CURRENT CONSIDERATIONS

Effective RM/IC supports management’s attempts to make all parts of an organization more cohesive, integrated, and aligned with its objectives while operating more effectively, efficiently, ethically, and legally.

Risk can be defined as “the effect of uncertainty on setting and achieving objectives.” This suggests that organizations should focus primarily on setting and achieving their strategic objectives and then, based on those objectives, focus on how they should manage the related risks. Employing a correctly developed RM/IC framework is an integral part of an organization’s management system.

Some organizations haven’t yet established a framework for formally managing risk, relying instead on ad hoc crisis management. Others have implemented some sort of RM/IC framework, but many such frameworks are plagued by serious flaws, such as:

- Having a compliance-only mentality. Many organizations cover the basic issues, such as formal roles and responsibilities, prevention and detection of fraud, and compliance with laws and regulations, but they ignore the need to address both the compliance and performance aspects of risk management.

- Treating risk as only negative. Too many managers overlook the idea that organizations actually need to take risks when pursuing their objectives. Effective risk management enables an organization to exploit opportunities and take on additional risk while staying in control and thereby creating and preserving value.

- Internal control that’s overly focused on external financial reporting. Implementing internal controls over financial reporting is important in the detection and prevention of fraud, as well as in ensuring that financial reports are accurate and may be a major focus for corporate regulators. Effective controls, however, should address all material risks to help organizations achieve their objectives, create value, and avoid loss.

- Regarding risk management as a separate function or process. Line managers should be aware that they are managing risk as part of their everyday roles and responsibilities in line with an organization’s intentions as expressed in its policies, goals, and objectives.

- Governing bodies not living up to their own risk management policies. Boardroom dynamics and the tone and action at the top play important roles in ensuring that effective risk management occurs throughout organizations.

ASSESSING RM/IC MATURITY STAGES

Because most companies typically think of what might either facilitate or prevent the achievement of organizational objectives when they decide how to best execute them, some form of RM/IC already will be “integrated” into most organizations. But if the approach adopted isn’t coherent, consistent, or comprehensive, its outcomes are likely to be unreliable.

Figure 1 shows a typical pathway many organizations follow when they develop their stages of risk management.

An organization’s RM/IC maturity stages can be summarized this way:

- Nonexistent or ad hoc—often characterized by reactive crisis management once something has gone wrong.

- Internal control only—formal internal controls, often focused mainly on external financial reporting.

- Stand-alone risk management and internal control—functioning as a siloed system next to, and not necessarily in tandem with, an organization’s management system.

- Integrated risk management—including internal control, which is a natural and integral part of an organization’s system of management.

Although many organizations advance through these RM/IC maturity stages over time, ideally they should integrate risk management, including internal control, into their management systems from the start. For example, they can get a good grip on assessing the maturity and effectiveness of their RM/IC arrangements by comparing their own performance with good practice developments by looking at recent audit results and analyzing any serious flaws identified during the audits. And organizations such as the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) have created RM/IC frameworks and guidelines (see RM/IC Frameworks and Guidance on p. 38) to help organizations in their journey of continuously evaluating and improving their RM/IC arrangements.

A CASE STUDY EXAMPLE

Are COSO’s Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework, the ISO’s Risk Management standard, and other available guidance truly useful in practice? Or do they merely represent conceptual ideas or theoretical best practices that have limited practical value in the real world?

We believe they are legitimate tools to be applied in the normal course of business, whether informally or in a comprehensive, structured way. The following case study, based on the experiences of a company involved in co-manufacturing, shows how to use the COSO Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Framework to manage a co-manufacturing network more effectively. Co-manufacturing is a manufacturer’s use of another company or third party to manufacture or package a product.

SETTING THE STAGE

The consumer goods industry, especially food and beverage companies, is becoming increasingly competitive. Consumers can choose from a large and growing variety of products—branded or private label—in any local grocery store. Looking to buy a simple meal? Consider gourmet soups, frozen pizzas, ready-to-serve cultural dishes, or even complete, fresh meals. Are you thirsty? Try green teas, exotic fruit juices, vegetable-based beverages, coconut waters, or natural energy drinks. The diversity of choices is amazing.

Some consumers decide to buy a given meal or beverage based on convenience, choosing ready-to-eat products or those requiring limited preparation. Others want to make healthy choices, using products that contain a full serving of vegetables, or try to address dietary restrictions, selecting low-sodium or gluten-free items. Or the critical factor may be package size, whether multi-serve options for a large family or single-serve options for those who live alone. And, of course, price is a consideration.

For food and beverage companies, innovation is critical to ensure their products stand out from the competition. Steadily evolving innovation can enable product reformulations and/or line extensions, ensuring a brand remains fresh and meaningful to its consumer base. Disruptive innovation, on the other hand, enables development of entirely new and different products, even new product categories.

THE CO-MANUFACTURING SOLUTION

To leverage innovation effectively, a company must be able to quickly translate its innovative ideas into on-shelf product offerings. To accommodate innovative new products, a company’s supply chain must be agile and flexible, which can be a potential challenge for companies with significant capital investment and well-established manufacturing processes. The greater the change to existing products—whether in terms of recipe/formula, size, process, or packaging format—the greater the potential “pain” for existing manufacturing systems, especially if these systems are already constrained.

For many food and beverage companies facing this dilemma, the answer is to work with third-party co-manufacturing partners. Specifically, they engage contract manufacturing and co-packing partners to support initiatives when they don’t have the capability and/or the capacity internally. For example, if a tomato sauce company can partner with a co-manufacturer that already has the equipment to process cream-based sauces, it can test its innovative ideas while mitigating the risk of making an unnecessary investment if the initiative doesn’t produce good results.

MANAGING THE CO-MANUFACTURERS

Managing a network of co-manufacturing partners consists of several key processes. The most obvious process, especially if you’re working with co-manufacturing partners for the first time, is to identify and select the right partners and then enter into solid agreements with them. When dealing specifically with food and beverage co-manufacturers, it’s essential to conduct supply chain quality assessments, tightly manage recipes/formulas, and ensure the partners have effective product recall capabilities.

To effectively monitor the cost aspects of co-manufacturing, the outsourcing parties must define meaningful cost standards and then continually compare the partner’s results against these standards. They may also need to control finished product inventory and, potentially, raw materials and/or goods-in-process, depending on how their agreements are structured. Likewise, outsourcers may need to provide oversight when their co-manufacturers make capital investments on their behalf.

Finally, outsourcing parties should implement effective risk management and business continuity planning (BCP) and require co-manufacturers to develop, implement, and periodically test similar plans, especially if a co-manufacturer represents the sole source for an essential product offering.

APPLYING THE COSO ERM FRAMEWORK

As a company’s business model and environment change, management must rethink and refine the organization’s governance and RM/IC arrangements. If a company decides to augment its manufacturing capability with one or more co-manufacturing partnerships, management should update the related governance and RM/IC strategy and activities accordingly. Using the COSO ERM Framework is a good way to do this.

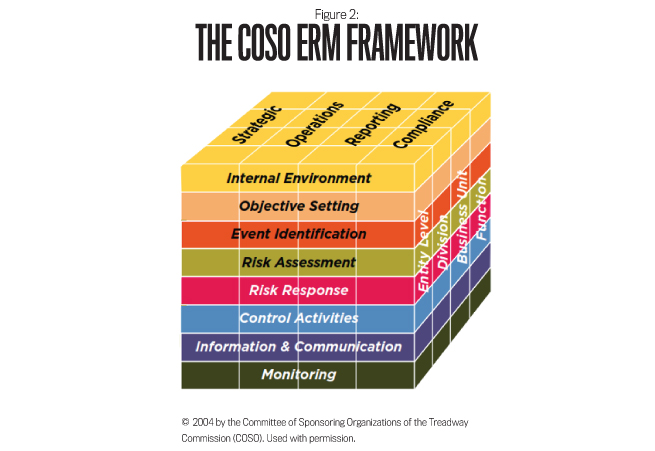

Entity Structure

The COSO ERM Framework is adaptable to a company’s structure. It can be applied at the overall organizational level or at a subsidiary, divisional, operating unit, and/or functional level.

For the co-manufacturing operations of a food or beverage company, the relevant entity structure for applying the COSO ERM Framework is that of an operating unit. To the extent that global functions also support the co-manufacturing operations, such as research & development, quality, legal, and/or procurement, they should also be considered part of that operating unit.

Objectives

The COSO ERM Framework is geared toward achieving strategic, operational, reporting, and compliance objectives. In the context of managing a network of co-manufacturing partners, each of these distinct but overlapping categories of objectives is relevant:

- Strategically, management may want to drive significant growth via innovative new products that are beyond the company’s current capability and/or capacity. Partnering with a specific co-manufacturer may enable the company to overcome this barrier.

- Operationally, management’s goal is to deliver high-quality products to consumers at an appropriate price point while delivering an acceptable profit margin. Specific operational objectives may address productivity, quality, inventory control, customer satisfaction, consumer complaints, financial, and other metrics.

- To oversee its co-manufacturing network effectively, management should establish internal reporting objectives that include key performance indicators (KPIs), financial reporting, and other insights.

- From a compliance perspective, the objective is to conduct co-manufacturing operations in accordance with external laws and regulations, as well as with the company’s own established policies and procedures, including periodic mock recalls, recipe/formula management, and development of business continuity plans.

Components

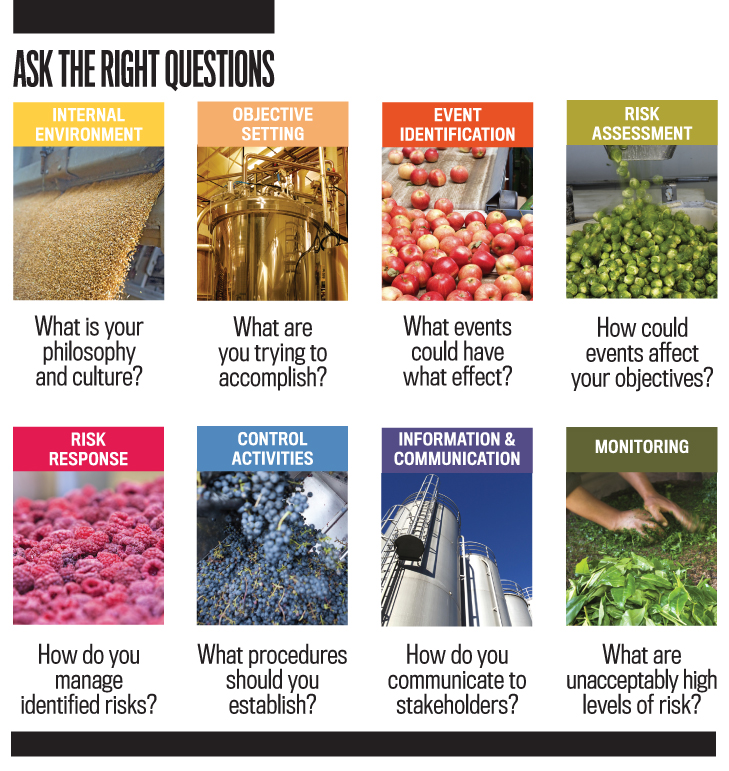

The COSO ERM Framework consists of eight interrelated components (see Figure 2). To manage risk related to establishing and operating a company’s co-manufacturing network, you should analyze each component in an iterative manner.

Internal Environment. Relevant questions here are: What is your internal philosophy and culture? Is senior management setting the appropriate tone for the cross-functional team managing the company’s co-manufacturing network? And is this tone flowing out to your co-manufacturing partners? Is your organizational structure conducive to effectively managing a network of both internal and external manufacturing sites? Are the individuals who manage the co-manufacturing relationships competent, and do they possess the appropriate executive power? Finally, are accountability and performance driven by appropriate measures and incentives?

Objective Setting. Setting suitable objectives is a prerequisite to identifying the sources of risk that would prevent you from achieving them. Therefore, you have to ask yourself what you’re trying to accomplish. As we noted, the typical main objective of co-manufacturing is to rapidly expand capacity without significant capital investment. Other co-manufacturing objectives could be to address supply chain capacity issues when the demand for a given product surges unexpectedly or to optimize production costs for low-volume, short-run products. Each of these objectives generates unique opportunities for and threats to their achievement.

Event Identification. Are there any internal and external events that could have a detrimental or a positive effect on the achievement of your objectives? For example, what events could have an impact on the business continuity of a co-manufacturing partner, and how would they affect the collaboration? Does the co-manufacturer have a diversified customer base, or is it overly dependent on one or two customers? Does it have a solid cash flow? Does its leadership convey the appropriate tone regarding acceptable business practices and ethics? There also might be opportunities arising from a partner in financial distress, such as being able to acquire products or processes at fire sale prices.

Recipe/formula management and product quality are very important to food and beverage products. You need to think about what could possibly go wrong when sharing a top-secret recipe with a co-manufacturer or when you have to deal with frequent formula changes. And what could prevent your partner from consistently delivering high-quality products that are safe for consumption?

Risk Assessment. Once you’ve identified the potential events—either negative or positive—you need to determine the resulting level of risk: How could these events affect your co-manufacturing objectives? What’s the likelihood they will occur?

When assessing potential co-manufacturing partners, management may want to put together a cross-functional team, including process safety, quality assurance, research & development, engineering, package engineering, financial, and other experts, to conduct multidimensional due diligence. In some cases, the team may need to vet several viable partners. In other cases, especially when dealing with highly innovative products that require unique or cutting-edge technology, there may be just one option.

If management selects a financially solid co-manufacturing partner with a professional leadership team, proven technologies, best-practice process safety protocols, and stringent quality checks, the risk of continuity or quality issues occurring is typically low. But contracting with such a solid partner will come with a premium, which might be a risk to achieving the required cost efficiency. If management decides to partner with a low-cost but poorly funded start-up with untested equipment and limited manufacturing experience, the risk of business continuity or product quality issues increases exponentially. So there’s a balance to be struck between the various variables, taking into consideration the options the company has for managing the resulting risk.

Risk Response. What can you do to manage the identified risks? What are the options?

Continuing with the previous example, where the only option is to partner with a low-cost but unstable co-manufacturer, management may decide to avoid the risk outright. Specifically, it may decide that the risk that the co-manufacturer will produce inconsistent and/or poor-quality products outweighs the potential reward of bringing highly innovative new products to market.

On the other hand, the company may decide to accept, reduce, share, or even increase the risk. If management is comfortable with the co-manufacturer’s processes and procedures, even though they are relatively untested, or it believes that the potential reward far outweighs the risk, it may decide to accept the risk without taking many additional precautions.

To further reduce the risk, management might ask the co-manufacturer to add additional quality-control checks to its processes and/or implement its own quality reviews before releasing the product for sale. In addition, management could consider launching the new product in a regional test market rather than immediately going national or global to ensure that the co-manufacturer is truly capable of meeting its contractual obligations.

To share the risk involved in bringing a new product to market, management could buy business interruption or other appropriate insurance coverage. Or it could enter a joint venture with another company working on a similar innovation.

Finally, management may decide to exploit the risk, turning risk into opportunity. For example, if a certain partner is a poorly funded start-up, it may own patents to cutting-edge technology that will transform some aspect of the manufacturing or packaging process. To that end, management may want to invest in the co-manufacturer and support it in marketing this technology across the industry. Or management might offer to acquire the co-manufacturer.

Control Activities. What policies and procedures should you establish to manage the risks identified? For example, to address the co-manufacturing risks related to financial stability, product quality, formula management, and business continuity, management could implement the following control activities:

To ensure financial stability, perform a preliminary financial review before partnering with a co-manufacturer. Then rely on annual reports, Dun & Bradstreet reporting, and other such tools to regularly monitor financial stability.

Mitigate the risk of receiving inferior products from co-manufacturers by establishing well-defined policies and then conducting periodic quality system audits at each partner’s location. Even so, inferior products could make it to market. To ensure such products can be retrieved quickly, initiate monthly or quarterly mock recalls, and require co-manufacturing partners to carry out the recalls in accordance with predefined parameters.

Require co-manufacturing partners to confirm receipt of new recipes/formulas and the destruction of obsolete ones in both hard-copy and electronic format to enforce appropriate recipe/formula management.

Prepare an annual overall business continuity plan for all co-manufacturers, including a risk assessment of each co-manufacturing partner. Based on the outcomes of these reviews, consider requiring essential co-manufacturing partners to create and maintain customized business continuity plans.

Information & Communication. How will you obtain information and communicate with all relevant stakeholders? What information is important to enable your cross-functional managers and employees directly involved with co-manufacturing activities to carry out their responsibilities, including managing the risk to meeting their objectives?

Working with a co-manufacturing partner presents unique challenges, especially if the partner is geographically distant or there are significant language and/or cultural barriers. The more partners you have in the network and the more complex the related agreements, the more these challenges are amplified.

To facilitate effective communication and information flows, management could, for example, assign each partner an internal relationship manager, create standardized operational and financial reporting, and host cross-functional meetings to ensure alignment.

Monitoring. Identification of unacceptably high levels of risk, control failures, or events that are outside the limits for risk taking can be a sign that your controls are ineffective and need improvement, which marks the start of a new risk management cycle.

In addition to cross-functional alignment meetings with individual co-manufacturing partners, using standardized reporting and dashboards, and making periodic on-site visits, management could conduct quarterly business reviews that encompass the entire co-manufacturing network. During such reviews, corporate or divisional senior management can assess progress by comparing it to overall operational, financial, and strategic measures; discuss recent events, trends, and patterns; reassess risks and responses; and redirect line management as appropriate.

Management could also initiate formal quality system audits, comprehensive financial and operational audits, or other separate evaluations. Finally, it may require co-manufacturing partners to provide audited financial statements or a report based on the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board® (IAASB®) International Standard on Assurance Engagements™ (ISAE™) 3402, “Assurance Reports on Controls at a Service Organization,” as appropriate. In a U.S. context, it would be Statement on Standards for Attestation Engagements (SSAE) No. 16, “Reporting on Controls at a Service Organization.”

CALL TO ACTION

You don’t have to wait until your organization finally and formally starts “doing risk management.” Most RM/IC concepts are fairly straightforward and can easily be leveraged to enhance your existing managerial processes without the need to replace or increase them. Guidelines such as the COSO ERM Framework or the ISO 31000 Risk Management standard can help you design an appropriate approach. And if your approach increases your chances for success, it will be the best incentive for the rest of your organization to bring RM/IC to a higher level!SIDEBAR: An ISO 31000 Perspective on the Case Study

The company in the case study used the COSO ERM Framework, but it also could have used the ISO 31000 Risk Management standard, which is fairly complementary and would broadly lead to similar outcomes, although it does offer some different perspectives.

Wider Applicability

ISO 31000 can be used by any public, private, or community enterprise; association; group; or individual, and it isn’t specific to any industry or sector. The standard can also be applied to a wide range of activities and isn’t tied specifically to organizational levels or units. In addition, ISO 31000 applies to any type of objective (such as health and safety, legal and regulatory compliance, environmental protection, product quality, and more) and isn’t limited to only strategic, operational, reporting, or compliance objectives.

Prerequisites for Effective Risk Management

Before ISO 31000 discusses the actual risk management process (comparable to the components in COSO ERM), it sets out a series of leading principles and an overarching framework. The principles describe the desired outcomes of effective risk management, for example, that it should create and protect value and be an integral part of all organizational processes, specifically those involving decision making. The framework provides the foundations and a series of arrangements that cradle the actual risk management processes, such as mandate and commitment from senior management; establishment of a risk management policy, roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities; allocation of resources; integration of risk management into the organizational processes; and monitoring, review, and continual improvement.

Information and Consultation In ISO 31000, the actual risk management process starts with obtaining good information from and communicating with external and internal stakeholders, indicating their importance to all stages of the process.

Establishing the Context

The next step is establishing the internal and external context in which an organization articulates and seeks to achieve its objectives, defines the risk parameters, and sets the scope and limits for risk taking for the remainder of the process.

Objective Setting

ISO 31000 would argue that strategic objective setting is the activity that involves the most risk because a wrong decision can have disastrous consequences (and right decisions can have handsome payoffs). For that reason, the risk management process shouldn’t start only after objectives have been established but, instead, already be an integral part of the decision-making process to establish those objectives.

Risk Assessment

The ISO risk assessment process consists of the steps of risk identification, risk analysis, and risk evaluation:

- The aim of risk identification is to identify sources of risk, events (including changes in circumstances), and areas of impact that might affect the achievement of objectives.

- Risk analysis involves consideration of the causes and sources of risk, their positive and negative consequences, and the likelihood that those consequences will occur. After all, you don’t always break an arm or a leg if you trip over something.

- Risk evaluation involves comparing the level of risk found during the analysis process with limits for risk taking established when the context was considered. Based on this comparison, you can consider whether you need risk treatment or risk response.

Risk Treatment

Important considerations for selecting the appropriate risk treatment or response include:

- The characteristics (causes, consequences, and their likelihoods) of the corresponding risks;

- The organization’s limits for risk taking;

- The availability or suitability of the mix of controls, taking into account the organization’s size, structure, and culture;

- The costs compared with the benefits of more or different controls;

- The continuous contextual changes that can make existing controls ineffective or obsolete; and

- The need to remain agile, avoid overcontrol, and not become overly bureaucratic.

- Avoid a certain risk by terminating or not starting the activity that gives rise to the risk;

- Take on additional risk in pursuit of higher reward by engaging in riskier activities or lowering the level of internal control;

- Control a risk by removing the source, changing the likelihood, or changing the nature, magnitude, or duration of the consequences;

- Share a risk by insuring against the risk; or

- Accept a risk by doing nothing apart from monitoring the changes in risk.

Monitoring and Review

The organization’s monitoring and review processes should encompass all aspects of the risk management process, not only to ensure that controls are effective in both design and operation but also to:

- Obtain further information to improve risk assessment;

- Analyze and learn lessons from events (including near-misses), changes, trends, successes, and failures;

- Detect changes in the external and internal context, which can require revision of risk treatments and priorities; and

- Identify emerging risk.

SIDEBAR: RM/IC FRAMEWORKS AND GUIDANCE

If you want to establish more effective RM/IC in your organization, you can use several new or newly revised standards, guidelines, and resources. Here are three:- Internal Control—Integrated Framework and companion documents (Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), 2013) support organizations in designing and implementing internal control in light of the many changes in today’s business and operating environments.

- Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework (COSO, 2004) expands on internal control and provides key principles and concepts on the broader subject of enterprise risk management (ERM). COSO recently announced that it has initiated a project to revise its ERM Framework, with a new version to be released in 2016.

- Standard 31000:2009—Risk Management (International Organization for Standardization (ISO), 2009) sets out principles, a framework, and a process for managing risk that apply to any type of organization in the public or private sector.

For a more in-depth overview of these standards, see the article “Leveraging Effective Risk Management and Internal Control,” published in the April 2014 issue of Strategic Finance.

In addition to COSO and ISO, many other organizations, including IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) and the International Federation of Accountants® (IFAC®), provide guidance on evaluating and improving RM/IC arrangements.

April 2015