It’s no secret that much forensic accounting activity relies heavily on information provided by cost/managerial (CM) accounting systems. Yet the truth of this assertion can feel like a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it’s satisfying, even reassuring, to know that the information provided by CM accountants is of significant value to an essential and growing area of business activities. On the other hand, it’s somewhat sobering to know that explaining—and often defending—the CM information that we provide can be a difficult, even daunting, task.

THE VALUE OF FORENSIC ACCOUNTING

Forensic accounting as a separate and recognized discipline is a relatively new field that wasn’t well recognized until the widely publicized Enron fraud came to light. Nevertheless, the discipline has been functioning as an important cog in the business/legal community for decades. (For more on the evolution of forensic accounting, see “Forensic Accounting: Beyond the Courtroom” by David M. Shapiro in the September 2015 issue of Strategic Finance at http://bitly/2FkCUP0.)

A logical question from people who aren’t familiar with forensic accounting is “What does it encompass?” Although there are many different definitions, one that covers most aspects of the discipline includes:

- Fraud: detection, prevention, litigation, etc.

- Litigation support: accounting advisory services, including testifying in court, serving as an expert witness, etc.

- Business valuations: both adversarial and nonadversarial.

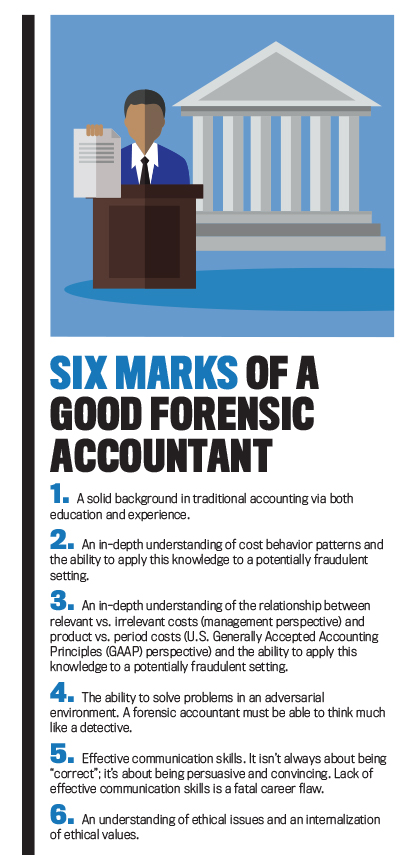

Accountants in general, and CM accountants in particular, are extremely valuable to the justice system because most attorneys, judges, and juries have little or no knowledge of accounting. Not surprisingly, virtually all cases revolve around money. The key question is “What is the appropriate, relevant, most accurate measure of the amount of money at issue in a particular case?” Whether the case is a civil case, a criminal fraud case, or some hybrid of the two, the resolution rests on the forensic accounting team’s estimated financial damages in the case.

In most cases, the forensic accountant doesn’t testify as to whether one side or the other is liable; essentially, the facts have to speak for themselves. Still, there are a number of situations where forensic accountants provide the court with important CM accounting information that goes directly to the determination of liability. But the measurement of damages typically requires a significant amount of accounting knowledge, much of which is the domain of CM accountants. Although virtually any area of accounting may be a component of a case, CM measurements are essential to the final analysis of damages. (An excellent resource that discusses the role and influence of the forensic accountant in depth is Forensic and Investigative Accounting by D. Larry Crumbley; Edmund D. Fenton, Jr.; G. Stevenson Smith; and Lester E. Heitger.)

THREE UNIQUE SCENARIOS

Given the great diversity of legal and financial issues that come up in litigation, no areas of accounting are immune. In fact, it’s common to have a situation in which there are questions about cost measurements, financial reporting, and tax consequences, all in one case. But the one area of accounting that’s common to virtually all civil cases is CM accounting. The following three real-world cases illustrate the nature and significance of CM in today’s litigation environment.

Case 1: Disputed Tax Credits

The Research and Experimentation Tax Credit (RETC)—also called the R&D tax credit—was enacted in 1981 to encourage U.S. businesses to engage in innovative research in an effort to make them more attractive to investors and to consumers who buy their products and services. But it took the U.S. Department of the Treasury several years to establish regulations that would allow financial institutions to utilize this law. After the regulations were in place, participating companies needed to devise a method of reconstructing the costs that qualified for the RETC for the years before the tax credit passed.

A large bank holding company applied for three years’ worth of RETCs, totaling nearly $30 million. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rejected all but about $3 million of the requested credits; in response, the holding company sued the IRS in U.S. Federal Tax Court. In order to prevail, it had to (1) show that the R&D projects identified for the credits in fact qualified under the law (an issue addressed by a computer expert from a leading university) and (2) show that the costs claimed for those projects were appropriate and were measured correctly (which was addressed by a CM forensic accounting expert from another top-rated university).

The Tax Court judge specifically charged the accounting/CM expert with providing the court with a logical framework for accumulating and measuring these “reconstructed costs.” The expert responded by presenting a model that addressed incurred historical costs, the matching concept, differential costing, cost behavior information, and a variety of other CM concepts essential to the case. His testimony also addressed the accuracy of the cost measurements and the approach used to verify the costs.

The outcome? The court found for the bank holding company, awarding it more than 95% of the applied-for tax credits. Although this was a U.S. Tax Court case, the relevant testimony was almost exclusively related to CM accounting issues and showed the true value of forensic accounting.

Case 2: Contested Late Fees

In a large metropolitan area, a major cable company charged late-paying customers a $5 fee if they didn’t pay their bill on time, as defined by their contract. Nevertheless, a law firm filed a class action suit against the cable company, alleging it was overcharging customers for late payments. Under the law, individual customers could be charged a late fee provided that the amount charged was no more than the actual costs incurred by the cable company in servicing the late-paying customers (the theory of liquidated damages).

The plaintiffs in the case hired an expert who argued that the cable company incurred very little cost servicing late-paying customers because virtually all of the infrastructure and skills required to take care of these customers were already in place to service customers who paid on time. This expert alleged that virtually all of the late charges violated the applicable law.

The defendant in the case (the cable company) hired a forensic accounting expert with CM expertise to identify and measure the incremental costs of servicing late-paying customers. She reviewed all of the additional actions/services that the cable company had to perform because of the delinquent payers and also calculated the various costs of those extra services. This forensic accountant argued before the court that it wasn’t the nature of the service but rather the amount of service that’s performed for customers that drives costs. Therefore, if late-paying customers cause the cable company to perform more routine services, the cost of those additional services is incremental to the normal costs of doing business.

The expert’s testimony demonstrated that the cost of servicing late-paying customers was clearly greater than the late-charge amount. The forensic accountant’s expertise was thus instrumental to the cable company’s winning the case.

Case 3: Antitrust Accusations

A large grocery chain that commanded almost 50% of retail grocery sales in a fairly large Midwestern city was sued by another, smaller grocery chain, which alleged its competitor violated federal antitrust laws in an attempt to monopolize the local market. The case was initiated after a big-box grocery chain entered the market, forcing other retail grocery stores in the area to compete—at least in part—on prices. The result was that most, if not all, of the grocery chains in the area lost money over a roughly 20-month period.

U.S. federal antitrust laws have a number of components, but a key one is proving that the defendant in the case has engaged in predatory pricing, defined as pricing products or services so low that the only plausible explanation for this action is that the defendant is attempting to drive the competition out of business—and, once it’s achieved, will raise prices and reap monopolistic profits. To operationalize this standard, courts have maintained that predatory pricing occurs if a business sells its products or services below its average variable costs.

Of course, virtually no companies capture and report costs by their cost behavior patterns. Therefore, to prove predatory pricing, or to defend against that allegation, it’s necessary to analyze a company’s cost behavior patterns and relate them to the sales revenue. In this case, the big-box grocery chain sought the services of a forensic accountant with strong CM skills to perform an analysis that would show that the company, in spite of experiencing 20 months of losses, hadn’t sold its products below its average variable costs.

Before addressing the court in person, the expert carefully analyzed cost behavior patterns for all of the key cost categories for each store in the geographic area identified in the lawsuit. He performed regression-correlation analyses and used other relevant cost analysis methods to provide the court with a clear and convincing argument that the defendant hadn’t violated antitrust law. As such, in this particular case of David vs. Goliath, Goliath won.

WHERE YOU COME IN

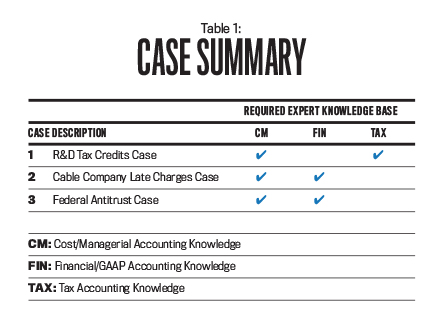

In each of these three very different types of cases, the CM knowledge and skills of a forensic accountant were essential to the successful outcome. (Table 1 shows the expert knowledge used in the three cases.) Therefore, it’s almost impossible to overstate the importance of CM knowledge and skills in the field of forensic accounting. Virtually every case, at least in the damages phase, requires the services of one of these experts.

As a corporate management accountant whose company may be under threat from a competitor or regulatory body, you may have occasion to work closely with a forensic accountant or a team of them. It’s important to familiarize yourself with the material risks to your organization and the various forensic solutions that are available to you. This extra effort may allow you to spot possible holes in your accounting information systems, propose remedies, and plan future strategies, all of which are integral to any organization looking to stand out in an increasingly competitive global environment.

March 2018