Meeting index investors’ information needs requires changes in financial reporting. Passive investors, who now control and vote 30% of all U.S. shares, care more about long-term governance practices than short-term financial metrics. These investors don’t trade shares when accounting balances fluctuate. Accounting topics like revenue recognition, lease accounting, and credit impairment matter little to owners like these with a long-term view.

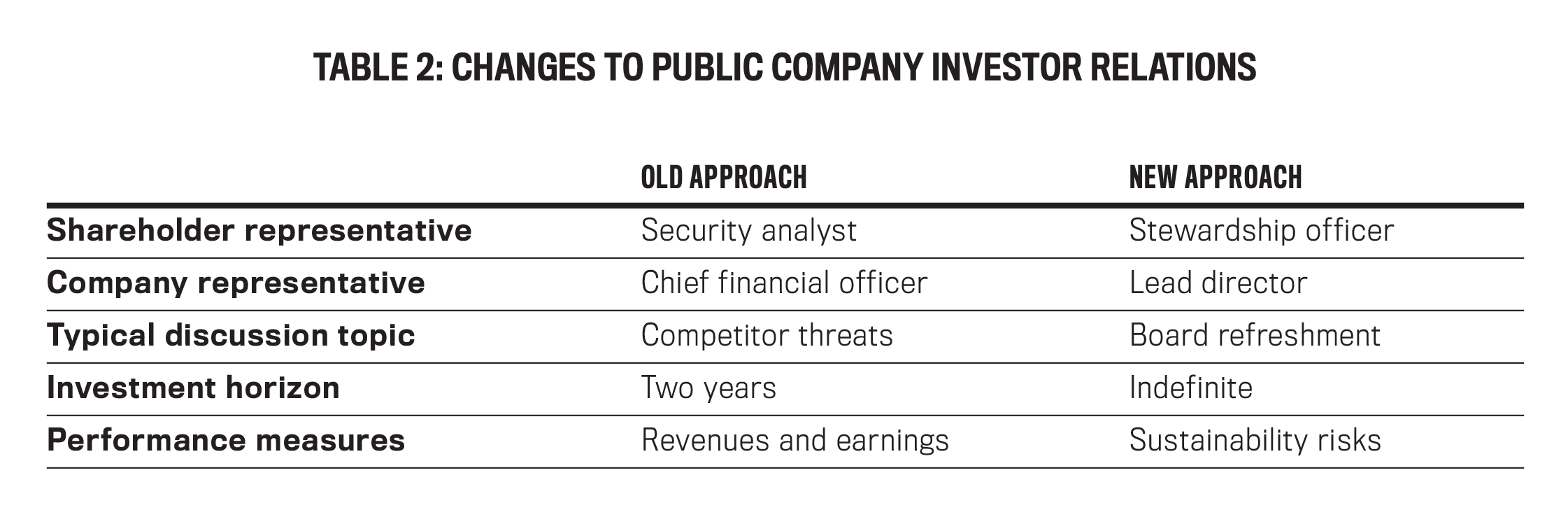

Listed companies that want to develop deep relationships with this group of owners must move away from an investor relations model in which CFOs offer analysts revenue or earnings guidance to a model based on independent directors discussing board refreshment, sustainability, and compensation with stewardship officers. Companies will have to modify their reporting practices if they want to meet the needs of these increasingly important investors. This new approach is another step in the long evolution of financial reporting that first emerged in the wake of the U.S. Civil War. Let’s take a look at how we got to this new environment.

HISTORY OF FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING

With the Civil War over, the United States was growing, expanding west into vast territories. Railroad companies needed enormous amounts of capital to lay straight, level tracks across North American rivers, valleys, forests, plains, and mountains. Wealthy British investors were willing to fund this expansion if they felt comfortable that they would get their money back. The disclosure of financial reports helped provide that comfort.

Over the next half-century, agreed-upon ways to communicate financial position and results emerged among executives, investors, auditors, and government officials. In 1934, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd published Security Analysis to explain how investors could use these reports to make money. The analysis of corporate financial statements permitted comparison between a security’s market price and its “intrinsic” value. Astute investors could get rich if they bought stocks trading below intrinsic values and sold when the stocks became overvalued.

Four years later, economist John Burr Williams’s The Theory of Investment Value introduced the technique of discounting future cash flows to calculate intrinsic value. All modern finance textbooks cite this method when discussing asset valuation.

In the early 1970s, Robert Trueblood, chairman of Touche Ross, chaired a committee (the Trueblood Committee) to explore the objectives of financial statements. The resulting report extended Williams’s work and argued that accounting reports should be designed to allow investors to predict the amount, timing, and certainty of a company’s future cash flows. This idea became the central idea in the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s (FASB) Conceptual Framework, the foundation for U.S. financial accounting rules.

Also around this time, a group of economists studied the relationships between stock prices and accounting balances. Statistical analyses showed that security prices adjust quickly to earnings releases. Eugene Fama argued that it’s very difficult for investors to beat the market with financial analyses of accounting reports. This reasoning became known as the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH).

While no one believes that financial markets are perfectly efficient, experienced investors agree that they are competitive. Not even Warren Buffett beats the market every year. In 1976, John Bogle, reflecting on implications of the EMH, sold shares in the world’s first index fund with a portfolio designed to match the returns of a stock market index.

INFLUENCE OF INDEX INVESTING

Today, the vast majority of assets held by U.S.-registered investment companies are in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Both investment vehicles pool investor funds to buy portfolios of securities. Mutual funds sell fund shares directly to investors, and fund managers stand ready to buy back shares at prices calculated after the close of each trading day. Shares in ETFs are sold through brokers and traded on security exchanges at prevailing market prices. A mutual fund and an ETF holding the same basket of securities deliver similar returns.

Some mutual funds and most ETFs hold portfolios of securities designed to mimic the financial return of a market index (such as the S&P 500 or Russell 2000) or a particular sector (like healthcare or oil and gas). Assuming that the median investor earns the same as the market returns, passive investing should outperform half of all active money managers within a market or sector. After considering the low operating expense, since it doesn’t cost much to buy and hold a basket of securities, passive portfolios produce above-average net returns.

The benefits of index investing have attracted widespread interest in recent years. According to Moody’s, about 30% of all money invested in U.S. mutual funds and ETFs is passively managed (http://bit.ly/2sr4QLa). The two largest money managers in the world are now BlackRock, the leader in ETFs, and Vanguard, the leader in index mutual funds.

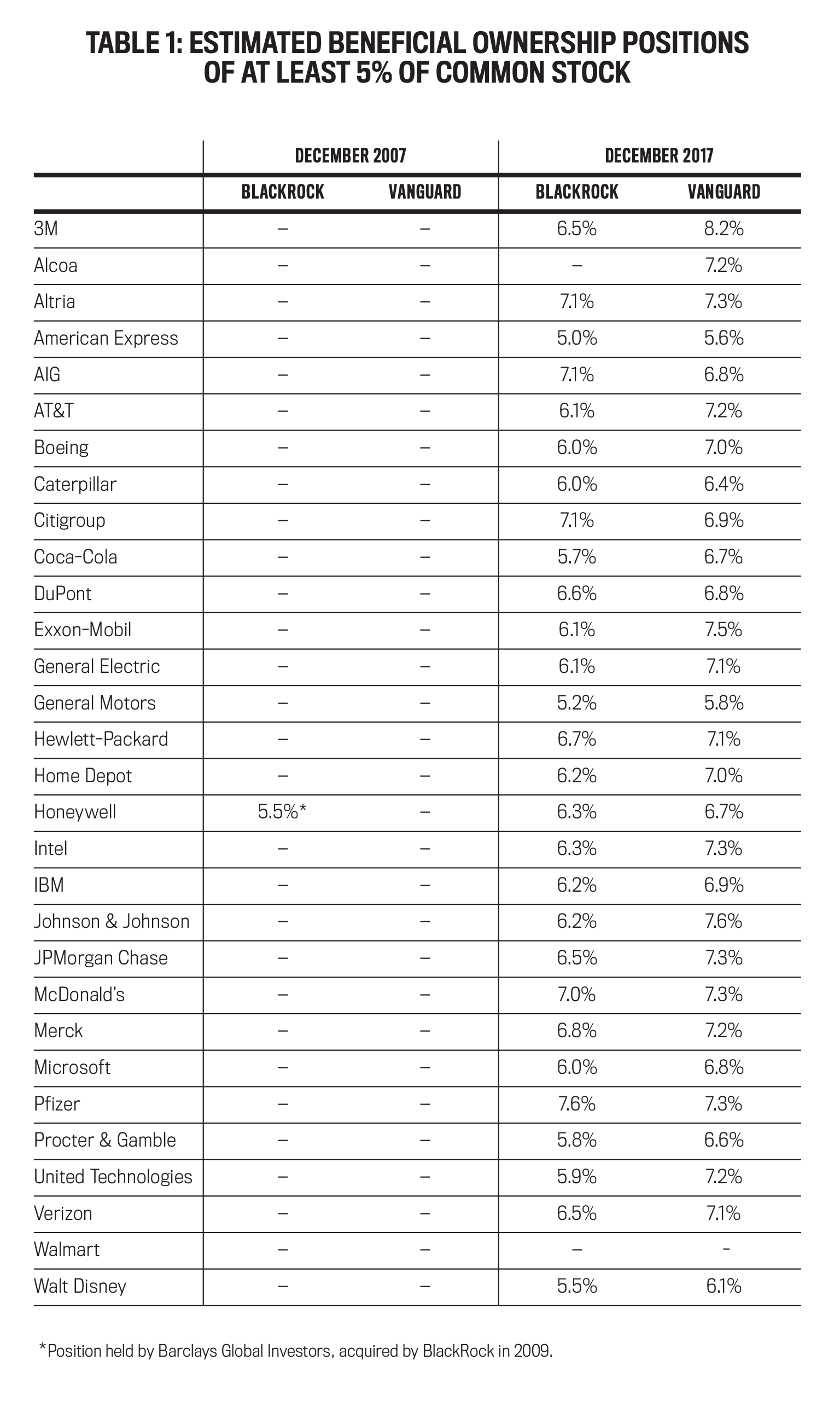

Annual proxy filings made by public companies with the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) provide evidence of the rising influence of these two money managers. Listed companies in the U.S. are required to identify investors who hold more than 5% of the company’s outstanding common stock and report these ownership positions in annual proxy statements. Money managers are classified as beneficial owners because they use client money to pay for security purchases.

Table 1 shows the beneficial ownership positions greater than 5% of the common stock held by BlackRock and Vanguard in the 30 companies comprising the Dow Jones Industrial Average as of December 2007 and December 2017. These two money managers, respectively, accumulated at least 5% of the common stock of 28 and 29 of these companies over the past decade.

Index investors seek to deliver investment returns that mirror market indices. As long as an equity is in a benchmark index, passive investors have an incentive to buy and hold that stock. Failure to hold onto the stock brings unwanted tracking errors, where the portfolio results stray from that of the underlying index. A passive money manager’s investment horizon lasts as long as a security is part of a broader index. Trading decisions don’t turn on the disclosure of traditional accounting information such as a quarterly earnings release.

THE IMPORTANCE OF GOVERNANCE

This approach means passive money managers have a different set of concerns than other investors. They can’t sell shares when bad news surfaces. As long as a company’s stock is in an index, a passive investor must hold those shares regardless of recent financial performance. As a former Vanguard CEO argued, index investors are permanent shareholders who hold onto a stock whether or not active investors pile in or run for the exits.

This inability to sell diminishes the usefulness of accounting information to value securities. Instead, index investors use accounting information to assess the governance practices of companies in their portfolios. What matters most is the quality of the board of directors. Skilled directors guide executives and replace weak CEOs.

Evidence that high-quality directors add value can be found as far back as the beginning of the 20th Century. In “Did J.P. Morgan’s Men Add Value? A Historical Perspective on Financial Capitalism,” J. Bradford De Long writes how the presence of a J.P. Morgan banker on a company’s board in the years preceding World War I was associated with 30% higher stock valuation arising from better operating performance. (See Inside the Business Enterprise: Historical Perspectives on the Use of Information, edited by P. Temin, University of Chicago Press, for more.)

Governance is about the long game. If owners elect good directors, then a company is positioned for long-term success. Skilled directors hire effective CEOs who recruit strong executives who adjust operations as customers and tastes change, patents expire, laws evolve, innovations emerge, and competitive advantages fade. These adjustments allow a company to deliver profits year in and year out. Figure 1 shows the long-term logic of good governance.

My interviews with stewardship officers at three leading index investing firms, quoted throughout the article, revealed this reasoning. Said one person:

“We’re neither interested in nor capable of micromanaging the affairs of any company in our portfolio. When things go awry, one of the things we fall back on as investors is the ability to effect change at the board level.”

To go awry means a company reports results that consistently lag performance figures posted by peer companies. Stewardship teams then ask to speak with directors to understand how that company’s board functions. These discussions, known as engagement, aren’t deep dives into how companies are run:

“It’s not about getting into the weeds of the company at all. We don’t do that here. We’re not expert enough to do it. The management and the board ought to know a whole hell of a lot more about a company than we would ever know.”

Instead, conversations revolve around how boards facilitate corporate renewal. Getting good people into boardrooms accomplishes many things:

“When you get the right people on the board—experienced, engaged, well-informed people in the boardroom—who appoint management who are equally engaged and skilled, then the governance process will deal with any concerns. We are very unlikely to need to talk to those companies.”

If results of engagement discussions suggest that weak governance contributed to lagging performance, then passive investors use their voice (influence from holding sizable equity positions) or vote (proxy ballots to vote against nominated directors) to bring change to a board’s nominating, audit, or compensation committees.

Nominating Committee. The nominating committee recruits new directors. Good governance rests on attracting directors who can provide effective oversight as companies and markets evolve. A red flag is a board composed of long-tenured directors with similar backgrounds. The poor showing of banks during the 2007-2009 global financial crisis illustrates how many boards failed to attract engaged directors with derivatives and risk management expertise. Talented directors help executives anticipate and respond to problems.

Strong board members with relevant industry expertise are able to evaluate company performance and gauge long-term threats. Great directors have deep industry knowledge and offer productive suggestions for long-term renewal. If things go very badly, these directors protect investors by replacing the CEO or selling the company at a fair price. To assess board strength, stewardship officers seek information on how nominated directors will be expected to contribute when foreseeable problems arise.

Engagement efforts also seek to determine how a nominating committee refreshes the board of directors. Refreshment means attracting qualified new directors, managing the performance of current directors, and ensuring that tenured directors leave at appropriate times. Of particular concern is whether boards bring diverse perspectives to the table. Representatives of each of the passive companies I interviewed look for the presence of women directors to gain comfort that deliberations consider the perspectives of both genders.

Audit Committee. The audit committee seeks to keep a company’s financial reports free of material misstatement. Traditional audit committee work includes selection of the independent auditor and review of critical accounting policies. The most famous breakdowns in such oversight were WorldCom (deferring operating costs instead of charging them against income) and Enron (marking illiquid investments at implausible valuations and keeping sizable amounts of debt off the balance sheets). Misstatements impair investors’ ability to value securities.

The selection of a particular accounting treatment represents a secondary concern to passive investors. Since passive investors won’t sell a holding even if it becomes overvalued, short-term movements in security prices have few consequences. Any conceivable difference will reverse over a 25-year investment horizon. What does matter to these investors is the identification, measurement, and disclosure of long-term risks facing the company. Said one individual:

“I want to make sure that a company has a plan which incorporates sustainability in the long-term strategy.”

Sustainability means a company has the ability to pursue business goals indefinitely. Operating activities with harmful social consequences (such as emitting pollutants, paying unfair wages, selling unhealthy products, or bribing government officials) threaten the long-term earnings power of a company. In this context, sustainability isn’t about taking the moral high ground but viewing future business activity through an economic lens. Stewardship officers see sustainability issues as strategic financial risks to be mitigated.

If a company’s business model turns on the quality of its human capital, then stewardship officers want to know how the company assesses efforts to attract, motivate, and retain talented employees. The presence of diversity and inclusion programs or work-from-home initiatives mean little without comparing performance measures such as employee turnover rates or employee satisfaction survey results against previously established goals.

Compensation Committee. The compensation committee oversees incentives given to a company’s senior executives. Well-crafted pay plans contribute to the achievement of company goals. Stewards search for clear links between company goals, performance measures showing goal achievement, and rewards based on reported performance measures. High compensation should be associated with evidence of meaningful value creation, and the rationale for extraordinary pay decisions should be explained to shareholders.

Stewardship officers also look for directors to take ownership for the design and oversight of incentive programs. Another red flag is delegating this authority to management or a compensation consultant:

“When the chair of the comp committee can’t articulate the most basic tenets of the company’s compensation policy, or why they felt that this particular award or this particular metric or this particular level of achievement against the metric was incentive-worthy, and has to rely exclusively on the compensation consultant to answer the question, that’s a concern.”

IMPLICATIONS FOR FINANCIAL REPORTING

Passive investors care little about financial reporting efforts designed to help outsiders value the company’s shares. Information used to forecast the amount, timing, and certainty of a company’s earnings, cash flows, or dividends is of limited use.

Instead, these permanent investors seek to understand how decisions are made in the boardroom. To supply this information, listed companies must allow independent directors to answer open-ended questions posed by stewardship officers. Today’s investor relations practices—the CFO offering guidance to help security analysts build earnings models—permits calibration of share prices and revisions to buy and sell recommendations. Such activity does little for investors who have limited discretion over security selection. Table 2 compares the old approach to investor relations to what’s required to meet the needs of passive investors.

Should a company report lagging performance or exhibit some other governance concern, stewardship officers will want to meet directors, not company executives, to learn more about what happens in the boardroom. Many management teams are reluctant to let directors meet privately with owners. Executives worry that directors will run afoul of security laws that forbid release of material, nonpublic information.

Saying no to engagement requests, however, signals that executives believe directors don’t know enough about their company or may say something management doesn’t want investors to hear. Ignoring engagement requests brings the risk of brand damage (the company may be called out as unresponsive) or personal embarrassment (proxy votes may be cast against an unresponsive director at the next election). Management prohibitions against unsupervised conversations also signal reservations about a board’s quality. Effective financial reporting to passive investors requires that management teams prepare and allow independent directors to meet privately with investors.

Engagement meetings seek to determine if a board has the ability and willingness to hold management accountable for its actions. Conversations with management can’t provide this information:

“Talking to the management team about the board isn’t terribly instructive for us because I can’t think of a management team that’s said, ‘We have a crappy board, and you’re really lucky that things haven’t gone off the rails.’”

When given meetings with directors, stewardship officers look for evidence of independent thought:

“Every once in a while, we leave with a sense that either the directors are clueless or so under management’s thumb that we’re concerned.”

Productive meetings require directors to put away scripts and have candid conversations. Good directors are able to answer questions without jargon or violating selective disclosure laws.

Well-prepared directors should understand three things before meeting with stewardship officers. First, representatives from different organizations aren’t friends. These companies compete vigorously for client money and have distinct cultures and concerns. Index companies may challenge others’ views. For example, in its 2016 Annual Stewardship Report, financial services company State Street disclosed that it challenged the management of competitor BlackRock to better understand the role and responsibilities of BlackRock’s lead independent director.

Second, index investors aren’t activists. Activist investors typically acquire a sufficiently large ownership position to influence management to do something management wouldn’t do otherwise. This could include—but isn’t limited to—financial engineering moves designed to yield short-term returns. Paying a large special dividend, buying back stock, or selling a prized subsidiary are three examples. Index investors will continue to own a stock well after an activist has moved on to the next project. Activists’ recommendations that are expected to weaken long-term earnings power won’t secure indexers’ support.

Third, stewardship officers within a company may face conflicts of interest because different funds hold varied types of securities. For example, an asset manager may have distinct portfolios designed to match returns of large- and small-capitalization companies. Suppose a large company offers to acquire a small company, and the transaction requires shareholder approval from each company. If valuation of the target were deemed rich, a steward for the large cap fund would vote against the acquisition while a counterpart at the other fund would vote in favor. If the same fund held both companies, then the officer would have to sort through the conflict.

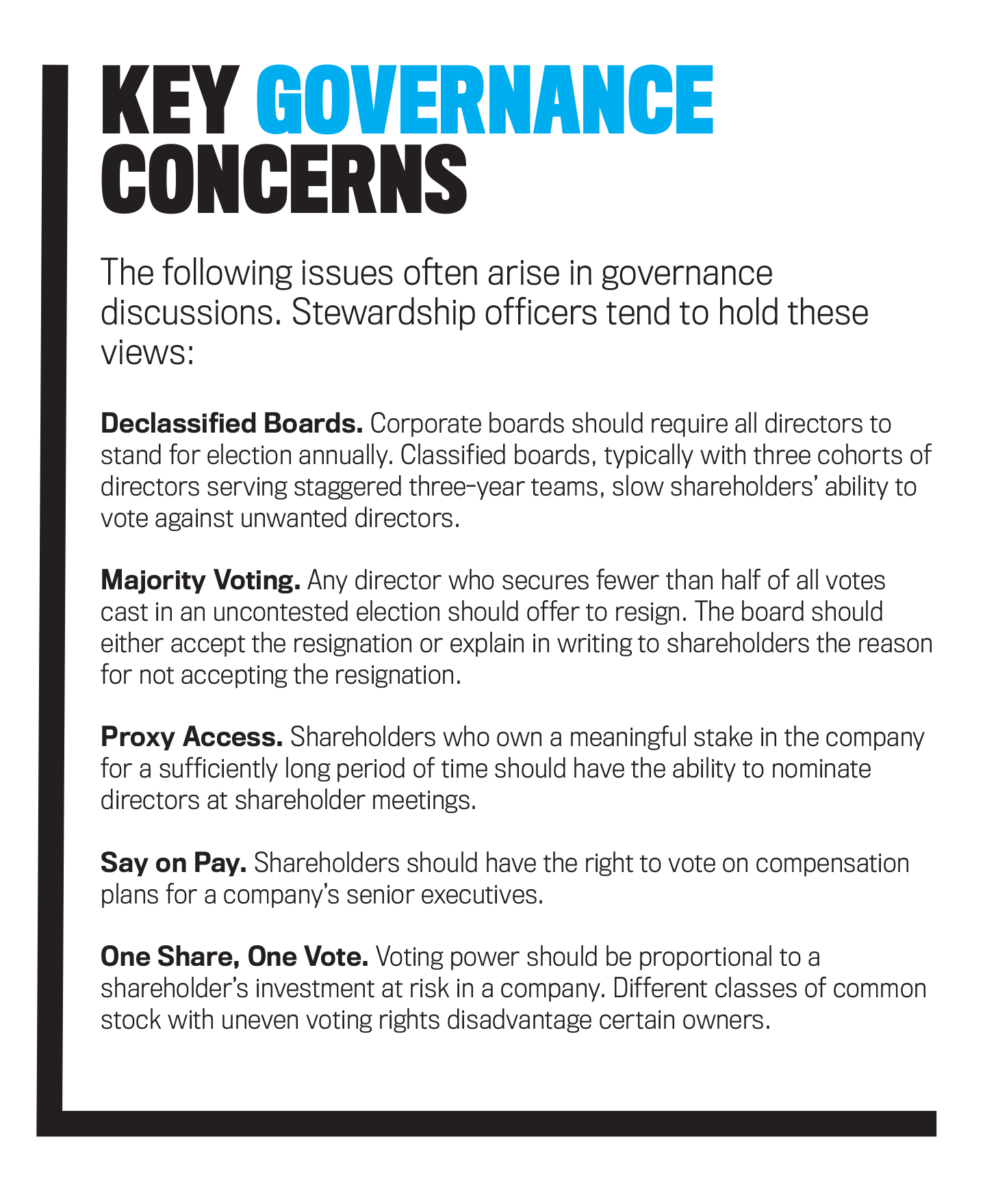

Most directors would likely prefer to avoid engagement discussions. Consistent, favorable financial results keep engagement discussions at bay. Yet every company stumbles. Engagement is almost inevitable for directors at large-capitalization companies within major stock indexes. Directors can mitigate the likelihood of engagement discussions by configuring a company’s corporate affairs to display sensitivity to shareholder concerns. “Key Governance Concerns” shows some of the issues that evoke reactions from many passive investors.

Boards should ensure that a company’s annual communication with shareholders includes a letter from the lead director that explains how activities of the nominating, audit, and compensation committees serve the needs of company owners. And if called upon to meet stewardship officers, directors should be prepared at a minimum to answer the sets of questions listed in “Key Engagement Issues.”

The rise of passive investing requires companies to modify investor relations practices to maintain good working relationships with permanent investors who aren’t swayed by the latest quarterly releases. Company communication with Wall Street should include disclosures about how boardrooms are filled with skilled directors who oversee effective CEOs. These activities will require active involvement from independent directors. The good news is that these discussions will likely support company efforts to manage for the long term.

February 2019