Few would likely disagree that the position most tied to strategy execution within an organization is the CFO. While the CEO, chief strategy officer (CSO), and chief operating officer (COO) are close contenders, the CFO’s role is uniquely linked to execution across all divisions and initiatives. As a result, CFOs are more in tune with business fluctuations and better equipped to find ways to bridge the strategy execution gap.

But with the ever-evolving and critical role of the CFO in strategy execution, are there better ways for CFOs to juggle these responsibilities? How might CFOs optimize their approaches to strategy execution to avoid micromanaging yet ensure sufficient oversight?

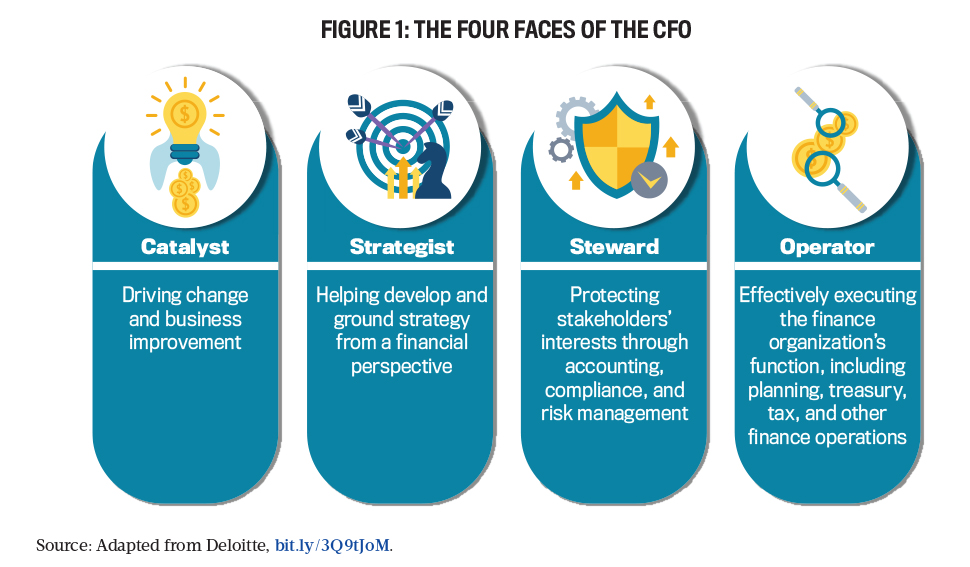

It’s now well understood that the role of the CFO has evolved. To better articulate these changes, Deloitte generated a framework that identifies the four faces of the CFO: catalyst, strategist, steward, and operator (see Figure 1).

The CFO must now effectively fulfill the historic role of controller while simultaneously acting as the catalyst of progress. Strategy execution therefore becomes one of the key considerations of the CFO, with responsibilities including:

- Greenlighting new initiatives and purchases, including digital transformation;

- Monitoring progress and returns across initiatives and purchases;

- Partnering across divisions to bridge finance and operational targets;

- Budgeting and dynamically allocating capital to the highest value initiatives;

- Preserving control over execution, solving problems, and protecting stakeholders’ interests;

- Detecting and resolving threats before they escalate; and

- Collaborating in the optimization of strategy execution to increase efficiency and reduce costs.

BALANCING CONTROL AND PROGRESS

With all those responsibilities, CFOs face a key challenge in strategy execution: the balancing act between control and progress. If sufficient consideration hasn’t been placed on how to better balance these two priorities, CFOs may find themselves on either end of the spectrum. On one hand, too much oversight and micromanagement can impede change and business improvement. On the other hand, too little can put the entire business at risk.

Too much oversight. Acting in their historic role as steward and protector of stakeholders’ interests, CFOs naturally bring a more cautionary approach to strategy execution than their executive peers. Internal changemakers and department leaders are often concerned with improving the business through specific and functional objectives. If given the opportunity, this can lead to greater risk appetite and a limitless demand for resources. The CFO in contrast must both manage risk and deploy resources appropriately across all functions and initiatives. This balancing act is one factor that can lead to too much oversight in strategy execution.

The unique capabilities of the CFO can also lead to micromanagement. The CFO is the person most grounded in the critical metrics of the organization. As business partner for each function leader, the CFO maintains a company-wide perspective. This means that the CFO has broad and deep insight regarding the inner workings of the organization, in addition to how everything comes together to create the bigger picture. Along with addressing the historic priority as controller, the capability of the CFO is often needed when it comes to aspects of execution such as decision making and problem solving.

Too little oversight. With ever-increasing responsibilities to manage, CFOs can find themselves in a position where they have less oversight than desired. This may occur from a conscious decision to liberalize their control function to enable risk taking, change, speed, and innovation. We saw this most recently as businesses were required to change and adapt quickly to new technologies and ways of work due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Too little oversight can also occur organically. Juggling multiple responsibilities and delivering insights of both breadth and depth across the organization means problems can easily slip through the cracks. Data leaks, financial scandals, and an increased chance of stagnating or failed initiatives can result.

Striking the balance. The balance between too much or too little oversight can be achieved through adopting the best practices of strategy execution. For example, tracking progress across multiple initiatives can be better managed with a connected data stack and the adoption of goal management methods, such as the objectives and key results (OKR) framework. A culture of transparency and trust, as opposed to control and compliance, can empower team members on the ground to solve problems before they escalate. And better alignment across the organization, both vertically and horizontally, reduces wasted efforts from duplicated or unaligned work.

GREATER ALIGNMENT THROUGH OKR

When thinking about strategy execution, it’s typical to think in terms of specific approaches. It’s clear, however, that there’s a need to rethink the “engine” that powers strategy execution—the operating model. Factors such as the lingering strategy execution gap, increased business velocity and disruption, and the wealth of data available suggest that a “modern operating model” is required to optimize strategy execution—specifically, an operating model that enables achievement of goals and outcomes faster and more effectively, in addition to navigating the threats and opportunities of a rapidly changing world.

OKR is a goal management method adopted by leading companies such as Google and Adobe. The method uses objectives as a better way to define and organize goals. Objectives are qualitative in nature—they must describe what you want to achieve, be inspirational, stretch your team’s capabilities, and have a deadline, among other things. Key results are individual elements that “metrically” quantify whether you have achieved your objectives and serve to track progress along the way. Here’s a quick OKR example:

- Objective: Build an all-star finance team.

- Key result 1: Hire five high-performing team members.

- Key result 2: Every finance team member completes 30 hours of professional development.

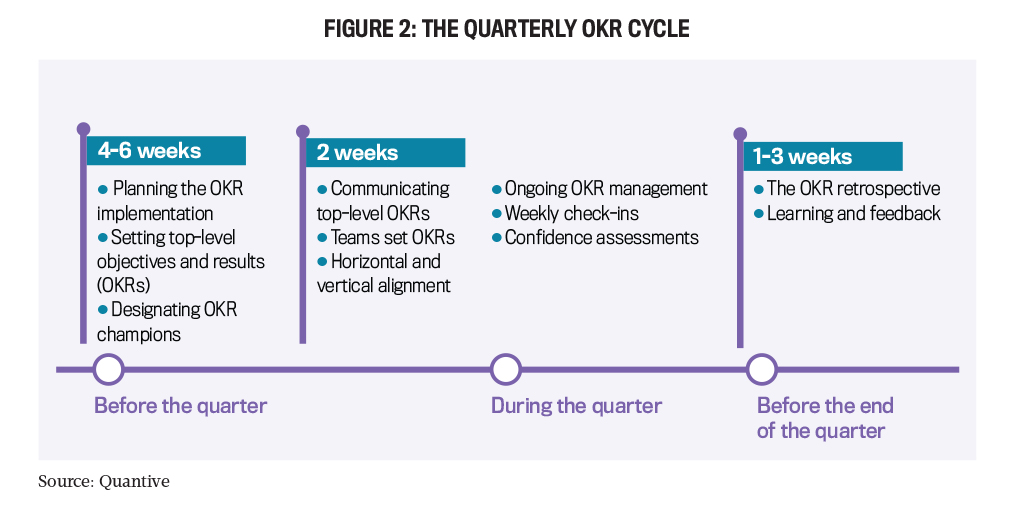

OKR typically functions around quarterly cycles, but annual and alternative cycles (such as six-week) may be used depending on the needs of a team or organization. OKR cycles are a core part of the methodology, as emphasis is placed on learning feedback loops and adjusting course based on collected data. Figure 2 provides an overview of what a quarterly OKR cycle looks like.

OKR is meant to be applied across an entire organization, with the overall goal to better connect strategic imperatives to execution realities. There are numerous benefits to OKR, but the most important is greater alignment. Often, the executive level generates excellent strategies that fail due to incorrect, ineffective, or unaligned implementation. In fact, faltering strategy execution is the top risk identified by CFOs, according to Deloitte.

There are many contributing factors, but one of the most critical is often lack of alignment. Research from Gartner highlights that as much as 67% of integral functions aren’t aligned with corporate strategy (Jackie Wiles, “The 5 Pillars of Strategy Execution.”

So how do OKR and greater alignment benefit the CFO’s priorities?

Vertical alignment. Top-down, or hierarchal, alignment describes how well the strategic thinking of the executive level is communicated and executed throughout the organization. This alignment should ideally extend to the far edges of the organization—right down to the most junior employees.

When applied correctly, OKR enables vertical alignment through greater clarity and transparency of strategic objectives. This ensures that the entire organization works toward mission-critical objectives, which reduces wasted work and the costs from misguided initiatives. It also increases efficiency gains at the local level by acting as a north star for decision making—for instance, when deciding which technology purchases are necessary.

Horizontal alignment. Alignment across the organization can be described as horizontal—how different functions, departments, networks, and even the broader company ecosystem work together toward company objectives. This allows for the interdependencies, capabilities, and bandwidth of the organization to be optimized in a collective, evolving way. Horizontal alignment leads to less duplication of work, better collaboration toward strategic objectives, and a more efficient organization overall.

Together, better vertical and horizontal alignment means less oversight is needed from the CFO in strategy execution. As all members of the organization can effectively connect their work to each other and the broader objectives, there’s less concern that work, initiatives, and purchases will go off track.

Board alignment. A unique benefit of OKR for the CFO is better board alignment. Short-term thinking is the standard in our modern business climate, which undoubtedly has an impact on strategy execution. Long-term initiatives are often hindered by short-term priorities. To combat this, OKR can be used in addition to other connected data to bolster support for long-term initiatives by telling a more complete story of organizational progress. In turn, there should be reduced pressure to fulfill only short-term priorities as positive business momentum with a holistic view can be presented to the board.

DETECTING AND RESOLVING THREATS

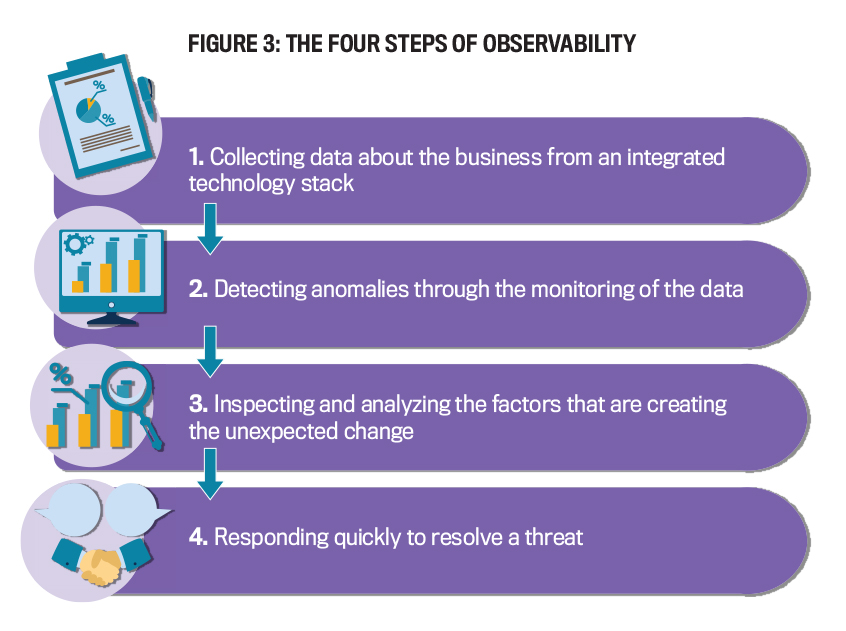

Detecting and resolving threats before they escalate is a key aspect of protecting the business and stakeholders’ interests. This can be achieved through investing in the practice and systems of business observability. This primarily involves monitoring the key performance indicators (KPIs) of the business to ensure business continuity, but it also aids decision making for process improvement, adaptability, and innovation. Observability can be summarized broadly in four steps:

1. Collecting data about the business from an integrated technology stack;

2. Detecting anomalies through the monitoring of the data;

3. Inspecting and analyzing the factors that are creating the unexpected change; and

4. Responding quickly to resolve a threat. (See Figure 3.)

Obvious examples of threats would be critical IT infrastructure going down or a cybersecurity breach. But threats can extend well beyond business systems, depending on the connectedness of your data stack and observability approach. KPIs from all aspects of the business can be collected and analyzed to detect vulnerabilities across the board. For instance, data can be analyzed regarding employee retention through software that collects engagement metrics.

Although the benefits of resolving threats for the CFO are clear, engaging in a concentrated effort to master the practice and systems of observability can greatly improve the results. For many businesses, so much data is produced each day that it’s impossible to collect and process data manually. This of course suggests that consistently identifying and resolving threats in real time is a practical impossibility. Speed is also a factor—a critical threat may be identified by a team member, but the damage may have already been done.

Modern technologies and approaches to observability solve these problems. AI-driven prescriptive analytics and connecting data from across the organization create a way for anyone in the organization to better respond to threats—ideally well before they escalate. In turn, the goal of protecting the business without too much oversight is achieved.

COMBINING OKR AND KPIs

A modern operating model is data-driven, which makes tracking the progress of OKR and the observability of KPIs critical components. Working together, this enables the creation of a more robust picture of what’s happening in the organization. This unlocks many benefits including:

- Empowered decision making using the abundance of data available. This leads to better certainty in execution regarding adjustments or opportunities to innovate.

- Monitoring and dynamically allocating resources to the most promising initiatives (see Ariel Babcock, Sarah Keohane Williamson, and Tim Koller, “How executives can help sustain value creation for the long term,” McKinsey & Co., July 22, 2021). This, in turn, reduces sunk costs in flailing or failed initiatives.

- Visibility and management of multiple initiatives. Modern organizations have a lot to contend with simultaneously. Environmental, social, and corporate governance compliance; digital transformation; and becoming more competitive are but a few examples. A data-driven system is required to better manage and optimize alignment and resources across divisions and initiatives.

CREATING A RESILIENT ORGANIZATION

An ideal end state for the CFO’s priorities in strategy execution would be for the company to evolve into a resilient organization. This refers to the ability of an organization to withstand shocks and crises. Taken one step further, an organization with peak resilience may become anti-fragile, which is a concept developed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb that describes the ability to not only endure shocks and crises but become stronger in response. Crises can be internal, such as the loss of critical personnel, or external, such as supply chain disruptions. Crises may also vary in timelines, from abrupt events to lingering challenges like a shrinking pipeline of opportunities.

An organization with a strong market position will naturally have a level of resilience due to its position. Large cash reserves, brand equity, and strong relationships will always play a role in responding to crises. But a strong market position alone isn’t enough to be resilient, as evidenced by major retailers filing for bankruptcy during the recent pandemic. To truly become resilient requires making fundamental changes to how the organization works. This means looking at components of the operating model such as company structure, culture, and the overall guiding principles of strategy execution.

Embracing constant transformation. As resilience occurs in response to changes, adaptiveness and evolution must be a feature of the operating model. Change should be baked into the DNA of the company, as opposed to reacting solely to specific events or challenges. One way to enable this is through creating a culture of organizational learning. The creation of knowledge, insights, and wisdom shouldn’t be limited to only academic institutions. Businesses increasingly need to be at the forefront of knowledge, both in their domain and the broader world, in order to adapt and grow.

The starting point to actualize this requires collecting raw data and information. KPIs from a connected data stack and the information provided from OKR tracking and retrospectives are great mechanisms for this purpose. Thereafter a combination of AI and human analysis can produce knowledge, insights, and wisdom to change, improve, and adapt the organization. The embedded system and culture of learning contribute to a constantly evolving organization that can better survive a fast-changing world.

To better enable change, revisiting organizational structure is also key. It’s time to reevaluate traditional approaches to work to foster greater flexibility and responsiveness to change. Teams and individuals shouldn’t be confined to one project, initiative, or even department, but instead be dynamically deployed across the organization as needed. New ways of work, including hybrid work and the flexible workforce (gig workers and freelancers) can also better support constant transformation.

Empower the workforce. Shocks, crises, and a rapidly changing world mean there’s no longer time to go up and down the chain of command for decision making. An organization can never truly be resilient unless the individuals within are empowered to act to resolve situations before they escalate to the point of peril. In addition, they should have the capacity to innovate and incrementally improve the organization, even at the furthest edge of the network. One possible route to enact this is through adopting an operating model that allows a distributed (as opposed to hierarchal) power structure.

This may not have been possible in the past, but the abundance of data now available creates an opportunity to empower the teams and individuals closer to the challenges at hand to make decisions. This enables greater speed since there’s no longer a need to deal with layers of bureaucracy. More accurate and reliable decisions can also be made as people armed with the details of execution are more likely to have the right answer to issues. Combined with greater alignment to strategic objectives, employees will be in a strong position to act autonomously to improve the organization without extra oversight.

Of course, the approach described here relies on a completely new paradigm of leadership—from control and compliance to trust and empowerment. Transitioning to this new way of thinking can be difficult, but the benefits of doing so mean greater resilience, optimization across the organization, and less oversight needed from the CFO.

Overall, the role of the CFO in today’s business world requires adopting best practices for strategy execution. The key challenge of balancing the traditional role of control, with the emerging role of the catalyst of progress, can be best managed through approaches such as building alignment, observability, and creating a resilient organization. Through modern approaches to strategy execution, CFOs can reduce the oversight needed across all parts of the business—all the while ensuring risk is managed, progress toward objectives is made, and the organization is continuously improving.

February 2023