Revenue management involves using various tools and techniques, including strategic pricing, trend analysis, distribution channel analysis, and costing. Advances in business intelligence technology have changed the availability of data to support revenue management decisions. Today, revenue managers increasingly use analytics to predict customer demand. They integrate that information with other data sources to make fact-based or scientific pricing decisions.

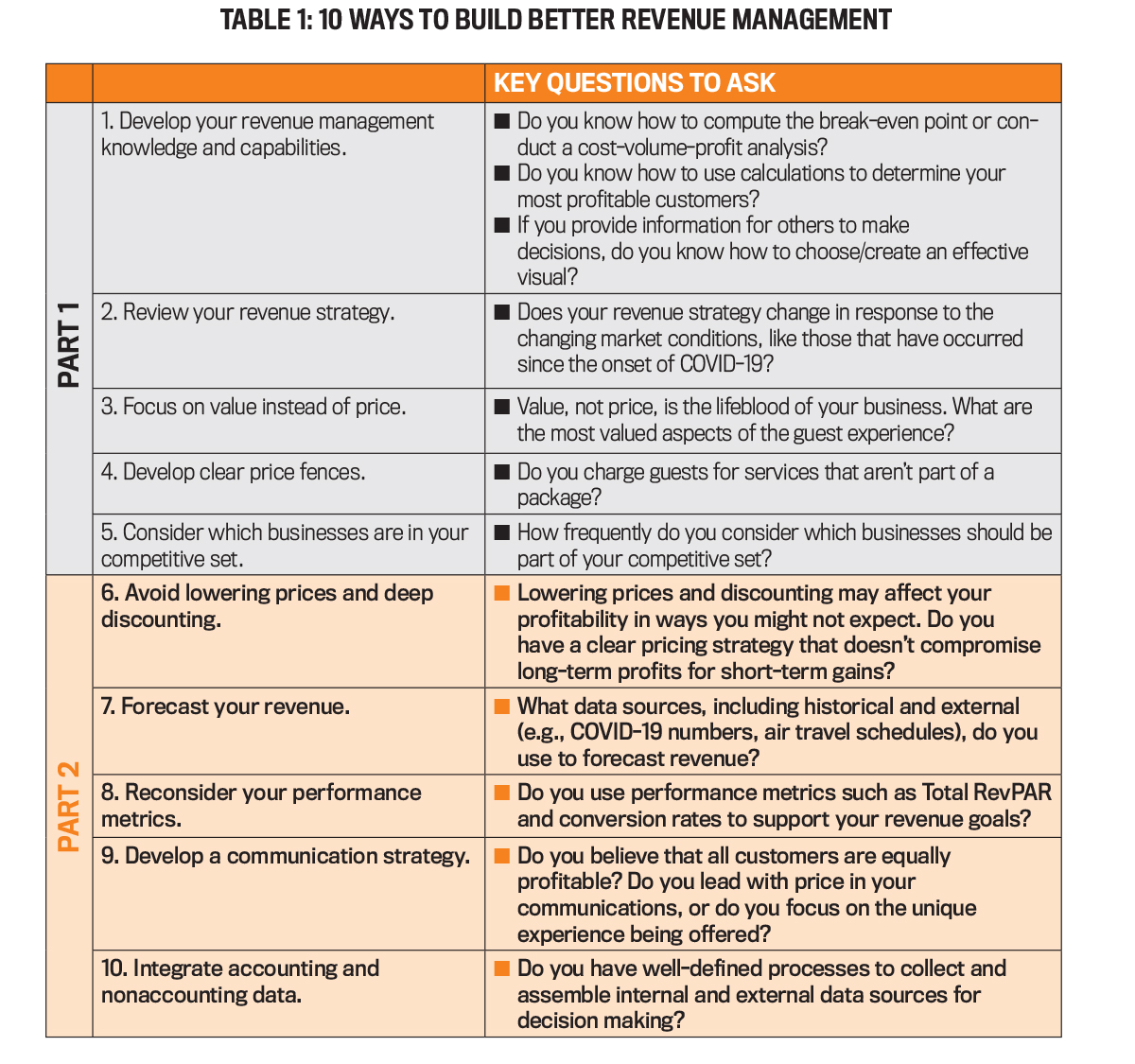

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), however, tend to lag behind in the use of revenue management practices, with managers often relying on instinct or basic one-size-fits-all strategies. But there are steps they can take to expand their revenue management capabilities and implementation. In the October 2022 issue of Strategic Finance, we discussed five of the 10 ways to build better revenue management (see Table 1) derived from our research on SMEs in the hotel industry in Queensland, Australia, during the COVID-19 pandemic (see “How We Conducted Our Study”). This month, we look at the remaining five. As noted in Part 1, these lessons might not apply to every industry, but they should be helpful for companies that operate with a fixed capacity of a perishable product.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

- Avoid lowering prices and deep discounting.

Many businesses consider lowering prices or deep discounting when faced with uncertainty. Improvements in volume may follow when businesses use deep discounting, but it also affects how the customer perceives value. Deep discounting without clear data on the customer’s willingness to pay may affect the organization’s financial performance.

Our research indicates that hotel customers changed during COVID-19 due to border closures and other measures. Hotels had little understanding or data on customers’ willingness to pay. Many smaller hotels held onto pre-pandemic assumptions—for example, that customers still preferred overseas travel—and felt that they would need a price incentive to get customers to book a room.

Other hotels held fast to their pricing policy. They kept the same or similar prices, knowing that many customers had been isolated from their community or practicing social distancing. They knew that staycations might produce psychological benefits that increase their customers’ willingness to stay and pay at a specific time.

Hotels that took the latter approach also explained that no one in the industry wins when deep discounting tactics are used. Returning to normal prices can take years when this tactic is used. In an interview, a hotel manager said:In this sort of [pandemic] time, people just panic and go, “Oh, discount. Discount’s the way. Cheaper, cheaper, cheaper, cheaper.” The golden yield rule is: Why would you discount on a low-demand period and give the small number of people that want it here a cheaper price? It makes no sense. In a low-demand period, where everybody is discounting, don’t discount. Keep your price strong, and if they want to come to you, they’ll come.

We also found that many SMEs now focus on getting repeat business. They keep databases of customer email addresses to send them the latest promotions and offers. Small hotels often prefer to send customers a reminder about the hotel’s discount if the customers book directly. SMEs tend to provide the same price to all customers and don’t seek to differentiate value among different customer groups. Because many small hotel managers remain unaware of the cost of serving customers, they’re reluctant to set prices differently for different segments of customers. In the end, they remain unaware of unprofitable customers who may still pay more if they value specific attributes of the provided service.

- Forecast your revenue.

We found that SMEs prefer simple forecasting methods that permit rapid updates to help them respond to unexpected external events. In particular, we discovered that those working in small hotels were more likely to base their forecasts on intuition and not historical data. Effective revenue management depends on forecasting demand, price sensitivity, and cancellation probabilities. Shifts in customer segmentation combined with uncertainty surrounding government measures and increases in COVID-19 cases made forecasting challenging. Hotels told us they revised their forecasts more frequently at the onset of COVID-19 as well as when lockdowns and border restrictions were established. To improve the accuracy of their forecasts, they needed to understand how long it took customers to regain confidence and rebook once lockdowns ended and if they had confidence in the government to lift the lockdown in the announced time frame. Hotels with dedicated revenue management staff collected data on booking rates each time the government introduced measures to help identify patterns in how customers react under current circumstances. When revenue managers use historical data today, they’re using data from 2019 when there were fewer external events likely to have affected booking patterns, length of stay, and particular customer segments’ willingness to pay. Historical data forecasting is relatively easy because many hotels have reservation systems that record customer transactions. Depending on the system, the data collected can be detailed and include price promotions, price fences applied, etc. Still, that data doesn’t capture outside events that may have occurred. It will show an increase or a decline in bookings, but it doesn’t provide clues as to why the change might have happened.

To improve the accuracy of forecasts, businesses need internal historical data, and they also need data about the external environment. A hotel manager commented:I think for us being so small, we really need to constantly be looking at what’s going on around us on the Gold Coast. ... Trying to monitor our surroundings constantly. And even taking things into account on more of a countrywide basis. Luckily, we haven’t had bushfires this year, but things like that will potentially impact as well. I think for us, especially, it’s changed so much.

Forecasting based on historical performance won’t account for new competitors that enter the market or new product offerings offered by competitors. For example, in Queensland’s capital city, Brisbane, several new hotels were opened in late 2019 and 2020.- Reconsider performance metrics.

Click to enlarge.

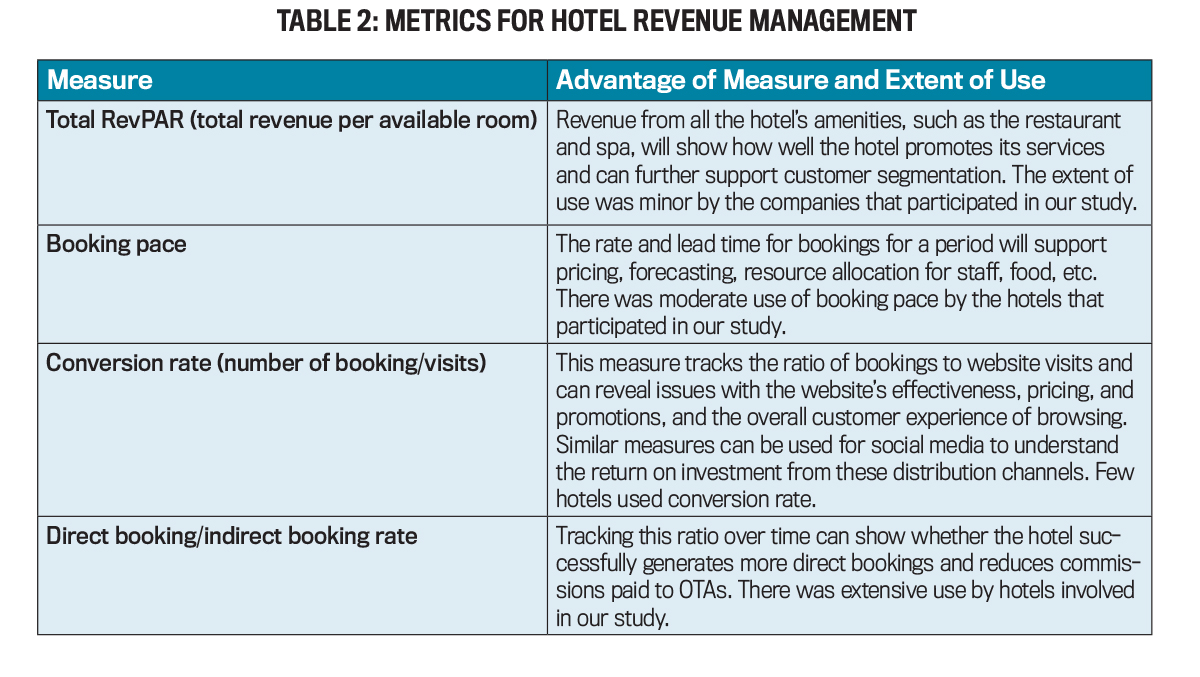

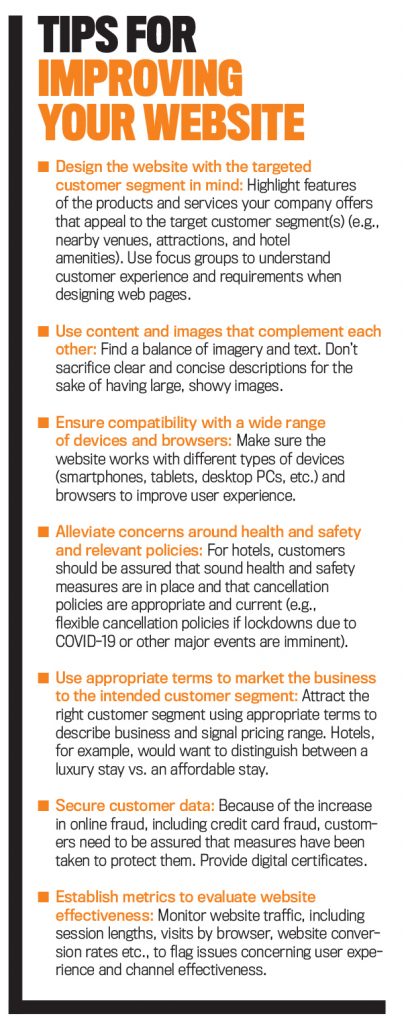

Our research on the hotel industry also shows that SMEs are trying to get customers to book with them directly because the commission they pay to online travel agencies (OTAs) can be as much as 25%. Many hotels that took part in our study had made significant investments in their websites at the onset of COVID-19. Yet few hotels in our research calculate or monitor an online channel’s effectiveness using measures such as conversion rates (number of bookings/number of visits), and many don’t use metrics such as click-through rate and costs per click to understand the return on investment of social media distribution channels.

It was apparent, however, that hotels closely followed customer booking preferences according to the different booking channels, particularly direct bookings as opposed to bookings via OTAs and other travel agencies. Revenue managers frequently commented on the percentage change in customer preferences for direct bookings vs. OTAs. They considered this a good sign of whether the investment to redesign their website effectively improved the organization’s financial performance (see “Tips for Improving Your Website”).

Click to enlarge.

Our research on the hotel industry also shows that SMEs are trying to get customers to book with them directly because the commission they pay to online travel agencies (OTAs) can be as much as 25%. Many hotels that took part in our study had made significant investments in their websites at the onset of COVID-19. Yet few hotels in our research calculate or monitor an online channel’s effectiveness using measures such as conversion rates (number of bookings/number of visits), and many don’t use metrics such as click-through rate and costs per click to understand the return on investment of social media distribution channels.

It was apparent, however, that hotels closely followed customer booking preferences according to the different booking channels, particularly direct bookings as opposed to bookings via OTAs and other travel agencies. Revenue managers frequently commented on the percentage change in customer preferences for direct bookings vs. OTAs. They considered this a good sign of whether the investment to redesign their website effectively improved the organization’s financial performance (see “Tips for Improving Your Website”).

- Develop a communication strategy.

So how do we make sure that once the border opens up and [customers] can still travel overseas, they come back to us when they want a short break? I feel like we are not doing that very well at the moment. We just go, “Great, they’re staying, let’s just bombard them with 20 more emails about our deals or what we are doing.” And that’s the reason why we want to bring in a new system and go, “How do we market segment this? What is it that they really want?”

Since the onset of COVID-19, managers have noticed a marked increase in the number of guests’ phone calls prior to arrival. Many suggest that staff spend a considerable amount of time learning about the purpose of guests’ visits to understand guests’ expectations. That data may be recorded to help identify what needs to be emphasized in guest communications and messaging (see “Enhance Hotel Communications with Customers”). Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

- Integrate accounting and nonaccounting data.

I would say the revenue managers now need to attend more to the industry discussions, the online discussion. It can come from government, it can come from the OTA; they have a lot [of discussions], especially for the ones that provide for corporate guests, to keep themselves up to date with the government policy.

A MORE STRUCTURED APPROACH

Our research revealed that the dominant strategy of hotels to increase profitability during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly small hotels, was to use “quiet times” (i.e., lockdowns) to upgrade their website to increase direct bookings. Although many managers suggest this tactic has resulted in significant improvements in profitability because it reduced the commissions paid to OTAs, it was widespread (i.e., more than 50% of the hotels in the study) and therefore doesn’t provide a sustainable competitive advantage. Basing revenue management decisions on a combination of market rate and intuition has the obvious benefit that it allows for rapid decision making. Without investing in a more structured approach to revenue management, these hotels risk margin leakage and leave themselves vulnerable to cash flow issues. This was the case with many of the hotels we interviewed that failed to update their revenue management strategy in response to COVID-19. We aren’t suggesting that businesses incorporate all the improvements we present here, but SMEs, which are small and more agile than their larger counterparts, can incorporate some of these with little effort to help make data-backed decisions. Even small improvements in revenue management, like developing a survey to understand the customer experience, can help managers understand how products and services are perceived to add value. Managers may be surprised how minor or inexpensive changes in a product offering and how that offering is communicated to customers can affect their willingness to pay and increase business profitability.

November 2022