By 2012, JPMorgan Chase & Co. had racked up $6 billion in trading losses on a specialized derivatives portfolio designed to manage risk. After investigators found serious failures in internal controls and fair value accounting measurements, JPMorgan agreed to pay approximately $920 million in fines to regulators in the United States and United Kingdom. But the fallout didn’t end there. The scandal threatened the reputation and career of JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon, two traders were charged with securities fraud, and the scandal became the catalyst for regulators to finalize new rules banning publicly insured banks from doing speculative trading.

A BAD TIME FOR BANKS

The trading scandal couldn’t have happened at a worse time for banks. It roughly coincided with the writing, passage, and implementation of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. At the time, banks were actively lobbying against the Volcker Rule, Section 619 of the Act, which banned publicly insured banks from doing speculative trading.The actions—and inactions—of JPMorgan management during the trading scandal violated U.S. federal securities laws and became a major test of the internal control sections of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX). Happening when it did, it’s possible that the scandal was the straw that broke the camel’s back, ensuring the adoption of the Volcker Rule.

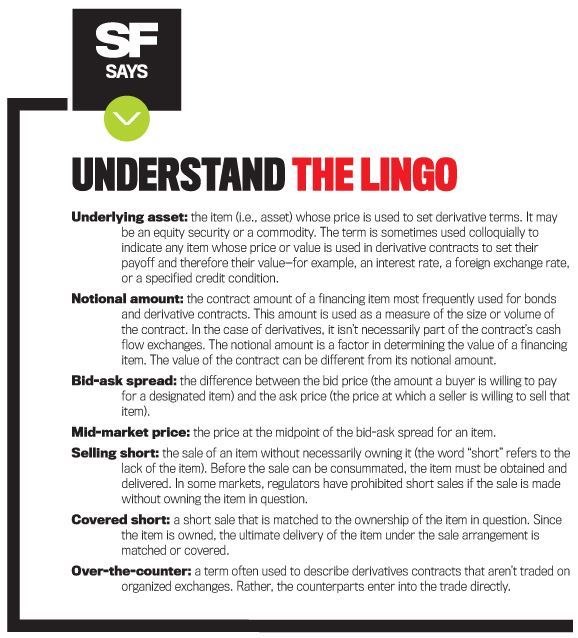

The debacle involved a combination of breakdowns in internal controls, inept risk oversight, trading gone wrong, bad luck, and faulty, if not fraudulent, accounting. (The discussion of the scandal can get a bit technical, so see “Understand the Lingo” for a review of some derivatives accounting and trading terms.)

So how did it happen? And could management accountants have prevented it?

THE LONDON WHALE

The JPMorgan scandal involved a trader in its London office who became known as the “London Whale” because of the size of his market bets (see “Why a Whale?”). The scandal-causing trade was initiated as early as 2008, and it continued with dynamic modifications over four years before the losses became irreversible and unavoidable.

The trade was a position in derivatives initially authorized by senior management and was a partial response to the Third Basel Accord (Basel III), a global voluntary standard for the adequacy of bank capital, stress testing, and market liquidity risk. Basel III impacted the calculations that determine how much capital banks need to hold measured against their risk-weighted assets. JPMorgan estimated that Basel III would require it to either increase the amount of capital it held or reduce its risk-weighted assets. In anticipation, JPMorgan set out to reduce risk, among other actions.

The contracts for the trade were designed to generate gains as credit deteriorated in selected markets. JPMorgan’s balance sheet might then appear at least partially hedged in the Basel III sense of the word.

Under the authority of the Chief Investment Office (CIO)—and outside of the trading unit—a trader in JPMorgan’s London office assembled a relatively limited number of over-the-counter credit derivative contracts tied to two primary index groups: the CDX, a group of North American and Emerging Markets indices, and the iTraxx, a group of European and Asian indices. While the initial number of contracts appears small, the notional amounts grew large as more contracts were added. Frequently, instead of disposing of troubling positions, new over-the-counter derivative contracts were added to the balance sheet.

Once profits started to roll in, the trade’s intended purpose seemed to have changed. Initially intended to hedge against bank credit risk, it was instead the profits that got attention from the traders as well as from managers as far up as JPMorgan’s Operating Committee. And then, when markets changed and illiquidity set in, the focus switched to loss avoidance. That incentive became so powerful as to be a corrupting force that changed the team’s actions and apparently their intents. As documented by the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), laws were broken at the same time that losses mounted.

MISSED WARNINGS

Who was to blame for the scandal? The short answer is that the entire management team was responsible. Yet there were aspects to the portfolio that should have sent warning signals, especially to management accountants.

The contracts resulted in a net short position, meaning the hoped-for gain could only be generated from a market downturn. Regulators have viewed shorts as inherently risky, particularly when derivatives are used, and the accounting rules are biased toward that view.

Accounting rules require extra disclosures for credit contracts. But the positions in the London Whale trade were presented as an overall adjustment to the JPMorgan portfolio rather than specified transactions. In U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), short positions rarely, if ever, qualify for the special accounting used to portray plausible and successful hedging. Such special elections remain transaction based, not portfolio based—in contrast to the greater flexibility provided by International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). But JPMorgan was bound to abide by U.S. GAAP, even for its London activities.

Indeed, the contracts couldn’t be placed in a special hedge accounting election. They were held in the required default accounting format for derivatives. As a trader might describe it, they were marked to market. In other words, the fair value of the contracts was placed on the balance sheet and then measured again for every subsequent date the balance sheet was issued, with the change in value (the mark) posted to current earnings. This is the same accounting treatment for trading positions in most broker-dealer activities.

It became something of a specialized case where the measurement rules were misapplied. There should have been some concerns raised at JPMorgan—perhaps by management accountants—when these positions became noticeable as a source of profits.

UNCHECKED ACTIONS

The trade was executed and managed from JPMorgan’s -London trading office. The Chief Investment Office desk responsible for the position reported to a local, London-based manager. And the trade was the responsibility of a single trader, supported by an assistant trader. The growth in the volume of contracts, among other things, suggests that the CIO trader acted with unusual autonomy. The timing for an autonomously minded trader was good because the trades were initiated at about the same time that the bank CEO, Jamie Dimon, stepped back from day-to-day risk management.

Initially, the trade was executed and managed without a set trading limit (i.e., there wasn’t an established maximum gain or loss allowed in any one trading session) and without oversight from an independent risk manager. The marks to the position were reported in earnings but weren’t frequently subjected to independent confirmation.

This changed when losses appeared and continued to mount. After the markets changed and losses piled up, far more formal best practices procedures consistent with JPMorgan’s reputation were imposed. By then, however, the losses had become unavoidable.

A GAMBLER’S MIND-SET

The strategy to increase the size of the positions is typical of a gambler’s mind-set. Faced with losses, the trader took the view that markets might rebound in his favor. To recover his losses and advance his portfolio’s profitability, he increased the size of the bet. It was more the action of a risky gambler than a risk manager or a rational, systematic proprietary trader. It was the opposite of hedging his bet.

When the losses continued, a liquidity problem emerged. The market was willing to sell the trader more of what he already held but was much less willing to buy back the product. The trader was stuck with his position.

As the positions grew, the larger size was accompanied by larger losses and declining liquidity. This particular trend should have made JPMorgan’s management accountants wake up and take notice. Since the derivatives were over-the-counter, they were also subject to the complex and enhanced disclosure rules under Accounting Standards Codification® (ASC) Topic 820, Fair Value Measurements and Disclosures. The appropriate fair value for reporting would be the most representative point within the bid-ask spread in a hypothetical transaction for a comparable contract. As markets became less liquid, the traders relied increasingly on the accounting method of setting the fair value to the mid-market price within a bid-ask spread, as permitted under ASC Topic 820.

But a more aggressive mark within the bid-ask spread was used for the fair value statistic, infecting JPMorgan’s books and records. Using aggressive marks seems to be an effort to falsely minimize reported losses. The situation worsened. Ultimately, the marks were placed outside the bid-ask spread that could be documented, and, in one period alone, the mark-to-market losses in the portfolio were understated by more than $660 million on a pre-tax basis.

Weaknesses in internal controls masked these events. Under SOX, management is required to certify the adequacy of internal controls designed to support the reliability of financial statements. The JPMorgan CIO had a unit called the Valuation Control Group (VCG) that was tasked with independently assuring that traders reported the value of their positions accurately pursuant to written policies. But VCG policies were rewritten during the course of the crisis. The VCG was unequipped to cope with the trader’s portfolio and didn’t function as an effective internal control. It was understaffed, insufficiently supervised, and didn’t adequately document its actual price-testing policies. The actual price testing also was subjective and insufficiently independent from the traders, who influenced the process.

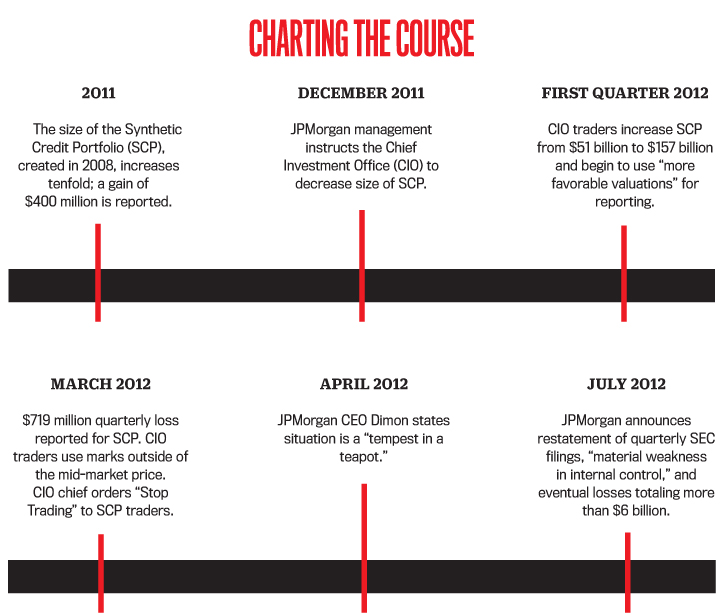

Eventually, when the extent of the failure was uncovered, JPMorgan moved the positions out of the CIO to its trading unit. Several individuals in the CIO lost their positions, were exposed to compensation clawback, and are subject to continued legal action. And JPMorgan restated its quarterly SEC filings.

WEAK LIQUIDITY

When senior management finally realized what was going on, they made significant attempts to correct it, even instructing at one point for the liquidation of the CIO’s entire position. But the market couldn’t liquidate such a large amount in a single trade or even over a short period of time. Management seemed comfortable with the size of some positions, even if they “represented the equivalent of 10-15 trading days” in that particular group of instruments. At another point, the liquidation of a part of the portfolio would have taken nearly two months, not the “snap action” expected.

Counterparts began requesting additional collateral from JPMorgan, calling into question its valuations to the tune of more than $500 million. The value of the collateral requested doesn’t always track the fair value of the contracts, especially as market prices change and markets become stressed and illiquid. But such collateral disputes weren’t a good sign for the validity of JPMorgan’s own valuation process. While collateral disputes don’t necessarily signal fraudulent valuations, the disputes do invite an increase in the scrutiny used to oversee the bank’s valuations. In this case, those disputes represented the tip of the iceberg. Valuation discrepancies discovered in spreadsheets compounded the trading problem. One such item contained a loss understatement of more than $200 million.

A telltale sign of the coming scandal was that the London Whale’s assistant trader maintained two sets of books. One set was for external reporting. The other was kept at the trading desk, allowing the small CIO team to track the difference between reported and reliable prices. At one point, the unreported difference was perhaps higher than $750 million. The lack of liquidity in the positions forced JPMorgan to take more time executing a liquidation. During that time, however, losses rose from $2 billion to $6 billion, and investigators were able to gather the information that forced the SEC to deliver its punishing judgments.

WORLD’S TOP RISK MANAGER TUMBLES

To JPMorgan, this seemed to be a survivable storm. As described in the Congressional investigation into the scandal, in 2012, “bank management [decided] to reduce the [specialized portfolio], but instead, over the next three months, [it] exploded in size, complexity and risk.” On March 23, 2012, the head of the CIO ordered trading to stop. On April 13, 2012, CEO Jamie Dimon called it a “tempest in a teapot.” The Whale’s losses initially seemed manageable to senior management because of the company’s size and overall performance. While aggregate losses reached $6 billion, they were stretched out over time. Further, the bank’s size made the losses appear relatively tame and not a franchise-destroying threat. JPMorgan asked investors and regulators to believe that the bank remained strong enough to absorb the loss given the company’s $1 trillion balance sheet. The company still had sufficient regulatory capital even after the losses.

But Dimon and the board of directors were duped. Relevant information wasn’t sent up the chain of command. Faulty information was transmitted, and information access was limited for both senior management and the board.

Dimon had earned a global reputation as the industry’s top risk officer. The market had come to expect that every day, almost immediately after the market close in New York, Dimon was supposed to receive a report about JPMorgan’s daily value at risk (VAR)—the market value its entire balance sheet might lose if the market swung against it by a set probabilistic shift.

Despite this culture of daily VAR reporting, JPMorgan’s trading positions weren’t subject to traditional trading limits or standard risk analysis. The London traders even lengthened their trading day to the New York close, hoping that the American market’s closing prices would be kinder to their profit and loss (P&L) than the London close. It was still a daily 4:15 p.m. VAR reporting approach, but now the flawed reporting extended to time zone choices! As if that weren’t enough, valuation models were changed in a manner reminiscent of a Freddie Mac transgression caught by the SEC years before, where valuation models were tweaked to enhance reported profits or limit posted losses.

TWO MAJOR BREAKDOWNS

For the SEC, the eventual losses in the Whale trader’s positions reflected two major breakdowns under securities laws: a breakdown in internal controls and a failure to apply the fair value measurement rules properly.

The first breakdown resulted in an unprecedented SEC action related to internal controls. The failure to maintain internal controls constituted violations of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and various parts of SEC Rule 13a. On September 19, 2013, SEC Co-Director of the Division of Enforcement George Canellos announced that JPMorgan agreed to admit wrongdoing after the SEC pursued fraud charges against former JPMorgan traders. The SEC said the traders exploited massive shortcomings in JPMorgan’s internal controls.

The second major breakdown involved improper application of the fair value measurement rules, an accounting failure. The positions assembled in the CIO were derivatives. The accounting for them under U.S. GAAP is governed by the rules contained in ASC Topic 815, Derivatives and Hedging, and ASC Topic 820.

On each reporting date, each contract was to be measured at its fair value and recognized as an asset or liability on JPMorgan’s balance sheet. Changes in fair value from the prior reporting date were to be recorded in the earnings section of the continuous Statement of Comprehensive Income.

Because of the nature of the strategy, the CIO’s positions didn’t qualify for special hedge accounting. That special election may have either provided an earnings offset to the positions’ gains and/or losses or permitted the deferral of their gains and/or losses in accumulated other comprehensive income, subject to future reclassification to earnings. In any event, special hedge accounting didn’t apply.

AVOIDING FUTURE SCANDALS

The lessons of the JPMorgan scandal go beyond internal controls and fair value measurement. Good corporate governance, use of best practices, and the tone of diligent, proper oversight—with that tone set at the top—could have averted this crisis. Major warning signs and disconnects must be recognized for what they are and chased down. When a risk management center gains a reputation as a profit center but has none of the traditional profit center controls or practices, eventually something will go amiss.

It becomes difficult to apply those principles in the face of profitability. When things are going well, often no one looks for problems. Why should they? Everything feels fine. But companies should be on guard at all times for such problems—especially in the context of a publicly traded financial institution—because various laws require such management diligence.

When overall profitability is high, such problems may not appear on the official radar, or they may be ignored because any associated losses are absorbable. But this can gradually fester until losses grow and become both significant and irreversible.

The proper tone at the top and the diligent application of existing rules—from internal controls to accounting rules—are the powerful tools that management accountants are asked to apply. The diligent management accountant can use these tools to defeat human bias, errors in judgment, or worse. And that’s what most people expect of management accountants as reliable and empowered guardians at the gate.

April 2015