This article is based on research funded by a grant from the IMA® Research Foundation.

As society demands a shift from a narrow view of accountability that serves only shareholders toward an ethical view, there’s an increasing drive for companies to disclose more information on carbon emissions; diversity; environmental, social, and governance (ESG); and other sustainability metrics. In fact, the rates of sustainability reporting among the world’s leading 250 companies are at 96%, up from just 12% in 1993, and three-quarters of these companies connect their activities to the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indeed, ESG disclosures are cited by The Wall Street Journal as among the top 10 challenges faced by finance chiefs, while the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) have been intensively working on sustainability reporting standards and the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) has proposed rule changes on climate-related disclosures (see “Reporting Standards”).

Reporting Standards

ISSB: The ISSB has issued global sustainability disclosure standards that provide a global baseline for companies to report on their sustainability-related risks and opportunities, with specific reference to climate-related disclosures.

EFRAG: In April 2021, the European Commission adopted a legislative proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) that requires companies within its scope to report using a double materiality perspective in compliance with European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) adopted by the European Commission as delegated acts. The first companies will have to apply the standards in the financial year 2024 for reports published in 2025.

SEC: The SEC has proposed rule changes that would require registrants to include certain climate-related disclosures in their registration statements and periodic reports. This includes information about climate-related risks that are likely to have a material impact on the business, results of operations, and certain climate-related financial statement metrics in a note to companies’ audited financial statements.

|

A “digital stakeholder” is one that has been empowered by current digital tools to access myriad sources of information about corporations. By leveraging corporate websites, social media platforms, and stakeholder engagement platforms that allow for two-way communication, stakeholders can access up-to-date, comprehensive information about companies in a timely and efficient manner. Digital technologies allow stakeholders to collect information on what’s important to them and to more easily interact to pressure organizations into making novel disclosures. This makes the multidimensional nature of value—the idea that the value of a corporation is not solely determined by its financial performance, but also by a variety of other factors that matter to a broader range of stakeholders (rather than solely to shareholders)—more explicit than ever before. These factors can include a company’s social and environmental impact, its reputation and brand value, and its relational capital. This concept recognizes that corporations create (or destroy) value in many ways that aren’t captured by traditional financial metrics and is part of a broader shift toward more holistic and sustainable ways of measuring corporate performance to embrace the expectations of different stakeholders.

This drive for greater disclosure brings with it major challenges as businesses navigate the changing world of ESG and sustainability reporting. For instance, what are the complications underlying the definition of sustainable key performance indicators (KPIs) given the new, multidimensional, and more volatile notions of value expressed by stakeholders? What is the role of new technologies in supporting a more dynamic approach to how corporations communicate information regarding workers and human capital, customer relationships, governance, trust, transparency, and sustainable projects? And what is the role of a company’s finance function in this evolution?

Our Study

We conducted a research study in which we interviewed senior managers at two companies, Novo Nordisk and CARE (a pseudonym used for confidentiality), in order to understand how companies are navigating the dynamic world of sustainability. We chose these two businesses because both have been involved in ESG for nearly two decades and have developed best practices in sustainability. There are no clear-cut definitions, standards, and responsibilities in the ESG space, so trying to be a leader in this regard is a challenging and ever-changing endeavor. We used these two case studies to show the sustainability reporting landscape and how it may evolve as a result of the pervasive use of digital technologies.

Novo Nordisk is a leading global pharmaceutical company that treats diabetes, obesity, and other serious chronic diseases, and it defines sustainability in terms of adding value to society and its future business. The company measures value in relation to patients (e.g., number of patients reached with diabetes-care products; patients reached via access and affordability initiatives; and healthcare professionals trained), employees (e.g., number of total employees; employee turnover; and gender in leadership, management, and its board), suppliers (e.g., number of direct suppliers), the government (e.g., the company’s total tax contribution), and shareholders (e.g., dividends and share repurchases).

The company follows the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the UN Global Compact, the UN’s SDG Leave No One Behind principle, and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) reporting principles.

Key Terms

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights are a set of guidelines for states and companies to prevent, address, and remedy human rights abuses.

The UN Global Compact is a voluntary initiative based on CEO commitments to implement universal sustainability principles in support of UN goals.

The UN SDG Leave No One Behind principle is the central promise of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its SDGs. It represents the unequivocal commitment of all UN member states to eradicate poverty in all its forms, end discrimination and exclusion, and reduce the inequalities and vulnerabilities that leave people behind and undermine the potential of individuals and of humanity as a whole.

The IIRC set out a principle-based framework called the Integrated Reporting <IR> Framework. An integrated report combines both financial and nonfinancial information and communicates how an organization’s strategy, governance, performance, and prospects, in the context of its external environment, create, preserve, or erode value in the short, medium, and long term.

The UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. It was adopted by all UN member states in 2015. At its heart are the 17 SDGs, which recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand in hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth—all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests.

The TCFD has developed a framework to help public companies and other organizations disclose climate-related risks and opportunities.

The SASB is a nonprofit organization that has developed industry-specific sustainability accounting standards. These standards identify the subset of sustainability issues most relevant to financial performance in each of 77 industries. As of August 2022, the ISSB of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation assumed responsibility for the SASB Standards.

CDP is a not-for-profit charity that provides a system for measuring, detecting, managing, and globally sharing information regarding climate change.

GRI is a nonprofit international organization established to define the standards of sustainable performance reporting for companies and organizations of any size, belonging to any sector and country in the world.

|

Novo Nordisk has conducted a materiality assessment of all 169 targets toward the materiality of its operations and license to operate using the SDG Self-Assessment Tool, which was developed by the Earth Security Group together with SAB Miller. This helps the company formulate ways of maximizing its positive impact and minimizing its negative impact, while also actively working on partnerships that allow it to address specific UN SDGs. For example, through its Cities Changing Diabetes partnership program, Novo Nordisk addresses SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

The second company, CARE, operates around the globe and sells its products worldwide. Its products range from personal to home care. It practices innovation across the value chain via brand building, supply chain management, and the use of digitization and data analytics. In particular, it focuses on lean innovation, combining consumer-based insights with breakthrough science.

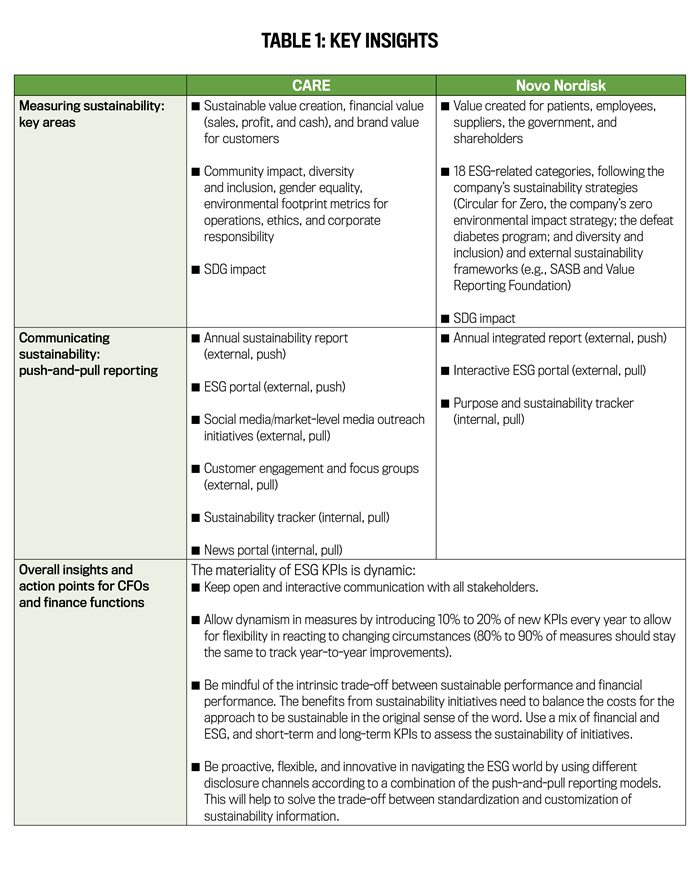

CARE considers corporate citizenship an important facet of its business, which revolves around five key areas: community impact, diversity and inclusion, gender equality, environmental sustainability, and ethics and corporate responsibility. For instance, it works on a number of global programs as well as specific regional campaigns in various countries. Equality and inclusion start inside the company and reach outside the corporate boundaries to partners from the supply and value ecosystem and local communities. In this vein, CARE has developed a plan with 14 goals and actionable steps that impact employees, brands, partners, and citizens. The company also created a set of goals in line with the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, targeting not only the reduction of its environmental footprint, but also the ways it can help restore the world, for example, through the reuse of packaging, helping to save energy in homes, and reducing the environmental footprint of suppliers, buyers, and manufacturing sites. (See Table 1 for a summary of key insights from the two case studies.)

Measuring Sustainability: Key Challenges

Developing concrete measures for sustainability takes time and persistence and isn’t necessarily uniform across the various aspects of sustainability. Sustainability measurement is a process that involves trial and error, especially given the presence of different external sustainability frameworks and constant pressures for more disclosure from stakeholders, including regulators and investors. For example, up until 2021, Novo Nordisk had to respond to multiple questionnaires coming from investors, rating agencies, and regulators. Some of these questionnaires overlapped in terms of requested ESG information, which led the company to find a creative and cost-effective solution to streamline its response to ESG queries through a virtual ESG portal, combining static and dynamic ways to present information.

Both companies would benefit from current trends toward standardization of sustainability metrics because this would reduce some of the pressures both face in navigating the demanding and changing ESG space. However, one of the greatest challenges is that it’s difficult to predict which KPIs will matter in a few months, or even in a year, as circumstances change. The materiality of sustainability KPIs is dynamic. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t figure into the predictions of multinationals, yet it has propelled them to reflect on what to do differently in the future, including investing more in sustainability initiatives for employees, customers, and supply chains. This has translated into changes in sustainability KPIs.

Managers at CARE noted that consumers in certain countries have become far more aware of sustainability issues since the start of the pandemic. In addition, managing supply chains, especially during COVID, meant focusing on bringing products directly to customers as well as on expanding the use of data platforms and machine learning to assess consumer consumption and raw material availability. CARE adheres to two principles when determining KPIs: stability and dynamism. Stability means that at least 80% of measures are the same year over year to allow CARE to track improvements. Dynamism translates into introducing 10% to 20% of measures every year to allow for flexibility to reacting to changing circumstances. Thus, the expectations of digital stakeholders are dynamic and continuously evolving.

Another complex aspect is to reconcile sustainability/ESG performance with financial performance. Not all sustainability initiatives are straightforward in terms of value creation and consequences; some may take time to achieve financial stability. For instance, one element that complicates sustainability performance is the life-cycle assessments of products and striking a balance between different dimensions of sustainability. For example, CARE has made a clear commitment to uphold sustainability across all its brands and products but not at any cost, so the trade-off between sustainability and cost is addressed on a case-by-case basis. Another good example is the conundrum of using plastic rather than glass packaging in products. From the standpoint of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, the energy impact of recycling glass is worse than that of plastic. Plastic waste is more abundant than glass waste, however, and plastic is a more visible issue to tackle from the standpoint of consumers.

In some cases, there’s an intrinsic trade-off between sustainable performance and financial performance. For example, when determining what ESG initiatives to implement, companies need to determine what structural changes can be made (e.g., switching to electric vehicles or changing product packaging) and what measures to compensate with (e.g., planting trees). CARE, for example, prefers to follow strategies resulting in a combination of structural solutions and compensatory effects, although its managers observed that numerous companies prefer compensating initiatives because they’re easier to implement and track and, sometimes, they’re less costly. CARE is also aware that not all sustainability KPIs can be clearly formulated and translated into monetary terms. Environmental KPIs may lend themselves more easily to such translations, while social KPIs, which are inherently more complicated to track and more connected with sentiment, may present a certain level of difficulty in being monetized. In any case, both companies recognize that the benefits from sustainability initiatives need to balance the costs to be sustainable in the original sense of the word.

Communicating Sustainability

Both Novo Nordisk and CARE have various layers of ESG disclosures resulting from regulatory requirements as well as voluntary choices. Novo Nordisk produces an audited annual integrated report containing a dedicated ESG section. This formalized communication covers financial, environmental, and social statements, as well as a management review. It’s a single inclusive document offering a comprehensive overview of the company’s performance, progress, positions, and strategic initiatives.

The ESG portal, which is available on Novo Nordisk’s website, allows the company to pool relevant ESG information into one platform. Novo Nordisk introduced the ESG portal in an attempt to present ESG information in one place in both static (through webpages and Excel spreadsheets) and dynamic (through Tableau-powered visuals) ways not only to satisfy the overlapping requests of investors and rating agencies, but also to allow all stakeholders to interact with ESG information in their own way. This portal allows interested parties to interact with different ESG-related data (i.e., energy consumption, water consumption, CO2 emissions, waste, patients reached with diabetes care products, donations and other contributions, employees, health and safety, animals purchased for research, diversity and inclusion, human rights and labor rights, business ethics, facilitations, supplier audits, patient safety and product quality, company trust, sustainable tax approach, and environmental management). The ESG portal could, for example, help active investors find answers to the more specific questions they prefer to ask, such as how the company addresses human rights violations in its supply chain. Passive investors, who are more interested in asking the same questions of all the companies in their portfolios, would also be able to find the more general ESG information they need. Other stakeholders, such as consumers or society at large, may locate information on how, for instance, the company has worked toward gender equality and diversity.

Novo Nordisk also has an internal channel, the Purpose and Sustainability Tracker, which provides quarterly updates to all internal stakeholders (e.g., employees, its locations in different countries, and production sites) and allows them to gauge the company’s performance against its corresponding peers in terms of ESG metrics.

In line with its social responsibility and corporate citizenship drive, CARE produces an annual sustainability report. The company replicates this report on the website of each location in other countries to underline its impact across regions.

For the purpose of investors, CARE also maintains a dedicated ESG portal that covers information contained in the sustainability report. However, it presents this material in a manner tailored to the information needs of investors, with separate sections for ESG matters as well as for the various reporting frameworks CARE adheres to, including the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), CDP, and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).

The company also encourages employees to share ESG impact stories on social media to show the value that the company and its businesses are creating. CARE allows consumers to send the company a message through its Facebook page and also to reach out to individual CARE employees through their LinkedIn profiles. The company also runs a specialized program for CARE ambassadors, offering comprehensive training to certain employees of all functions and levels on how to represent the company. Similar to Novo Nordisk, CARE also maintains a sustainability tracker, which presents up-to-date aggregated employee and brand initiative performance. With the pandemic hindering in-person communication, CARE also started a quarterly COVID-19 newsletter to address the reduced information flow to employees. This newsletter has now morphed into a news portal available on the company website.

In addition, over the past few years, CARE has been in the process of rapid automation and digitization of various processes to enhance productivity. The company also uses machine learning to establish algorithms for making decisions. Yet there are some stakeholder engagement processes, such as regular focus groups with consumers, that can’t be digitized.

Both Novo Nordisk and CARE are thus proactive in their approaches to using technology to aid their ESG disclosures. Also, both have taken on the initiative of educating their stakeholders on aspects of sustainability with which stakeholders are struggling. Novo Nordisk is communicating with its passive and active investors, which allows the company to transfer ESG know-how to investors while at the same time allowing it to learn the ESG views of its investors. CARE has education initiatives for its consumers, as it believes that better-informed consumers make better sustainability-related decisions, which ultimately impact not only CARE but also society as a whole. CARE believes in making consumers part of the ESG solution rather than part of the ESG problem.

Key Messages for CFOs and the Finance Function

The disclosure practices we observed in Novo Nordisk and CARE reflect the multidimensional value created by various initiatives that both companies promote, and the use of digital technologies allows them to engage in open communication with stakeholders. This benefits both sides in understanding each other better as well as in making the development and maintenance of dynamic KPIs possible.

Indeed, the two case studies hint at the evolving way in which information is disclosed. Beyond what’s reported, just as critical is how this information is delivered. Specifically, we’re witnessing a combination of a “push and pull” notion of value and corporate reporting. In the push model of reporting, the report producer has control of the scope, timing, and modes of delivery of disclosures. Conversely, in the pull model, the availability of new technologies and of large pools of data, which can be recombined at will by digital stakeholders, implies that their ability to invent or ask for measures of performance that are in line with their perceived notions of value is of an exponentially high quantity and variety.

For instance, although Novo Nordisk’s annual integrated report is a good example of push reporting, its ESG portal allows stakeholders to pull information in the manner they choose. Likewise, CARE’s annual sustainability report exemplifies push reporting, but stakeholders can also engage with the ESG information through several social media platforms at their own pace and in their own way, thus pulling information that’s relevant to them.

This combination of a push-and-pull model also lets possible trade-offs emerge between the different dimensions of financial value and other values. Corporate sustainability measures vary and reflect different—and sometimes conflicting—stakeholders’ expectations, so the challenge is in consistent measurement and management from company to company. Further, a balance between short- and long-term results can be elusive. The market-driven focus is on short-term results, but a full appreciation of sustainability necessitates an accounting for long-term considerations as well, such as issues of intergenerational justice, climate change, and sustainability development.

Finally, we learned from our study that companies should ensure that CFOs and finance functions focus on sustainability. As strategic partners and financial advisors, sustainability is part of the job. CFOs understand how sustainability can align positively with both the strategic goals and financial value creation of their companies in the short and long term. They’re used to using standards (for producing financial statements) and to flexibly adapting KPIs and reports to respond to the information needs of their final users (for internal performance measurement and evaluation). Therefore, CFOs know how to balance the current tensions between standardization and customization of sustainability information.

Sustainable CFOs ideally use data and new tools to support the integration of ESG into strategic decision making and investment strategies. They ensure ESG data quality for external and internal reporting and drive sustainability improvements throughout the organization, setting KPIs, tracking and monitoring progress, and integrating ESG into budget setting, forecasting, and incentive systems. By leveraging digital technologies, sustainable CFOs are in the best position to collect company-wide data and provide reports and dashboards that can be used interactively, internally and externally, according to both a push and a pull logic.

Companies today need innovative modes of reporting and of designing sustainability performance metrics based on engagement with different audiences. New technologies are pivotal to this evolution, and the role of the finance function therefore becomes even more crucial.

Further Reading from IMA

Reports

Cornelis T. van der Lugt, Shari Helaine Littan, Milana Erlik, Basheer Abhari, and Aspen (Harding) Axelman, Climate Risk and Strategies: Finance Function Readiness to Meet Accelerating Demands, December 2022.

Loreal Jiles, Shari Helaine Littan, Diane Jules, Roopa Venkatesh, Brad J. Monterio, and Heather H. Collins, Diversifying Global Accounting Talent: Actionable Solutions for Progress (with CalCPA and International Federation of Accountants), April 2022.

Shari Helaine Littan, Arnaud Brohé, Kevin Fertig, Christine Khong, and Jaxie Friedman, Management Accountants Role in Sustainable Business Strategy A Guide to Reducing a Carbon Footprint, February 2022.

Delphine Gibassier, Diane-Laure Arjaliès, and Claire Garnier, Sustainability CFO: The CFO of the Future? May 2018.

Strategic Finance articles

Anum Zahra, Brad Monterio, and Paul E. Juras, COSO and Trust in Sustainability Reporting, May 2023.

Daniel Butcher, People, Planet, and Profit at King Arthur Baking Company, March 2023.

Brigitte de Graaff and Paul E. Juras, Integrated Thinking for Sustainable Business Management, February 2023.

Amanda Pavan and Jerry G. Kreuze, The SASB and Sustainability Standards, September 2022.

Daniel Butcher, CFO to CFO: Leading the Way on Sustainability, April 2022.

Brigitte de Graaff, Sustainable Business Management, April 2022.

Mark L. Frigo and Ray Whittington, SASB Metrics, Risk, and Sustainability, April 2020.

Shari Littan, Liv Watson, and Natalia Kaleta-Schraa, Financial and Sustainable Reporting Converge, January 2021.

Cristiano Busco, Giovanni Fiori, Mark L. Frigo, and Angelo Riccaboni, Sustainable Development Goals, September 2017.

Certificate

IMA Sustainability Business Practices Certificate™

|

November 2023