SPAC BASICS

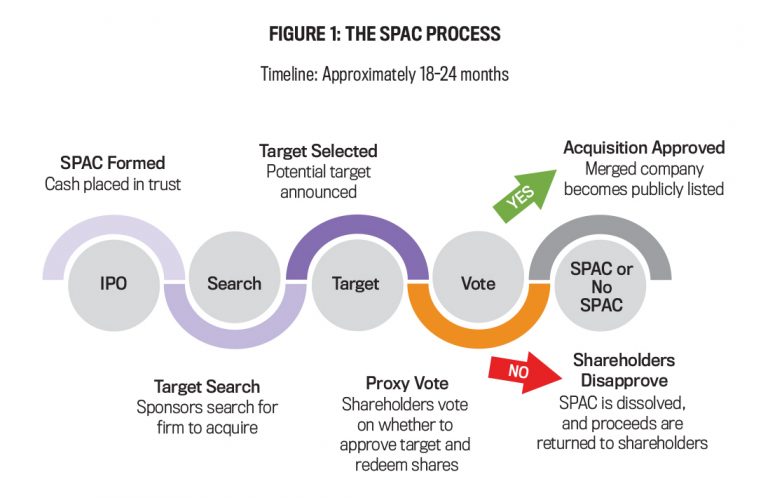

A SPAC is a shell company established and listed on a public stock exchange for the sole purpose of raising cash to merge with one or more private companies without going through the costly and lengthy traditional IPO process. SPACs are often called “blank check” companies because investors are providing funding with the intent of investing in a particular arena, for example, gaming, but not necessarily in a known entity. A unique feature of a SPAC is that it isn’t an operating business. The SPAC is simply a pool of capital intended to fund the purchase of an operating business. The initial SPAC investors have typically been institutional investors, including private equity and hedge funds, but also individuals. A SPAC is set up by a management team called sponsors, who raise money from investors in an IPO by issuing “units,” typically at a price of $10. Investors buy the units, which consist of a share and a fraction of a warrant. The warrant is an option issued by the company that allows the holder to buy a share at a stated price, often $11.50, after the completion of the merger. Warrants were an important component in the SPAC boom since investors can profit after the deal if the share price rises and they exercise the warrants to buy more shares at a low price. The number of warrants included in a unit varies by SPAC. In most SPACs, the sponsors get a stake of approximately 20% in the SPAC for a very low price and can purchase additional warrants. The sponsor makes money if a merger occurs and the new company succeeds. After identifying a target, the SPAC then merges with the target company in a process often called de-SPACing. Since the SPAC is already a public company when it merges with the target company, the reporting requirements are far less onerous than if the target company were to go through an IPO. The SPAC must file with the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), but the filings are much simpler than traditional IPO filings. SPACs have a set timeline to make an acquisition, usually two years (see Figure 1). If the SPAC sponsors can’t identify a potential target company, then shareholder funds are returned. When the SPAC announces the formal target, the SEC reviews the terms. The next step is a proxy vote. Investors who don’t agree with the business target can exit and liquidate their shares to recover the initial investment plus accrued interest. If enough shareholders approve the acquisition, it goes through as long as the consenting investors are above the threshold set in the proxy. The benefits to a private company may include fast access to public equity markets through a process that’s simpler and less regulated than the typical IPO. Company owners can retain some equity ownership and may also gain access to knowledge and competencies from the SPAC sponsors.

For early-stage companies that haven’t yet generated positive cash flows or significant revenues, SPACs can provide founders an essential avenue to new capital. For more mature companies, SPAC proceeds can fund growth and acquisitions. The sponsors often secure additional funding through private investment in public company (PIPE) commitments. SPACs also provide public equity capital access to small and medium-sized companies that haven’t enjoyed such access in the past.

The benefits to a private company may include fast access to public equity markets through a process that’s simpler and less regulated than the typical IPO. Company owners can retain some equity ownership and may also gain access to knowledge and competencies from the SPAC sponsors.

For early-stage companies that haven’t yet generated positive cash flows or significant revenues, SPACs can provide founders an essential avenue to new capital. For more mature companies, SPAC proceeds can fund growth and acquisitions. The sponsors often secure additional funding through private investment in public company (PIPE) commitments. SPACs also provide public equity capital access to small and medium-sized companies that haven’t enjoyed such access in the past.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

FACTORS TO CONSIDER

While SPACs can provide another avenue to access public equity, they face complex valuation issues and risk of personal liability for their sponsors and board of directors. Accounting and finance professionals need to understand the related risks as well as regulatory, reporting, and compliance requirements. And companies considering a SPAC need to be aware of both the benefits and risks associated with a SPAC vehicle and any related regulations. Considerations include:

Fast exit: For entrepreneurs considering exit strategies, SPACs provide a fast and viable alternative to an IPO or a sale to a strategic or financial buyer. Speed can be a benefit if there’s urgency or concern regarding market volatility, but management must consider if the timeline is feasible.

Valuation certainty: In a SPAC, the target company negotiates a fixed price per share, removing some of the valuation uncertainty inherent in the IPO process where market conditions change, information arises, and valuations fluctuate widely prior to setting the IPO price.

Sponsor quality: Sponsor experience in the industry and a successful track record in capital raising and deal execution are essential. Some SPACs provide experienced management teams who can add value during and after the merger.

Cost: Depending on the sponsor ownership, the deal may ultimately be more costly than an IPO in terms of equity dilution to target shareholders.

No breakup fees: Unlike most public merger or acquisition offers, SPACs typically don’t include a breakup fee.

Management and board readiness: The SPAC timeline is short, so the management team and board must be prepared for the process including reporting; compliance; environmental, social, and governance concerns; and other considerations.

Accounting and finance expertise: Because a SPAC is a shell company with no operations, it doesn’t have accounting and finance teams in-house. Thus, a gap can often exist between the capabilities of your organization and the SPAC. The internal teams may not have the expertise needed to navigate the process, the nuanced paperwork requirements, or other strategic considerations that are unique to being acquired by a SPAC.

Complexity in required filings: Even though SPACs are considered to have less onerous reporting requirements compared to IPOs or typical mergers and acquisitions, there are required SEC filings—and those continue to expand. If the necessary paperwork isn’t completed or is submitted incorrectly, companies can encounter regulatory snags that would stall the deal and distract executives from key business initiatives.

Post-deal risks: Depending on your company, there may be additional SPAC risks that emerge following a closed deal. For example, private equity-backed companies have unique considerations in the sense that a sale to a SPAC won’t constitute a “complete” exit. This can create some nuance as early investors, known as general partners, look to maximize their returns through secondary sales following the merger.

Changing regulations: On March 30, 2022, the SEC issued a proposed rule to enhance investor protection between SPACs and private operating companies. The objective of these proposed regulations is to more closely align the financial reporting requirements of business combinations with those of a traditional IPO. The proposal includes:

- The financial statements of the target company must be audited in accordance with Public Company Accounting Oversight Board standards.

- The financial statement time-period requirement in which the target company may report two years of financial statements would be expanded to three years.

- The age of the financial statements provided by a target company would depend on whether the target company qualifies as a smaller reporting company.

- Existing financial reporting practices would be codified by requiring the target company to apply Regulation S-X, Rule 3-05, or Rule 8-04 (or Rule 3-14) for real estate, to an acquired or to-be-acquired business.

- Existing financial statement requirements would be codified by allowing the registrant to omit the pre-combination financial statement of the SPAC once such financial statements have been filed for all required periods through the acquisition date.

In addition, the proposal includes enhanced disclosure requirements as well as additional protections for SPAC IPOs and de-SPACing transactions.

In addition, the proposal includes enhanced disclosure requirements as well as additional protections for SPAC IPOs and de-SPACing transactions.

A HISTORY OF EBBS AND FLOWS

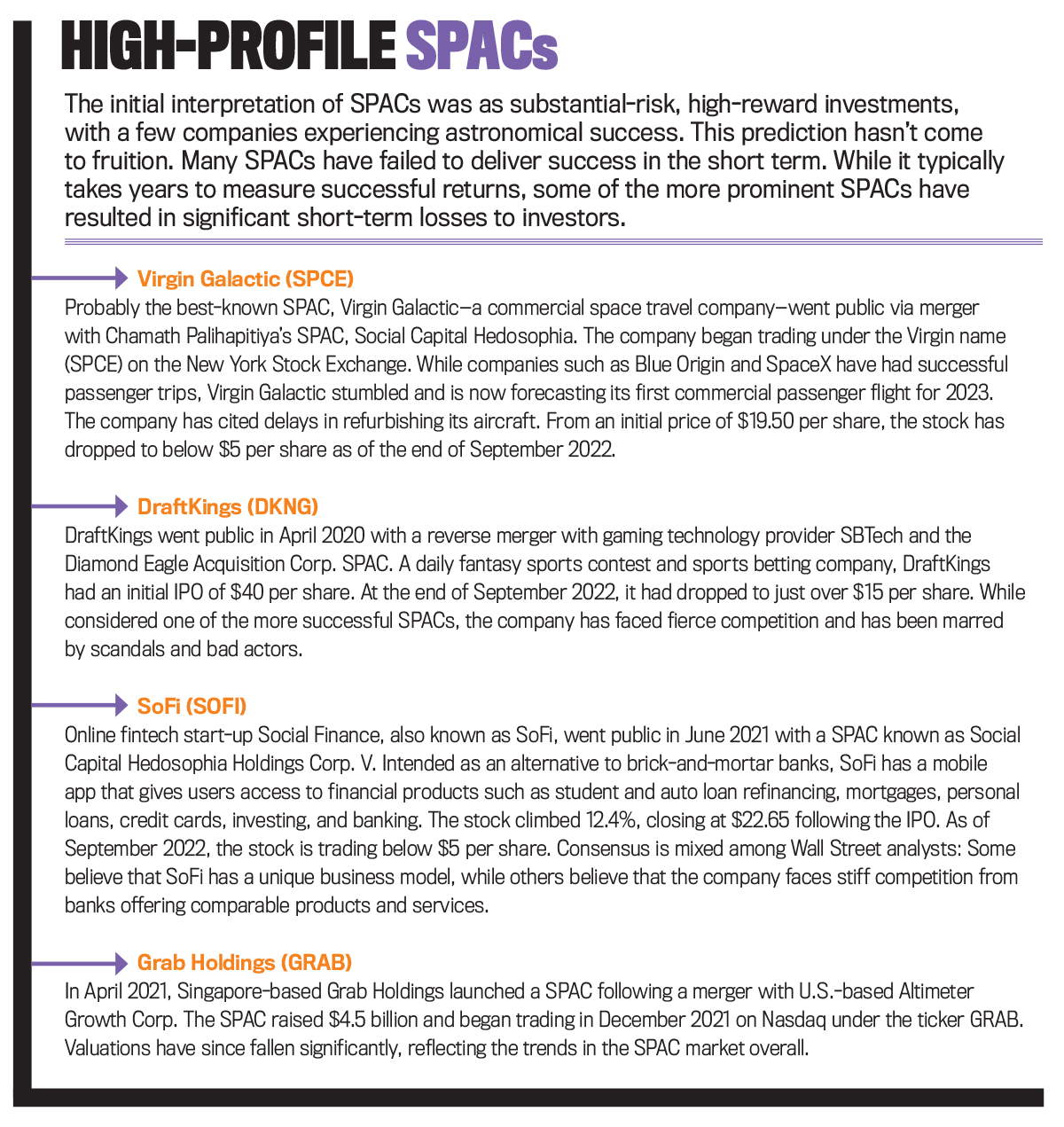

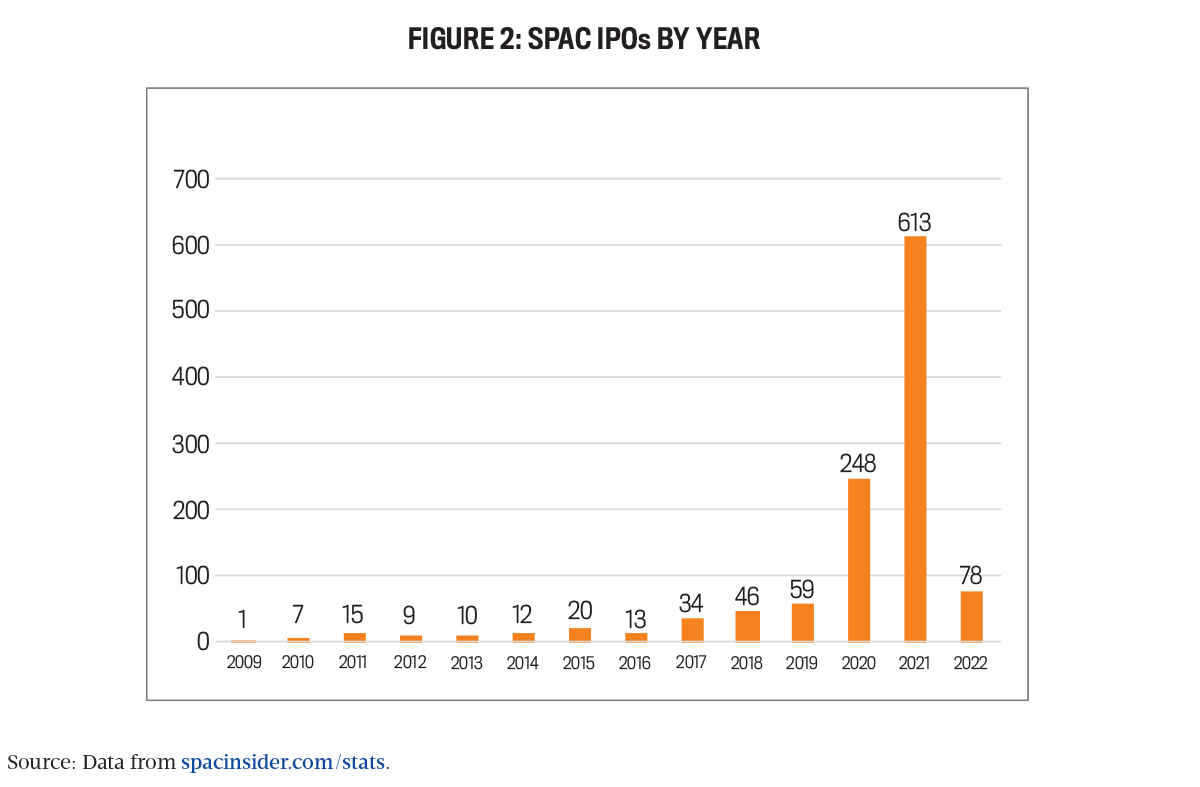

Market conditions and regulatory issues could further influence whether a SPAC deal is the right decision for a company. The history of SPACs shows how their use and appeal has fluctuated. While the recent flurry of activity elevated SPACs to greater awareness beyond financial circles, a version of SPACs has been around since at least the 1980s when so-called “blank check” companies in the United States raised funds—mostly in the penny stock market—for shell corporations with the stated purpose of merging with an unidentified private company. These companies led to widespread “pump and dump” fraud in which rumors of an impending merger would pump up stock prices and then insiders would sell shares before retail investors learned the truth. Eventually laws passed by the U.S. Congress and regulations enacted by the SEC provided some investor protection by mandating enhanced disclosures and requiring that the SPAC proceeds remain in escrow accounts until the merger is completed. Fast-forward to the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s, when the “blank check” investment vehicle was redesigned and reemerged with the SPAC name. While SPAC volume declined following the dotcom bust and new regulations in the early 2000s, SPACs didn’t go away completely. In 2007, 65 SPACs were completed, raising $11 billion in proceeds. Included in that group was the Endeavor Acquisition Corp. buyout of American Apparel, which led to the December 2007 New York Times headline “Wall Street’s New Status Symbol: the SPAC.” But SPAC volume again diminished significantly during the financial crisis of 2008-2009. By 2019, SPAC volume was rising (see Figure 2) as the perceived quality of SPACs improved based on experienced management teams working with well-known sponsors to raise capital for higher-quality companies. Some also attribute the COVID-19 pandemic with increasing investor appetite since retail investors suddenly stuck at home with few outlets on which to spend their time or money jumped into SPAC investing (David Benoit, “SPACs Rescued Wall Street From the Covid Doldrums,” The Wall Street Journal, January 22, 2021).

Small investors historically were unable to access the IPO market, so SPACs provided new opportunities. At the same time, cash-strapped companies struggling during the pandemic could use SPACs for quick cash infusions. Other companies became concerned that market volatility would derail their IPO plans if valuations fell, so the speed of the SPAC process was an attractive feature. Debt markets also played a role, making additional back-up financing cheaper and more readily available.

Hedge funds have been huge players in the SPAC market, viewing the investments as having little downside while providing equity upside. A hedge fund could put cash in a SPAC and accrue interest until the deal was announced. At that point, the hedge fund could opt to stay in if optimistic about the new company’s prospects or redeem its shares—with interest—if it wasn’t interested in staying on after the merger.

Even if the shares were redeemed, the warrants issued with the SPAC units could be held or sold because they trade separately. Once a SPAC merges with its target, the warrants convert to relatively inexpensive stakes in the new company, which provides warrant holders the ability to profit from the merger even if the original shares had been redeemed.

By July 2020, SPACs seemed to have gone mainstream. Pershing Square Capital Management, led by billionaire investor Bill Ackman, was working with Citigroup to create a SPAC, while Jefferies Financial Group and UBS raised $4 billion in the largest-ever SPAC IPO.

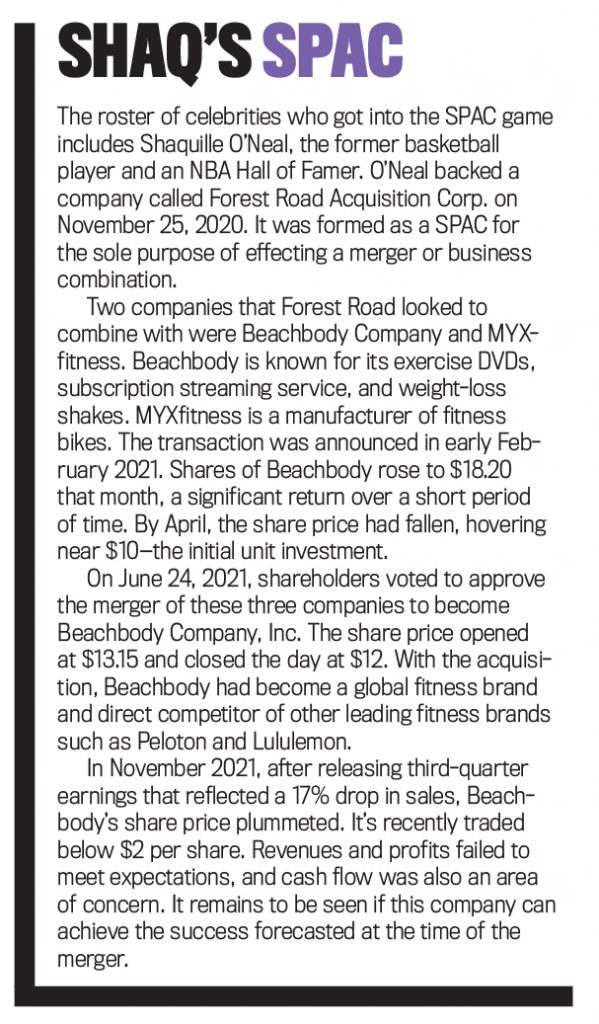

Even celebrities were getting into SPACs, with Shaquille O’Neal, Alex Rodriguez, Martha Stewart, and Serena Williams signing on to SPACs as sponsors or in leadership roles focused on promoting a SPAC to potential investors. The list of celebrity endorsements grew to the point that the SEC issued an investor alert in March 2021 that included the warning, “It is never a good idea to invest in a SPAC just because someone famous sponsors or invests in it or says it is a good investment.” (See “Shaq’s SPAC” for more on O’Neal’s SPAC investment.)

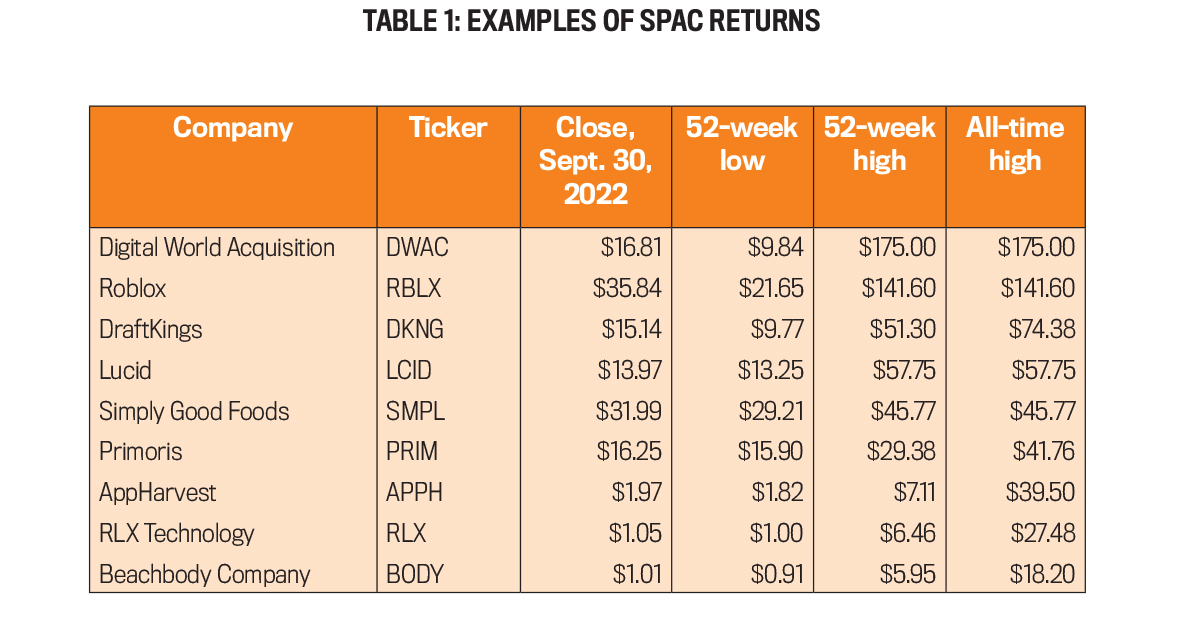

Yet the hype wouldn’t last. By the summer of 2022, investor appetite had disappeared. On July 26, 2022, Ackman announced his decision to redeem all outstanding shares of his SPAC, saying he couldn’t find a suitable or executable transaction. Evidence mounted that SPAC performance had been poor for investors and that any significant returns were earned by the sponsors (see Table 1). Increased regulatory scrutiny and declining valuations also combined to further reduce SPAC attractiveness. As of mid-September 2022, SPAC Analytics cited 547 SPACs with $145 billion in proceeds seeking acquisition, with little time left in the 24-month merger window to complete deals.

Small investors historically were unable to access the IPO market, so SPACs provided new opportunities. At the same time, cash-strapped companies struggling during the pandemic could use SPACs for quick cash infusions. Other companies became concerned that market volatility would derail their IPO plans if valuations fell, so the speed of the SPAC process was an attractive feature. Debt markets also played a role, making additional back-up financing cheaper and more readily available.

Hedge funds have been huge players in the SPAC market, viewing the investments as having little downside while providing equity upside. A hedge fund could put cash in a SPAC and accrue interest until the deal was announced. At that point, the hedge fund could opt to stay in if optimistic about the new company’s prospects or redeem its shares—with interest—if it wasn’t interested in staying on after the merger.

Even if the shares were redeemed, the warrants issued with the SPAC units could be held or sold because they trade separately. Once a SPAC merges with its target, the warrants convert to relatively inexpensive stakes in the new company, which provides warrant holders the ability to profit from the merger even if the original shares had been redeemed.

By July 2020, SPACs seemed to have gone mainstream. Pershing Square Capital Management, led by billionaire investor Bill Ackman, was working with Citigroup to create a SPAC, while Jefferies Financial Group and UBS raised $4 billion in the largest-ever SPAC IPO.

Even celebrities were getting into SPACs, with Shaquille O’Neal, Alex Rodriguez, Martha Stewart, and Serena Williams signing on to SPACs as sponsors or in leadership roles focused on promoting a SPAC to potential investors. The list of celebrity endorsements grew to the point that the SEC issued an investor alert in March 2021 that included the warning, “It is never a good idea to invest in a SPAC just because someone famous sponsors or invests in it or says it is a good investment.” (See “Shaq’s SPAC” for more on O’Neal’s SPAC investment.)

Yet the hype wouldn’t last. By the summer of 2022, investor appetite had disappeared. On July 26, 2022, Ackman announced his decision to redeem all outstanding shares of his SPAC, saying he couldn’t find a suitable or executable transaction. Evidence mounted that SPAC performance had been poor for investors and that any significant returns were earned by the sponsors (see Table 1). Increased regulatory scrutiny and declining valuations also combined to further reduce SPAC attractiveness. As of mid-September 2022, SPAC Analytics cited 547 SPACs with $145 billion in proceeds seeking acquisition, with little time left in the 24-month merger window to complete deals.

WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD?

Will the recent poor performance and additional regulation put an end to SPACs? While some believe SPACS have flamed out due to poor performance and increased regulation, SPACs do provide potential advantages to companies and investors. The emergence of well-known private equity firms becoming SPAC sponsors will likely continue as these firms expand access to equity capital beyond traditional sources. Even now, SPAC activity continues in the U.S. and globally. In September 2022, U.S.-based Intuitive Machines announced a SPAC with a valuation of near $1 billion. SPACs have also become popular in Europe recently, with global law firm White & Case reporting that European Union SPACs raised $1.78 billion in the first half of 2022. SPACs have also recently spread to Israel, Latin America, Hong Kong, and Singapore with a handful of deals completed in 2022. We anticipate SPACs will continue at lower volumes and may eventually regain popularity when favorable market conditions return. The structures will adjust as needed to the competitive landscape and new financial regulations. Though it’s likely that celebrity SPACs won’t become a trend again: Future investors and target firms will pay greater attention to the experience and track records of sponsors.

November 2022