Low unemployment and increased demand for skilled labor has made it more difficult for companies to attract and retain talent. As a result, companies have had to increase their emphasis on developing the employees they already have. In the current business environment, the traditional model of providing annual performance evaluation fails to provide the timely feedback necessary to ramp up employees’ skills quickly enough. In addition, many companies have noted that the traditional annual review process requires a tremendous amount of time and effort, and the results aren’t worth the high cost.

Today’s employees also show a strong preference for more frequent feedback than the annual performance review provides. Millennial employees, who are now the largest generation in the workforce, want to be coached and mentored at work. They prefer more frequent feedback than their older counterparts. An annual performance review simply doesn’t provide the feedback that Millennials seek, which may contribute to the increased likelihood of job-hopping by today’s employees.

BENEFITS OF TECHNOLOGY

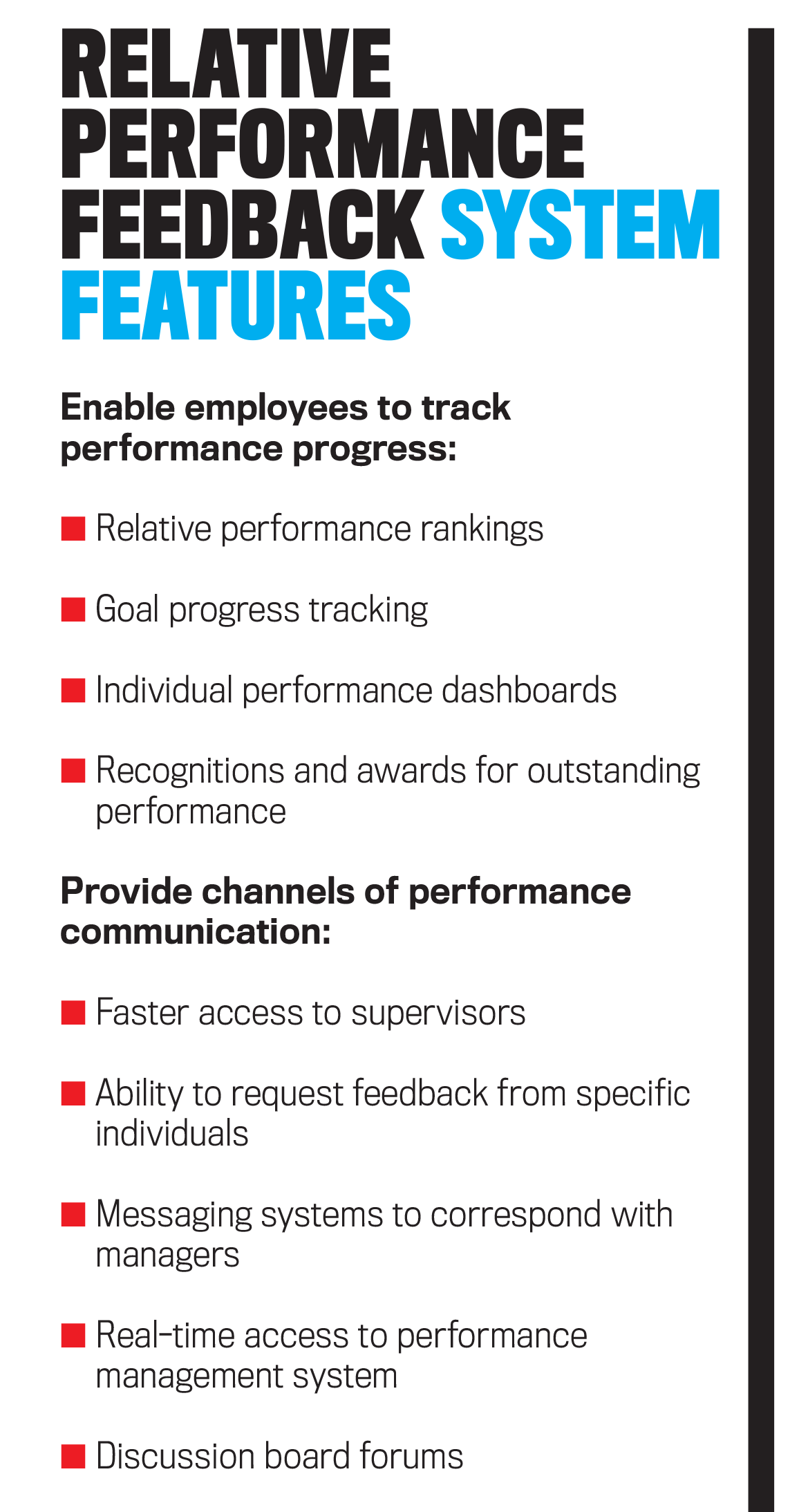

Formal performance evaluations require substantial time, data, and paperwork, which may explain why formal feedback has historically been so infrequent. Improved technology can now aggregate, analyze, and disseminate performance information with relative ease, dramatically decreasing the cost of providing frequent feedback to employees. As a result, many notable companies have developed performance evaluation systems that provide more frequent feedback. GE’s new system, PD@GE (PD stands for performance development), is an interactive mobile app designed to provide constant feedback about employee performance. It provides employees with a list of goals they should be working on and allows employees to request feedback and guidance from their supervisors at any time.

Goldman Sachs has adopted an online feedback system that provides employees with directives for improving their work rather than a year-end evaluation. Their system also allows for the solicitation of feedback from a supervisor at any time. JPMorgan Chase’s Insight 360 software allows subordinates and supervisors to review one another in real time rather than at the end of each year. These companies are joined by others such as Accenture, Facebook, Virgin America, HP, LinkedIn, LivingSocial, and 1-800-Flowers.com that are all seeking ways to provide more timely feedback in order to improve the development and performance of employees. What’s more, several workplace software systems, such as work.com or Workday, are readily customizable and have allowed smaller companies to increase the frequency of employee feedback by meticulously tracking and aggregating performance feedback.

Software companies such as Badgeville take frequent performance feedback a step further by working with businesses to “gamify” the workplace. In a gamified environment, companies use employee performance metrics such as sales or production targets to keep an ongoing score of how workers are performing relative to other workers and to prod the workers to improve. Management’s use of frequent feedback is at the heart of these enhanced competitive work environments. These systems continuously display an employee’s performance position on dashboards and scoreboards, making performance feedback highly visible to all employees. In gamified workplaces, what was once a job to be done has become a game to be won.

Given the changing needs of companies and employees as well as improving technology, the shift to more frequent feedback is logical. But very little research has examined whether more frequent feedback actually improves performance or which factors make frequent feedback effective. We conducted a research study to provide evidence on these issues. First, we examined whether more frequent feedback leads to better performance. We focused on a particular type of feedback—relative performance feedback—as new workplace software systems can provide this type of feedback with little or no intervention from managers. Second, our review of workplace feedback systems indicated that while many companies are providing more frequent feedback, some companies provide this feedback at the employee’s request and other companies present feedback without employee solicitation. So we were also able to examine the impact of employee choice on feedback effectiveness.

RELATIVE PERFORMANCE FEEDBACK

Relative performance feedback, or reviewing how an individual’s performance compares to that of others, is a useful management tool that can motivate employee effort. Companies use relative performance information to track and compare employees’ productivity on a number of dimensions, such as billable hours, sales, production, or customer satisfaction. Relative performance feedback motivates employee effort because it introduces social comparisons by making employees aware of how successfully they’re completing their jobs relative to other employees.

Because employees can be competitive and driven to achieve (or, at the very least, don’t want to look bad compared to their colleagues), relative performance feedback can motivate and encourage employees to improve in order to meet and exceed the performance of their peers. Although academic research such as “Private and public relative performance information under different incentive contracts” in The Accounting Review by Ivo D. Tafkov in 2013 has generally shown that relative performance feedback is an effective tool to boost employee effort and job performance, providing such information on a frequent basis has until recently been too complex and time-consuming. That’s no longer the case thanks to modern management information systems, cloud computing, and the accessibility of information across multiple, convenient devices.

CHOICE AND MOTIVATION

Managers have discretion over how often to provide feedback or whether to allow employees to solicit feedback as desired. Research has shown the choice to request feedback may have a strong impact on how effective feedback ultimately is to future performance. Individuals place more weight on information they choose to receive than they do on information that’s provided without their explicit request—a phenomenon called the “information choice effect.”

For example, one 2001 study, “The beguiling pursuit of more information” in Medical Decision Making by Donald A. Redelmeier, Eldar Shafir, and Prince S. Aujla, found that practicing physicians are more likely to account for patient information when they choose to acquire the information compared to physicians who are simply provided identical information without their explicit choice. Likewise, we expect that when employees seek out relative performance feedback of their own accord, they’re more likely to internalize and respond to that feedback.

The act of choosing when to view relative performance feedback is also motivating because it satisfies an individual’s need for autonomy, which increases intrinsic motivation. Thus, we expected that if individuals chose to view relative performance feedback, their performance would increase as they received more frequent feedback. By comparison, when individuals are unable to choose whether or how often they receive relative performance feedback, the lack of control can result in lower intrinsic motivation. In this case, we expected that more frequent feedback would be less helpful to future performance.

EXPERIMENT AND RESULTS

We recruited 449 participants from business classes at two large public universities to take part in our study. During the experiment, participants had to analyze market conditions and decide how much of a fictitious product they needed to produce in order to maximize profit. Following each of the 12 trials in our experiment, we created a simplified report containing relative performance feedback by comparing participants’ performance with that of their peers.

Participants in the “assigned frequency” group were provided this feedback at various predetermined relative performance feedback frequencies (e.g., some received feedback after every trial, after every four trials, or after all trials were concluded). The remainder of our participants were in the “choice of frequency” group and were able to choose after each trial whether or not to receive the relative performance report. We then analyzed how feedback frequency affected performance in subsequent trials.

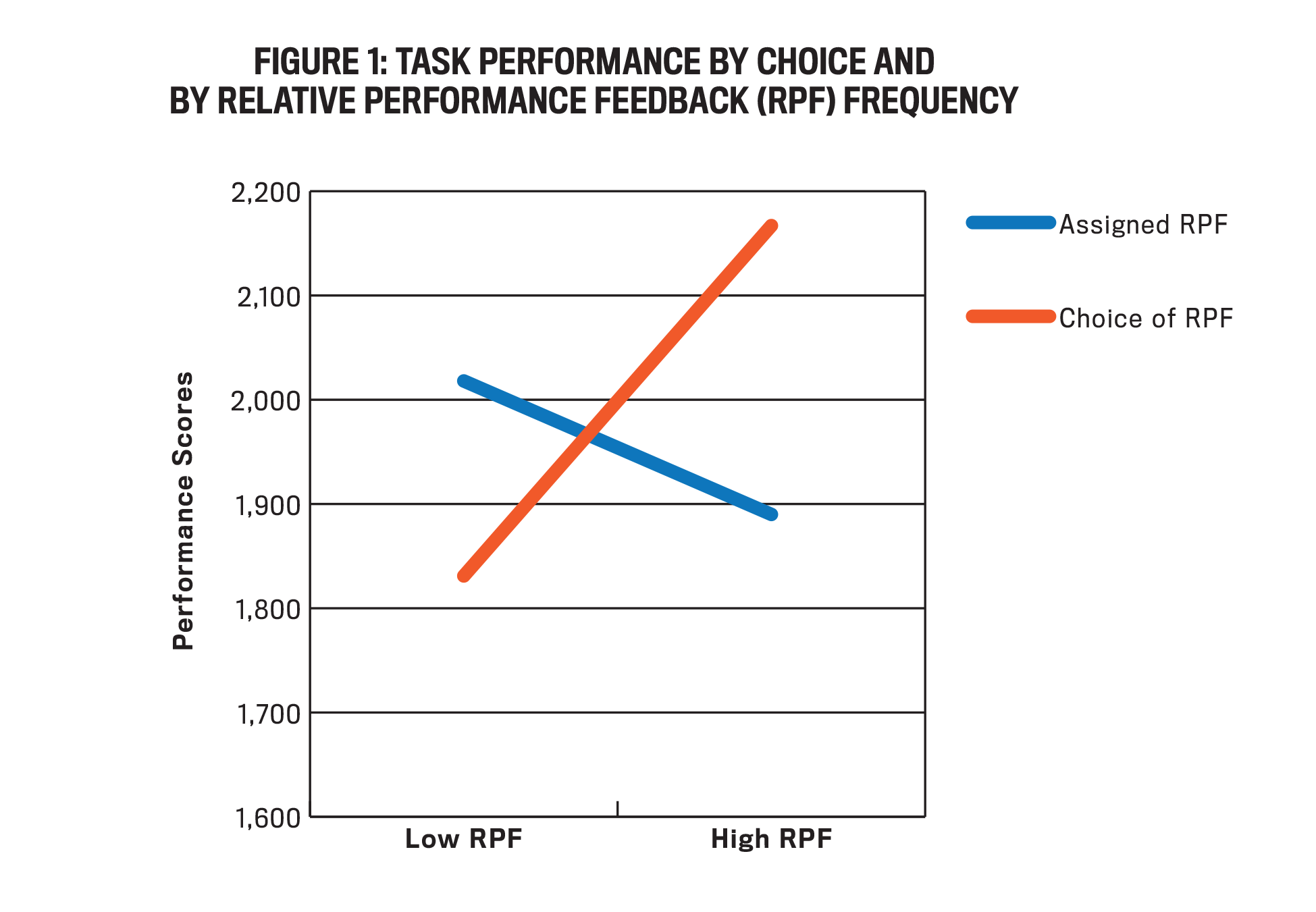

Interestingly enough, the effectiveness of relative performance feedback is highly dependent on participants’ ability to choose to receive feedback. For participants who were able to choose when to receive relative performance feedback, increased feedback frequency resulted in increased performance. In contrast, we found evidence that the forced feedback actually decreased performance for participants who were assigned to receive relative performance feedback.

To help illustrate the effect of feedback frequency on performance, we compared individuals who received relative performance feedback after every round to those who only received relative performance feedback at the end of the task (see Figure 1). For those participants allowed to choose the frequency of relative performance feedback, greater frequency benefited performance. Specifically, those who chose feedback every trial outperformed those who received it at the end of the task by 16%. In contrast, for those assigned to receive relative performance feedback, greater frequency hurt performance. Those who were assigned to receive feedback after each trial underperformed those assigned to receive feedback at the end of the task by 6.8%.

While our results show that choosing the frequency of relative performance feedback was key for improved performance, we also wanted to understand how feedback led to improved performance. Relative performance feedback tells individuals how well they’re performing compared to others, but unlike other types of feedback (for example, when a manager sits down and explains sales techniques), the feedback doesn’t provide any direct information that indicates how individuals can perform a task better.

From our results, we learned that relative performance feedback can serve as a check on the effectiveness of someone’s performance strategy. In other words, relative performance feedback is helpful not because it tells you the ideal strategy to be successful, but because it tells you whether your current strategy is working. We found that when participants were performing well relative to peers, there was little change in their strategy for making production choices over the 12 trials. In contrast, when participants chose to receive relative performance feedback and saw that they weren’t performing well relative to their peers, they were more likely to change their strategies in future trials, which resulted in higher performance.

Yet relative performance feedback only appeared to improve the strategies of poor performers who had the choice of whether to view relative performance feedback and actively sought it out. For poor performers who were forced to receive disappointing information regarding their relative performance to peers, it was demotivating and didn’t lead to improved performance.

BENEFITS AND CAUTIONS

Our study highlights several useful applications for management practice. From a practical perspective, it sheds light on the efficacy of providing relative performance feedback in the workplace. The propagation of popular software systems that facilitate frequent collection, analysis, and distribution of relative performance feedback appears capable of providing significant benefits to employees. Our findings suggest, however, that these benefits are contingent on employees’ ability to choose how often they receive relative performance feedback.

Furthermore, the adoption of such systems may even backfire if employees are mandatorily provided relative performance feedback. According to our results, although companies may have the ability to provide frequent relative performance feedback, forcing feedback on employees may be detrimental to performance. The findings underscore the importance of having individuals choose how often to receive relative performance feedback and suggest that companies can benefit by taking advantage of technology that provides employees with the ability to choose when to receive it.

Just because the information is now readily available with modern management information systems doesn’t mean that it should always be provided to employees. Fortunately, several software programs with the capability for employees to request information as desired already exist. To get the most out of feedback systems, companies will have to determine ways to encourage their employees to seek out relative performance feedback.

February 2019