture quality of streamed video in Europe to avoid adding to the strain.” A wise decision when you consider streaming is “more than half of the internet’s traffic, according to analysis by internet hardware firm Sandvine.” Also pitching in are Sony, Microsoft, and Valve, who have decided to cut back on sending out updates for their video games or are issuing them only in off-peak hours.

Looked at in its entirety, Heaven believes the internet is adjusting and doing well. He also cites the judgment of two companies that monitor connection speeds around the world. The nonprofit RIPE NCC (Network Connection Center) in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and Ookla, a global leader in internet testing, data, and analysis, based in Seattle, Washington, both “show minor slowdowns, but little change overall.”

Monitor Your Own

Ookla offers a great free app that will test the speed of your own internet connections. It finds the closest, fastest server for your service and then checks upload and download speeds, ping (time it takes to connect to the server when you click), and jitter (fluctuations). The app is called Speedtest from Ookla, and you can get it from whichever store provides the apps for your computer—iOS, Android, Windows for phones, tablets, laptops, and desktops. Expect to get different speed results from your different devices and computers.

Some have better radios than others, and you’ll notice dramatic differences at different times during the day. The app keeps a log of your tests, allowing you to choose when the best times for streaming or multiple connections might be each day. Speedtest will also show you a map of the coverage from your service provider in your locale and wherever you might be traveling, as well. It will show you the coverage maps of other service providers.

The hardware, the software, and the basic idea on which the internet architecture operates are all settling in—adjusting and even expanding during the largest pandemic in a century. For now, one of the largest collaborative efforts of mankind is getting stronger.