It’s natural to focus on upper management and the board of directors when attempting to promote ethical behavior, as it is believed these groups are likely to have the largest impact on the greatest number of employees in an organization. But not all employees have direct interaction with the CEO, CFO, or board of directors. They may hear rumors concerning how upper management behaves or even hear what upper management has to say in meetings or other settings, but they don’t experience management’s behavior firsthand.

Their experience with management is dominated by interactions with immediate supervisors. The behavior of these individuals could have greater influence on employees’ approach to ethical behavior. In other words, the “tune in the middle” may be more relevant to their decision making than the tone at the top. In fact, participants in a 2010 study on reducing financial statement fraud conducted by the Center for Audit Quality made the point that a first-line supervisor plays a larger role in influencing a person’s ethical judgment than upper management does.

For example, Panasonic Corporation incurred penalties of more than $280 million in 2018 when two executives of a business unit admitted to violating accounting rules without oversight by anyone at the business unit or the parent company. In 2015, a former chief accounting officer of Beazer Homes was sentenced to 10 years in prison after being found guilty of conspiracy and obstruction of justice charges related to a seven-year accounting fraud at the company. While Beazer’s CEO and CFO were required under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act to return certain compensation resulting from the accounting fraud, neither were charged with any misconduct.

And JPMorgan Chase & Co. was forced to restate a number of U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) filings and disclose material internal control weaknesses with respect to the London Whale trading scandal in 2012. A subsequent investigation revealed that lower-level employees who committed and covered up the fraud provided Chase CEO Jamie Dimon and the board of directors inaccurate information as a way to cover up the fraud (see “The Tale of a Whale,” Strategic Finance, April 2015). In all three of these cases, leaders below the “tone at the top” level committed fraud without apparent knowledge of their superiors.

In 2010, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) analyzed SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAERs) issued between 1998 and 2007 and found that, while the CEO or CFO was listed as being involved in 89% of investigated financial statement frauds, controllers were listed in 34% of cases and other vice presidents were listed in 38% of cases. Since the analysis focused on the highest-ranking person listed in the AAERs, it’s reasonable to conclude that people below the top corporate ranks perpetrated at least some of these financial statement frauds.

The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse: 2018 Global Fraud Study reports that while upper/executive management is the single largest group that committed financial statement fraud, people below those levels committed close to 70% of financial statement frauds. Finally, a 2016 worldwide study by PwC finds that while 98% of survey respondents believed their top management is committed to ethical behavior, only 16% considered their CEO to be the “ethics champion” at their organization.

What’s the common thread among these examples? They all indicate that it’s important to look beyond just upper management when considering the standards and expectations for ethical behavior among employees. It’s important for management accounting and financial professionals, internal auditors, and external auditors to focus on both the tone at the top and the tune in the middle when assessing the likelihood of unethical behavior taking place in an organization.

People below upper management are likely to be involved in the development and assessment of internal control systems and in making financial reporting decisions. If the individuals making these decisions and assessments focus on their immediate supervisor’s behavior and attitudes rather than those of the CEO, then focusing attention on the CEO’s behavior and attitudes isn’t likely to reduce aggressive financial reporting or even financial statement fraud.

TESTING THE TUNE IN THE MIDDLE

We conducted an experiment to test the theory that an employee will focus on the tune in the middle rather than the tone at the top. Using two different audiences, we asked study participants to assume the role of controller for a product line of a hypothetical company and to complete a scenario related to the company’s first-quarter earnings.

As the controller, respondents report to the product line director, who then reports to the CEO. The company as a whole and the product line both reported first-quarter earnings that are below expectations, while competitors reported earnings consistent with or above expectations. In a meeting discussing the results, the CEO announces that there’s still time for the company to meet annual earnings goals, but all product lines will need to improve their results. After this meeting, the product line director meets with his direct reports, including the controller, to discuss ways to improve the results.

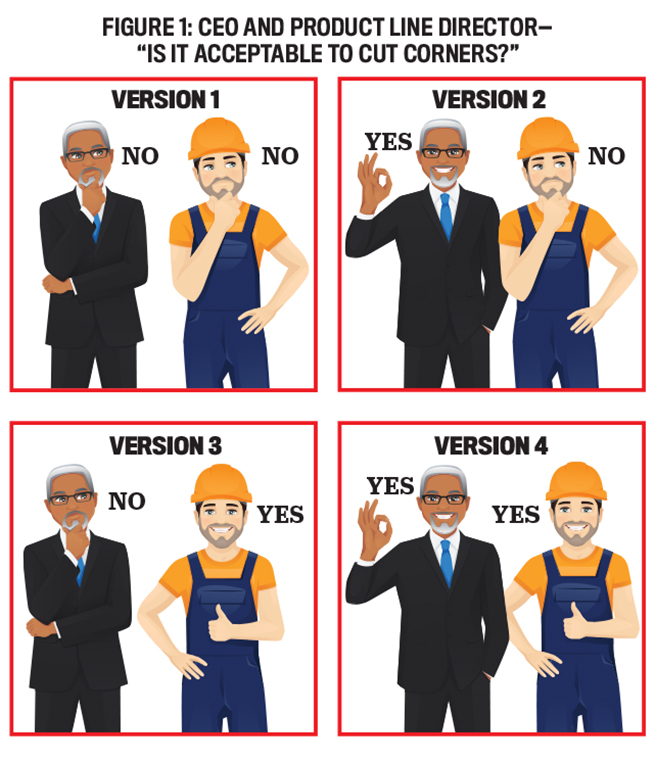

There are four different versions of the scenario. In two versions (versions 1 and 3), the CEO stresses that although it’s important the company improve its results, it’s unacceptable to cut corners in order to do so. Rather, the company and product lines need to be true to the company’s values of satisfying customers, being accountable to all stakeholders, and being transparent in all its activities. In the other two versions (versions 2 and 4), the CEO states that if product lines can’t improve results by improving operations, then it may be necessary to cut corners to improve reported results.

Similarly, the product line director states that cutting corners to improve reported results is unacceptable in two versions (versions 1 and 2), while stating that it’s acceptable in two versions (versions 3 and 4). This results in a 2x2 experimental design where the “tone at the top” and “tune in the middle” are consistent in two versions (versions 1 and 4) and in conflict in two versions (versions 2 and 3). See Figure 1 for a summary of these scenario versions.

We told the participants that depreciation expense is one of the largest expenses on the company’s income statement and that while the company currently depreciates equipment over eight years, it could probably justify using 10 years to calculate depreciation expense. We also told them that it would be difficult for statement readers to detect a change in the useful life without their closely reading the footnotes.

We randomly assigned each participant to one of the four versions. (See “Our Survey” at the end of this article for more details on the study and its participants.) We then asked them to provide the number of years they would recommend the company use for depreciation purposes and gave them an opportunity to explain the reasoning behind their choice, although very few did. After that, participants answered six questions testing the extent to which they understood the case materials as well as several demographic questions.

VALIDATING THE SCENARIOS

In order for our experiment to test the impact of the tone at the top and the tune in the middle on the participants’ choice of depreciable life, participants had to perceive that the CEO’s and product line director’s beliefs about cutting corners were consistent with the version of the experiment they received. In other words, if participants were told in the materials that the CEO believes cutting corners is unacceptable but the respondent perceives that the CEO believes cutting corners is acceptable, the experiment isn’t valid.

To test this, we asked respondents questions to gauge their views of the CEO and product line director, including:

- The extent to which they believed the CEO and product line director are committed to transparency (very uncommitted, somewhat uncommitted, neither uncommitted nor committed, somewhat committed, and very committed),

- The extent to which they believed the CEO and product line director are committed to accountability (very uncommitted, somewhat uncommitted, neither uncommitted nor committed, somewhat committed, and very committed), and

- Their opinion on whether the CEO and product line director believe cutting corners to improve short-term results is acceptable (yes or no).

In versions 1 and 3, participants should perceive the CEO as relatively more committed to transparency and accountability and less accepting of cutting corners than in versions 2 and 4. Similarly, participants should perceive the product line director as relatively more committed to transparency and accountability and less accepting of cutting corners in versions 1 and 2 than in versions 3 and 4. The statistical analysis of the responses to these questions supports the fact that participants perceived the CEO and product line director consistently with the way we portrayed them in the different versions of the scenario. This increased our confidence that the study could provide useful evidence about our research question.

THE RESULTS

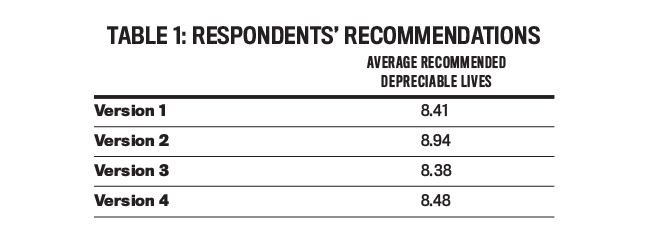

Table 1 shows the average recommendations for each of the four versions. One notable result is the recommendation for version 1, which we refer to as the base case because both the CEO and product line manager are perceived as finding it unacceptable to cut corners to improve results. In spite of the expressed views of the CEO and product line director, participants recommended increasing the depreciable life to 8.41 years, which is statistically significant.

This indicates that practicing accountants are willing to adjust accounting estimates to improve reported results even in the absence of any stated cues from those above them in the chain of command. The simple fact that operating results aren’t up to expectations may be enough to trigger a change in accounting estimates. This is potentially dangerous to the accounting profession.

Another interesting fact is the difference in results between when only the CEO seems accepting of cutting corners to improve reported results (version 2) and when only the product line director seems accepting (version 3). The recommended depreciable life of 8.94 for version 2 is greater than both the initial eight-year life as well as the 8.41-year life in the base case. The increases from both are statistically significant. This indicates that respondents strongly reacted to the CEO’s statement justifying cutting corners to improve reported results.

Yet when only the product line director seems accepting of cutting corners (version 3), the recommended life of 8.38 years represents a statistically significant increase from the initial eight-year standard, but it isn’t significantly different from the base case. One possible explanation for this could be that participants believed that the product line director could rely on changes in areas other than accounting to improve reported results. For example, the division could reduce advertising or training costs to improve reported results, resulting in the need to make smaller accounting changes. These nonaccounting options may not be available without the product line director’s involvement.

Also, the depreciable life of version 2 is statistically significantly higher than version 3. In other words, participants paid more attention to the CEO than to the product line director when making their decisions. The evidence from these comparisons between versions 2 and 3 collectively indicates that respondents paid more attention to the tone at the top than to the tune in the middle.

One other result of note concerns the differences in the recommended depreciable life between when both the CEO and product line director appear to accept cutting corners (version 4) and when only one of them appears accepting of this behavior. The recommended life of 8.48 years in version 4 is higher than when only the product line director seems accepting (version 3, 8.38 years), but the increase isn’t statistically significant. In addition, the version 4 recommended life is statistically significantly lower, not higher, than when just the CEO seems accepting of cutting corners (version 2, 8.94). In other words, respondents recommended longer depreciable lives when just the CEO seems accepting of cutting corners than when both the CEO and product line director seem accepting of cutting corners.

Participants apparently paid attention to the tune in the middle, just not in the way the product line director intended. One possible explanation for this could be that if multiple management levels accept cutting corners, accounting professionals might believe that other parts of the company are taking actions to improve reported results and, thus, they don’t “need” to change accounting estimates as much. Since larger accounting estimate changes may bring regulatory or investor scrutiny, accounting professionals recommend smaller changes in this scenario.

An alternative explanation for the difference in results for version 4 compared to version 2 is that when multiple levels of managers accept cutting corners, accounting professionals might believe that the organization’s ethical environment is relatively weak and they need to “take a stand” against more aggressive accounting. When only the CEO appears accepting of cutting corners, perhaps accounting professionals see changing accounting estimates as less damaging to the future of the company than cutting corners in other parts of the company (for example, spending less on marketing or using lower-quality materials in production) and are willing to make larger changes to estimates. But when multiple levels appear to be involved in cutting corners, perhaps accounting professionals see changing accounting estimates to improve reported results as a tacit endorsement of potentially unethical behavior and aren’t willing to recommend relatively large changes.

CREATING AN ETHICAL CULTURE

Our study indicates that signals from top-level executives appear to have more influence on accounting professionals deciding to lengthen the life used to calculate depreciation expense for financial reporting purposes than do signals from midlevel managers. Signals from midlevel managers appear to have little influence on this decision in our study. That is, accounting professionals paid more attention to the tone at the top than the tune in the middle.

For senior-level executives the message from our results is clear: Watch what you say and do, as people throughout the organization are paying attention. For those assessing the risk of financial statement fraud in an organization, the message is also clear: Pay attention to what senior-level executives say and do.

Our results also apply to management accountants at all organizational levels. As noted previously, the average recommended life in all four versions exceeded the original eight-year life, even in version 1 where both managers disapproved of cutting corners. This means that individuals were willing to adjust accounting estimates to improve reported results, even without any encouragement from management.

One way to combat this is to stress the importance that all people have in building a strong ethical culture—it isn’t just management’s responsibility. For example, the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice explicitly states that management accountants demonstrate integrity by contributing to a positive ethical culture and placing the profession’s interests over their own personal interests. Management accountants should take the lead in helping their organizations develop positive ethical cultures.

SETTING AN ETHICAL EXAMPLE

Regardless of your position within a company, you can help establish an ethical culture through leading by example.

An obvious start is to follow all applicable laws, regulations, and company policies. For instance, if the company has a rule mandating flying in coach, the leader should not use company funds to fly first-class. Or, if the company has per-day limits on hotel expenses, the leader shouldn’t exceed them. While these examples may not be large expenses, it can send a signal to others in the organization that not all rules need to be followed. Once individuals believe rules are mere suggestions, culture can break down. Another way to establish a positive ethical culture is to hold those violating laws and policies accountable. Without consequences, violations are likely to increase.

Those at the top of organizations can contribute to an ethical culture by influencing the organization’s vision, mission, and strategy. The level of risk an organization is willing to take and its operating philosophy can both influence its ethical culture. Another way is through the budgeting process. If a company allocates insufficient funds for initiatives to encourage ethical behavior such as training programs, those initiatives are unlikely to promote a strong ethical culture.

Those at other levels of leadership can also have an influence by ensuring that his or her direct reports understand the importance of company training concerning conflicts of interest and other ethical issues. If a manager sends a signal that employees should view training as a distraction from their regular work and should be completed as quickly as possible, employees aren’t likely to internalize the material. Yet if the manager sends a signal that the training is an integral part of their work, employees are more likely to take the training seriously.

Another way is through decisions they make on a daily basis. The depreciation decision in this study is one example. While a 10-year life may be defensible, it isn’t the “best” figure to use. Another example concerns dealing with employees. If a manager appears to not treat all employees fairly, the organization’s culture can suffer.

OUR SURVEY

We used two different samples to test our case scenarios: a group of 135 graduate accounting students enrolled in a Master of Accountancy (MAcc) program at a large private university and 24 IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) members who completed the survey as part of a Research Lab program held at an IMA Annual Conference & Expo.

While the student population is heavily female (95 out of 135), the IMA sample is more evenly split (11 female and 13 male). Not surprisingly, the student population had less overall work experience and less accounting-related work experience at the time of the survey. Of the 135 students, 86 had at least some full-time accounting work experience and 129 had at least some full-time work experience in any field.

We decided to drop the 49 students having no full-time accounting work experience since all 24 IMA members had full-time work experience in accounting. That left a sample of 110 participants (86 students and 24 IMA members) well-versed and experienced in accounting.

Prior to conducting the study, we asked two professional accountants with significant accounting experience to review the case scenarios to ensure they were realistic. We revised the scenario based on their comments. We then had MBA and MAcc students (separate from the individuals used in this study) complete the research instrument to confirm that it was written clearly and easy to understand. These test participants didn’t report any problems completing the instrument.

February 2020