What’s driving this growth in developed countries is the lack of workforce and the frustration with traditional farming methods trying to keep up with current market needs. The response has included more robotics with advanced sensing devices in the fields along with the invention of new agricultural tools and machines.

SMARTER INSECT CONTROL

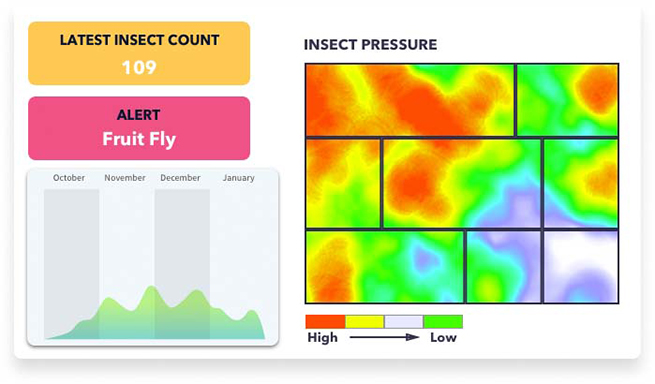

On August 19, 2020, an AgTech startup FarmSense announced a new pest monitoring system that’s able to process real-time insect classification and counting. Co-founder Eamonn Keogh explained, “The machine-learning community examines data in so many other areas, like healthcare and credit scoring, but surprisingly, no one was tackling entomology. This technology virtually eliminates the need for sticky traps and manual insect counts.” The FarmSense monitoring system (see above) can also provide an environmental benefit by decreasing the use of pesticides and insecticides through more intelligent applications.

Instead of sending workers out to collect and count what’s in sticky traps, the FarmSense traps use AI and analytics to collect information on the insects currently in the fields. Mark Hoddle, a field entomologist, and also a co-founder, says, “The insect analytics they provide allows me to really understand what is happening in specific areas of the orchard in near real-time. Better yet, the data are accessible via my phone and downloadable for analysis making quick decisions easy.”

Along with the on-board algorithms, the traps are equipped with Wi-Fi to send the data collected to the FarmSense cloud. The algorithms are customizable so the farmer can limit the reports of insects in a particular field or to just those needing monitoring.

Typical report from the FarmSense trap

Typical report from the FarmSense trap

The FarmSense traps are the result of an interesting collaboration of three different kinds of scientist—a computer engineer (Keogh), an entomologist (Hoddle), and a machine-learning expert, Shailendra Singh. All are at the University of California, Riverside. The system the team wanted to replace is widely used and comes with a number of problems.

Sticky traps are stiff yellow boards about half the size of a sheet of paper. You place them in the field or orchard, and 7 to 10 days later, you send workers out to collect them. The analysis involves identifying what insects are on the boards, and, after you count them, you compare that data with calculated thresholds to figure out what interventions might be needed.

Problem one involves human resource costs. Problem two: There might be as many as 50 different insects on a board, and you have to visually identify and count them. Problem three: By the time you realize you have a problem, you’re already 7 to 10 days behind, and given the exponential growth of some insects, that can be critical.

The FarmSense traps, on the other hand, are put in fields, and you don’t have to go back to them. The insects attracted to the baits or pheromones in the traps are immediately identified and counted, and you have that information sent to your phone or computer in seconds along with key information like when they arrived, what the movements are relating to weather, and, in some cases, you’re even given the sex of the individual insects if that’s important.

One of the trickier tasks was teaching the traps how to differentiate the bugs entering. Consider that there are 180,000 species of moth, 3,500 species of mosquitoes, 18,000 species of honey bees, and the incredible catalog goes on. In an interview, Keogh explained the FarmSense unique technology called FlightSensor, an optical sensor that classifies and counts each insect. The inventors limited the data points they would collect to the commercially important pests, and they tweaked their algorithms to note what time of day the insect was seen.

Keogh said, “We’ve been collecting data on insects over the last few years—tens of millions of insects. We breed insects, watch their entire life cycle at different temperatures and pressures, and basically have a model of bug behaviors and data points for millions of bugs. Our data is our best resource. It makes our classifications accurate, in most cases superhuman.… That is to say, we can classify as well or better than the farmer can.”

And there’s one other ingenious part of their FlightSensor. Inside the trap, there’s a light sensor, and when an insect flies in, its shadow is detected. “The signal then picks up the vibration of the insect’s wings and movement, all of which are optically recorded.” That information is essential because once noted, a machine learning algorithm is then asked to identify the visitor.

Keogh continues, “For example, a typical honeybee beats its wings about two hundred times per second. So if an insect flies in and it’s not doing 200 beats per second, it’s highly unlikely that it’s a honey bee.” The time of arrival is also a factor in the algorithm’s search. Bees like flying in the daytime, moths like night. And so the extensive catalog is cross-checked, and the new data is entered.

The first trap that the team put together cost around $500. That’s certainly prohibitive, especially given the probability of theft. Shailendra’s expertise in sensors and embedded systems has brought the cost down to $40 with the possibility of even further reductions down the line. The ultimate goal of the team’s FarmSense insect monitor is food security.

Here in United States, the results might involve yields and chemical producers’ profit margins, but in other parts of the world, the results could be far more dramatic. Keogh offers a specific example. “The corn earworm has moved into Africa and is causing incredible devastation on a continent that can’t easily afford it. We could change the profit margin of a big company, such as Monsanto, by a few percent, which is nice, but in Africa, we could make a difference to famine. That’s huge.”

THEY’RE HERE

Robots of various sizes and skill sets aren’t on their way to the fields, orchards, and vineyards—they’re there, both here and around the world. Here’s a small sampling of some of the more successful robotics already in use.

BoniRob/BoschA BoniRob robot is a weed-eliminating machine that can drive autonomously over fields. It doesn’t use insecticides, but it kills weeds by smashing them and driving them about three centimeters into the ground at a speed of about 1.75 weeds per second. BoniRob’s can also be multifunctional, spraying fertilizer.

RowBot/ Rowbot SystemsFor crops more densely planted, the RowBot can drive between rows of corn and deliver nitrogen fertilizer at the base of each plant. Robots can also do thinning and pruning.

(Left) The Sweeper Picking Robot/ Sweeper Project; (Right) Vertical Indoor Farming/ AeroFarmsThe Sweeper Picking Robot can efficiently pick soft crops like sweet peppers, and something called the Wall-Ye robot is a picking and pruning bot, which is working in vineyards in the Burgundy region in France.

The Lettuce Bot first trial run/ Blue River

The Lettuce Bot first trial run/ Blue River

The LettuceBot thinning robot has a database of more than a million images. As it drives over the rows it looks for weeds and lettuce plants that are crowding others. To these it delivers a directed shot of concentrated fertilizer that kills the weeds and unnecessary lettuce while fertilizing the other lettuce plants.

PrecisionHawk Agricultural Drone/ PrecisionHawk

PrecisionHawk Agricultural Drone/ PrecisionHawk

Drones like the selection offered by PrecisionHawk can be customized for a variety of agricultural needs, and sheep farmers in New Zealand and Ireland have been using drones to help shepherd their sheep in difficult terrain. Drones are also used in indoor vertical farming where climbing the plant racks just isn’t practical.

These are just a handful of examples of very smart AgTech robots. The catalog is large and growing rapidly. And you can now add the FarmSense bug trap to the catalog in January 2021. That’s when it will be available for sale to all.