This article is based on research funded by ACCA and IMA®.

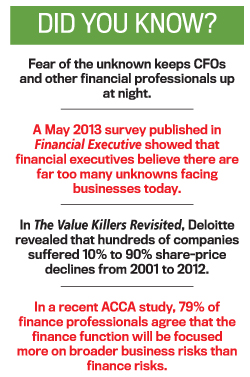

No company is immune from risk and uncertainty, and new approaches are needed to navigate risky environments. Creating a risk challenge culture should be a top priority.

For example, the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) notes that bad risk management cost the United States $13 trillion from 2007 through 2009. It attempted to correct this problem by mandating board risk oversight and the related disclosures (and, subsequently, implied risk processes). Further, in 2014, the SEC announced enterprise risk management (ERM) as a target of its “national examination priorities.”

While ERM is certainly part of the solution and has been shown to create value, reduce volatility, minimize surprises, and lead to better decision making, even a perfect ERM process can’t succeed without a risk challenge culture that supports it. As one board member stated in the 2012 study we did for the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), Improving Board Risk Oversight Through Best Practices, “The risk that kills most companies…is business risk. There are only a few things that go wrong, right? You were asleep and the market changed. You didn’t have the right people. You weren’t challenging the people to anticipate around the corner. You weren’t bringing in objective info that was contrary to management’s viewpoints so that you had a check and balance on how they see the world.”

In 2014, we published a study sponsored by IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) and ACCA (Association of Chartered Certified Accountants), A Risk Challenge Culture. The study posited the advantages of developing a different sort of culture for managing risk. This challenge culture would create an environment “that encourages, requires, and rewards inquiries that challenge existing conditions.” Unfortunately, examples of a poor risk culture are abundant.

TWO CAUTIONARY TALES

Two of the most severe and expensive—both in dollars and human suffering—examples occurred in different parts of the planet, in entirely different industries, and in vastly different circumstances. Yet both had roots in the seemingly innocuous confines of organizational culture. By our describing these incidents in some detail here, you’ll have a better idea of the true value of changing corporate culture to ensure that problems—no matter how inconsequential or highly unlikely they may seem at the time—are identified early and steps are taken to stop them from going further.

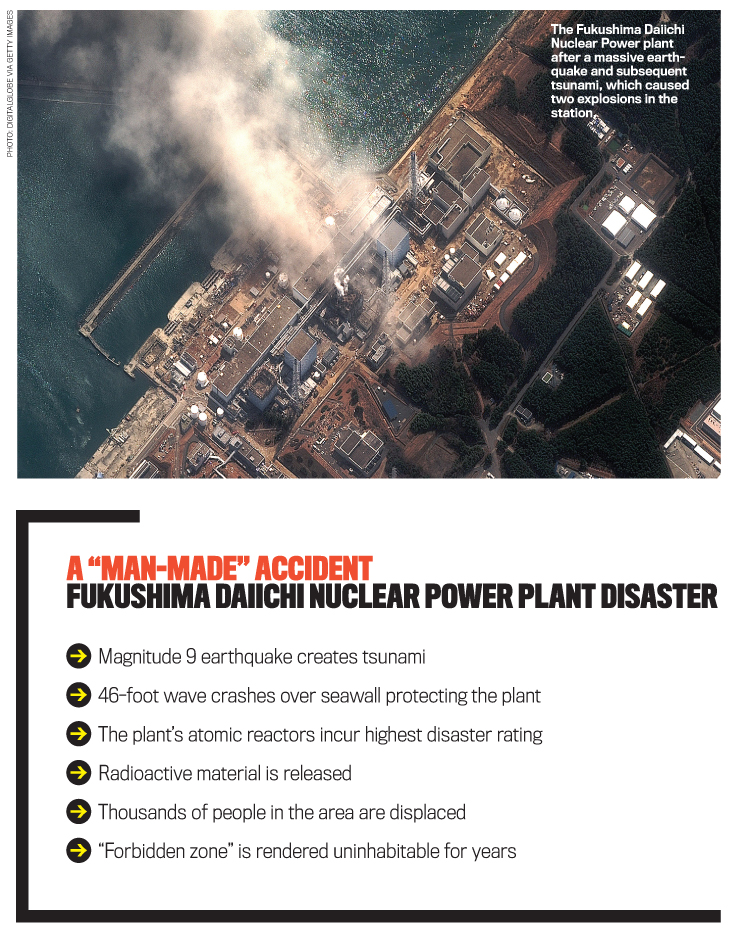

Fukushima Daiichi

After a massive earthquake and subsequent tsunami resulted in one of the worst nuclear disasters in history, the finger wasn’t pointed so much at Mother Nature but at human beings and culture. The Fukushima Daiichi disaster is rooted in one major, flawed assumption: that there would never be a magnitude 9 earthquake and tsunami greater than 33 feet in the region or that the probability of these events was so low as to be of no concern. Although Japan is considered seismically active, an earthquake with the strength of the one that hit on March 11, 2011, hadn’t occurred there, according to best estimates, since the year 869.

In late 2011, the National Diet of Japan (basically Japan’s Parliament) established an independent blue ribbon commission to investigate the accident. This was the first time the Diet had created an independent commission in modern times. The commission’s report, dated July 6, 2012, is scathing. (The executive summary in English is available at http://bit.ly/1H642On.) It concludes that Fukushima Daiichi wasn’t an accident at all but was “man-made.” The specific language even includes the somewhat surprising description of “Made in Japan.” But amid all the recitation of history, facts, and regulatory and corporate failures, the report identifies a key ingredient of the accident: Japanese culture.

“[The disaster’s] fundamental causes are to be found in the ingrained conventions of Japanese culture: our reflexive obedience; our reluctance to question authority; our devotion to ‘sticking with the program’; our groupism; and our insularity.

Had other Japanese been in the shoes of those who bear responsibility for this accident, the result may well have been the same.”

As the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant disaster showed us, just because something has no precedent doesn’t mean it can’t happen. A good ERM system recognizes this and puts in place contingencies in the event that the worst possible scenario comes to fruition. An executive who tells his or her team, “Well, this sort of thing will never happen, so let’s not waste any time worrying about it” is setting the organization up for a possible rude awakening.

General Motors

The General Motors (GM) ignition-switch debacle resulted from the failure of a 57-cent part that led to the deaths of at least 27 people, dozens of accidents, the recall of 2.6 million cars, and serious damage to the credibility and reputation of one of the world’s largest automakers.

As in the case of Fukushima Daiichi, a formal, commissioned report tells the unfortunate tale. In early 2014, GM’s board engaged a Detroit law firm to conduct an exhaustive study of the ignition-switch problem. The report, dubbed the Valukas report after its principal author, Anton Valukas, was thorough yet was completed in a matter of just a few months. The report is labeled “Privileged and Confidential,” but it’s freely available on the Internet and is even posted on the website of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (1.usa.gov/1LPhkCi).

The Valukas report was highly critical of a number of decisions GM made, but one topic of discussion stands out: the culture of GM as one of the main culprits in the debacle. According to the report, in the 2000s, cost cutting was a major concern at GM in every area except safety. (The Valukas team could find no evidence that any sort of cost-benefit analysis or overconcern with costs entered into the resolution of safety issues.) But in the case of the ignition switch, the decision to classify the problem as “customer convenience” began the disastrous chain of events that culminated in the product recall some nine years later.

It would appear that the GM culture at the time introduced a bias toward not classifying a problem as safety related, a decision that could potentially lead to enormous cost savings. Coupled with this calamitous classification, the report uncovered evidence that GM encouraged the use of amorphous committees and task forces, which kept only sparse records of meetings and seemed intended to diffuse individual accountability. Indeed, there were references in the report to the “GM salute” (crossing of the arms and turning to another as if identifying that person as responsible) and the “GM nod” (everyone in a meeting nodding agreement to a course of action, then promptly ignoring it after the meeting). There also appeared to be an undocumented practice at GM to not commit very much to writing so as to thwart the discovery process in product liability lawsuits.

Even when the ignition-switch problem finally was identified, GM was very slow to take action. Nine months passed before the recall in early 2014. GM’s board wasn’t even made aware of the issue until the time of the recall. The Valukas report chalks this up to a cultural issue and tradition that crossed over to the post-bankruptcy GM: the need to find the ultimate “root cause” before ordering a recall. According to The Wall Street Journal, GM’s board faces three lawsuits (the company faces more than 60 potential class-action suits) over its duty to act. Somewhat belatedly, GM has stated that board risk oversight will be improved.

The business press tended to paint the picture as the saga of a “rogue” employee, who, on his own and secretly, hid the ignition-switch problem from the company. (See, for instance, “How one rogue employee can upend a whole company,” Fortune, http://for.tn/1nPyiSi.) GM’s CEO even suggested that the engineer in question perjured himself in testimony in 2013.

But it would seem that the real culprit in the ignition-switch mess was a corporate culture that was motivated to ignore problems rather than fix them.

What can be done to create a culture that would prevent events like these from happening?

THE RISK CHALLENGE CULTURE STUDY

Since the late 1990s, enterprise risk management has been regarded as the touchstone of comprehensive risk management systems in organizations. But it’s clear from the Fukushima Daiichi and GM debacles that organizational culture can be a strong—and pretty much unexplored—contributing factor in the success or failure of an ERM program. As with any revolutionary initiative, one of the dangers in ERM implementation is the “form vs. substance” dilemma: An ERM system looks good on paper, but operationally it doesn’t work very well. It’s sobering to think that “doesn’t work very well” could translate into people being killed and valuable property being destroyed.

The relatively new idea of a challenge culture is a path out of this conundrum. It might be easier to view a challenge culture in terms of what it isn’t. Here’s what the 2014 ACCA-IMA report had to say about it:

“A challenge culture is an environment that encourages, requires, and rewards enquiries that challenge existing conditions. When a subordinate is afraid to ask senior management about perceived risks, that is not a challenge culture. When a board member is satisfied with the CEO’s facile answer to a serious risk issue, that is not a challenge culture. When board members ‘rubber stamp’ management’s critical actions without serious debate, they have not acted as befits a challenge culture.”

An ERM program that looks good on paper but is fatally flawed when called into action could be worse than no risk management system at all because it gives people a false sense of security and keeps them from developing an effective structure.

Much of our study is based on the insights of business professionals. We developed a preliminary list of nine essential elements of a risk challenge culture based on our previous experience with ERM. Then we solicited input from participants in ACCA-IMA roundtables we conducted in New York, London, and Dubai, as well as from attendees at an ACCA-IMA Accountants for Business Global Forum. Each of these occurred in fall 2013. Participants in the roundtables and the forum were experienced business professionals who have dealt regularly with critical risk issues. We asked them about risk cultures in general and the adequacy of our list through a series of relatively open-ended questions. Then we asked them to further explore the issues we had raised.

The participants validated our list and shared keen insights into the cultural issues attendant to risk management. One of the London roundtable members noted: “In terms of risk culture, you’re not wanting to avoid risk taking. You’re wanting to have responsible risk taking. So your risk culture needs to make sure that people understand that innovation, new ideas, creative thinking—all of those things—are still important.”

NINE ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS

Here’s a brief overview of the nine essential elements of a risk challenge culture:

- Professional skepticism and board oversight of risk. A risk challenge culture begins with the board of directors and the C-suite, who set the required tone at the top. They should approach risk oversight with a questioning mind and make critical assessments of the effectiveness of their organization’s risk management processes. A useful approach for every possible risk scenario should include a series of “what if” questions that look beyond what presently exists and thus may lead to some “ah-ha” moments for the executive team.

- Board diversity and development of expertise in ERM. To inculcate a risk challenge culture and perform its responsibilities in risk oversight, a board should embody a diversity of skills and experiences and be knowledgeable about a holistic approach to risk management, such as ERM. Without both, the board itself may be a risk factor. The board may very well require training in ERM, and, as noted by one of our roundtable participants, “The chair of the board needs to plant the seed for training. And if that person doesn’t get it, it’s likely to be suboptimal for the rest of the board.”

- Conversations and roles in a risk challenge culture. The requisite roles to lead and sustain a viable risk challenge culture include the board and its committees, the chair and CEO, and other C-suite executives. The board (in collaboration with the chair and CEO) should foster a level of openness and frankness expected in risk management discussions. Not surprisingly, the tenor of discussions at that level has an impact on the conversations cascading down the management chain. Risk professionals like the chief financial officer (CFO) and chief risk officer (CRO) must have the authority to rein in risk taking when deemed appropriate and the leadership skills to manage the inevitable arguments that may result.

- Information asymmetry and risk reporting. Information asymmetry is the difference in information between the board and management, and, unfortunately, that gap is growing. Information asymmetry occurs when executives filter what the board sees or when management delays passing appropriate information to the board. Without that knowledge, it’s difficult for board members to fulfill their risk-oversight and duty-to-act responsibilities. Some risks can materialize so quickly that any delay can be devastating for a company. Ensuring that the board has extensive access to management is one way to mitigate filtering.

- Decision making and cognitive biases. A significant impediment to the success of a risk challenge culture is the set of cognitive biases that can affect decision making. Some of the common biases applicable to risk issues are:

- Anchoring—an overreliance on one trait or piece of information.

- Loss aversion—being more aggressive in avoiding losses than in seeking gains.

- Overconfidence—exaggerated faith in your own solution to problems.

- Confirmation—the tendency to seek out evidence that confirms an initial decision or preconception.

- Rushed problem solving—an overeagerness to solve a problem quickly.

Board members and executives must learn to combat these issues so that the real risks to the business are seen and understood.

- Risk appetite. In a risk challenge culture, there should be a mechanism in place for the board and senior management to communicate to all levels of the organization how much risk the organization is willing to accept (appetite) and how much risk it’s able to take on and still operate prudently (tolerance). Studies have revealed that less than a third of organizations have developed a formal risk appetite statement. The exception is the financial services sector.

- Strategy and risk. Strategy and risk are inextricably linked; they may even be viewed as two sides of the same coin. We can argue that one of the fastest paths to massive value destruction is to undertake a strategy without a thorough consideration of the attendant risks. In a risk challenge culture, all stakeholders should demand that the link between opportunity and risk be constantly at the forefront in strategy deliberations and continually updated as conditions warrant.

- Incentives and risk. In a challenge culture, behaviors motivated by incentives need to be anticipated and assessed as to whether they’re consistent with the organization’s risk appetite and overall strategy. The consequences of not doing so can be potentially devastating to the organization, especially in this era of volatile and complex derivative contracts and extremely rapid technological changes. For example, JPMorgan Chase’s well-known $6 billion “London Whale” loss in 2012 resulted in part from an incentive structure that rewarded extreme risk taking in highly volatile derivative instruments.

- Risk culture: assessment, diagnostics, and signs. When an organization’s risk culture is working properly, there’s an alignment of the common purpose and attitudes toward risk. A misaligned risk culture can reveal itself in negative events, such as taking excessive risks. It’s possible this is what happened at GM. Without the proper risk culture, an ERM process can’t work and boards can’t fulfill their oversight duties.

The first step for most companies, therefore, is to measure and gauge their current risk culture. Once everyone understands the culture, positive changes can begin to happen.

A NEW WAY OF THINKING

When companies are in trouble, executives frequently say they need to fix the culture. As one participant in our study noted, “The disruption hits, and you’re totally unprepared, both in terms of your balance sheet and your culture. So you have to go in with the mind-set that this is serious stuff.”

In response to the recent lawsuits against GM’s board, the company noted that how risk information flows would be reviewed and that board risk oversight would be enhanced. While these actions certainly are laudable, they’re about nine years too late. It’s better to strengthen board risk oversight now, not after a debacle. You can use the elements we’ve discussed here to bring the conversation about the creation and operation of a risk challenge culture to your own organization…and avoid an in-house risk tsunami.

April 2015