The award is named in memory of Curtis C. Verschoor, a longtime member of the IMA Committee on Ethics, editor of the Strategic Finance Ethics column for 20 years, and a significant contributor to the development and revisions of the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice. Curt was a passionate, renowned thought leader on ethics in accounting, having earned a Lifetime Achievement Award from Trust Across America—Trust Around the World for his leadership in and advocacy for trustworthy business practices.

The Curt Verschoor Ethics Feature of the Year highlights an article that focuses on the importance of ethics in business as a whole and finance and accounting in particular—issues that Curt deeply cared about.

“Let’s do it just this one time, to give us some breathing room to improve performance.”

“Don’t worry about it! Everyone else is doing it, so why shouldn’t we?”

“The folks at the top, including the board of directors, would want us to handle it this way.”

Whatever wording is used to justify an otherwise underhanded action, the implication is that people behave unethically in the workplace not because they’re “bad people,” but because they don’t realize that what they’re doing is unethical. Understanding why people make unethical decisions might possibly help companies reduce the number of these poor decisions in the future. For businesses, there are a variety of explanations offered for unethical behavior, including the attitudes at the top, ethical “blind spots,” and rationalizations.

We set out to conduct a study of IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) members to help explore this issue further with funding from the IMA Research Foundation. In particular, we sought to examine two specific aspects of unethical behavior: tone at the top vs. tune in the middle and the theory of self-concept maintenance. (See “What Our Survey Asked.”)

TONES VS. TUNES

One often-cited explanation for unethical behavior is the importance of the tone at the top, something that hasn’t escaped the eyes of regulators. For example, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) requires that external auditors assess a company’s tone at the top as part of its audit of the organization’s internal control over financial reporting. A weak tone at the top is considered a material weakness under SOX Section 404, as it could imply an increased likelihood of fraudulent or misleading financial reporting. A substantial body of academic research supports this relationship.

The exclusive focus in past research on the tone at the top, however, ignores the fact that not all employees have direct interaction with the CEO, CFO, or board of directors. Many employees’ firsthand experience with management is with their supervisor, not the CEO. There are examples from the recent past suggesting that the tune in the middle plays an important role in the likelihood of fraudulent or misleading financial reporting.

In 2019, PPG Industries, Inc., a global supplier of paints and specialty coatings and materials, reached a settlement with the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) over charges that it intentionally manipulated its financial accounting multiple times to improve reported performance. After conducting an investigation, PPG fired its controller. The interesting part is that the SEC didn’t impose any fine on the company or penalties on higher-ranking officers. The U.S. Attorney’s Office also failed to pursue action against PPG or its executives. The implication is that individuals at “the top” didn’t participate in or know about the scheme.

Also in 2019, food giant Kraft Heinz Company—after receiving a subpoena from the SEC following its failure to file its 2018 annual report on time—conducted an internal investigation into accounting irregularities related to its procurement practices. The SEC concluded that while the company needed to restate its earnings for 2016, 2017, and the first three quarters of 2018, no members of senior management committed any wrongdoing.

Both of these examples point to the importance of practicing management accountants and other financial professionals, companies, auditors, and regulators focusing on the tune in the middle and the tone at the top when assessing the likelihood of unethical behavior.

WHAT IS “SELF-CONCEPT MAINTENANCE”?

Another potential cause of unethical behavior relates to individuals not fully appreciating the consequences of their actions. Why would this influence the likelihood of unethical behavior? The theory of self-concept maintenance provides one possible explanation. According to this theory, individuals faced with an ethical dilemma where they need to choose whether to gain a benefit by behaving unethically or to maintain a positive self-image by doing the right thing will find a “balance” between these two competing motivations. As long as they don’t behave “too dishonestly,” they won’t be forced to update their self-concept.

How do individuals determine what actions are “too dishonest”? Usually, it’s based on how consistent they are to their own moral standards and their ability to rationalize an action as honest. A person who recognizes that a decision has an ethical component is more likely to make an ethical decision under this theory since recognizing that a decision has an unethical component makes an action more difficult for the individual to rationalize as honest. In turn, corporate decisions having serious consequences—such as providing misleading financial data and concealing information about an unsafe product—are more likely to be viewed as having an ethical component.

CONDUCTING OUR STUDY

We used a web-based survey hosted by SurveyMonkey to collect our data. In May 2018, IMA emailed a survey link to professional members (those who aren’t students or academics) asking them to participate in our research. SurveyMonkey randomly assigned respondents to one of four categories, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

Assuming the role of controller for one of a company’s product lines, participants were asked to read a scenario and answer questions based on it. Subjects were told that they report to a product line manager, who in turn reports to the CEO. The company and product line both reported first-quarter earnings below expectations, while competitors reported earnings consistent with or above expectations. In a meeting discussing the results, the CEO states that there’s still time for the company to meet its annual earnings goals, but for this to happen, all product lines will need to improve their results.

After this meeting, the product line manager discusses with his direct reports ways to improve reported results. Our survey respondents were told that depreciation expense is one of the larger expenses on the income statement. While the company currently depreciates equipment over eight years, the case states that it could probably justify using 10 years. The case also describes how, although the annual depreciation expense will be lower with an increase in the years used, it will be difficult to detect that a change has been made without closely reading the footnotes.

We asked subjects what “most controllers” would recommend be used for depreciation based on this information. We chose this approach because a lot of ethics research indicates that asking people what “most people” would do yields results more consistent with an individual’s beliefs than asking what “they” would do.

There are four different versions of the scenario. In two versions (1 and 3), the CEO stresses that although it’s important that the company improves its results, cutting corners to do so is unacceptable. Rather, the product lines need to be true to the company’s values of satisfying customers, being accountable to all stakeholders, and being transparent in all its activities. We classify this as a strong tone at the top.

In the other two versions, the CEO states that if product lines can’t boost results by improving operations, then it may be necessary to cut corners to improve reported results (versions 2 and 4). We classify this as a weak tone at the top. Similarly, the product line manager states that cutting corners to improve reported results is unacceptable in versions 1 and 2 (strong tune in the middle) but that it’s acceptable in versions 3 and 4 (weak tune in the middle). As Table 1 shows, we have a 2 x 2 experimental design where the tone at the top and tune in the middle are consistent in two versions (1 and 4) and in conflict in two versions (2 and 3).

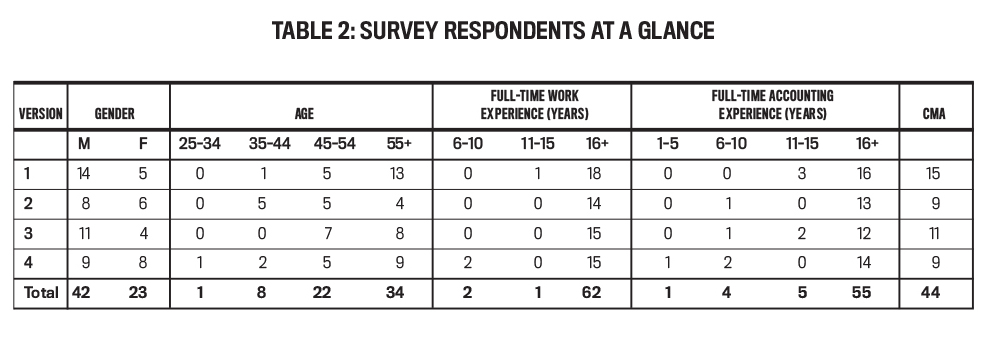

Of the 65 IMA members who completed our survey, 42 were men (64.6%) and 23 were women (35.4%). More than 50% of the subjects (34 of 65) were over 55 years old and another 33.8% (22 of 65) were between 45 and 54. Our subjects have significant experience, with 62 of 65 (95.4%) having 16 or more years of full-time work experience and 55 of 65 (84.6%) having 16 or more years of full-time accounting experience.

The highest accounting degree earned by 30 subjects (46.2%) is a bachelor’s degree, while 28 (43.1%) have a master’s degree in accounting. Only five subjects (7.7%) reported not having at least one accounting degree. Finally, 44 respondents (67.7%) hold the CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) and 21 (32.3%) hold the CPA (Certified Public Accountant). All of these factors indicate that our subjects are highly knowledgeable about, and experienced in, accounting. (See Table 2 for a more detailed breakdown of these demographic variables.)

WHAT THE RESULTS REVEALED

Importantly, one of our “tests” was to measure the influence of the tone at the top or the tune in the middle on extending a product’s recommended depreciable life in order to boost reported income. We consider a longer depreciable life to be less ethical since it increases reported income without any improvement in the company’s real economic performance.

Table 3 shows the average depreciable lives for all four versions. One interesting finding is that the highest average depreciable life is for version 4, when both the tone at the top and the tune in the middle are weak. Overall, the average recommended life with a weak tone at the top is significantly higher than with a strong tone at the top (8.52 years vs. 8.06 years). The results are similar, but less pronounced and not significant, with a weak vs. strong tune in the middle (8.37 vs. 8.18 years). When we analyze the two together, our results indicate that when the CEO demonstrates a strong tone at the top, respondents recommend lower depreciable lives, but the tune in the middle doesn’t impact the recommended depreciable life. Thus, our results indicate that the tone at the top is stronger than the tune in the middle.

We tested this another way by analyzing the differences in recommended depreciable lives when one leader’s tone changes while the other leader’s tone stays the same. That is, we tested the impact of the tone at the top by comparing version 1 to version 2 and version 3 to version 4. If the tone at the top dominates, the recommended life should be higher for version 2 relative to version 1 and higher for version 4 relative to version 3. This is because while the tune in the middle is strong in both versions 1 and 2, the tone at the top is strong in version 1 but weak in version 2.

Similarly, the tune in the middle is weak in versions 3 and 4, while the tone at the top changes from strong (version 3) to weak (version 4). While the average in version 4 is significantly higher than in version 3 (8.71 vs. 8.00 years), the average in version 2 isn’t significantly higher than in version 1 (8.29 vs. 8.11 years). This indicates that the tone at the top is sometimes stronger than the tune in the middle.

READING THE SIGNALS

In a similar way, we tested the relative strength of the impact of the tune in the middle by comparing the recommended average depreciable lives in version 3 to version 1 and version 4 to version 2. Neither the difference between versions 4 and 2, nor the difference between versions 3 and 1, are statistically significant. This indicates that the tune in the middle is never stronger than the tone at the top.

As a further test, we investigated whether having at least one person (no matter who it is) demonstrate a strong ethical tone affects decision making. We did this by comparing the average recommended depreciable life in version 4 (when both demonstrate a weak ethical tone) to the combined average for versions 1, 2, and 3. The difference (8.71 vs. 8.12 years) is significant.

We also investigated whether having at least one person (no matter who it is) demonstrate a weak ethical tone affects decision making. We did this by comparing the average recommended depreciable life in version 1 (when both demonstrate a strong ethical tone) to the combined average for versions 2, 3, and 4. The difference (8.11 vs. 8.35 years) isn’t significant. This supports the notion that rather than the tone at a particular level in the leadership chain affecting decision making, having at least one person in the leadership chain (no matter who it is) demonstrate a strong ethical tone is related to more ethical decision making.

We then tested whether subjects view a situation as having fewer ethical implications if one or both leaders demonstrate a weak ethical tone. To do this, we compared the average score on the four questions measuring the extent to which subjects believe the scenario has ethical implications for versions 2, 3, and 4 to the average score on these questions for version 1 (see “What Our Survey Asked”).

The four questions address the extent to which the decision has moral/ethical implications, the seriousness of the consequences of the decision, the consensus among accountants that the decision is moral/ethical, and how fair most people would consider the decision. That comparison wasn’t significantly different. We further tested each of these four questions individually. None of those results were statistically significant, either.

CHANGING THE FOCUS

Our final test posits that ethical behavior is directly related to the extent to which a person believes a particular situation is ethical. To test this, we ran a regression analysis with the recommended depreciable life as the dependent variable and the average score on the four questions measuring the extent to which subjects believe the scenario has ethical implications as the independent variable. The results didn’t support our expectations, but the seriousness of the consequences of the decision was marginally significant, indicating a person who judged the consequences of the depreciable life decision to be relatively more serious recommended shorter depreciable lives.

To see whether this relationship differs based on ethical tone, we looked at the recommended depreciable lives based on how seriously subjects viewed the consequences of the decision and whether the tone at the top and tune in the middle were both weak (version 4). As shown in Table 4, the average recommendation of nine years—for when both the CEO and product line manager demonstrate weak tones and the consequences are considered less than extremely serious—is significantly greater than the average of eight years, when both the tone at the top and tune in the middle are weak and the consequences are considered to be extremely serious.

The average of 8.19 years—when at least one leader demonstrates a strong ethical tone and the consequences are considered to be less than extremely serious—is marginally significantly higher than the average of eight years, when at least one leader doesn’t demonstrate a strong ethical tone and the consequences are considered to be extremely serious. These two results indicate that the impact of whether someone considers the consequences of a decision to be extremely serious is more pronounced when both the tone at the top and tune in the middle are weak than when one or both are strong.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ACCOUNTANTS

We set out to test whether the tone at the top or the tune in the middle plays a larger role in the recommendations that management accountants make about the depreciable life to use for financial reporting purposes. Our results indicate that the tone at the top generally plays a more significant role than does the tune in the middle.

There is some evidence, however, that a more ethical tune in the middle partially (but not completely) reduces the impact of a less ethical tone at the top. There are two implications of this. First, the CEO (“the top”) needs to be aware of the impact his or her statements and actions have on subordinates. Second, direct supervisors (“the middle”) also have an impact on their subordinates, just not to the same extent as the CEO has. This is particularly important when the CEO demonstrates a weak ethical tone.

A second implication of our findings is that how serious people believe the consequences of their decisions to be has an impact on behavior, but only when a leader (the CEO, direct manager, or both) demonstrates a weak ethical tone. Specifically, those who believe the consequences of the depreciable-life decision to be extremely serious recommend shorter lives than those who believe the consequences to be less serious when one or both leaders demonstrate a weak ethical tone.

When both leaders demonstrate a strong ethical tone, however, there’s no statistical difference in recommended average depreciable lives based on the seriousness of the consequences. This indicates that accountants could be placing themselves in the greatest personal jeopardy by behaving ethically when both of their supervisors seem to be advocating unethical behavior and they view the consequences of their decision to be extremely serious. This is consistent with the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice’s requirement that members “place integrity of the profession above personal interests” and that they demonstrate integrity by contributing to a “positive ethical culture” in their organizations. Most management accountants, we’ve found, do act consistently in this regard.

A related implication is that it’s important to educate management accountants about the seriousness of the consequences of the decisions they make, especially when the tone at the top and/or the tune in the middle are relatively weak. It’s plausible to think that accountants will focus more on a decision’s consequences when one or more leaders seem to advocate unethical behavior because they realize that their leaders aren’t setting a good example for others to follow. And finally, this also demonstrates a commitment by management accountants and other financial professionals to create a positive ethical culture in their organizations, especially when leadership demonstrates a willingness to commit or condone unethical behavior.

March 2021