This article is the second of three in a series on budgeting for international operations. The first article, “Managing International Operations in Uncertain Times,” which appeared in the November 2020 issue of Strategic Finance, identified the general factors and conditions that can impact the foreign operations of a multinational company and hinder its profitability and growth.

This second installment focuses on specific elements—sales, expenses, and capital budgets—and explores the unique challenges of these elements during the strategic planning and budgetary process. (Each article is written for stand-alone reading, but we encourage you to view the three articles as a holistic attempt to provide a productive and useful approach to how multinational organizations engage in strategic planning and prepare their related budgets.)

SALES BUDGETS

When a global business is developing a sales budget, external factors—labor, materials, overhead, and distribution and administrative expenses—can affect the decision regarding which products to market and the product mix. Depending on the type of product the company sells, the market potential, competition, impact of lower-priced substitutes, and market characteristics may be similar throughout a particular region or different in each country. The COVID-19 pandemic and other extraordinary events in recent years, such as terrorist acts, wildfires, and floods, or disasters such as the August 2020 explosion in Lebanon that displaced more than 300,000 people, can trigger uncertain and unfavorable business conditions and affect the nature and volume of international operations.

While these ongoing and unpredictable events are very difficult to incorporate into the annual profit plan, a company must be ready to adjust its approved budget to account for these new circumstances. For example, a multinational company with significant retail and wholesale operations in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico prepares its sales budget each year based on the best estimates and predictions of the effects of natural and climate phenomena such as hurricanes, tropical storms, and even earthquakes.

Of course, the sales budget for a foreign operation is sensitive to the targeted sales territory. Sales budgets for international operations that create products only for intracompany sales are determined by transfer pricing policies. Foreign concerns that produce goods solely for the country in which they reside are similar to most national operations except for the differences in market characteristics, competition, and government regulations. Organizations that market their products in multiple countries, however, must contend with considerations such as tariffs, international trade agreements, import restrictions, and other potential legal constraints.

In the case of U.S.-based companies, the need to quickly adjust and adapt to new tariffs on imports of aluminum and steel was evident in the domestic manufacturing of automobiles and appliances. Likewise, the uncertainties of potential additional duties on imported cars, accessories, and components produced in the European Union and Japan required CFOs of U.S.-based organizations to closely monitor these developments and their potential impact on their companies’ budgets and operations.

Multinationals must be aware of, and respond to, the conditions of each market they serve, including the level of economic development, degree of government price controls, cost of sales, product pricing decisions, available channels of distribution and promotion, and import/export controls. Although these factors are present in every market, selling in multiple markets requires examining each of these elements in order to incorporate its unique characteristics into the strategic plan and sales budgets.

Many of these factors arise from a specific nation’s characteristics, while others stem from international or regional forces. Whatever their origin, they dictate that sales budgets and marketing strategies be developed separately for each market; they can’t merely be transplanted from domestic operations.

EXPENSE BUDGETS

Foreign operations that serve only the local market have expenses similar to those of a multinational’s domestic operations. In this type of situation, most of the production, distribution, and selling expenses will be incurred within one country and may not be adversely affected by foreign currency exchange rates. (For a detailed discussion of the influence of exchange rates, see our November 2020 article.)

External factors, however, and specific government policies controlling economic growth, inflation, interest rates, prices, or costs can influence expense budgets despite the narrow orientation of these foreign operations. Culture, too, can have a weighty effect on budgets, sometimes at a great cost (see “Subtle Influences” at end of article).

Expense budgets must therefore incorporate external forces to depict operations accurately. Native or local managers often will have a better understanding of the foreign market’s potential, availability of local suppliers, conditions of the local economy, and influence of government policies. As such, these personnel may be able to produce more accurate expense budgets than those generated by a nonresident manager or dictated by the multinational company’s corporate headquarters.

For foreign operations that serve large regions (for example, Southeast Asia or South America) or global markets instead of local markets, expense budgets must reflect both internal and external factors. A feasible approach would be to let each of the local managers prepare the budgets for individual countries and assign regional managers to coordinate and modify them to reflect regional factors and the global entity’s strategic plan.

In some countries, brief or surprise labor strikes might disrupt operations and cause potential unexpected costs. Again, these possibilities—in addition to natural or man-made disasters—are a good example of how it can pay to be proactive. In the case of personnel, for example, management must assess whether the labor climate and conditions in the countries where the company operates make it necessary to include in the budget the potential costs of work stoppages or wage and salary adjustments.

Although it’s difficult to predict whether strikes move in the same direction as, or opposite to, business cycles, an astute management accountant can always look at the historical trends and current conditions in the particular place of operations. For example, a research paper on the effect of strikes in South Africa found that, for the decade of 1998-2008, the strike intensity in the country was similar to that in Denmark, Australia, and Iceland. (See Haroon Bhorat, Derek Yu, Safia Khan, and Amy Thornton, “Examining the impact of strikes on the South African economy,” The Mandela Initiative, July 2017.) The authors noted that for that same period, the percentage of strikers’ workdays lost per year was smaller in South Africa than in Nigeria, the United States, Turkey, Brazil, and India, respectively.

The bottom line: Whenever a labor movement affects operations, the resulting expenses should be monitored carefully to ensure they don’t exceed what’s necessary to successfully run the foreign unit given its organizational structure, target markets, input sources, and coordination efforts.

CAPITAL BUDGETING

The capital budgeting process always becomes more complex in a global business environment. The first area of concern involves developing pro forma cash flows that can be viewed from the perspectives of both the domestic and the foreign operation. Developing and evaluating investments using the foreign viewpoint will be especially useful when foreign banks, third parties, and governments are considering investing in the potential project or are evaluating its performance. When assessing a potential foreign investment, the projected net incremental after-tax cash flows that will accrue to the multinational company are derived from those that will accrue to the foreign operation after adjusting the cash flows for fees, royalties, and tax considerations.

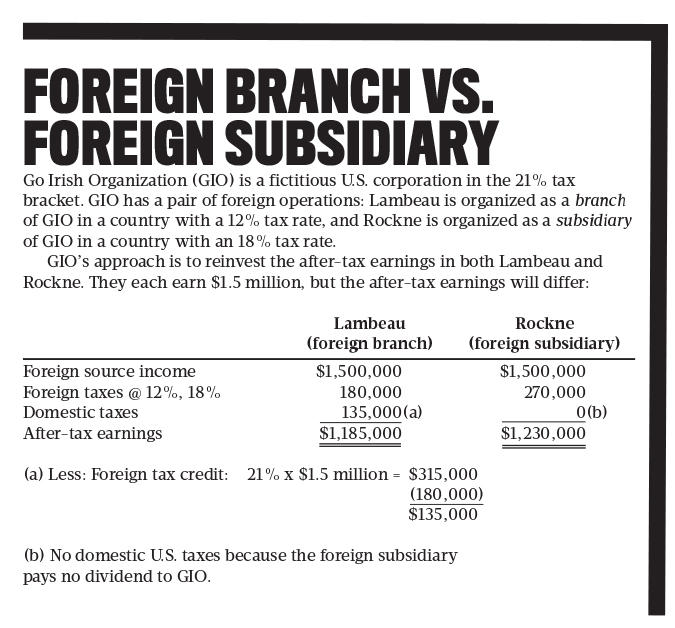

Tax effects between different countries have a significant impact on an investment’s cash flows. For a multinational company, the actual amount of taxes that the parent organization pays is affected by the timing of the cash remittance, the manner of the remittance (loan payments, dividends, transfer pricing regimes, etc.), the foreign income tax rate, withholding taxes, and the form of business established in the foreign country. “Foreign Branch vs. Foreign Subsidiary” provides an illustration of the contrast between a foreign branch and a foreign subsidiary.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Usually, the parent company will pay taxes on any dividends, fees, and royalties it receives from its foreign concerns, but tax treaties between countries may provide for lower taxes or tax credits. For example, the U.S. doesn’t tax royalty, patent, and copyright income from several of its top trading partners, including Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. (For more, see Internal Revenue Service Publication 901, “U.S. Tax Treaties.”)

Another consideration that must be addressed in the capital budgeting process is the weighted average cost of capital to apply when evaluating international investments. This is because the cost of capital that a parent multinational company uses when evaluating an investment in a foreign location differs if the parent company finances the project with its own funds compared to using both the company’s and foreign debt or equity investors’ sources of financing.

Typically, foreign debtors and equity investors would seek different rates of return than the one sought by the multinational parent company. To accommodate for this, the cost of equity capital used by the multinational company should include: (1) the return required by foreign investors weighted according to the percent of their investment and (2) the cost of retaining earnings from the foreign investment, including the tax implications previously discussed. The cost of debt capital must be modified to include the after-tax cost of borrowing foreign currency, if such a source of funds will be used.

These cost-of-capital modifications must be included when developing the weighted average cost of capital used to assess investments in the foreign operation. When evaluating potential foreign investments from the multinational parent company’s perspective, however, the multinational’s weighted average cost of capital can be used to calculate the net present value of the investment under consideration.

In addition to the financial aspects of capital budgeting, the threat of political disturbances or social conflicts adds risk to the value of an international investment. Although this type of risk is present in a domestic setting, management has fewer instruments for preventing or controlling it in a foreign market. Ways to account for such risks in the investment analysis include reducing the minimum payback period, raising the required rate of return, and adjusting the cash flows for the level of risk. The first two approaches are easier to apply, but they average the effects of the potential risk over the entire life of the project; the third approach requires more effort but results in the most realistic projected cash flows. (For a deeper dive into this subject, see Alan C. Shapiro’s Multinational Financial Management, 10th edition, John Wiley & Sons, 2014.)

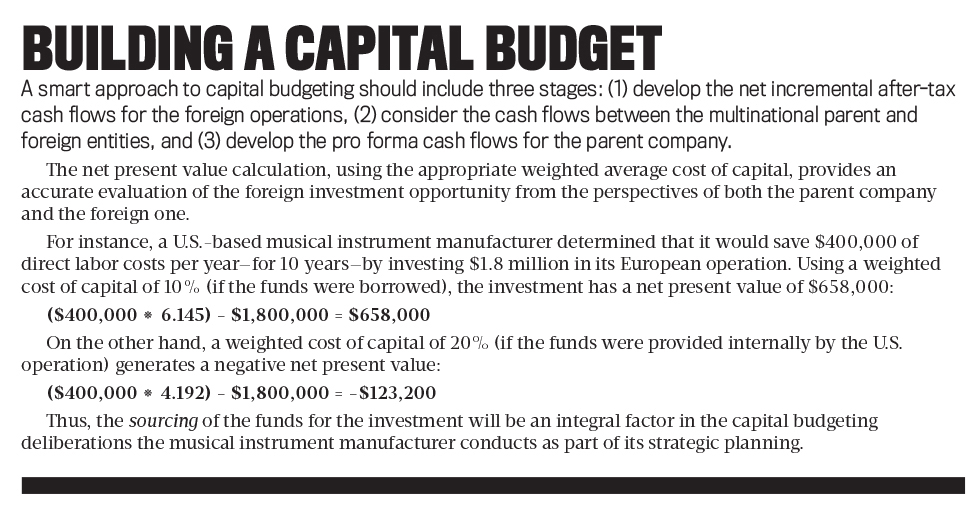

Another factor in capital budgeting for an international operation is the measure of the cost savings the capital expenditure may generate for the multinational company. Consider, for example, a U.S. musical instrument manufacturer that was importing instruments in a semifinished state from its subsidiary in Europe. When the instruments were received, they were disassembled and reprocessed to meet American standards, a process that dramatically cut the company’s U.S.-based direct labor costs. (See “Building a Capital Budget.”)

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

CASH BUDGETING

The long-term objective of cash planning in an international environment is to match cash inflows with cash outflows, thereby limiting the multinational’s foreign currency exposure to only those cash flows (such as profits, royalties, and fees) that will be repatriated from a foreign operation to the parent company. Cash budgeting in combination with capital budgeting can be used to evaluate investments that will manage the parent organization’s long-term economic exposure and match the cash inflows and cash outflows in the same currency.

While seeking to attain the long-term objectives stated in its strategic plan, a global business must also manage short-term cash flows from foreign operations. What appears to be obvious to some managers may not be recognized by all. For instance, we know of an example of a CFO who, as the company made its initial move into an international market, failed to take into consideration that local employees prefer to be paid in local currency. As a result, the employees of the foreign operation were paid in U.S. dollars for the first pay period, creating confusion and generating added costs as the company rectified the oversight. Additional expenses continued for a while due to some changeover charges that the company incurred.

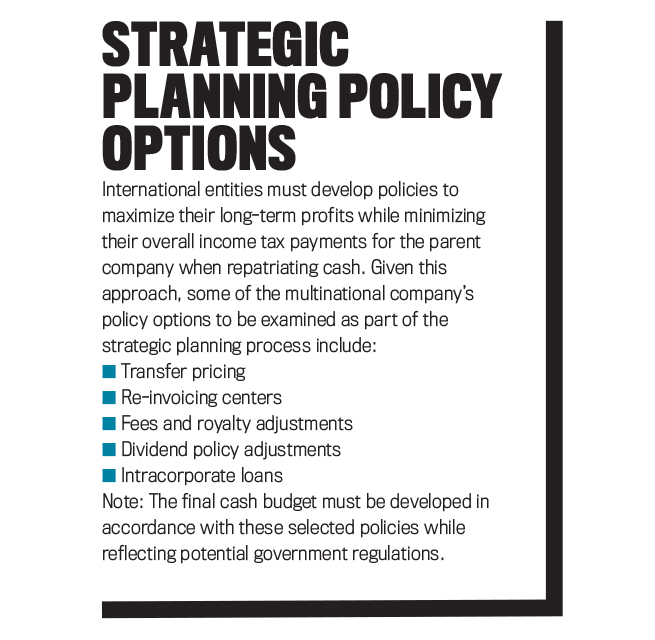

When developing the cash budget, management accountants and other planners on their team must consider currency exchange controls that foreign governments may impose to limit the amount of local or other currency leaving or entering their country during a specific time period. These controls use multiple exchange rates for different categories of goods or services, impose limitations or taxes on specific bank deposits, limit the amount of credit extended to particular companies, govern transfer pricing policies, and/or restrict imports. Normally, multinationals establish consistent policies in their strategic plans that are used throughout the global corporation to indicate an established financial program rather than a speculative repatriation policy that foreign governments may object to. (“Strategic Planning Policy Options” lists policies that multinationals should consider in any strategic plan.)

On occasion, some multinationals may be required to use nonconvertible currencies in order to do business in certain localities. Countries with this type of currency usually prefer or require hard currency inflows and/or countertrade outflows from multinationals to build up their supply of hard currency. For example, as far back as 1990, PepsiCo sold soft drinks to Russia and received Soviet vodka (Stolichnaya) in place of a hard currency payment. (See John-Thor Dahlburg, “Pepsico to Swap Cola for Soviet Vodka and Ships,” Los Angeles Times, April 10, 1990.)

Sometimes countries impose penalties, as Indonesia has done in the past, on companies that don’t participate in countertrade practices. After determining the size and timing of the cash flow for a hard currency transaction, a multinational corporation must adjust the cash budget to reflect either the penalty imposed or the time lag and discount required for the sale of the goods received. Multinationals may offset the effects of countertrade practices by charging a premium for their products or by adjusting the manufacturing and delivery schedules to coincide with the actual sale of the countertrade goods. Planned adjustments such as these are reflected in the sales, production, and other related budgets.

In addition, the overwhelming use of the euro as the official common currency by 16 of the 27 EU countries has implications for cash budgeting. Theoretically, working with a common currency should make the cash budgeting process smoother and more predictable since currency barriers are no longer a factor. Yet the Brexit outcome in the U.K. has created uncertainty and volatility with regard to the value of the British pound and made the budget exercise more complicated for non-U.K. companies with subsidiaries there.

Finally, an effective reporting system is the key to implementing a multinational’s cash budget. Frequent and accurate operation reports will permit managers to adhere to budget policies, monitor the company’s liquidity position, and meet performance targets.

NO EASY TASKS

As you can see, there are myriad moving parts involved in developing an annual budget and strategic plan for an organization with international operations. As a management accounting and finance professional, you’re cognizant that multifaceted budgeting for an international business is becoming more commonplace as the globalization of companies becomes the norm. You may one day be tasked, if you haven’t been already, with working and preparing all of the pieces of your organization’s annual budget for mapping and controlling its multinational business operations. And if unpredictable or extraordinary situations develop—like the COVID-19 pandemic—you need to be ready to revise and adjust these budgetary elements and plans so as to better help steer and correct the course of the business.

In the third and final installment in this series, we’ll look at transfer pricing, inventory policy decisions, timing issues, and budget control, with an emphasis on the uncertainty involved in budgeting—all of which, when taken together with the information covered in the first two articles, can best equip you to handle the challenges of managing the finances of an expanding multinational company in the coming months and years.

Subtle Influences

Not all external factors are readily apparent. Cultural factors, for instance, can have a strong influence on budgets in a particular country or region.

For example, a few years back an appliance manufacturer spent a considerable amount of money demonstrating and promoting its products in China. When sales came in well below expectations, the manufacturer’s sales team asked around and eventually found out why: All of the appliances were white. In China, white is sometimes associated with mourning and death. From a budgeting standpoint, it cost millions of dollars for the company to replace the inventory and thus overcome the cultural barriers. But from a business standpoint, access to a market as large as China’s more than justified the additional spending.

In another example, a U.S.-based computer hardware manufacturer that had been shipping its products overseas for a long time discovered that the packaging used for its shipments to Brazil was inadequate for items being sent to India because of differences in infrastructure between the two countries. In fact, every shipment to India wound up damaged in some way. The company responded by adding more protective padding and changing the shape of its shipping boxes.

Finally, when it comes to labor, multinational companies need to consider that an unskilled, unmotivated workforce normally means higher turnover, excessive costs, and lower labor productivity. When comparing direct labor budgets between operations in different countries, it’s therefore important to review relative characteristics such as productivity rather than actual characteristics such as total direct labor costs. Generally, multinational companies have shown their skill in adapting and altering their strategic plan and adjusting to new international conditions in a practical and functional manner. Their operating budgets consistently reflect this flexibility.

December 2020