IBM Security and Ponemon Institute report that in 2017 the average total organizational cost of a data breach involving the exposure of customer or personnel data in the United States was $7.35 million, according to the “2017 Cost of Data Breach Study: Global Overview.” As we know, however, some companies experienced far more severe losses.

The most dramatic of these was Equifax. In 2017, the credit monitoring firm reported that a data breach of highly sensitive information—including birth dates, addresses, credit card numbers, and Social Security numbers—impacted roughly 145.5 million people in the U.S. Company reports indicated that hackers accessed data between mid-May and July through a vulnerability in a web application. While final costs to Equifax are still being tallied, the initial financial impact of the breach was a 12-month decline in net income of 27%.

Meanwhile, another hack, called WannaCry, infected the computer systems of large multinational companies such as FedEx and Nissan and institutions around the globe, including colleges in China. As a result, some companies paid bitcoin ransoms while others lost core operations. Nevertheless, other, more serious impacts were felt by the wider public: Clinics and hospitals in the U.K. suffered a massive outage, causing delays in surgeries; telephone service in France was disrupted; train travel was affected in Germany; and the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs had untold interruptions in its internet services.

A GLOBAL HEADACHE

In its 2017 survey of 92 U.S. companies, Willis Towers Watson found that one in five companies had suffered a cyber breach in the last year. In many cases, the companies themselves may have been to blame, the survey indicated. For instance, 16% of respondents reported incidents in which senior leaders put confidential information at risk over the last three years.

Two-thirds of the respondents surveyed see cyber risk as a fundamental challenge to their business, and 85% view cybersecurity as a top priority for their companies. Nevertheless, many have been slow to take defensive positions: Half of the companies surveyed by Willis Towers Watson have implemented various risk management activities but haven’t formally articulated a cyber strategy. In fact, only one in nine firms has adopted written objectives and goals for its cyber risk program.

This is about to change. The same study shows that the vast majority (85%) of companies will embed a culture of cyber risk management within three years, and 72% will improve business and operating processes within the same time frame to bolster cybersecurity. (For more information, see “Decoding Cyber Risk: 2017 Willis Towers Watson Cyber Risk Survey” at http://bit.ly/2u1KZGo.)

While the role of the CFO in this arena is still a moving target, many observers are calling for the finance chief—not the CIO or chief risk officer—to lead the charge in ensuring company data is safe and that investors are well informed about any risks related to cyber attacks and data security. As Steve Vintz, CFO of Tenable, a cyber risk management solutions company based in Columbia, Md., comments in a recent Harvard Business Review article, “Given the increasingly new relationship between cyber risk and financial risk, the CFO should ultimately be accountable for cyber risk.” (See “CFOs Don’t Worry Enough About Cyber Risk” at http://bit.ly/2DHB2Ny.)

IT’S THE LAW

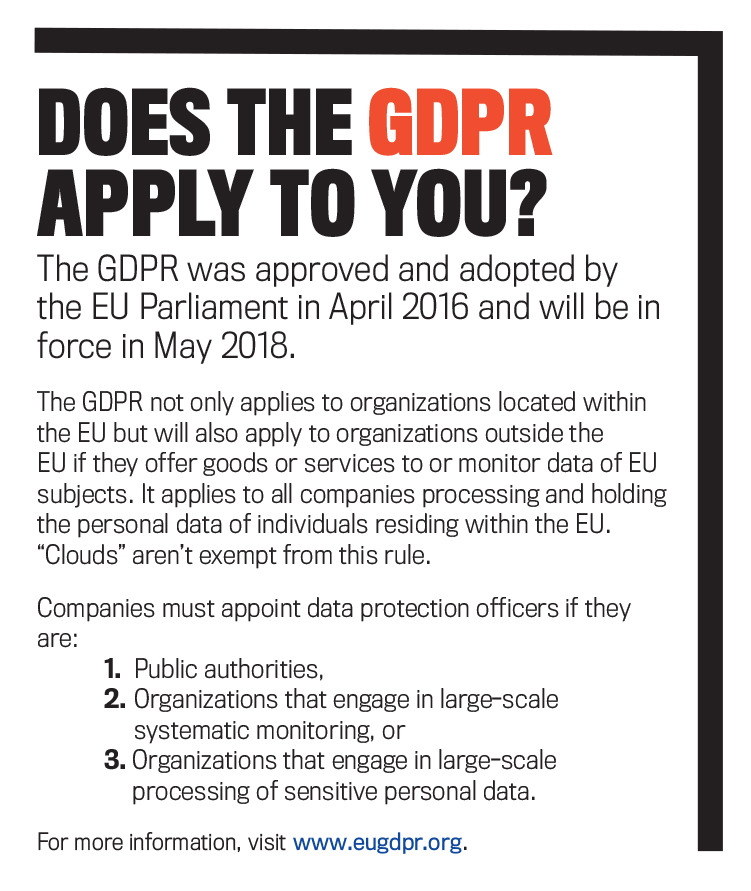

The European Union (EU) has recently undertaken measures to ensure that preventing cyber risk becomes the CFO’s responsibility.

In May 2018, the EU’s newly inked General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) takes effect. Violations of these rules that result in data breaches could cost companies up to €20 million in fines or 4% of global annual turnover for the preceding financial year—whichever is greater. The provisions of the GDPR draw a straight line between a company’s data risk management practices and the office of the CFO. (For more on the GDPR, see “Does the GDPR Apply to You?)

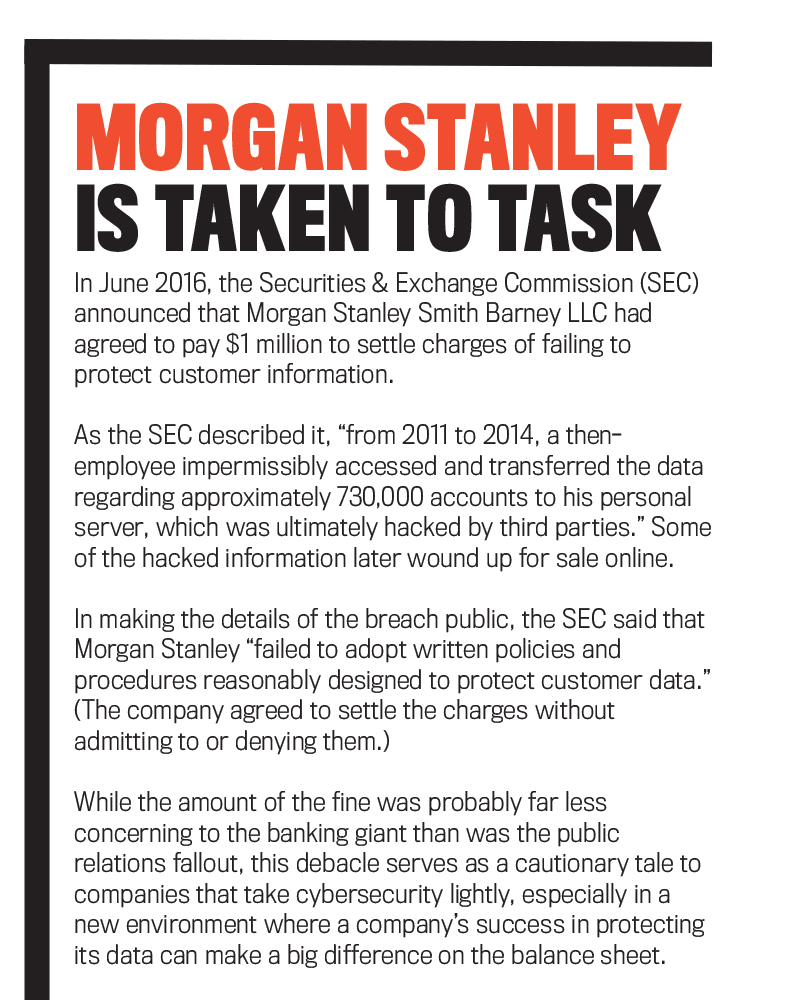

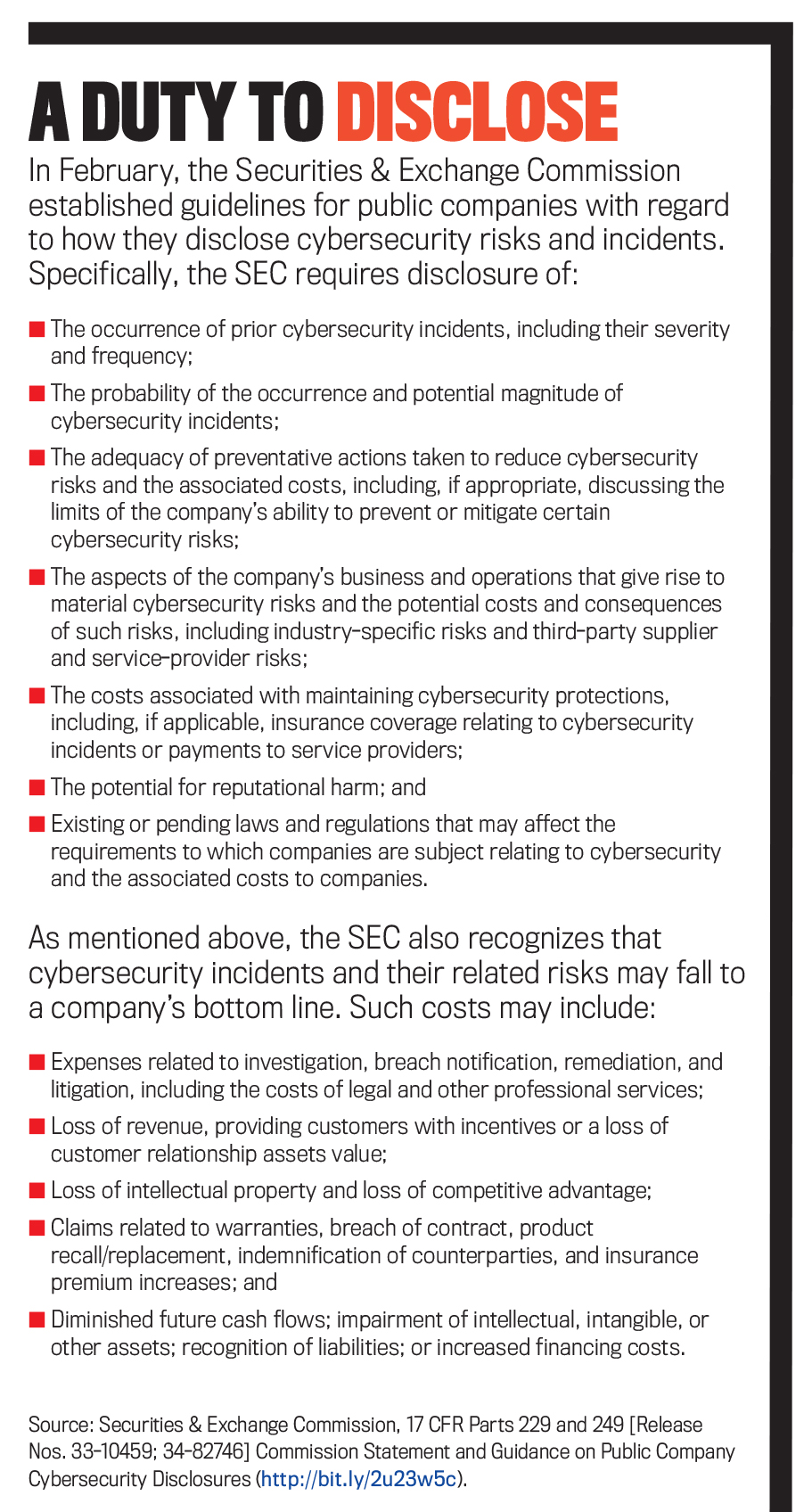

In response to the increased incidence of cyber risk in the U.S., the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) is also taking measures to ensure cyber risk governance and disclosure are top priorities for CFOs. On February 21, 2018, the SEC published updated guidance on how public companies should disclose cybersecurity risks and data breaches, broadening the scope of disclosure from its initial 2011 rule and strengthening the relationship between cyber risk, financial risk, and the company’s ongoing viability.

The SEC extended this guidance to risk factors that may arise in connection with acquisitions (a potentially huge risk analysis and disclosure assignment across the board) and suggested that companies “consider the impact of such incidents on each of their reportable segments.” (A summary of the new requirements can be found in “A Duty to Disclose.”)

While this appears to be a significant step forward in terms of protecting investors, more disclosure around cyber risk has thus far received little support from the corporate community.

The uptake has been slow for a variety of possible reasons, not the least of which might be the potential negative impact on corporate brands and investor perceptions. In fact, three professors at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb.—Edward A. Morse, Vasant Raval, and John R. Wingender, Jr.—recently found that disclosing cyber risks in company 10-K and 10-Q filings has had a negative impact on company share prices. (Their article, “SEC Cybersecurity Guidelines: Insights into the Utility of Risk Factor Disclosures for Investors,” was published in the Winter 2017/2018 issue of The Business Lawyer.)

The authors examined the filings of roughly 200 companies with publicly traded common stock that made their first cybersecurity-related risk disclosure pursuant to the SEC’s 2011 rule. The data revealed a significant decline in share values post-disclosure. “Rather than viewing disclosure as a positive signal of management attentiveness, investors apparently viewed it as a cautionary sign,” the authors concluded.

GREAT(ER) EXPECTATIONS

Given time, however, investors will come to view cybersecurity efforts in a positive light, predicts Stewart Curley, CFO of LookingGlass Cyber Solutions, a global cybersecurity and intelligence company based in the U.S. He explains that investors will eventually come to understand the evolving regulatory environment, which will compel more disclosure, not less. “With increased regulation around cyber risk,” he says, “companies are clearly moving towards improving corporate governance, and over time this will be the norm. In my view, investors will also demand a greater understanding of risk across the entire supply chain.”

For example, in New York State, the new Stop Hacks and Improve Electronic Data Security (SHIELD) Act requires companies that handle sensitive data to adopt comprehensive programs to not only monitor and report on their own security position but also on the positions of their major suppliers. Similarly, covered entities that are regulated by New York banking, insurance, and finance laws are required to have a written cybersecurity program that extends to the management of vendors and third-party service providers. Companies that meet or exceed the state’s measures can qualify to receive safe harbor from enforcement actions under the SHIELD Act.

The rationale for extending accountability beyond company borders is clear. “You can have everything buttoned down neatly, but if you’re working with a trusted contractor or other entity that doesn’t have that same level of security, you’ve created a significant risk,” Curley notes. These new regulations, he explains, require companies to think beyond their own networks into the extended networks they work with.

THE CALL TO ACCOUNTANTS

Not only are improvements in cyber risk management and disclosure being driven by regulatory bodies, but they’re being ingrained in accounting training and standardized practice as well. According to a February 2016 joint study by IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) and ACCA (Association of Chartered Certified Accountants) titled “Cybersecurity—Fighting Crime’s Enfant Terrible,” “What is needed, but is still often lacking, is a strategic approach to mitigating cybercrime risks.” Accordingly, IMA and ACCA recommend that accountants and finance professionals play a leading role. More specifically, this role would include:

- Creating reasonable estimates of financial impact that different types of cybersecurity breaches will cause so that a business can be realistic about its ability to respond to an attack and/or recover from it.

- Defining risk management strategy and helping businesses establish priorities for their most valuable digital resources in order to implement a “layered” approach to cybersecurity.

- Following closely the work of governments and various regulators in order to have clear, up-to-date information on relevant legislation and on requirements for adequate disclosure and prompt investigation of cybersecurity breaches.

In April 2017, in an effort to provide a consistent reporting platform, the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA) unveiled its cybersecurity risk management reporting framework. As AICPA Executive Vice President for Public Practice Susan S. Coffey points out, “While there are many methods, controls, and frameworks for developing cybersecurity risk management programs, until now there hasn’t been a common language for companies to communicate about, and report on, these efforts.” (AICPA press release, April 26, 2017)

And in November 2017, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) cautioned that it will turn a spotlight on audit quality related to cyber risk, reminding auditors that it’s important to consider whether there are cybersecurity risks that could affect the accuracy and completeness of financial statements and whether there are any implications for internal controls over financial reporting.

A COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE?

According to Richard Swinyard, managing partner and CFO at Computer Integrated Services (CIS), a U.S.-based identity and access management and network security firm, the heavy focus on data security and compliance in the audit world is something that should be driving CFO behavior. At the same time, he adds, “If people can show that they’re ahead of the curve—that they’re going slightly above requirements—it can be a real competitive advantage.”

Yet CFOs still have a long way to go to get up to speed with this evolving cyber risk management and reporting ethos, says Stewart Curley, who believes there’s still some naïveté around cybersecurity. “A lot of CFOs feel that they have basic protections in place that will take care of cyber risk, not realizing that they really need to move to much more sophisticated defenses to keep up with the skills of the attackers.

“Many companies also rely too much on [data protection] insurance,” he adds, “whereas there needs to be more focus on remediation.”

CFOs also need to be forward-looking when it comes to cyber risk and not rely on compliance alone as an effective tool against cyberattacks, Curley warns. “When it comes to the cloud, for example, companies rely too much on the effectiveness of third-party audits. I’ve certainly seen times over my career where companies have met all the technical requirements from a compliance standpoint, but still had some pretty big holes that hackers could get into. Companies need to focus more on the real vulnerabilities that they have, and maybe less on the compliance or paper documentation that makes it look like they’re doing the right things.”

For a CFO, this means understanding not only the constantly changing regulatory environment but the cyber risk implications of the company’s investments in new technologies as well. According to Swinyard, although not firmly under the banner of the CFO, “we’re increasingly seeing the shift of responsibility there, or at least joint responsibility between the CFO and the chief technology officer of the company.”

Swinyard likens the evolving relationship in the cyber risk space to the one that evolved as a result of cloud computing. “If we go back five years, CFOs were being told, ‘We’re moving to the cloud because it’s going to save us money.’ Suddenly, we had to start working more closely with CIOs to figure out how we were going to implement cloud-based strategies. I think cybersecurity has become the next phase in this business relationship.”

THE AUDIT FACTOR

Another reason cyber risk management is migrating toward the office of the CFO is because of ever-changing and potential future audit and reporting requirements. Swinyard notes, “We have seen companies being told they have a going concern risk (especially after cyber attacks) because they don’t have tried and tested business-continuity programs in place and/or because they had no strategies around employee identity and access management or testing for and managing vulnerabilities to cybersecurity attacks.” He adds that this goes to the heart of the CFO’s job. “What CFO wants to have an independent expert report that goes externally or to their board of directors and says, ‘We found all these control deficiencies and weaknesses within this company on their watch’?”

But the biggest challenge when it comes to the CFO’s role is climbing the learning curve and then putting the math to it, Swinyard says. “The key is building the knowledge to be comfortable when making decisions on what’s acceptable financially. There is a fine balance that is hard to strike—you don’t want to leave yourself exposed because you’ve done too little or in financial distress because you’ve spent too much.” That’s particularly true for small and medium-sized businesses, he notes.

Whether CFOs are increasingly involved in cyber risk management because of potentially devastating exposure to cyberattacks (read: Equifax), the evolving regulatory and audit environment that’s driving changes in reporting and disclosure around the world, or the framework guidance emerging from the accounting bodies, one thing is clear: Companies will continue to look to their finance chiefs for broad-based leadership. The decade of the cyber CFO is truly here!

©2018 by Ramona Dzinkowski. For copies and reprints, contact the author.

April 2018