International issues have a strong impact on the budgeting activities of global companies. In the first article of our series (“Managing International Operations in Uncertain Times,” Strategic Finance, November 2020), we described how volatile external factors such as foreign currency, interest rates, and inflation rates influence overall and specific budget preparation and use. In this third and final article, we address several strategic issues, including transfer pricing, inventory policy decisions, and supply chain dysfunctions.

As you know in your role as a management accountant or financial professional, strategic planning is an essential activity for any business. This type of forward focus motivates and, in some cases, mandates that managers look beyond the “here and now” toward where they want to be in 12 months, two years, and beyond. More often than not, the budget or profit-planning activities move the strategic plan from ideas to implementation. (In addition to the previously mentioned article, see “Budgeting for International Operations,” Strategic Finance, December 2020.) This final article will concentrate on several commonly encountered yet critical strategic elements to be examined when the international operations of a business represent a significant portion of its economic activity.

THE INS AND OUTS OF TRANSFER PRICING

Transfer pricing plays a significant role when budgeting in an international setting. Similar to domestic budgeting, transfer pricing is a policy decision that influences the profitability of different operations within a global corporation. Although the transfer price of goods and services traded internally may be an uncontrollable factor at the division level, it eventually becomes controllable at a higher profit or cost responsibility center. Ultimately, foreign subsidiary managers in particular shouldn’t be held accountable for the profitability of their operations if they can’t control this factor.

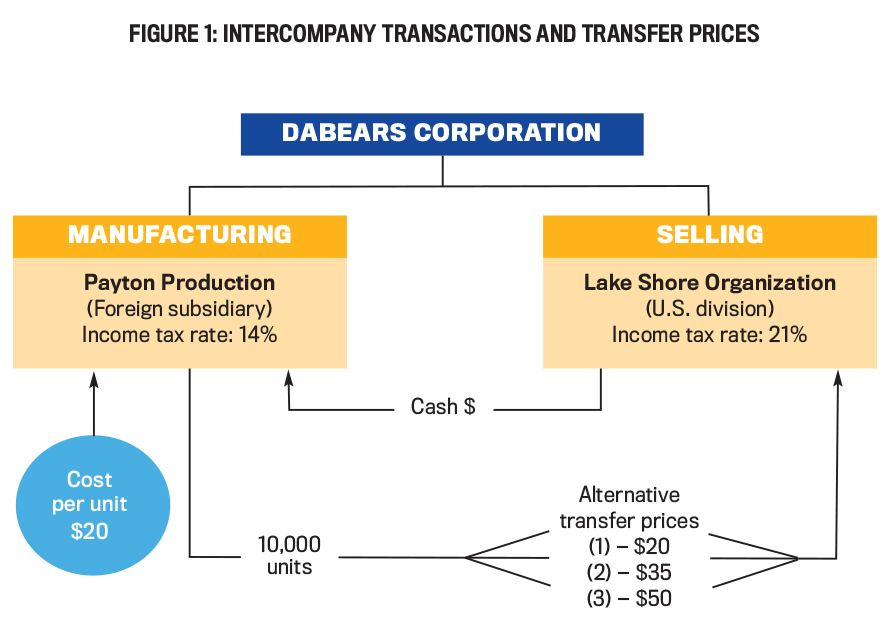

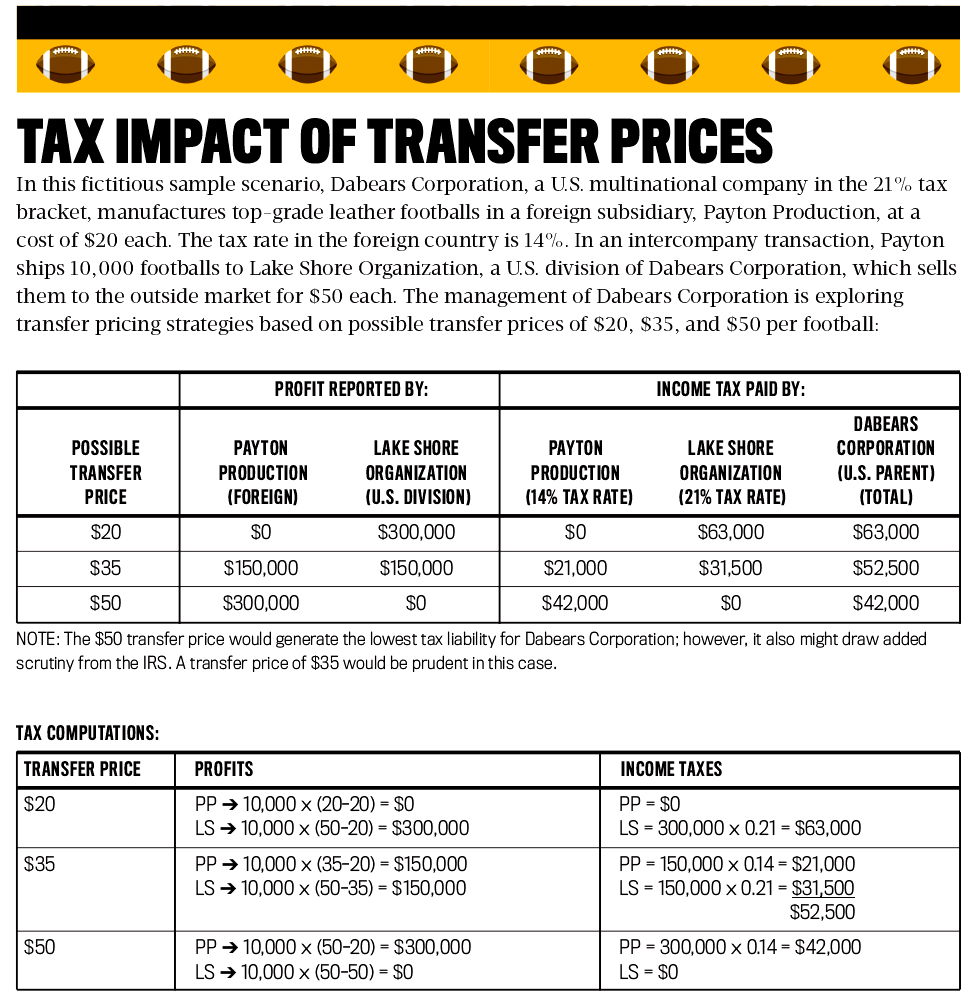

In international budgeting, transfer pricing can be used to the company’s benefit in a wide variety of situations, including taxes, tariffs, exchange controls, credit status of affiliates, profitability of the parent company and foreign subsidiaries, and reduction of exchange risks. The most frequent abuse of transfer pricing policies involves companies that manipulate the price of internally traded goods to reduce their taxes in high-tax jurisdictions, thereby shifting profits to a country with lower tax rates. Figure 1 and “Tax Impact of Transfer Prices” illustrate a typical intercompany pricing decision involving tax planning strategies.

In the meantime, governments continue to increase their efforts to enforce arm’s-length pricing between foreign and domestic operations of multinationals by applying their own estimates for the value of the traded goods or by imposing minimum value-added requirements for production. This usually involves using more expensive local inputs, which results in higher costs for a multinational operation. Corporate policy makers must therefore be aware of the benefits and limitations of transfer pricing while establishing a policy that satisfies the multinational company, its subsidiaries, and government guidelines.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT APAs

Companies domiciled in the United States can take advantage of an advance pricing agreement (APA). This involves a multinational company and the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS)—the agency that checks that an “arm’s-length transaction” price is in place—entering into a transfer pricing negotiation. The APA establishes an acceptable price for the transfer of merchandise or services between the parent company and one or more of its foreign affiliates. An APA takes an average of 20 to 24 months to work out, based on the scope and complexity of the transfer pricing arrangements. The prices are then “locked in” for three to five years under normal circumstances.

Both the company and the IRS are generally motivated to reach an APA, as the benefit to both parties is measured in time and money. Once the APA is finalized, the company must budget resources to:

- File an annual report with the IRS that demonstrates good-faith compliance with the terms and conditions of the APA;

- Calculate compensating adjustments, if any, which are tax reporting alterations made to comply with the terms of the APA; and

- Maintain books and records sufficient to enable the IRS to examine the company’s compliance with the APA.

Among the major benefits of the APA are (1) putting the company in a position that avoids costly transfer price tax-audit examinations, (2) reaching an agreement with the IRS about what information is relevant to the taxpayer’s transfer pricing decision, (3) allowing the company to focus on business concerns rather than defending its transfer pricing decisions, and (4) following the same procedures when a request for renewal occurs.

As long as the functions and risks remain similar to those of the initial APA, the renewal should go smoothly. But sometimes it doesn’t. For example, in 2002, DHL, the package delivery and international courier service company, lost in a transfer pricing scuffle with the IRS. DHL, a multinational based in Germany, encountered a “double whammy” in the case because the U.S. Tax Court assessed a significant penalty for the company’s error in judgment, which involved mainly the value of the foreign trademark rights and unpaid royalties. The lesson here for a multinational company operating in the U.S., or in any other country for that matter, is that due diligence pays off when analyzing the various aspects of its intercompany transactions—particularly those related to setting transfer prices that can be justified in both economic and legal terms.

INVENTORY POLICY DECISIONS

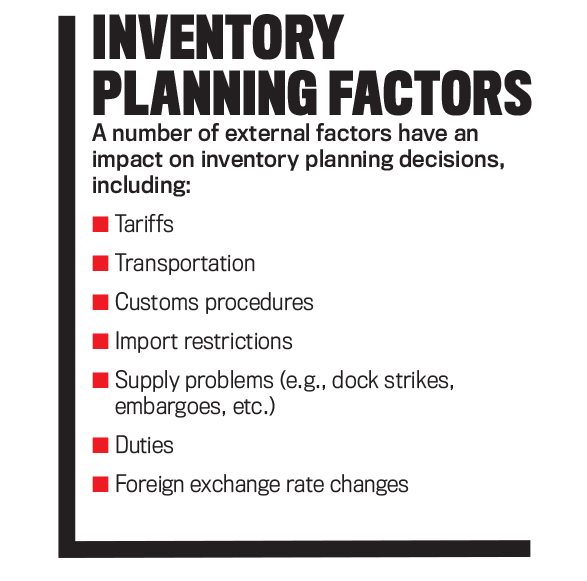

To meet the sales plan, a well-oiled international operation will manage and monitor its manufacturing processes through the production budget. Naturally, a variety of decisions enter into the production plan, including the level of inventory required to minimize costs and stockouts, as well as a number of external factors (see “Inventory Planning Factors”).

Is it possible to counteract the negative consequences of these external factors? To some extent, yes. For example, compare a U.S. computer manufacturer that purchases memory chips from a Japanese firm vs. a U.S. competitor that purchases similar chips from a domestic supplier. The computer producer that uses the Japanese vendor may maintain a higher level of inventory based on events that have occurred in the past (import restrictions, anti-dumping penalties imposed on Japanese suppliers, and devaluation of the U.S. dollar with respect to the Japanese yen) while maintaining an ongoing relationship with other memory chip providers. In this way, the company takes advantage of multiple domestic and international input sources, which is an attractive alternative to putting all of its eggs in one basket.

Besides the impact of external factors, there are other unpredictable or extraordinary events, such as virus pandemics, earthquakes, floods, terrorist acts, and civil disturbances, that might impact the configuration of a multinational company’s inventory policies. Any of these events—or combination of such events—would require altering the advance or delay of inventory purchases. In short, the company may have to maintain a higher or lower level of inventory. Financial managers engaged in the company’s planning process must seek an effective and optimal trade-off between the benefits of the organization’s purchasing policies and the potential costs associated with unexpected disruptions in inventory, similar to those resulting from supply chain dysfunctions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As we’ve seen in 2020, certain inventory policy issues that surfaced during the pandemic were tied to the spike in demand for products such as toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and face masks. At the other end of the spectrum were products that customers either shunned or weren’t interested in, such as luxury goods. The result, in some cases, were price hikes, inventory dumping, and bankruptcy filings by companies such as J.C. Penney, Brooks Brothers, and Lord & Taylor. While plenty of restaurants globally have tried to stay open using takeout and delivery service, it remains to be seen how many of these mainly small, “mom and pop” eateries survive the one-two punch caused by mandated restrictions and people’s reluctance to dine out.

In particular, organizations using the last in, first out (LIFO) inventory system experienced an unexpected dysfunction from the pandemic. As sales and inventory dropped, their cash flow decreased, and their forecasted income taxes increased. One large multinational company that we have knowledge of reported higher profits than expected as it cut into its LIFO layers, creating the worst of all worlds: 2020 revenue being compared to LIFO costs that were very low in comparison to the replacement costs of the items it needed to acquire or manufacture.

THE EFFECT OF TIMING ISSUES

Although current communication techniques have reduced the impact of time lag, factors such as language and cultural barriers, different accounting practices, and time-zone changes can lengthen the time required for a multinational entity to effectively develop its annual budget. The planning process for an international corporation will therefore require a great degree of vertical and horizontal communication and coordination to align its priorities and objectives.

Because of the additional distance and barriers a multinational must face, all of which carry a cost and must be included in the budget, the time required to distribute the budget and discuss it with the appropriate parties will be greater than that required for a domestic company. All of these complications underline the importance of supporting the strategic plan at all levels of the organization, especially those that are engaged in budgeting, and of using time-tested mechanisms to simplify and coordinate the budgeting process.

BUDGET CONTROL

In a global enterprise, steps must be taken to ensure that the control system implemented doesn’t become more complicated than the operation itself. An overly complex system may cast doubt on the multinational’s executives, frustrate middle management, and generally waste a lot of time. In conjunction with this, a multinational parent company must not request information merely because the subsidiary has to pay to provide it. A good approach to reinforce an established company-wide budget control is to implement decentralized control policies that promote decision making at the middle and lower levels of management. At the same time, the multinational parent company should focus on centrally analyzing and monitoring the flow of budget and other important information that the foreign affiliates are required to submit on a timely basis.

A multinational company whose annual profit plan is well prepared and coordinated with its foreign units will find that the plan will lead to effective communication among the parent and foreign operation teams. Thus, the future flow of actual data from the foreign operations and its analysis for control purposes will be facilitated at both the parent company and its affiliate levels. For example, the CFO of a large pharmaceutical company told us that inviting the participation of foreign managers from the outset resulted in short- and long-term benefits for executives of the parent organization and its subsidiaries. One of the major benefits that surfaced was a clear understanding of the strategic reasons for certain actions. Another plus was a greater willingness on both sides of the conversation to discuss constraints and opportunities that occurred after the profit plan was created.

We hear it all the time in business, but it bears repeating in this context: Be flexible. Flexible budgeting is useful for budget control in an international environment where a large degree of uncertainty exists. Many of the uncontrollable influences of the international environment, such as tax rates and spikes in the costs of raw materials, can be isolated to provide a better picture of actual performance. Flexible budgeting allows management to forecast the effects of a variety of scenarios so that alternative actions can be considered and implemented, if necessary.

Here’s a good example: A multinational entity that operates a seafood export operation in Norway, one of the world’s largest exporters of seafood, will prepare three levels of flexible budgets for its upcoming fiscal year (July 1, 2021, to June 30, 2022) based on the following assumptions:

- Trade barriers, including punitive duties and import regulations, won’t become more restrictive.

- More restrictive trade barriers will be put into place prior to the start of the fiscal year.

- Implementation of restrictive trade barriers will occur on or after January 1, 2022.

When evaluating an international operation, performance should be measured based only on areas that the manager controls. If a foreign segment’s management doesn’t control long-term profitability because of organizational or government policies, an alternative evaluation criterion that’s consistent with the multinational’s overall objectives must be selected. Other potential performance measures include market share, sales growth, contribution margins, production costs, inventory and accounts receivable turnover, quality control, or labor turnover. This set of evaluation criteria (and others) combine to become a balanced scorecard.

Finally, a balanced scorecard approach must be consistent with the policies that have been established as a result of discussions with management. When evaluating the performance of an international segment, company executives should recognize that the foreign operation can incur higher-than-expected costs, such as those from above-normal inventory requirements, the effect of different inflation rates on accounts receivable turnover, and local value-added requirements. Performance standards should therefore be tailored to the international segment’s operating environment.

FACTORING IN UNCERTAINTY

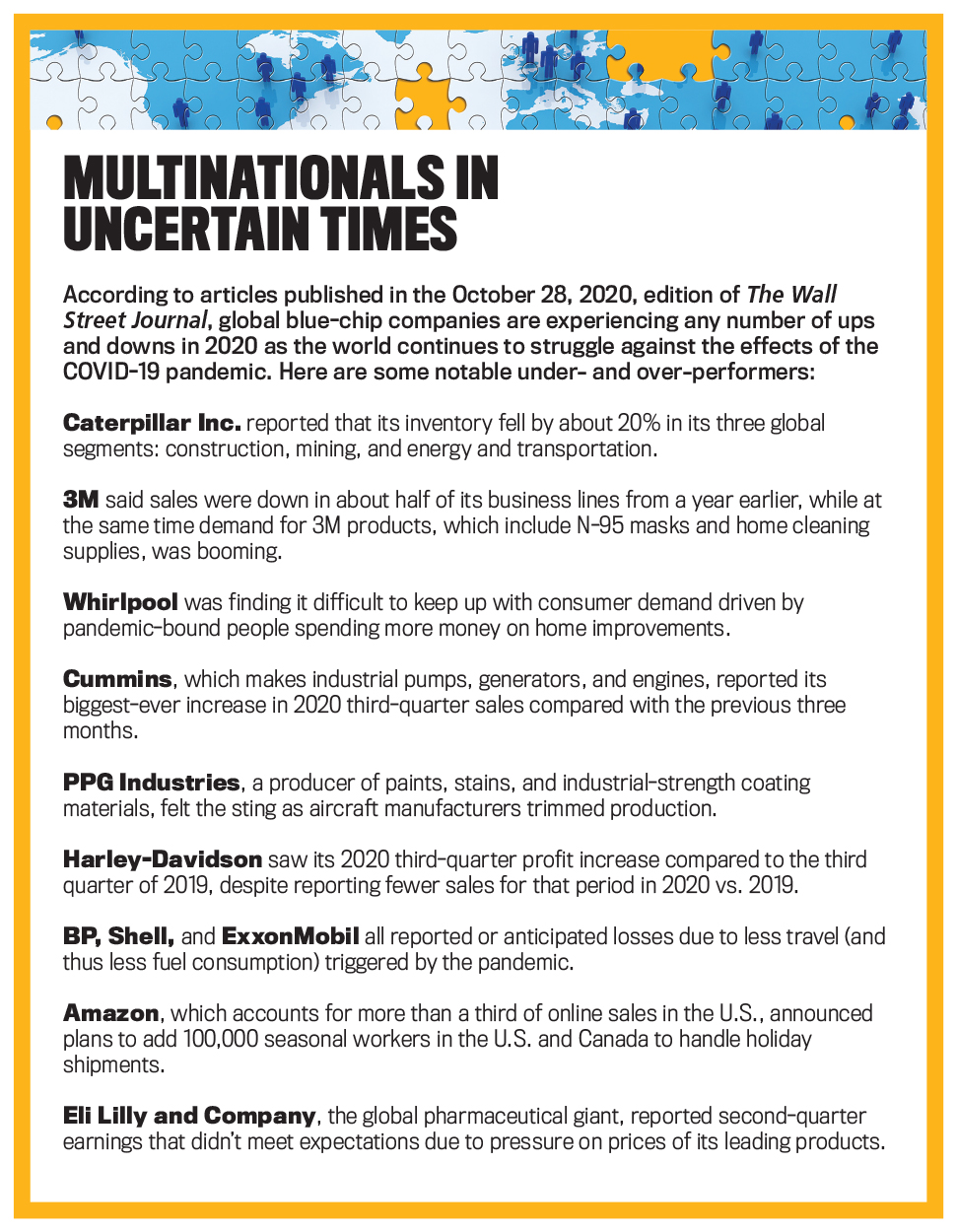

As multinational companies undertake the rigorous business of budgeting for international operations, they must be constantly vigilant and aware of the uncertainty that is a common—and unwelcome—characteristic of any budgetary activity. Any business large or small, whether acting as a buyer, supplier, distributor, producer, or provider of services, is prone to be impacted by factors outside of its control. As the CFOs of the companies listed in “Multinationals in Uncertain Times” can surely attest to, variables such as foreign currency, interest rates, inflation, and even the whims of consumers can singly or jointly affect the target levels of profits and cash flows of companies engaged in global operations.

Recent tariffs and trade war issues, such as those that involve China and the U.S., make it more imperative for business entities to rely on cost containment and to closely monitor their strategic plans and operational budgets. A well-designed, functional, and comprehensive budgeting system is an essential management tool for a multinational business. As we discussed, these companies must forecast the impact of global external variables (like foreign exchange and interest rates) as well as internal variables (transfer prices, supply-sourcing subsidiaries, production sites, etc.). All in all, the budgeting system should be effective not only in monitoring progress compared to plan but also in adjusting to unpredictable events and circumstances.

Financial managers and accounting professionals like yourself are well aware of the multinational and economic environment that you live and work in. Your budgeting and strategic planning efforts continually seek to map and guide your organization’s target profit plans and operational performance. We hope that this series of articles on the management of international operations has provided some tools and insights that may be useful to those of you engaged in planning and control functions in multinational organizations.

January 2021