The problem with putting a human face, sometimes torso and limbs as well, on an AI machine isn’t that it will eventually diminish the importance of the human in the interactions; it’s that by humanizing the computer we’ll limit the abilities and continued development of the AI systems involved.

Anthropomorphic robots represent one more path in the long history of human-computer interface (HCI). From the earliest light pens scribbling on cathode-ray tubes, and then keyboards, a technology now 150 years old, we’ve progressed in many new directions, adding touch, voice, and eye movements, toward what some see as the ultimate goal of a silent brain-computer interface. The robotic path, however, with its promise of computerized teammates, or companions, might be a detour to dead ends because of a number of inherent problems the humanized bots bring with them.

[caption id="attachment_29477" align="alignnone" width="655"]

Shneiderman, a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland, explains the premise that encouraged the early development of robotic teammates: “A common theme in designs for robots and advanced technologies is that human-human interaction is a good model for human-robot interaction, and that the emotional attachment to embodied robots is an asset.”

[caption id="attachment_29479" align="alignnone" width="655"]

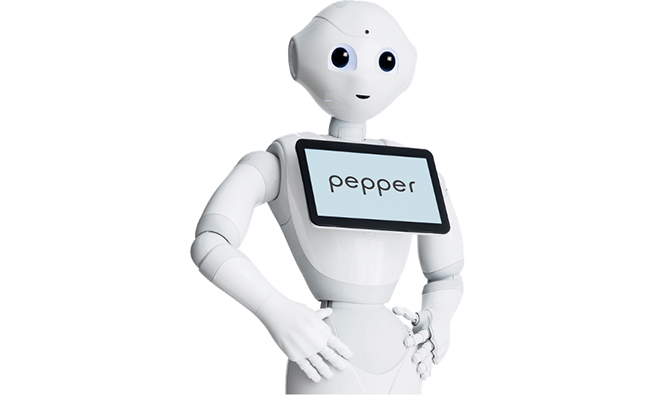

A SEMI-HUMANOID EXAMPLE

The novelty and willingness of people to respond to the four-foot tall, 62-pound robot Pepper from SoftBank Robotics won the robot employment as a receptionist at offices in Japan and the United Kingdom at banks, medical facilities, and supermarkets. And he was welcomed into homes and school labs.

Pepper was introduced in 2014, and by 2015 he was being sold publicly. Then, on June 28, 2021, SoftBank halted production. Some of the reasons for the discontinuation showed up in headlines. One described a frustrating customer experience in Tokyo: “Man arrested for assaulting Pepper, the robot that can read your emotions.” In 2018, a supermarket in Scotland fired its service robot because normal levels of background noise in the store made it difficult for Pepper to hear questions properly. That headline read, “Robot fired from grocery store for utter incompetence.” Fixing Pepper’s problems would shift attention and development even further away from what he was, an AI-powered agent, to his HCI functions.

Shneiderman cites Margaret Boden, a research professor of cognitive science at the University of Sussex, about this kind of design development detour: “Computers have distinctive capabilities of sophisticated algorithms, huge databases, superhuman sensors, information-abundant displays, and powerful effectors. To buy into the metaphor of ‘teammate’ seems to encourage designers to emulate human abilities rather than take advantage of the distinctive capabilities of computers.”

Lionel Robert, an associate professor of information at the University of Michigan, warns that with human-like robots that are treated as peers, communication partners, or teammates, there often arise three serious problems:

- Mistaken usage based on emotional attachment to the systems,

- False expectations of robot responsibility, and

- Incorrect beliefs about the appropriate use of robots.

These problems are all based on the fact that Boden and others often repeat, “Robots are simply not people.”

TEAMMATES OR TELE-BOTS

Shneiderman prefers, rather than partners and collaborators, to use the term tele-bots for human-controlled intelligent devices. He offers examples of robotic devices that have a high degree of tele-operation. The da Vinci surgical robot from Intuitive Surgical is designed for cardiac and other surgeries, but the maker insists, “Robots don’t perform surgery. Your surgeon performs surgery with da Vinci by using instruments that he or she guides via a console.”

Drones can have many automatic functions—taking off, navigating, and landing—but in war zones, they’re called remotely piloted vehicles guided by trained human pilots who themselves are responsible for what the robotics do. The reason is simple. “Computers are not responsible participants, neither legally nor morally.” They’re never accountable.

Shneiderman describes another failure of AI capacity due to the design of a rescue robot. The design team “described their project to interpret the robot’s video images through natural language text messages to the operators. The messages described what the robot was ‘seeing’ when a video or photo could deliver much more detailed information rapidly.” He asks, “Why settle for a human-like designs when designs that make full use of distinctive computer capabilities would be more effective?”

[caption id="attachment_29480" align="alignnone" width="655"]

As a contrast, Shneiderman describes how Bloomberg Terminals can partner with investing agents without losing any of the full power of intelligence due to an interface filtering.

Bloomberg Terminals are a different model of teammates that provide information from huge databases and superhuman sensors displayed on dual-screen information-abundant displays. A similar situation applies to the three-dimensional medical echocardiograms displayed in coded colors on large screens. These are teammates but ones in which no compromises are made to “humanize” the delivery of the complex information.

There’s an irony in the design of other advanced tech tools such as microscopes, telescopes, bulldozers, ships, and planes that empower people to be more effective by augmenting senses and powers to superhuman levels. “Empowering people is what digital technologies have also done, through cameras, Google Maps, web search, and other widely used applications,” Shneiderman explains. And we don’t call these tools, machines, or applications partners, nor do we think of them as teammates. If we considered them peers, we wouldn’t need them.

Certainly, there are appropriate roles for socialized autonomous companions or helpers. But the warnings from information scientists and researchers about settling on humanized androids as some kind of universal interface for AI deserve consideration.