Already much farther down the path, the EU drafted the Artificial Intelligence Act on April 21, 2021, and on September 28, 2022, released the AI Liability Directive to add teeth to the extra checks required by the Artificial Intelligence Act.

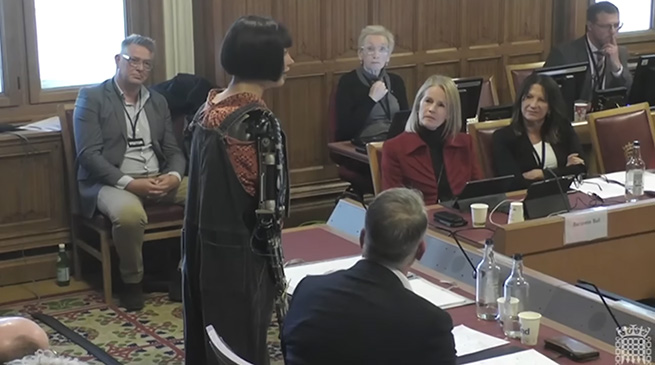

Before we take a closer look at the EU legal developments, there was a House of Lords inquiry titled “A Creative Future” in the second week of October that was investigating the possible negative impact of AI on the creative arts. One of the witnesses at the hearing was the world’s first robot artist Ai-Da, who has had international exhibitions of her paintings, sketches, and sculptures. Named for Ada Lovelace, the first computer programmer, Ai-Da does not create digital images on screens; she paints and draws with brushes and charcoal. She is able to talk using a special AI language model, but she isn’t a polemicist. She’s an artist that has been described as falling within the Dadaist school.

Her essential message for the assembled was, “I believe that machine creativity presents a great opportunity for us to explore new ideas and ways of thinking. However, there are also risks associated with this technology which we need to consider carefully. We need to think of benefits and limitations and consider ethical implications.” Alex Hern from The Guardian panned the appearance as a clumsily performed stunt, but in fairness, although Ai-Da appeared as an “expert witness,” her expertise and potential “benefits and limitations” weren’t explored. A presentation consisting of Ai-Da standing alongside one of her paintings answering direct questions about how she does what she does would have been much more relevant and revealing.

Ai-Da’s creator, Aiden Meller, and the company that built her, Engineered Arts, will likely return to booking art shows rather than political symposiums for their robot artist in the near future. But stepping back from the harsh criticisms of those who might have preferred a visit from IBM’s Watson, Ai-Da is something of a 21st Century canary in the coal mine, who instead of singing, paints. At a different venue, when she was asked by a reporter whether her work can be truly considered art, she replied, “I am an artist if art means communicating something about who we are and whether we like where we are going. To be an artist is to illustrate the world around you.” But as a robot, can she copyright a design she creates? Or if one of her sketches is taken as defamatory, could someone sue her? What’s the recourse if she uses copyrighted graphics in a work she or her agent is trying to sell? Could someone reproduce one of her paintings and sell copies without her permission? Those are the questions that would have been of useful interest at the hearing.

Elsewhere in Europe, at the EU’s Brussels headquarters, there’s a serious effort under way to address the threat AI poses not only in the arts, but also in the wide variety of human endeavors where AI, machine learning, and natural language processing have intruded.

Oversight & Accountability

“AI applications are increasingly used to make important decisions about humans’ lives with little to no oversight or accountability.” That’s how Melissa Heikkilä begins her MIT Technology Review post titled a “Quick Guide to the most important AI law you’ve never hear of.” Heikkilä is POLITICO Europe’s AI correspondent writing a weekly newsletter, “AI: Decoded,” covering how global thinking on AI is shaping the world. In the Guide blog, she offers three examples of devastating consequences of misguided AI: wrongful arrests, incorrect grades for students, and financial ruin involving a childcare benefits scandal and the Dutch tax authorities. She calls the European Union Artificial Intelligence Act the mother of all AI laws, “the first law that aims to curb these harms by regulating the whole sector.” “If the law succeeds,” she concludes, “it could set a new global standard for AI oversight around the world.”

Among the things the Artificial Intelligence Act would require are “extra checks for high-risk uses of AI that have the most potential to harm people.” These include systems used for grading exams, recruiting employees, helping judges make decisions about law, and unacceptable uses that score people on the basis of their perceived trustworthiness. The act also restricts the use of facial recognition by law enforcement and “requires people to be notified when they encounter deepfakes, biometric recognition systems, or AI applications that claim to be able to read their emotions.” And the act has opened a debate over whether lawmakers should set up a way for people to complain and seek redress when they have encountered harm from an AI system.

The EU has countered the argument that the Artificial Intelligence Act will stifle innovation by explaining that the act will only apply to the most risky AI uses, which the EU’s executive arm says would apply to only 5% to 15% of all AI applications.

Like the EU’s rigorous General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that precedes it, the Artificial Intelligence Act has serious fines for violations. Noncompliance by organizations can cost up to €30 million or, for companies, up to 6% of total worldwide annual income. Heikkilä cites some of the fines handed out by the EU for past GDPR breaches as examples of how serious the EU is about compliance. Amazon was fined €746 million in 2021, and Google was fined €4.3 billion in 2018 for breaching the bloc’s antitrust laws.

Heikkilä concludes her review of the Artificial Intelligence Act describing it as “hugely ambitious” and, therefore, “it will be at least another year before a final text is set in stone, and a couple more years before businesses will have to comply.” The project will be complex, and it likely will follow the path taken by the GDPR, which took six years to go from draft to set law.

Liability Directive

A second bill published by the EU on September 28, 2022, is a proposal for adapting noncontractual civil liability rules to AI. The shortened name for this sister legislation is the AI Liability Directive. What it does, in a nutshell, is give people and companies the right to sue for damages when AI causes harm. In the more formalized language of the directive, the need for it is found in the nature of AI procedures:

“Current national liability rules, in particular based on fault, are not suited to handling liability claims for damage caused by AI-enabled products and services. Under such rules, victims need to prove a wrongful action or omission by a person who caused the damage. The specific characteristics of AI, including complexity, autonomy, and opacity (the so-called “black box” effect), may make it difficult or prohibitively expensive for victims to identify the liable person and prove the requirements for a successful liability claim. Victims may therefore be deterred from claiming compensation altogether.”

Heikkilä explains that the directive will hold developers, producers, and users of AI technologies accountable not only for damages caused, but also for providing access to information about the system so plaintiffs can name those responsible and discover what went wrong with the AI system involved.

Catching Up

The AIRankings group lists the U.S. as number one in the world for AI research based on adjusted publications. They rank the top five as: 1. U.S., 2. China, 3. UK, 4. Germany, and 5. Canada. The research categories include AI in general, computer vision, natural language, machine learning, cognitive reasoning, robotics, multi-agent systems, and simulation. Missing on that list are the ethical concerns and legislation to address both oversight and accountability. And missing in the congressional hearings room is any proposed legislation to address the problems AI has the potential to create in the world of the arts and copyright law, and for recruiting agencies, loan approval departments, police departments considering predictive enforcement algorithms, and more that we already know of and those which we don’t. Ai-Da is already hanging her warnings on gallery and museum walls around the world.