WHAT DO PEOPLE ACTUALLY DO?

Traditional ethics focus on what people should do. But the burgeoning field of behavioral ethics explores what people actually do.

That’s a big difference, and it came about because the old approach didn’t work well. Ann Tenbrunsel, professor of business ethics at the University of Notre Dame, asserts that “…efforts designed to improve ethical behavior in the workplace continue to over promise and under deliver.” (See http://bit.ly/1cXD5R7.)

Those efforts fail partly because we all have unconscious ethical blind spots. In “Stumbling Into Bad Behavior” in the April 21, 2011, issue of The New York Times, Max H. Bazerman and Tenbrunsel wrote that “…we have found that much unethical conduct that goes on, whether in social life or work life, happens because people are unconsciously fooling themselves.” (See http://nyti.ms/1EGRRlV.)

Management accountants are becoming more aware of the bias problem. In 2012, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) published a report by KPMG LLP, Steven M. Glover, and Douglas F. Prawitt, “Enhancing Board Oversight: Avoiding Judgment Traps and Biases” (see http://bit.ly/1bS5zdy). And a 2011 KPMG monograph, Elevating Professional Judgment in Auditing and Accounting: The KPMG Professional Judgment Framework, also dealt with accounting judgment issues (see http://bit.ly/1e3eJpd).

Both documents show that the accounting profession realizes that flawed decisions result from not following a sound judgment process. Management accountants also need to know that group decisions that aren’t structured and conducted properly can make judgment traps and biases worse.

WHY DO BIASES THRIVE IN ACCOUNTING?

Accountants can have the best ethical intentions and believe they are meeting their responsibilities with competence and integrity. But there are known cognitive biases that can make them fall short. Unfortunately, corporate accounting and auditing are particularly prone to self-serving biases.

In their December 9, 2002, online article for Harvard Business School, “Most Accountants Aren’t Crooks—Why Good Audits Go Bad,” Bazerman, George Loewenstein, and Don A. Moore identified three structural aspects of accounting that create opportunity for self-serving biases (see http://hbs.me/1JKzNdW). First, biases thrive when there is ambiguity. Although some accounting decisions aren’t ambiguous, many require considerable judgment—such as classifying an item as expense vs. capital, deciding when to recognize revenue, or estimating allowance for doubtful accounts.

Second, accountants have self-serving reasons to go along with their bosses’ or clients’ preferences. Psychologists refer to this as attachment. It’s well documented that self-interest unconsciously biases decisions.

Third, as Bazerman and his colleagues note, research affirms that judgments become even more biased when people endorse others’ similarly biased judgments. Psychologists call this condition approval. It especially can apply to external auditors, internal auditors, and financial analysts gathering evidence and expressing agreement or disagreement about proposed financial statements, budgets, or forecasts.

Our Bias-Boosting Nature. Bazerman, Loewenstein, and Moore also describe three tendencies of human nature that amplify unconscious decision bias. The first one, familiarity, means we are more willing to harm strangers than those with whom we have an ongoing relationship. The second, discounting, means that we weight immediate decision consequences more heavily than future consequences. The third tendency, escalation, means that we are more apt to ignore wrongdoing if it starts small and gradually escalates. This last tendency can provoke unconscious bias to evolve into conscious corruption or fraud—often despite our best intentions.

Regulators sometimes acknowledge this fact. In their article, Bazerman and his colleagues quoted then Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) Chief Accountant Charles Niemeier, who said: “People who never intend to do something wrong end up finding themselves in situations where they are almost forced to continue to commit fraud once they have started doing this. Otherwise, it will be revealed that they had used improper accounting in the earlier periods.”

Our Two Reasoning Systems. Unfortunately, judgment traps and biases have a greater effect on the decisions of competent, well-intentioned people than we realize. That’s because researchers have found that we actually have two different reasoning systems in the brain, and sometimes we use the wrong one. Pioneering psychologists Keith E. Stanovich and Richard F. West named these reasoning processes “System 1” and “System 2” in their October 2000 article, “Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate,” in Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

System 1 is automatic, mostly unconscious, fast, intuitive, and context sensitive. It’s social in nature and is an evolutionary adaptation like our fight-or-flight instinct. System 2 is analytical, rational, based on rules, slow, not social in nature, works to achieve our goals, and is consistent with our beliefs.

System 1 reasoning comes into play when we make quick routine decisions like watching for traffic when crossing the street or moving away from signs of danger. Going through the day, it would be extremely time-consuming to apply analytical thinking to the hundreds of routine decisions we must make—such as what route to take to work, when to apply the brakes, when to use a turn signal, or when we should drink water.

We use System 2 thinking best for making thoughtful business decisions—such as choosing a raw materials supplier or what to accrue for obsolete inventory. But the more experience a decision maker has, the more he or she tends to rely on System 1 thinking. The judgment trap is that managers may rely on System 1 thinking in situations where System 2 would be more appropriate.

FIVE KEY JUDGMENT STEPS

Talent and experience are key components of effective judgment. But consistently following a proper judgment process enhances judgment skills for both new and experienced accountants.

According to the COSO report and KPMG monograph mentioned earlier, key elements of a good judgment process include having the right mind-set; employing consultation, knowledge, and professional standards; being aware of influences and biases; and making use of reflection and coaching.

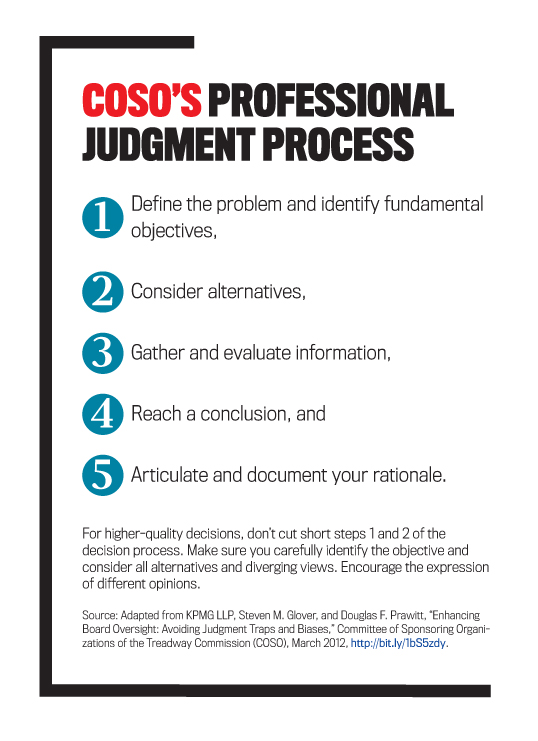

What does a good, professional judgment process look like? The five key steps are listed in “COSO’s Professional Judgment Process.”

Notice that the first step is to define the problem and identify fundamental objectives. Don’t assume everyone knows what they are and that you can skip the first step! Not properly defining the problem leads to a judgment trap called solving the wrong problem and wasting time. If you don’t define the problem accurately, you could be influenced by a judgment trigger rather than a clearly defined decision objective. That’s what happens when we underinvest in defining the fundamental issue.

Although the judgment process seems simple and intuitive, in the real world we encounter pressures, time constraints, limited resources, judgment traps, and self-interest biases.

AVOIDING JUDGMENT TRAPS AND BIASES

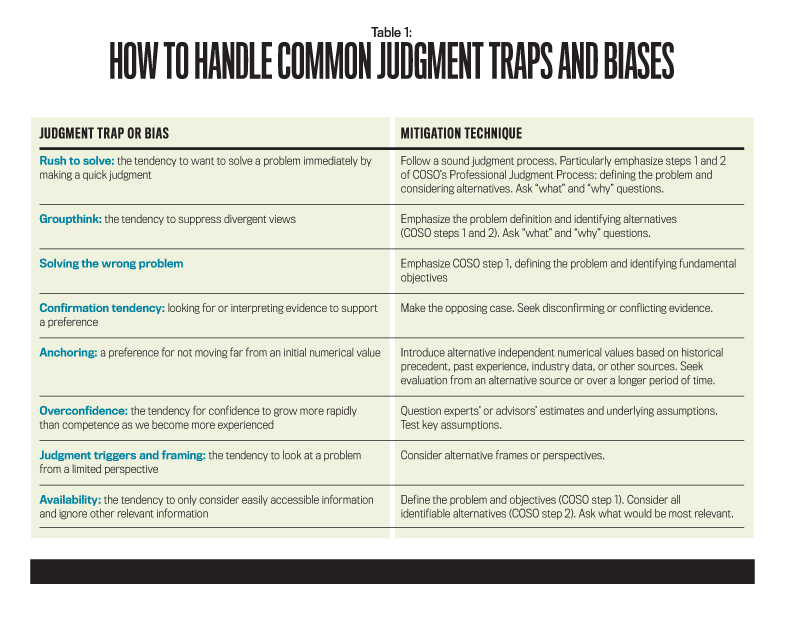

It takes hard work to avoid judgment traps and biases. For a list of the most prominent ones and how to handle them, see Table 1. Unintentional biases arise from using mental shortcuts, which are the results of System 1 thinking. Although these shortcuts are efficient and effective in some situations, they often result in predictable bias. When you cross the street in the United States, you automatically look to the left for oncoming traffic. This is an efficient and effective automatic response. But if you cross the street in the United Kingdom, where they drive on the opposite side of the road, this automatic response could lead to damaging consequences. Once you understand the implications of a shortcut, you can take measures to mitigate its impact. But you should be aware that mitigation is difficult and often has only a limited effect. City planners in London paint directions on the streets and take other measures to remind tourists to look to the right as well as the left when crossing the street.

To make quality ethical decisions, it’s important for you to have an appropriate mind-set: an inquiring mind that analyzes objectives, information, and alternatives to reach a conclusion. But you must do all that objectively, critically, creatively, and somewhat skeptically.

Now let’s follow a hypothetical CFO throughout her workday to show how hidden judgment triggers and biases affect her ethical decisions and what she can do about it.

A CFO’S PITFALLS

Julie Smith is the CFO of a midsize manufacturing company. It’s Friday, and many things are happening at once. Today is the end of the company’s second quarter, she is finishing the last round of her staff evaluations, and she has to give Human Resources (HR) her final decision on the new hire for the controller’s office. Instead of looking forward to a relaxing weekend, she’s worried about tomorrow’s emergency board meeting to approve the acquisition of the company’s main raw materials supplier. In addition, her children’s spring school break starts next week. Her whole family plans to get up early on Sunday and fly to Florida for a vacation.

Julie is a CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) and a member of IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants). She diligently tries to follow the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice (see http://bit.ly/IMAStatement). But even if Julie were aware of all of her decision biases, behavioral research shows that it’s difficult or impossible to eliminate them! Like most executives, Julie has little formal training in psychology, in how to make good judgments, or in how to spot human tendencies that threaten good judgment. Her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in accounting focused on technical knowledge needed to pass the CMA and CPA (Certified Public Accountant) exams. And her MBA focused only on managing change and strategic planning.

Julie has several important decisions to make before leaving on her vacation. This artificial deadline could lead to the judgment trap called rush to solve (see Table 1). Because she is rushed, Julie might not adequately consider all the job candidates and their qualifications before making a hiring decision. If she knows the previous salary of a job applicant, Julie’s salary offer may be affected by a bias trap called anchoring—a preference to stay close to an initially named numerical value. Knowing the candidate’s salary before the candidate earns an MBA may cause Julie’s offer to fall short of what the candidate is really worth now.

The emergency board meeting presents other problems. Julie, the CEO, and the board chair are all urging the acquisition of their raw materials supplier for a price of $600 million. But business decisions made in a group setting like the board meeting can be biased because participants often suppress divergent views. In this case, no one wants to disagree with Julie and the CEO. The board doesn’t encourage people to voice different opinions, which results in shallow thinking.

Also, the board may mistakenly believe that an early consensus is a sign of strength. It may not spend enough time defining the problem, clarifying issues and objectives, or considering alternative actions.

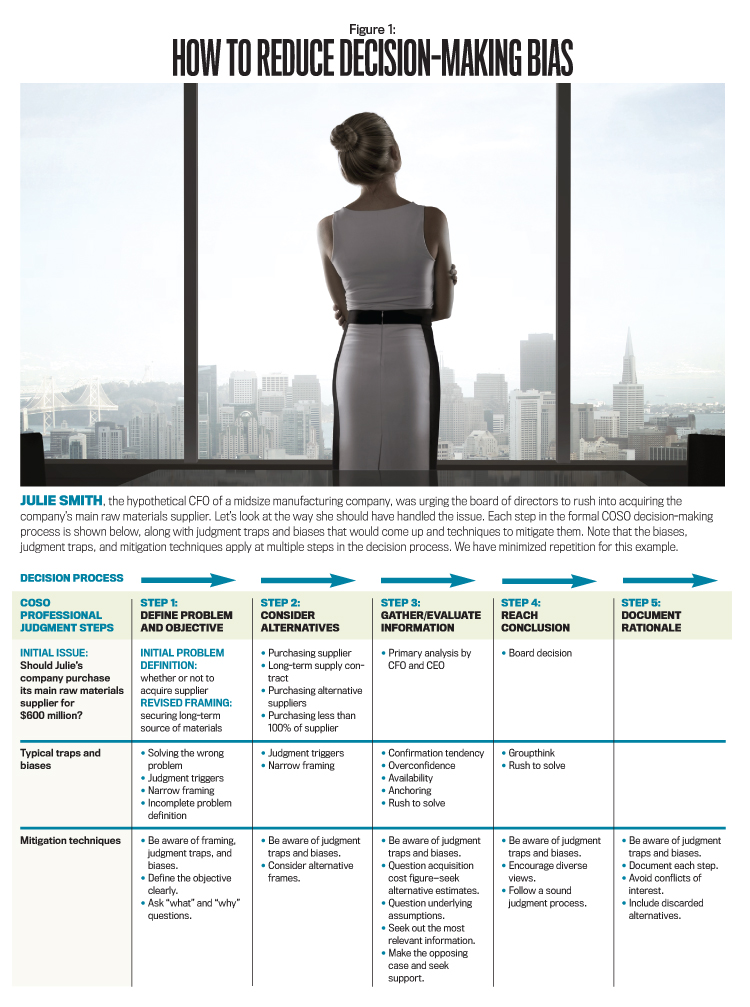

To see how Julie should have handled the acquisition issue using the COSO Professional Judgment Process to reduce decision-making bias, see Figure 1.

DON'T LIMIT PERSPECTIVES

At the emergency board meeting, Julie presented the potential acquisition as a “slam dunk” move with low risk. But she didn’t present any alternative viewpoints. That’s a red flag!

Julie needs to understand the concept of frames—mental structures or perspectives used to determine the importance of information. Imagine you’re in a house where each window gives you a different view. By considering all the windows—the frames—you get a better understanding of where the house is situated. Julie considered only one frame—that the acquisition was a “slam dunk.” Better decision makers are aware when they are dangerously limiting the number of frames.

The board made this problem worse by not defining its objectives carefully. Is the objective securing a long-term source of raw materials? If so, did the board consider other actions—such as a long-term supply contract, purchasing alternative suppliers, or purchasing less than 100% of the current supplier? The board’s narrow framing of the issue creates a judgment trigger. Executives pounce on one action but not necessarily the best one. As the KPMG monograph notes, studies show that we become more confident as we become more experienced and successful. But our confidence actually increases more rapidly than our competence. If board members realized this, they might be more skeptical of the “slam dunk” recommendation.I'VE MADE UP MY MIND

We all know people who say, “Don’t bother me with the facts. I’ve already made up my mind.” This attitude illustrates our unconscious confirmation tendency. We tend to look for evidence confirming our viewpoint instead of being evenhanded. If board members are pressured into accepting Julie’s viewpoint, their research may turn up supporting data only.

And the fact that Julie has already suggested it will cost $600 million to acquire the supplier makes the board vulnerable to the anchoring judgment trap—our tendency to not move far from an initially named numerical value. So even if buying the supplier is a good idea, Julie has biased the board to spend about $600 million on it.

But what if Julie didn’t name a figure and assigns someone to investigate the supplier? The researcher finds that the supplier has been profitable for the past 10 years but that some older, difficult-to-find information hints at major unsolved problems. In that case, a judgment trap called availability might trip up both the researcher and the board because there’s a tendency for decision makers to consider information that’s easier to retrieve as being more relevant to a decision than less accessible information. Auditors can fall prey to this trap also. An auditor may follow an approach used in previous years or on a recent engagement even if other approaches may be more effective. Our “desires” heavily influence the way we interpret information.

In addition to considering alternatives, the way the board examines them can bias a decision. The board should consider multiple options at the same time rather than one option at a time. If options are considered consecutively, there’s a tendency to approve a suboptimal option and then not give equal consideration to other options, according to Kathrine L. Milkman, Dolly Chugh, and Max H. Bazerman in “How Can Decision Making Be Improved?” in Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Julie and the board also should consider all stakeholders’ points of view. As Julie documents her conclusion, she should assess whether it makes sense and whether the underlying information supports it.

Thus Julie and the management team are facing judgment traps and unconscious biases in a variety of areas. But the biggest problem is that they aren’t even aware of them.

REDUCING BIAS

The good news is that everyone can start reducing bias with four simple steps:

- Follow a sound judgment process,

- Be aware of judgment traps and biases,

- Reduce conflicts of interest, and

- Try to recognize situations causing vulnerability to bias.

Then you have to follow up and continue to work at it. Behavioral research consistently demonstrates that being aware of judgment biases is only a first step in reducing their effects. Even with awareness, it’s very difficult to overcome biases. And other things can bias our decisions, such as anger, tiredness, stress, and how many issues we handle at the same time.

But working on this will pay big dividends. By following a sound judgment process, you can replace knee-jerk reactions with formal analysis. That’s the way to make your everyday ethics excel and protect yourself, your company, and all its stakeholders.

June 2015