The papers were prepared by Stephen L. Thaler, an AI researcher, and his Missouri-based company Imagination Engines. The application data sheet listed a single inventor “with the given name DABUS and the family name Invention generated by artificial intelligence.” An additional clarifying statement was provided to USPTO that explained, “DABUS, the inventor, was executed by Stephen L. Thaler, who [is] both the legal representative of DABUS and the Applicant.” As expected, the application was rejected by the patent office because DABUS wasn’t a human.

This wasn’t the only failure of the AI inventor appearing before government patent agencies. DABUS has been rejected as an inventor in Europe and the U.K. for the same reason—it lacks “personhood.” Yet Imagination Engines persists in calling DABUS a “true artificial inventor” that has been created to mirror the same patterns of thought that go into human inventions. And as simple and straightforward as the legal requirements for patents seem, the numerous DABUS applications have, in the minds of some AI researchers, opened a large can of worms.

THE LAW

Patent laws are designed to be practical, but they can be arbitrary or confusing. Corporations lack personhood, but they can own, sell, or buy patents. They just can’t be inventors in the legal papers. Inventors are allowed to use tools to create their inventions, but now there’s a growing controversy over computer systems used as tools, which can learn and actually create their own programs or develop skills to best humans in games from Checkers to Go. When machines like DABUS can come up with solutions before any human has imagined or created the same, how is that different? And finally, should a machine be allowed, or are they even capable, of owning and managing the rights for their own invented works? It seems nonhuman corporations do.

The worms have been released, and now these and other problems need to be addressed. Here are a few observations from commentators and then a brief look at how DABUS comes up with its unique solutions/inventions.

AI MACHINES

When Thaler’s application was rejected out of hand by the U.K. Patents Office in August 2019, the Financial Times offered a few thoughts on “necessity as the mother of invention” and how “it may well be a necessity that the law change to accommodate machine-designed inventions.”

The paper pointed out that the container and the flashlight designed by DABUS match all the primary requirements to receive a patent, and the office admits that. What’s different then is the reluctance to grant “this first recorded instance of a non-human to ever be credited as an inventor of a product.” The official argument offered by the patent office was, “There could be legal complications, they claim, if corporate inventorship were recognized.”

DABUS’s container idea is an ingenious adjustment using fractal designs that creates pits and bulges in the sides of the container to adapt to the limitations of autonomous gripping hands. The Times sums up the problem this way: “Prototypes of containers such as these could well be created by robots; they would be used by robots too, and now academics are suggesting that humans should have no credit in the invention.”

But the UK’s Patents Act of 1977 insists that any inventor must be human. According to a point presented by Thaler in the patent application, “It has been argued that a natural person may claim inventorship of an autonomous machine invention even in situations in which that person was not involved in the development or operation of a machine by virtue of recognising the relevance of the machine’s output.”

The Times concludes, “It may well be a necessity that the law change.”

In an August 2019 artificialinventor.com article, “Should an AI system be credited as an inventor,” Robert Jehan argued similar points for the Imagination Machines company. He explained the source of the decades-old patent laws decision that deem computer programs to be “non-inventions” and not patentable as such. And because they more resemble literary works, they should be protected by copyright law.

Today, however, computer programs can be designed to be unsupervised self-learners. Jehan says, “This raises the question whether an AI system could develop new technology that an associated person (such as the creator of the system, the original programmer, the user of the machine, and so on) cannot reasonably say he or she truly contributed to in terms of having taken part in inventing. This premise is not science fiction or even merely possible but is probable if not inevitable.” Some have predicted the arrival of Machine General Intelligence (human-equivalent intelligence) in 2040. At that point, older legal definitions for “inventor” will no longer apply.

Another important consideration regarding AI inventors involves the ethical responsibilities of the inventor for whatever he, she, or it creates. This is a current problem still awaiting some generalized regulations acceptable to all. You would assume there’s general agreement that machines shouldn’t be given freedom to investigate any possible inventions.

HOW DABUS “IMAGINES”

To get a quick (oversimplified) idea of how DABUS generates original concepts, here’s Thaler’s explanation of what DABUS is and what it does. (The name DABUS stands for a Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience.)

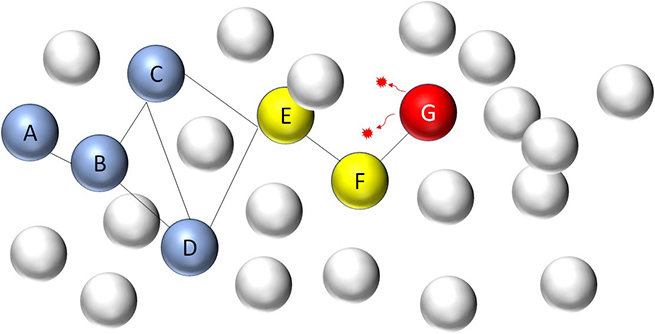

It “starts as a swarm of many disconnected neural nets, each containing interrelated memories, perhaps of a linguistic, visual, or auditory nature. These nets are constantly combining and detaching due to carefully controlled chaos introduced within and between them.” This is what a swarm looks like.

Image courtesy: Imagination Engines Inc.

Image courtesy: Imagination Engines Inc.

“Then, through cumulative cycles of learning and unlearning, a fraction of these nets interconnect into structures representing complex concepts. In turn, these concept chains tend to connect with other chains representing the anticipated consequences of any given concept. Thereafter, such ephemeral structures fade, as others take their place, in a manner reminiscent of what we humans consider stream of consciousness.”

In DABUS, ideas aren’t represented as “on-off” patterns of neuron activations. The structures get created, connect, call on other nets for other information, fade, and are replaced by others until desirable outcomes appear and get reinforced. These outcomes (ideas) get converted into long-term memories that can be called on for further information or part of a new imagining.

Thaler explains, “DABUS [can be] interrogated for its cumulative inventions and discoveries.” Further, many ideas can form in parallel across multiple computers. To control this part of the process, detection and isolation of freshly forming ideas is possible through adaptive neural nets known as “novelty filters” that don’t supply feedback that might influence the generating nets. Imagination Engines provides a complete explanation (bit.ly/2AkvrRr).

Two things appear certain at this point. IMI intends to request credit where they think it’s due in future DABUS patent applications, and there’s yet sufficient interest on the part of patent agencies to reconsider archaic assumptions about computing in their legal formulas. Perhaps it will take one very dramatic patent proposal that captures the public imagination or a lawsuit involving an autonomous vehicle and a human-driven automobile to initiate a serious review of existing law.