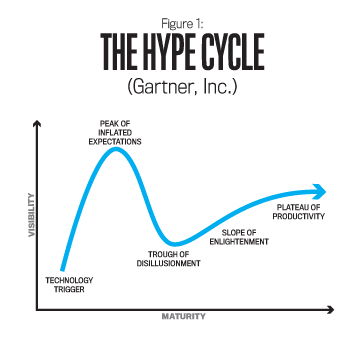

When gamification became a trend several years ago, companies everywhere rushed to join in on the hype. In 2011, Gartner, Inc. predicted that 70% of global organizations would have at least one gamified application by the end of 2014. But by 2013, Brian Burke, research vice president at Gartner, warned in a Forbes article that 80% of companies using gamification would fail to meet business objectives by 2014.

Like many trends that are implemented quickly, gamification didn’t always deliver the results companies wanted. Attempts were often put into place improperly or with little planning or foresight. In a 2014 Fast Company article, Adam Hollander said, “In my experience, poor gamification design is a direct result of not identifying (and being able to measure against) key business problems a company is looking to solve.” And Guy Fogel, in a May 30, 2015, article for www.gameffective.com, said, “Gartner was spot on…because the gulf separating good gamification design from poor gamification design is far and wide.”

Though the hype has died down for gamification, it still provides value and opportunity for companies looking for new or different solutions to age-old problems. Jim Wexler, president of gaming consulting firm Experiences Unlimited, takes an optimistic long-term view of gamification, noting, “Although the word ‘gamification’ was recently coined, games-based learning has been around a long time.” For example, the use of flight simulators to teach military and airline pilots how to anticipate emergency landing situations was a well-established practice before gamification ever became a buzzword.

Companies in many different business sectors use gamification, including accounting firms. In 2013, Jeanne C. Meister reported in the Harvard Business Review that integrating gamification into the Deloitte Leadership Academy caused a 37% boost in the number of users who returned to the website every week. In another example, KPMG’s Joey Lynn Monaco, associate director of technology-based learning, consults with internal clients to transform noninteractive lectures into interactive learning experiences. She focuses on creating compelling learning games and immersive learning simulations.

Accounting firms also find gamification useful in recruiting employees. PwC Hungary lets job applicants use a game called Multipoly to test their readiness for working at the firm. And McGladrey, the fifth largest U.S. accounting firm, has potential new hires play a two-hour scavenger game called cityHUNT, where recruiters can evaluate their behavior in real time. “It is not fake and recruits leave pumped up about our culture,” said Gabrielle Nader, talent acquisition specialist at McGladrey.

TRAIN EMPLOYEES

Gamification has been used in employee training for many years. For example, gaming principles have been a part of state agency LeanOhio’s employee training (see “LeanOhio: Gamifying Government”). LeanOhio’s mission is to make Ohio government “simpler, faster and less costly.” According to Steve Wall, the retired founding director of LeanOhio, the initiative also incorporates “belts and ladders” into its process. Trainees receive cameo belts after completing boot camp, the first step in the process, and can progress to the final prized master black belt, where they present a portfolio of results before a panel of judges.

When it comes to training, Mark Spratt, a director in PwC’s People and Organization practice, says, “Younger folks need a learning experience that is less traditional, not lecture based.” Wexler points out that “children born between 1985 and 1995 are walking into corporations with a training environment from 1955.” Gamification provides an alternative—a “fun-based way to change behavior and teach complexity,” he says.

One form is using simulations to teach. Spratt offers an example where teams might tackle scenarios on how to treat vendors or deal with bribery. A simulation could ask employees what to do in a crisis such as a fire. Teams then work on solving problems as managers evaluate those solutions. The key is to make it enjoyable. “Games must make an emotional connection with employees to be effective,” Wexler explains.

Gamification can also improve compliance with corporate travel policies. Ovation, a travel management company, awards employees points when they act in ways that align with their company’s travel policies. Employees can then use their points to shop for merchandise at digital stores.

Eric Gordon, founder and executive director of the Engagement Lab at Emerson College, believes games allow for failure toward mastery. “Learning happens as individuals [try] to reflect upon failure and attempt to get better,” he notes. Participants learn because games provide a structured, safe learning environment.

Tim West, an associate professor in the accountancy department at Northern Illinois University, uses this “low stakes” approach to learning by taking students to The Second City improvisational comedy center in Chicago, Ill., to receive training in communications. Students play a series of “improv” games to practice listening and team-building skills. After each game and much laughter, Second City actors reveal the lessons behind the games.

Shannon Polly, leadership coach and founder of Shannon Polly and Associates, also uses “improv” to teach communications skills, primarily to new managers. When individuals move to a higher position, they are “no longer just technical experts anymore,” Polly says, “They need to manage a team but can become results driven, saying, ‘I want it done and I want it done now.’ This might not be the way to get the best out of your people or to build a relationship.” Improvisational games offer great tools for teaching listening and collaboration skills to these new managers.

ENGAGE CUSTOMERS

Organizations also use gamification to attract customers. For example, the Web-based game, Pass It On!SM, once offered by AXA Equitable Life Insurance Company, helped women think about planning for unexpected events of the future. AXA wanted to reach women with the game because they are often the financial decision makers in the home and an undertapped market. AXA’s strategic goal for the game was to sell insurance to those households.

“I like the game,” said attorney Lois Palau, who started playing out of curiosity. “I am compulsively attached to it. You have to be very calculating to get ahead.”

As players traveled around the online game board, they ran into demons (problems in life) and gold (earnings in life). The game helped players plan their estate in case of an untimely death, with a financial scoreboard displaying what would be passed on to heirs upon a player’s death. According to game developer Wexler, AXA took “a complex problem that is boring and scary and engages women to deal with it.”

In 2012, financial services provider ING U.S. introduced STRUCT, a mobile game app designed to build awareness of investment and retirement planning. A video displayed strange creatures—animated blobs with arms and legs—running across the screen and throwing things, with the description urging viewers to “Join your crew—Clay, Mo and Tiny—as they race to build increasingly complex structures out of steel, wood and glass. Use the right mix of materials and you’ll be rewarded. But be careful—a wrong move could impact your strategy. Just like saving and investing, there are risks and rewards.”

The two apps had varied results. When still available in the iTunes store, STRUCT had 24,000 downloads compared to Pass It On!’s 315,000 downloads. According to Wexler, AXA’s Pass It On! “was fun to play and made an emotional connection to women” as opposed to STRUCT. Also, the right promotion can help—AXA promoted Pass It On! with a sweepstakes offering a prize of a $25,000 college scholarship.

ACHIEVE ORGANIZATIONAL GOALS

Organizations also gamify work processes to make work more fun. These efforts can increase profitability and help achieve financial goals.The United Kingdom’s Department of Work and Pensions created an innovation game, Idea Street, where employees share cost-saving ideas in a Web-based suggestions box. Participants rate ideas, creating a “buzz” index. By the end of the first year, Gartner reported that 4,500 employees generated 1,400 cost-saving ideas. The department implemented 63 of them for a savings of $32.6 million.

A team at Jo-Ann Fabric and Craft Stores—including industrial engineer Kulvir Khasa, general manager Cory Worth, as well as individuals from human resources and information technology specialists—created a game called S.P.A.Q. Ball to engage workers in the company’s distribution centers.

S.P.A.Q. Ball had two leagues of 10 teams each. Teams consisted of 16 members and included both production and nonproduction personnel. The teams competed against each other on a weekly basis. Scoring was based on team members’ performance on four key metrics: safety, productivity, attendance, and quality (abbreviated as S.P.A.Q.). Weekly standings were flashed on video screens at the distribution centers, and each season lasted one business quarter.

Team captains, who were often supervisors, drafted team members based on individual statistics related to the key metrics. The draft process took about two hours, and team captains assembled their teams carefully. “They loved it,” Khasa noted. “They said the draft is the best part of team building.”

To create an effective game, Khasa collected feedback from captains and players after the first cycle of the game. Criticisms included confusion about scoring and diminishing interest among the losing teams. Captains also suggested adding more incentives to the game, such as weekly prizes or more prizes.

Khasa revised the game to clarify scoring rules, adding consolation prizes and more teams to the playoffs. He also introduced weekly challenges, such as offering double points if all team members had perfect attendance for the week.

But gamification does require a financial investment. Khasa estimates Jo-Ann Fabric and Craft Stores spent $15,000 a quarter on S.P.A.Q. Ball for prizes and incentives. Indirect costs also included the time to create and administer the game.

According to the team captains, the game boosted morale and communications among all team members. Team captains gave “talking about the game” and “fun” the highest ratings on a satisfaction survey. At the same time, it provided a good return on investment because the game focused employee attention on the company’s primary measures of success. Khasa says the game yielded a 2% increase in productivity. “Although it might not seem like much…when a company is already close to 99% of its target goals, even a 1% increase is significant.”

ENGAGE COMMUNITIES

Community engagement offers yet another unique application for gamification. In Boston, Mass., the Boston Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics (MONUM) facilitated a partnership between the Boston Public Schools (BPS) Office of Accountability and Emerson College’s Engagement Lab to use the game platform Community PlanIt as a means to increase public engagement and collaboration in order to better inform BPS strategies and decisions.

The object is to use the online game platform as an innovative and effective way to promote public learning about complex issues. It avoids having to wade through a wide range of research and media outlets, which can be a time-consuming and aggravating task.

First, citizens learn relevant facts about education as they complete missions. They learn about improving attendance, closing achievement gaps (socioeconomic and racial), and graduation rates. Participants answer questions and complete challenges to advance in the game, earning badges and points as they compete with other participants.

After a few weeks of playing the game, city officials call a roundtable community meeting for discussions with the participants. “We have seen a different level of familiarity and a much higher level of discourse at the meetings,” says Nigel Jacob, cofounder of MONUM. The BPS game engaged 451 players with more than 4,600 comments. According to Jacob, the game brought many more voices to the table compared to the traditional community approach, where he said folks are “just yelling at each other.”

DESIGN FOR SUCCESS

Not all attempts at gamification work out. There are three important steps that are keys to success in adopting gamification: avoid pitfalls, design for return on investment (ROI) success, and measure success.

Step 1: Avoid Pitfalls

At first, gamification was in the beginning of what Gartner calls the Hype Cycle of technology development (Figure 1). Burke noted that hype occurs when companies have inflated expectations of what any new technology can do for their business. As a result, gamification might have “failed” because it didn’t live up to unrealistic business objectives. “Gamification is like an amplifier,” Wexler says, “You have to have proper sound first. You can’t make unappealing products or jobs appealing through gamification.”

Extrinsic rewards such as badges and loyalty programs can be short-lived. According to Wexler, Google Badges was one notable failure. Another one was the game Second City, “where avatars never really took off,” Spratt notes. These applications didn’t connect with players.

Furthermore, trust must be maintained throughout the gaming experience. “If newbies come in and get the same reward, then experienced players lose interest,” adds Michael Tresca, manager of digital and extended audiences communication at GE. Players will leave the game if they lose trust. Game developers must keep this in mind as the game evolves.

Step 2: Design for ROI Success

To improve the probability of gamification success, Wexler recommends building mastery and purpose into the games. For example, he asks the following questions when designing a game:

* What and why do you want to gamify?

* What do you want to achieve?

* What are your metrics for success?

* Is the game fun and easy to play?

Gamification fails when inexperienced people try to create a game. A company might use its public relations firm, advertising agency, or information technology (IT) department to gamify an application. But they won’t all get good results.

Developers “don’t know what they are doing,” Wexler explains, “[and] although the IT department can build a very good system, it is not experienced at reaching users at an emotional level.” Therefore, it’s imperative to ask the right questions and have the right members on the development team when designing a game.

Step 3: Measure Success

Spratt recommends measuring success and the ROI of gamification on several levels:

* Level 1: Did the players like the game?

* Level 2: Did the players learn anything?

* Level 3: If the game is used for training, did managers sit with employees to link the game to performance?

* Level 4: Have managers noticed a change as a result of the game?

* Level 5: What can make the game better?

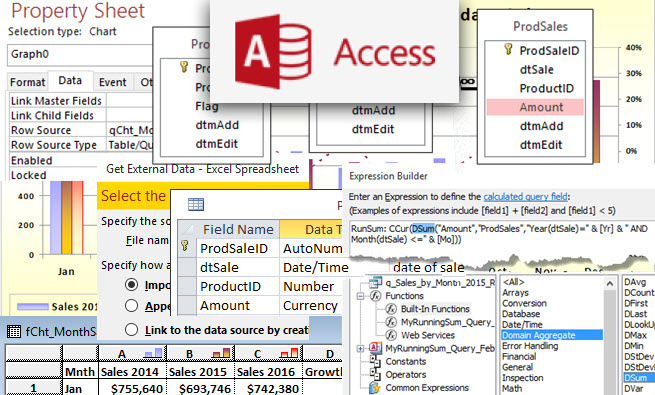

When management evaluates a game, they can improve it, leading to better performance: increased productivity, fewer errors, higher sales, and/or other cost savings. “Track everything and test often,” says Kelly Harper, director of customer experience learning at BMO Financial Group. Her company launched a financial literacy game to help its employees improve their financial welfare. The company measures the efficacy of its games by using pre-game and post-game measures, focus groups and surveys, and data evaluation (such as when people drop out of games). Evaluation is a key to implementing successful long-term gamification.

LOOK TO THE FUTURE

Successes and failures in gamification will continue as the industry gains more experience in using this tool. Accounting and financial professionals should consider gamification as another, although unconventional, way to meet organizational goals. Gamification can be simple or complex, taking on many forms, such as board games, video games, improved routines, social media, and apps.

Games have been linked to improved productivity, learning, public engagement, and even employee well-being. (See “Why Does Gamification Work?” for some of the proposed psychological and physiological reasons why gamification can be effective.)

For success, games must align with strategic goals in a fun and captivating way, making an emotional connection with their players. For long-term efficacy, management accountants should evaluate games for ROI and pursue ongoing game development to keep players coming back.

Although gamification isn’t a panacea, it’s changing the game of business. “Like e-mail, there is the chance that the market will become saturated and cluttered,” Wexler advises. “But like anything, good gamification will succeed.”

April 2016