How can companies create greater long-term sustainable value that benefits all stakeholders and overcomes the focus on short-term returns or corporate short-termism? According to the latest research from the Return Driven Strategy Initiative at DePaul University’s Kellstadt Graduate School of Business, short-termism is a major barrier to long-term value creation. This is an area where CFOs and finance organizations can play a leadership role in helping their companies create greater long-term value. In his book, Curing Corporate Short-Termism: Future Growth vs. Current Earnings, Gregory V. Milano presents actionable ways to help companies avoid short-termism and create greater long-term value.

FRIGO: Based on your experience, what are the root causes of short-termism?

MILANO: There are many motivations for the short-termism actions we often see, especially in large public companies. It’s common to blame it all on investors, analysts, and journalists, and at times these groups do demand actions from management that are at odds with thinking longer-term. But over the last 30 years I have found in most companies that more of the problem originates from within rather than from external pressures. Recognizing and accepting this is the first step on the journey toward building a culture of long-term ownership.

FRIGO: What are some of the internal drivers of short-termism you have noticed?

MILANO: One of the biggest internal drivers of short-termism is the use of performance measures that respond poorly to investments in the future. For example, consider the increasingly widespread use of rates of return on invested capital (ROIC) over the last few decades. Most managers don’t realize how such measures can bias them against investment. To see it clearly, consider a business with assets that on average are, say, half-depreciated. When we invest in new assets, either as replacements or for growth in capacity, putting these undepreciated assets in the mix with all the partially depreciated assets tends to increase the ROIC denominator more than the numerator, so except in the case of really valuable projects, investing tends to reduce ROIC. For an asset with a 10-year life, it’s common for it to take three to four years for the new asset to depreciate enough that it has a positive incremental impact on corporate-wide ROIC.

FRIGO: That’s very consistent with research from the Return Driven Strategy Initiative, which finds that a major cause of short-termism is the use of the wrong performance measures, many of which are traditional performance measures. Based on your experience, how do traditional measures used at companies lead to short-termism?

MILANO: Traditional return measures like ROIC tend to reduce investment in the future, as do economic profit measures that use net depreciated assets as invested capital. Also, depreciation breaks down accountability. As assets depreciate, ROIC and economic profit rise almost automatically, giving the illusion of value creation.

In addition, percentage measures, such as margins and returns, tend to discourage investment in good businesses and encourage it in weaker ones. If you’re paid to drive EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) margin or ROIC higher, and your performance is already very high on the measure, almost everything you consider doing would bring down the average and reduce your pay. This disincentive to invest in good businesses makes them appear mature long before their time, which again causes short-termism. But if your margins or returns are low, almost anything brings up the average, and in an odd paradox, we find many companies reinvest too high of a percentage of cash earnings back into their weaker businesses, which is a big problem.

FRIGO: What measures do you recommend to help combat short-termism?

MILANO: In Curing Corporate Short-Termism: Future Growth vs. Current Earnings, I explain how residual cash earnings (RCE) can overcome each of these problems to encourage more investment and more accountability. We designed RCE to reflect performance in a well-distributed way over the life of an asset. We accomplished this simply by not charging depreciation or recognizing accumulated depreciation as a reduction in asset value. We also treat research and development (R&D) as an investment rather than as an expense, which is really important these days since intangible assets like brands and technologies are increasingly important relative to tangible assets. RCE is measured in dollars to avoid the percentage problem we’ve mentioned already—RCE responds to quality and quantity of activity. This simple measure motivates better behavior than traditional margin, return, or economic profit measures, and it relates better to total shareholder return (TSR) too.

Having used CFROI (cash flow return on investment) in your own research, Mark, you’ll notice that the depreciation approach is similar to the HOLT CFROI framework, which is where I got the idea. When I worked with HOLT at Credit Suisse, I realized how depreciation distorted traditional measures of return over the life of an asset, so we incorporated the approach into our simpler RCE metric that we find more implementable across the operations of a business.

FRIGO: In your work, you suggest that understanding short-termism and its negative outcomes results from a culture driven by “variance to plan” rather than “up is good and down is bad,” and how better measures enable this shift. Would you describe a few examples of the better measures that would resonate with CFOs?

MILANO: For more than a decade, I’ve been saying that measuring performance against plans and budgets is one of the biggest problems in business. Once managers know they will be measured against their plan, in operating reviews and incentive programs, they realize they’re better off if they put forth a conservative plan that they believe can be easily beaten. We’re paying them to plan on being mediocre! The technical financial planning and analysis term for this is “sandbagging.”

RCE is a complete measure where “up is good and down is bad.” It balances growth, margin, and capacity utilization better than any other measure, so we can stop measuring against a plan and instead measure against last year. RCE rises whenever management improves growth and/or margin in ways that don’t require investment. And when investment is needed, RCE includes a capital charge on that investment, and it therefore shows us if the investment was worth it.

In our recommended incentive plan, if RCE equals the prior year, a target bonus is earned. If RCE rises, so does the bonus, and vice versa. Imagine how much more successful managers would be if the planning process were unencumbered and they could strive for success in every way imaginable.

Consider what happens when a CEO suggests some ideas for improvement to a business unit leader. In the variance-to-plan world, the business unit leader gets defensive and explains why these ideas shouldn’t be added to the plan, lest they would be raising the bar against which they’re ultimately measured. But when improvement in RCE vs. last year is the way, such ideas would be taken in and considered with great interest. Anything that would make performance better is good—helping the CEO and business unit leader to become strategic partners, not adversaries in a negotiation of performance targets.

FRIGO: The life-cycle framework can be a powerful tool to help companies create greater long-term sustainable value, as described in a recent SF article (see “Strategic Life-Cycle Analysis: The Role of the CFO,” by Mark L. Frigo and Bartley J. Madden). How can the concepts and tools in your book be deployed to help companies conduct strategic life-cycle analysis?

MILANO: Though we come at it somewhat differently, our approaches are really two sides of the same coin. We’re both “combating incrementalism,” as I call it. Being content is a value trap for businesses, as you’re either getting better or getting worse. As soon as management becomes satisfied with the status quo, it opens the door to competitors, and the decline begins. Your article with Bart refers to this as competitive fade. It isn’t always something management does that’s wrong; it’s the lack of doing things that are right in order to keep advancing ahead of competition.

We also recognize the shortcomings in accounting (as discussed in your article with Baruch Lev: “Regaining Relevance in Financial Reporting,” Strategic Finance, January 2019, especially as it pertains to “new economy” activities, where the assets are often intangible rather than tangible. Treating R&D as an investment is critical, as is the treatment of other investments, such as brand-building advertising and employee training, when they’re significant drivers of value. We seek the situation where a performance measure works just as well for new and old business models so companies that are managing a mix of both can be better steered toward the right decisions.

FRIGO: The ideas described in this article are very consistent with companies that adhere to the Return Driven Strategy framework, especially Tenet 1, “Ethically Maximize Wealth,” which means ethically creating long-term sustainable value, including stakeholder value.

The recommendations in this article are also consistent with the “Disciplined Performance Measurement and Valuation” foundation of Return Driven Strategy, which means having performance measures that are highly aligned with long-term value creation and highly aligned with the drivers of valuation. Companies adhering to the Return Driven Strategy framework reinvest more in the business and more consistently than short-term organizations, which is also consistent with the Corporate Horizon Index (see Measuring the Economic Impact of Short-Termism, February 2017, McKinsey Global Institute.

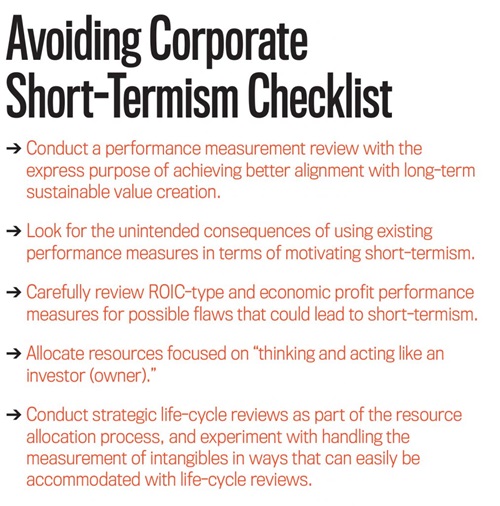

CFOs and finance organizations in companies have a great opportunity to develop better alignment of internal performance measures to long-term sustainable value creation. This can be done by carefully reviewing existing performance measures, including return on investment measures used at the company, and developing an action plan.

This article is part of the Creating Long-Term Sustainable Value series launched by the October 2018 Strategic Finance article “Creating Greater Long-Term Sustainable Value,” by Mark L. Frigo, with Dominic Barton.

April 2021