Finance and accounting professional organizations around the world such as IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) emphasize the importance of ethics. The IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice, for example, serves as an ethical guide and details the importance of honesty, fairness, objectivity, and responsibility. Ethical leadership can cultivate the growth of these individual traits throughout the organization, and civility is an important part in fostering such ethical modeling.

In the article “Cultivating Ethics in Business,” Babu I. Razack stated, “An important trait of ethical leadership is giving respect to everyone regardless of rank by listening attentively, valuing their contributions, and being compassionate while considering opposing viewpoints” (Strategic Finance, June 2021). Civility goes beyond the act of being polite and showing regard for others. It includes the ability to disagree with others without disrespect, considering the opinions of others, valuing their positions, and truly listening.

What impact does incivility have on the finance and accounting profession, and what strategies can organizations use to combat incivility in the workplace? We surveyed finance and accounting professionals to examine incivility in the workplace and its resulting impact on employees’ overall job satisfaction and turnover intent. The results have implications for supervisors and underscore the importance of implementing organizational strategies to address incivility.

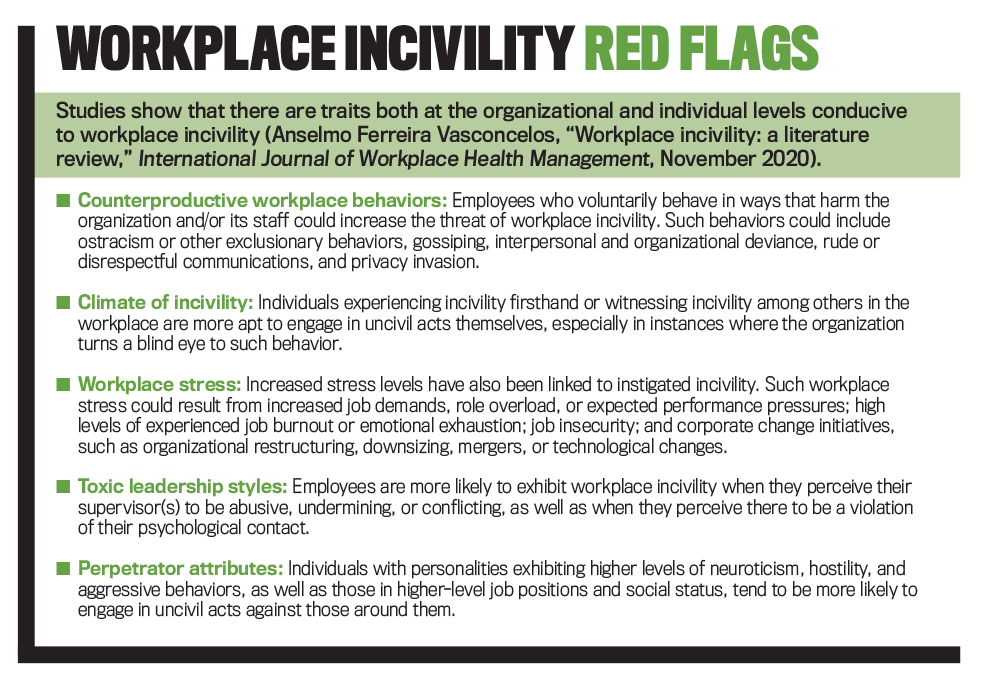

Though data may vary internationally, the study Civility in America 2019: Solutions for Tomorrow reported that the average American encounters uncivil acts on average 10.2 times per week and 93% of Americans believe incivility is an issue in the United States.For those who believe this number is high, incivility blindness may have set in. It doesn’t take much time or effort to witness uncivil acts; simply visit the comments on any social media platform, watch the news, or pay attention while dining at a local eatery. Does the incivility we witness in everyday life translate into uncivil workplaces?

Although some may believe the workplace to be an escape from the incivility witnessed in daily life, this isn’t always the case. The Civility in America study also noted that 89% of respondents indicated the workplace is very or somewhat civil. This contrasts with the study results of Christine Porath and Christine Pearson (“The Price of Incivility,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 2013), who surveyed thousands of workers over a 14-year period and found that 98% of respondents had experienced uncivil behavior in the workplace. These studies draw attention to workplace incivility issues potentially impacting the finance and accounting profession.

WHAT IS INCIVILITY?

Porath and Pearson define incivility as “the exchange of seemingly inconsequential inconsiderate words and deeds that violate conventional norms of workplace conduct” (“The Cost of Bad Behavior,” Organizational Dynamics, January 2010). Elsewhere, Pearson and Lynne Andersson define workplace incivility as “low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect. Uncivil behaviors are characteristically rude and discourteous, displaying a lack of regard for others” (“Tit for Tat? The Spiraling Effect of Incivility in the Workplace,” Academy of Management Review, July 1999).

In other words, incivility comprises small acts that are perceived by others as demeaning or that make them feel unimportant or underappreciated. Small acts in the workplace could include ignoring a coworker’s or employee’s opinion, dismissing a coworker’s or employee’s input on a project, talking down, making derogatory remarks toward a coworker or employee, texting during a meeting, excluding coworkers or employees from workplace activities, and so on. Some may seem inconsequential, such as texting during a meeting, but these acts may affect others in a significantly negative way. Perceived uncivil actions have major consequences in the workplace. Porath and Pearson say the cost of incivility in the workplace can be high, and their studies found that of the individuals experiencing incivility:

- 48% experienced decreased work effort,

- 80% lost time worrying about the incident,

- 78% indicated a decline in their organizational commitment, and

- 66% indicated declined work performance.

This shows that seemingly inconsequential words or deeds may have lasting implications for an organization. Workplace incivility is an issue that the finance and accounting profession shouldn’t ignore. Our survey results of 190 finance and accounting professionals found 74% of respondents had experienced at least some form of incivility from a superior in the past year, with 24% reporting incivility occurs occasionally or often in the workplace.

Employees look to supervisors as models of acceptable behaviors within an organization. This tone at the top permeates an entire organization, setting the organization’s general ethical climate. According to Bill George, senior fellow at Harvard Business School, “If people see their leaders as trustworthy and willing to learn, followers will respond very positively to requests for help in getting through difficult times.”

Experiencing incivility in the workplace at the hands of a supervisor may lead to employees displaying acts of coworker incivility. We found 62% of survey respondents indicated they had experienced some form of incivility from a coworker in the past year, with 21% reporting this incivility occurred occasionally or often in the workplace. This leads to the question: Does workplace incivility experienced by finance and accounting professionals negatively impact their job satisfaction and work performance, ultimately leading to their increased intent to leave their companies? Our survey results point to yes on both accounts.

SURVEY RESULTS

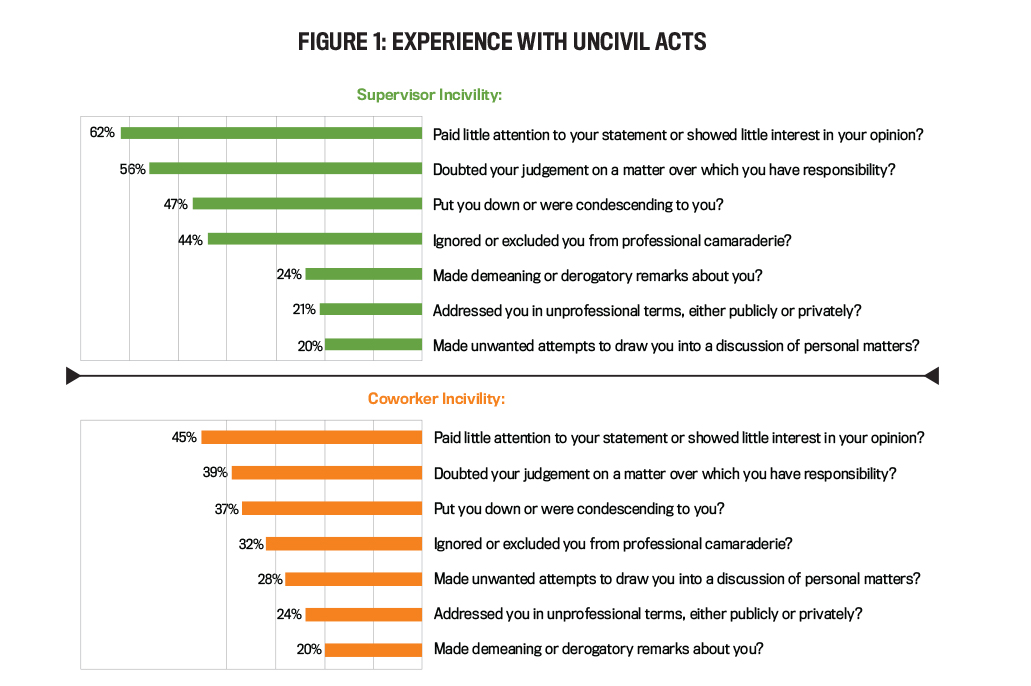

We used the Workplace Incivility Scale (WIS) to measure 190 respondents’ experiences with workplace incivility. The WIS is a common measure of experienced incivility asking respondents to indicate, using a four-point Likert scale, how frequently they have experienced seven uncivil acts (Lilia M. Cortina, Vicki J. Magley, Jill Hunter Williams, and Regina Day Langhout, “Incivility in the Workplace: Incidence and Impact,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, January 2001). Our survey asked these finance and accounting professionals to indicate which of the following seven uncivil acts they had experienced from supervisors and coworkers within the past year:

- Paid little attention to your statement or showed little interest in your opinion

- Doubted your judgement on a matter over which you have responsibility

- Put you down or were condescending to you

- Made demeaning or derogatory remarks about you

- Addressed you in unprofessional terms, either publicly or privately

- Made unwanted attempts to draw you into a discussion of personal matters

Figure 1 shows the frequency of the uncivil acts the respondents reported experiencing. While it’s promising that a good percentage of respondents indicated they’ve never experienced these acts of incivility, several of these behaviors are nonetheless prevalent in the workplace. Regarding incivility from a supervisor, respondents most often cited that they had experienced supervisors paying little attention to their opinions/statements (62%), doubting their judgment over a matter for which they were responsible (56%), putting them down or acting condescending toward them (47%), and ignoring or excluding them from professional camaraderie (44%). Additionally, respondents most commonly indicated they had experienced coworker incivility in the form of their paying little attention to their opinions/statements (45%). These results show that it’s imperative for finance and accounting organizations to develop mechanisms to address these specific concerns in striving to mitigate workplace incivility.

To gain more insight into the impact of incivility on overall job satisfaction and turnover intent, the survey asked respondents to rate their overall satisfaction with their current job and whether they plan to seek new employment within the next year. A regression analysis indicates supervisor incivility significantly correlated to an employee’s overall job satisfaction and their intent to seek new job opportunities. Of those who have experienced supervisor incivility, 24% indicated that they plan to leave their current employer within one year compared to only 6% of those that had never experienced such incivility. In addition, those suffering from supervisor incivility indicated they experienced lower overall job satisfaction.

On a scale of 0 to 8 (0 being low satisfaction and 8 being high satisfaction), those who had experienced workplace incivility rated their job satisfaction lower compared to those who never experienced incivility (4.2 compared to 6.4). While coworker incivility may not have the same level of impact on employees’ job satisfaction or turnover intent as supervisor incivility in this study, it’s important to note other recent studies have shown that coworker incivility impacts job performance. As Porath and Pearson’s research found, not only do employees who experience incivility reduce their efforts at work, but those employees that witnessed these acts also “felt less respect for and commitment to their organizations” (Mastering Civility, 2016).

Reduced job performance and loss of commitment by someone who’s experienced incivility can have a negative ripple effect across an organization. Low morale could ensue as other employees work to pick up the slack left by the poorly performing professional. If supervisors fail to address the issues, then staff conflict with company leadership could develop. As team morale drops, client service quality could suffer, impacting current client relations, future business development, and the potential for attracting new clients. Finally, as employees decide to leave their position, the organization will have to endure significant time, money, and energy costs in recruiting and hiring replacements. According to the 2022 Rosenberg Survey, an annual report on the performance of U.S. accounting organizations, the “labor shortage in the accounting profession continues to have a major impact on nearly every firm.” Based on our survey results, ensuring a civil workplace for all team members is a step in the right direction to improve job satisfaction and reduce employee turnover, which, in turn, can lessen the impact of the labor shortage on companies struggling to find talent.

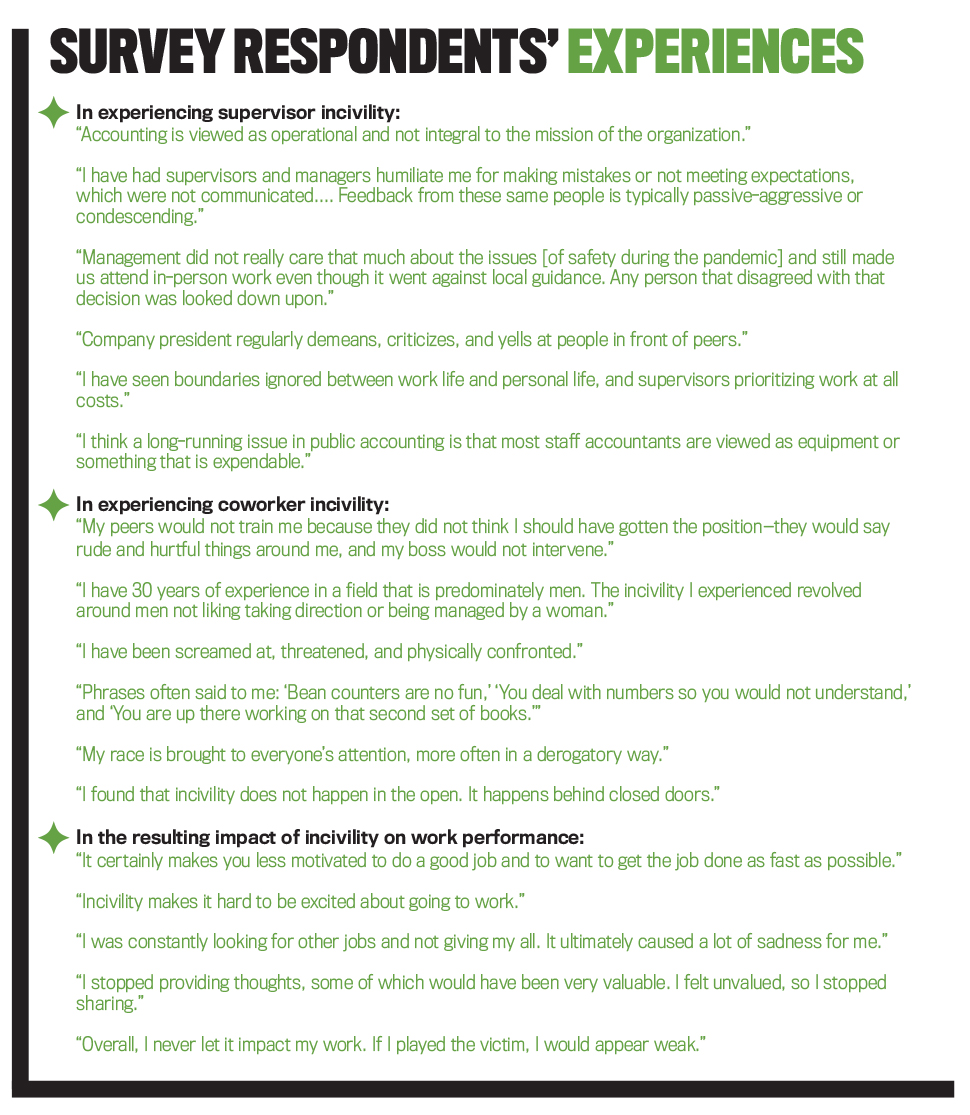

Our survey asked respondents open-ended questions to gain additional insight on the types of incivility and the resulting impact it had on their work. Hearing from those impacted by incivility, in their own words, can be eye-opening for organizations and those in leadership positions. See “Survey Respondents’ Experiences” for direct quotations from survey respondents on their experiences of supervisor incivility and coworker incivility, as well as the impact of incivility on work performance.

Our survey results show workplace incivility continues to be an issue in the finance and accounting profession, leading to higher levels of job dissatisfaction and increased likelihood of employee turnover. As such professionals become less committed to their organization, they could begin to exhibit decreased productivity and poor job performance, causing the quality of client services provided to suffer. Additionally, other company employees may need to work harder to fill these productivity gaps, decreasing team morale and increasing job stress and workload, which studies show can lead to job burnout in financial professionals. This means that even company clients and employees who have not directly experienced incivility may also be negatively impacted by its consequences. This cycle could prove detrimental to afflicted organizations. Therefore, it’s critical for finance and accounting organizations to look for ways to build a civil culture within the workplace.

RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION

Organizations should instill recruitment and retention policies conducive to a civil workplace. Setting expectations for civility starts with the interview process—interviewers have the opportunity to explicitly articulate the organization’s values and the required attributes for the position and assess the candidate’s cultural fit with the organization (Porath, “Make Civility the Norm on Your Team,” Harvard Business Review, January 2, 2018).

Including behavioral and situational questions as part of the interview process can help in evaluating whether the candidate will be comfortable at the organization (Rebecca Knight, “How to Conduct an Effective Job Interview,” Harvard Business Review, January 23, 2015). Furthermore, when employees leave the organization, human resources managers can conduct exit interviews to determine if workplace incivility is to blame for the departure (Dori Meinert, “How to Create a Culture of Civility,” HR Magazine, March 20, 2017). This will allow company leaders to further address the issue.

PUT IT IN THE HANDBOOK

Organizations need to promote peer collegiality through the development of corporate policies that discourage uncivil behavior among coworkers and peer-training and civility seminars focusing on team building and peer conflict resolution strategies (Rajashi Ghosh, Thomas G. Reio, and Hyejin Bang, “Reducing turnover intent: supervisor and co-worker incivility and socialization-related learning,” Human Resource Development International, April 2013). Mission statements and policy manuals must clearly state expectations for workplace behavior and civility (Lilia M. Cortina, Dana Kabat-Farr, Emily A. Leskinen, Marisela Huerta, and Vicki J. Magley, “Selective Incivility as Modern Discrimination in Organizations: Evidence and Impact,” Journal of Management, September 2013).

According to Porath, developing a code of civility helps to define civility for employees and reinforces civility expectations. Cortina, et al., further suggested that employees should receive training regarding civility expectations and interpersonal skills. Porath notes that civility trainings teach employees what both civility and incivility look like, provide tips on self-conduct in uncivil situations, and allow opportunities to practice civil behavior in challenging scenarios. Furthermore, organizations should put in place a consistent rewards and sanctions system to promote civil behaviors among employees.

SETTING THE EXAMPLE

Company leaders need to model civil behaviors for their employees (Thomas G. Reio Jr., “Supervisor and Coworker Incivility: Testing the Work Frustration-Aggression Model,” Advances in Developing Human Resources, February 2011). Ghosh, et al., stated that establishing a good tone at the top has been shown to help to prevent unethical behaviors, so organizations should implement leadership development programs that train supervisors on effective leadership etiquette and identification of factors that could lead to uncivil acts among employees.

These programs, they further suggested, can focus on diversity awareness, anger management, conflict management, and employee coaching and mentoring, which will allow supervisors to develop more collegial relationships with their subordinates. Furthermore, according to Ghosh, et al., it’s beneficial for organizations to reward supervisors for fostering supportive behaviors and establish zero-tolerance policies for those who continue to engage in uncivil acts.

CYBERBULLYING RISKS

With the expansion of information and communications technology in the workplace, especially with the growth of the remote work environment brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations need to pay special attention to employee technology-supported activities. Uncivil interactions and workplace cyberbullying via email, text and instant messaging, and social networking sites can be just as, if not more, harmful as those face-to-face (Vivian K.G. Lim and Thompson S.H. Teo, “Mind your E-manners: Impact of cyber incivility on employees’ work attitude and behavior,” Information & Management, December 2009; Halit Keskin, Ali Ekber Akgun, Hayat Ayar, and Şaziye Serda Kayman, “Cyberbullying Victimization, Counterproductive Work Behaviours and Emotional Intelligence at Workplace,” Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences, November 2016). According to Reio, workshops encompassing emotional intelligence training and development of civil written communication skills can help to guide such behaviors in a positive direction.

Incivility in society is now omnipresent. While workplace incivility may not be as prevalent as that witnessed outside of the workplace, it should still be of great concern to finance and accounting organizations and leaders. The workplace should be a place of civil interactions, where all are respected and ideas can flourish. As such, it’s essential that finance and accounting organizations implement techniques to successfully enhance civility in the workplace, promoting job satisfaction and, in turn, organizational commitment.

In the end, civility begins with the individual. Take a moment and evaluate your own workplace civility. Think about your actions over the last year. Did you text or email while having a conversation with a coworker or employee? Or maybe you ignored the input of others during a project? Did you ever take credit for ideas that weren’t your own or blame others for failures to which you contributed? All of these contribute to incivility. To understand areas where you may be contributing to incivility, take a full workplace incivility assessment.

March 2023