Intangible assets are a primary driver of value creation in companies, but with only rare exceptions, the values of intangible assets are notoriously difficult to measure. Intangible assets are considered “too soft” to be included in the financial statements used for financial reporting purposes. Yet because of their importance, it’s essential that these assets, and the expenditures designed to create these assets, be managed well. This provides some difficult challenges for managers and the measurement experts on whom they rely: management accountants and CFOs.

One major category of expenditures designed to create intangible assets is in the marketing area. Marketing professionals are under ever-increasing pressures to justify their companies’ marketing investments (see “The Financial Value of Brand,” Strategic Finance, October 2019, bit.ly/3cRxKZY). Critics have contended that the marketing function often fails to demonstrate its worth. When marketing professionals can’t justify their expenditures in terms of the benefits to the business, their stature and trust within the company are both diminished. Consequently, they have greater difficulty in securing and retaining allocations of resources. Their marketing expenditures tend to be viewed as discretionary expenses, easily cut when need be (as evidenced by marketing budgets being slashed in down cycles). So marketing professionals should want to be held accountable for results to help justify future investment. For years, the Marketing Science Institute has asked that research priority be placed on helping marketing professionals prove their value relevance.

Management accountants can help. They have expertise in measuring both the benefits and costs that go into the analyses needed for justifying new expenditures and in analyzing the expenditure justifications.

THE CHALLENGE

Measuring the outcomes of marketing expenditures isn’t easy. Traditional summary financial accounting outcome measures, such as net income and accounting returns, are of limited use in the short run because they don’t reflect the value of intangible assets, such as brand equity and customer loyalty, created by the marketing investments. Accounting rules for financial reporting purposes require the immediate expensing of these types of expenditures. This means that the more that’s spent to create these intangible marketing assets, the worse the organization appears, according to these metrics, in the short run.

Other common marketing outcome metrics are sales and market share. Neither of these outcome measures is reliable, either. Sales is limited as an outcome measure because not all sales are profitable. The cost of generating the sale can be greater than the revenues generated. Similarly, the linkage between market share and value creation is tenuous. Studies on the topic have found most attempts to compete to improve market share reduce profitability, and relationships between market share and value creation are at best correlational, rather than causal (see “Competitor-Oriented Objectives: Myth of Market Share” by J. Scott Armstrong and Kesten C. Green in Volume 12 of the 2007 International Journal of Business). Bruce Henderson, the founder of the Boston Consulting Group, even wrote in the 1989 Harvard Business Review article “The Origin of Strategy” that “market share is malarkey.” While sales and market share continue to be commonly used marketing metrics, their limitations have long been recognized.

All of these global outcome measures are also limited in value because they’re affected by many other factors, including other investments being made concurrently and changes in the economy and competition. More direct indicators of the success of the marketing spend are needed.

CREATING MARKETING ASSETS

In the vast majority of situations, the only way to reliably demonstrate returns from marketing expenditures is to use the metrics suggested by business models linking marketing expenditures with the creation of “marketing assets.” Sometimes these metrics are referred to as some form of return on marketing investment (ROMI). Definitions of ROMI vary, so considerable confusion about that term exists. What is key, though, is that the marketing expenditures buy or build marketing assets with the expectation that they will benefit the business in the future.

Marketing expenditures create two forms of marketing assets: brand value and customer equity. Both are intangible. Brand value is a proxy for the future improvement in cash flows attributable to the marketing activities undertaken during the period. It’s reflected in customer awareness, satisfaction, and preference. Customer equity is an alternate way to measure the same future benefits since customers buy the business’s products. Customer equity can be measured in terms of customer numbers, customer types, share of wallet, and retention. These intangible marketing assets are just as, or perhaps even more, valuable to the business as hard assets like property, plant, and equipment. Managers need to estimate and track changes in these intangible asset values in order to manage the marketing expenditures properly.

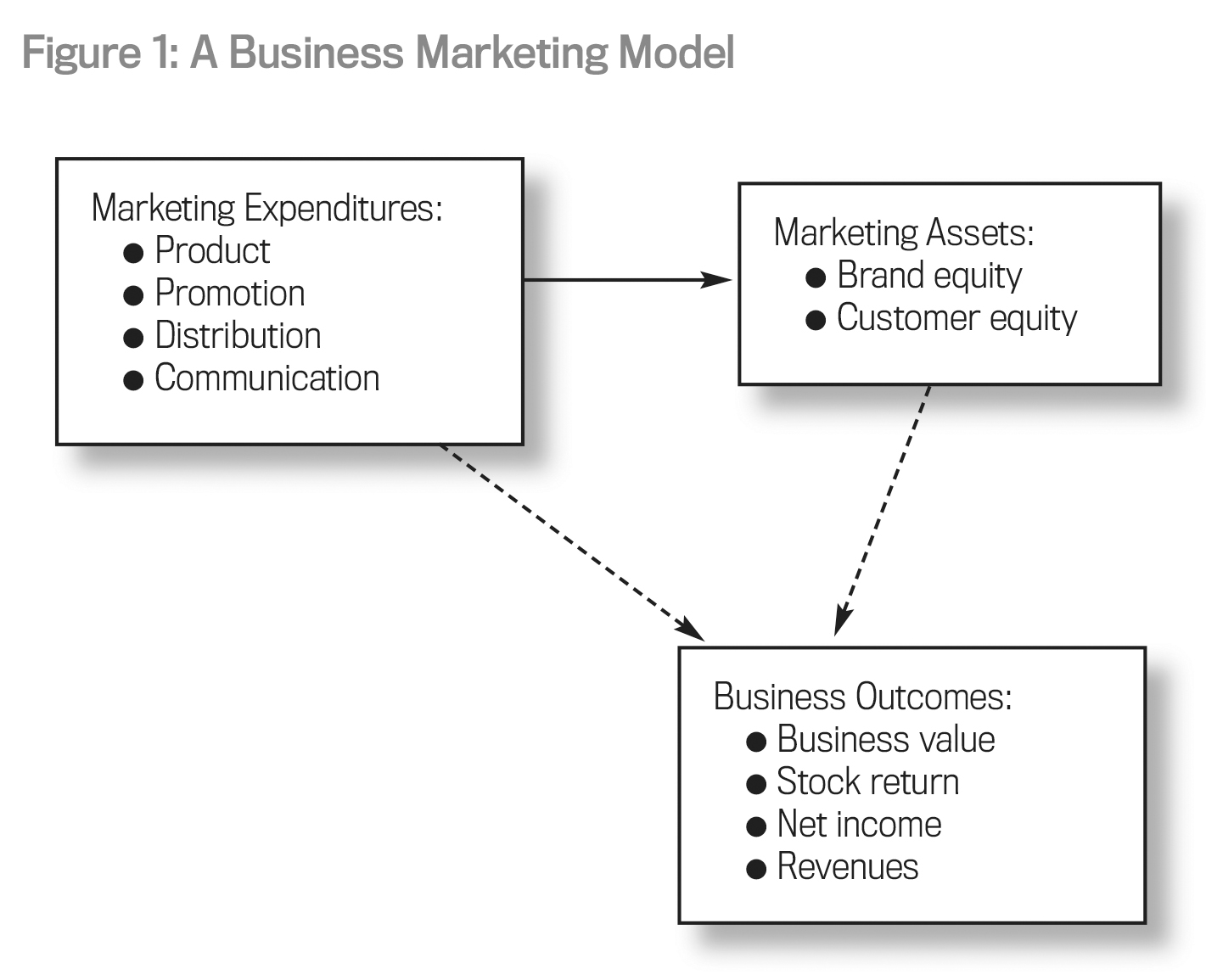

Figure 1 shows a typical business marketing model. It’s difficult, and usually even impossible, to track the direct effects of marketing expenditures on global indicators of business success, as explained earlier. The dotted lines in Figure 1 refer to assumed, but unmeasurable, relationships between the marketing expenditures and marketing assets and important business outcomes. But it’s possible to track the effects of marketing expenditures on the creation of marketing assets.

MORE SPECIFIC MEASURES

With this general marketing model in mind, the remaining task is to develop the specifics of the model. Many marketing activities require expenditures, such as for market research, traditional advertising, internet presence, promotions, trade shows and events, marketing planning, customer relationship management, and various forms of communications. The important categories of expenditures need to be discussed separately and kept separate in the accounting records.

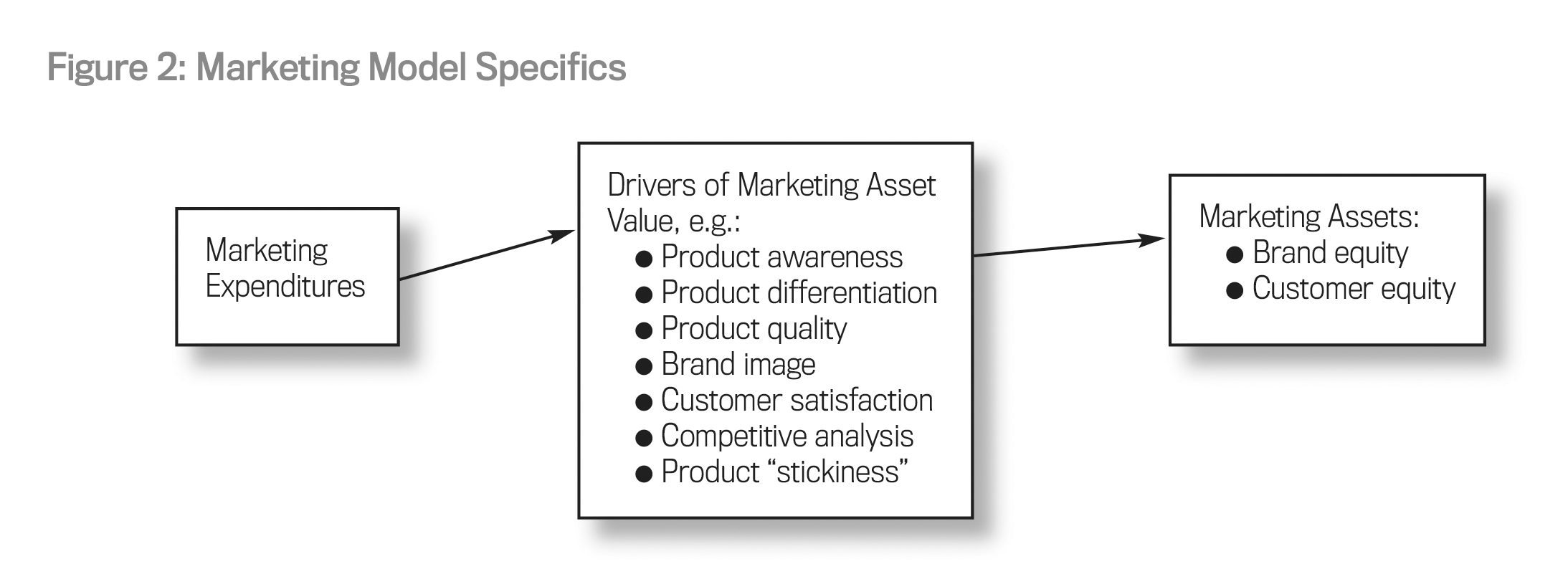

When expenditures for these types of activities are proposed, the expected benefits on the creation of specific marketing assets need to be made clear. The types of expenditures to be made and their expected benefits will vary significantly across business types. For example, expenditures on advertising are intended to create customer awareness, impressions, reach, and recall. In the digital world, expenditures on internet advertising can be measured in terms of hits/visits/page views and click-through rates. Expenditures to build sales force capabilities are designed to improve reach, number of customer responses, and retention rates. Expenditures on price promotions should result in reach, impressions, trials, and repeat volumes. These intermediate elements of the marketing model are the drivers of the value of the marketing assets (see Figure 2). As such, they’re all miniature proxies for future cash flows and value creation. Knowing them provides the key to being able to develop metrics that can be used to justify the marketing expenditures made.

If the impacts of some of these types of expenditures are unclear, companies should conduct experiments to test the expectations built into the model. That is, they should vary the expenditures and track the variance in the effects. One of the benefits of digital marketing is that it provides relatively easy opportunities to test the links between inputs and outputs.

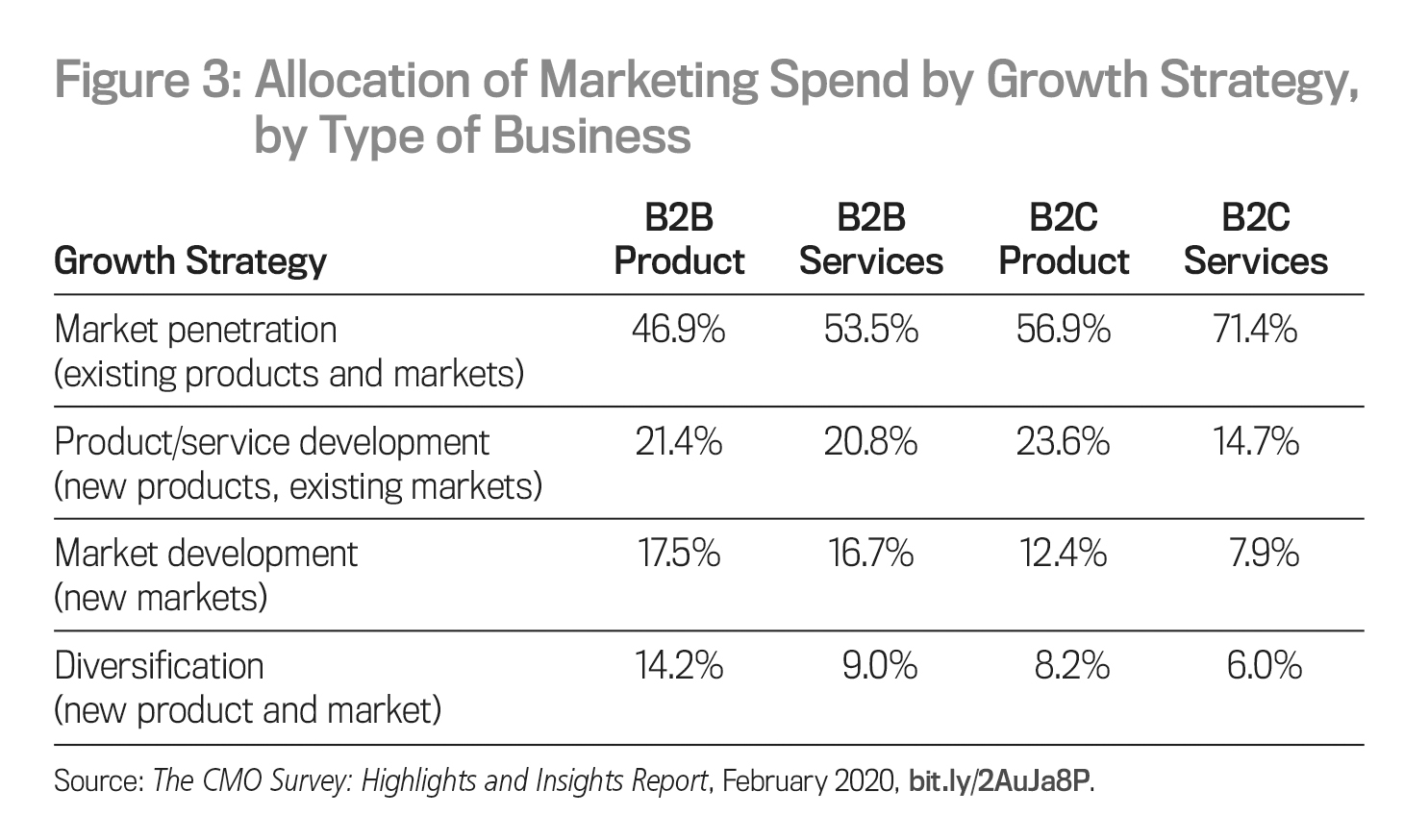

It’s also important to specify the time period over which the benefits will be forthcoming. Some expenditures are designed to produce immediate benefits. For example, the mix of marketing expenditures varies significantly with a business’s growth strategies, as shown in Figure 3. Spending on existing products and services provides a shorter window in which to realize return on investment than diversifying into new markets that are unknown.

Proposals for marketing expenditures have to be defended with promises of measurable outcomes in mind. These proposals set the expectation. The final step in the accountability process is to compare the outcomes with the expectations. This is increasingly being done. According to the The CMO Survey: Highlights and Insights Report from August 2017 (bit.ly/2zpq43s), for example, the use of marketing analytics was expected to grow 229% (as a percentage of marketing spend) over three years. These analyses provide increased understanding and increased accountability, which lead to improved allocations of resources and also more effective and more efficient use of the expenditures. They will help the marketing discipline develop a reputation for delivering results. The increased accountability should result in a greater willingness from top management to make marketing investments, which will benefit both the marketing function and the business.

Management accountants and CFOs can play important roles in working with marketing professionals to improve the development of measures and accountability processes. Metric development and justification of business expenditures are at the core of the expertise of the management accounting function.

Editor’s note: An error in the headline of this article in the print edition of Strategic Finance has been corrected in this online version.

July 2020