The recent wave of bank failures including Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, First Republic, and Credit Suisse is a symptom of the continued use of weak first-line risk governance. Regulatory attempts to plug holes won’t prevent more risk governance disasters if regulators and the audit and risk professions refuse to address the harsh reality that the core assumptions in corporate risk governance today are fatally flawed and continue to fail key stakeholders in colossal ways.

Weak first-line risk governance is an approach where those responsible for key mission-critical objectives—like liquidity in banking, safety in companies like Boeing, compliance with the laws at Wells Fargo, or reliable financial disclosures required of all public companies—aren’t trained and required to assess and report on the status of residual risk to the CEO and the company’s board of directors. Second-line risk groups and third-line internal audit functions try to compensate for this gap by using ineffective legacy risk and internal audit methods. In some cases, CEOs even prevent boards of directors from seeing the flow of risk status information that risk groups and auditors are aware of within the company (Wells Fargo and WorldCom are two such examples). While this goes on, external auditors who are often aware of major problems, including widespread illegality and regulatory infractions, sometimes stand by and certify financial reports that present a materially misleading position to stakeholders (e.g., SVB).

Weak first-line risk governance—the dominant risk governance approach in use today— continues to fail repeatedly. Why can’t or won’t regulators, as well as risk and audit professionals, see the real root cause and address it? We suspect a mix of paradigm paralysis, herd mentality, and cognitive biases is at work.

HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF

Almost 40 years before the demise of SVB and Credit Suisse, Justice Willard Estey chaired a Canadian royal commission investigation looking into the failure of two of Canada’s eight major banks at the time. According to Alix Granger in The Canadian Encyclopedia, the August 1986 report of the commission’s findings discovered that

“…management, directors, auditors and regulators were all seriously lacking in the performance of their duties. It criticized the banks’ management for improvident lending policies and bizarre banking procedures, overstated income and loan values and misleading financial statements. The external auditors, the report stated, accepted financial statements that did not follow accepted banking practices nor reflect the true financial position of the banks. The commission claimed that the directors had relied heavily on management and had not performed their customary function of setting policy and directing management. The regulators, in turn, had made no independent assessment of the loan portfolio and did not support the auditors when they challenged management, relying instead on the banks’ own reports and on discussions with management in what the commission termed ‘a wink and nod system.’ Furthermore, it claimed that the Inspector General of Banks had full knowledge of the situation but refused to act and therefore bore much of the blame.”

Sadly, given the most recent wave of risk governance debacles highlighted by SVB, it appears little has changed. The failures of SVB and Credit Suisse show that the current paradigm of weak first-line governance needs to be replaced with strong first-line, objective-centric, demand-driven risk governance.

The challenge is how best to accomplish the goal of establishing a culture of personal responsibility and accountability where management, the first line, is willing to effectively identify and escalate concerns to the board. When a board is fully apprised of management’s risk taking linked to key objectives, then the job of risk functions and internal audit is done unless they believe the board’s decision making is so egregious that they need to take the career-risking step of blowing the whistle to regulators or law enforcement.

Once boards are apprised of the true state of risk linked to key objectives, it’s up to board members to decide whether they’re okay with management’s risk acceptance decisions or if the board needs to intervene. Overseeing management’s risk management process and risk taking in pursuit of key objectives is, or should be, seen as a core part of the board’s oversight responsibilities and purpose.

WEAK FIRST-LINE RISK GOVERNANCE

The roots of weak first-line risk governance date back to early command-and-control beliefs of how a company should be “controlled.” Driven by the views of the audit and accounting professions at the time, early “internal control” thinking focused on having companies create policies and rules, then setting them out in corporate policies. Regulators wanted to see evidence of plenty of rules spelling out what employees were expected to do as well as evidence there were people assigned to check whether the policies and rules were being followed.

This thinking guided the founding principles of The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) as well as what is considered the “internal audit Bible”: Sawyer’s Internal Auditing: Enhancing and Protecting Organizational Value, seventh edition. The book described internal audit primarily as compliance-centric—checking that rules and policies are being obeyed. Internal audit’s primary job is to ferret out management’s “internal control weaknesses and deficiencies” and report them to senior management and the board.

This concept still lives today. The modern vision of internal audit’s role since 2020 has been IIA’s Three Lines Model. Originally known as the Three Lines of Defense, the central premise in the model is that management, as the first line of defense, isn’t trained or required to formally assess and report on the state of risk linked to key organizational objectives. The job of second-line functions, including risk groups, is to monitor and report on risk-related matters. The role of internal audit, which comprises the third line, is vaguely described as providing independent and objective assurance and advice on all matters related to achieving objectives.

Most of the world’s regulatory regimes, including those in the banking and financial sector key to global financial stability, operate on the premise that management isn’t the primary risk assessor and reporter. With weak first-line risk governance, management isn’t expected to formally assess and report upward on the state of risk linked to the achievement of objectives for which it’s responsible. Neither is management expected to undergo training on how to formally assess and report on the degree of certainty that key objectives will be achieved with a level of risk acceptable to the CEO and the board. The job of formal risk assessment and reporting is left to second-line functions and third-line internal audit.

MISDIAGNOSING FAILURES

We’ve been studying regulatory response to risk governance failures for more than four decades. Tim Leech’s 2011 joint paper, “Preventing the next wave of unreliable financial reporting: Why US Congress should amend Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act” in the International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, chronicled multiple waves of risk governance failures and regulatory response dating back to the ’70s. His 2012 paper, “The High Cost of Herd Mentality” for the London School of Economics Center for Risk and Regulation, described guiding principles that regulators around the world continue to apply, regardless of their low effectiveness and success rate. Parveen Gupta’s “COSO 1992 Control Framework and Management Reporting on Internal Control: Survey and Analysis of Implementation Practices” for IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) pointed to serious problems in regulators’ and standard setters’ practices for how to best assess, and report on, the state of risk.

In virtually all the cases we have studied, the primary responsibility to assess and report to the board on the state of risk linked to key objectives wasn’t assigned to management. Risk functions and internal audit were expected to fill that role. This is counterintuitive since management, not these functions, is responsible for achieving the company’s objectives that flow from its strategic plan.

This weak first-line risk governance is the core assurance paradigm today, despite its incredibly high failure rate. Why can’t regulators around the globe see the root cause of the problem? We suspect it’s because regulators like the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) and its counterparts in countries around the globe take their advice from organizations that have built their training and certifications around the premise that auditors should be primary risk assessors and reporters, not management. We label the strong attachment to weak first-line risk governance as “paradigm paralysis” and believe it requires serious reconsideration.

The most visible manifestation of this cognitive bias was seen in 2003. The SEC had generated a discussion paper describing how it intended to implement Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). That exposure draft proposed the following wording for Section 404(b) related to management’s internal control attestations:

“With respect to the internal control assessment required by subsection (a), each registered public accounting firm that prepares or issues the audit report for the issuer shall attest to, and report on, the assessment made by the management of the issuer. The external auditor must provide an opinion on the reliability of the assessment developed by management in section 404(a)(2).”

This exposure draft called for management to prepare a risk and control assessment related to the objective of reliable financial disclosures. The external auditor was to audit that assessment and opine on it. This is one of the few instances in risk governance history we have found where a regulator called for a strong first-line risk governance model, i.e., one where the first line would be the primary assessor and reporter.

In the end, the SEC changed the wording in its final guidance so external auditors would form their own independent opinion on internal control effectiveness. This is a distinct difference from having them audit and report on the reliability of management’s assessment of internal control and the reliability of information the board is receiving about the risks being accepted linked to the objective of reliable financial statements.

In a large percentage of the major risk governance disasters, however, the boards of directors involved have asserted and continue to assert that they didn’t know. The recent Wells Fargo debacle is a classic example. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which regulates Wells Fargo, is fining the company’s chief risk officer and two chief internal audit executives tens of millions of dollars (which the individuals are appealing). The board’s role in the Wells Fargo scandal appears to have received little attention.

The lack of responsibility and accountability of management to assess and report on the residual risk status to the board is not only problematic, it’s also tantamount to breaching its fiduciary duties to the shareholders. This is the flaw that then-chairman at Credit Suisse António Horta-Osório identified when he said in 2021:

“We are committed to developing a culture of personal responsibility and accountability, where employees are, at heart, risk managers; know exactly what they must do; escalate any concerns; and are responsible for their actions. Such a culture is of critical importance and, by working relentlessly on this goal, we can create lasting change and value for both clients and shareholders.”

What’s missing in his diagnosis is the need for management to be trained, to be required to periodically identify and assess risks that threaten achievement of key objectives for which it’s responsible, and to report the results for mission-critical objectives to the boards of directors.

We believe this is the primary failing of weak first-line risk governance. The focus should be on ensuring there’s agreement about the acceptability of risk linked to mission-critical objectives, up to and including the board. This includes ensuring reliable financial statements, safety, liquidity in banks, and other mission-critical objectives specific to different sectors. To accomplish that, there must be a reliable system in place to ensure management has a robust understanding of the true state of risk and certainty that key objectives will be achieved, and that the CEO and board are receiving reliable risk and certainty status reports linked to those mission-critical objectives to support their decisions.

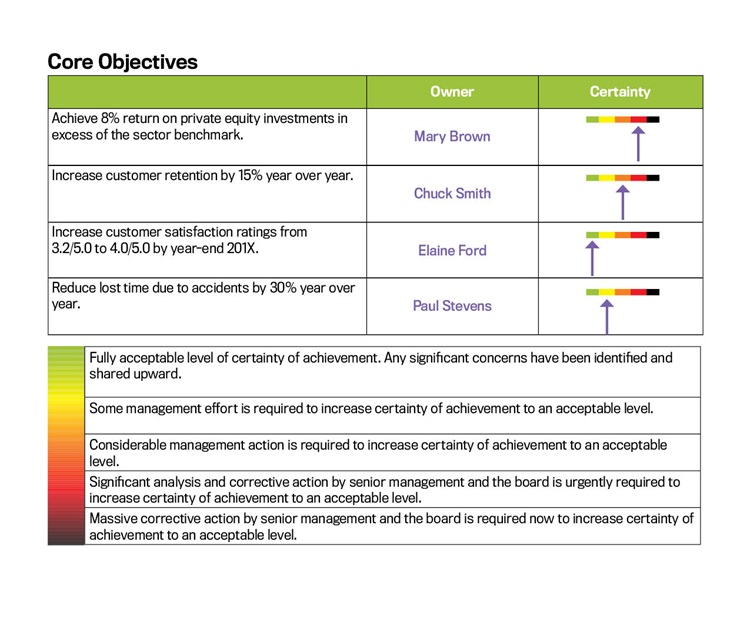

Yet the dominant approach to enterprise risk management (ERM) has been risk functions creating and maintaining lists of risks in “risk registers” that purport to be the entity’s “top risks.” Even though the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) definition of “risk” is “effect of uncertainty on objectives,” most CEOs and boards don’t receive risk assessments of the composite effect of uncertainty or risk on achievement of key objectives. Similarly, they also don’t get regular updates on the residual risk status affecting their company’s mission-critical objectives.

On the internal audit front, internal auditors develop annual audit plans and provide their view of management’s significant deficiencies and material weaknesses in order to comply with legislation like SOX and their sense of what else the CEO and board want. The methods they use usually include a mix of first-generation compliance-centric approaches dating back to the 1940s, second-generation process-centric approaches from the late 1970s and early 1980s, and third-generation risk-centric assessment methods like risk registers. Huge problems are frequently missed. Few internal auditors provide boards with concise reports on the likelihood or risk that key objectives will be achieved while operating with a level of risk and certainty acceptable to the board.

THE WAY FORWARD

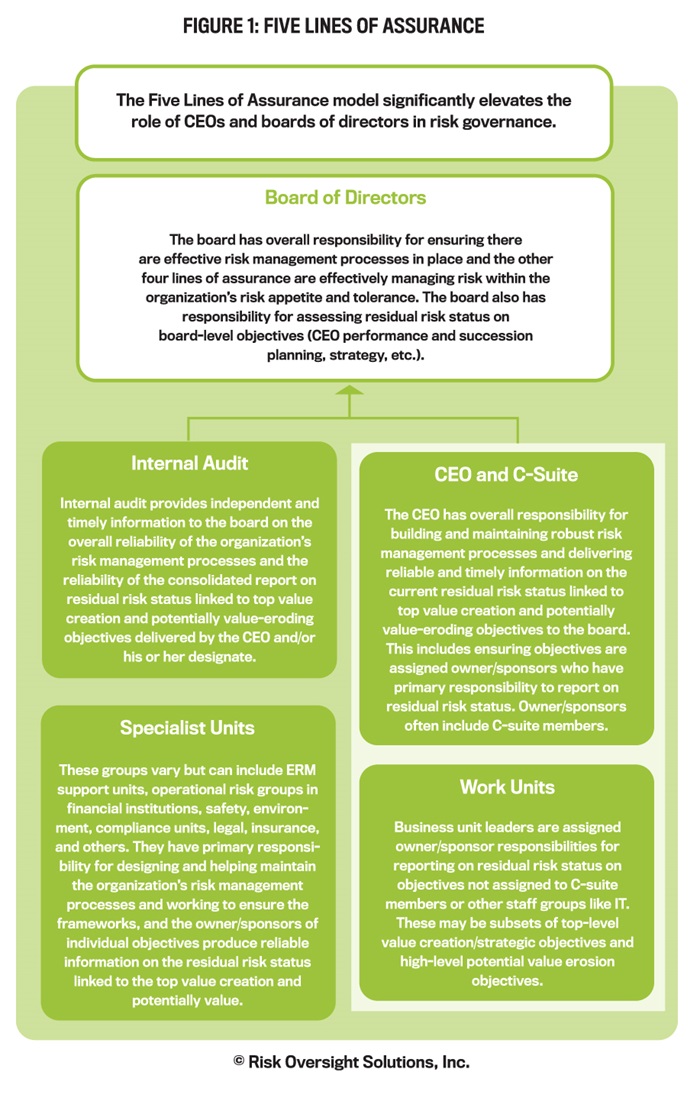

The Five Lines of Assurance (see Figure 1) takes a different view on roles than the Three Lines Model. The focus of the Five Lines of Assurance is on assessing, managing, and reporting to the CEO and board on the likelihood and risk that top strategic, value-creation, and value-preservation objectives will be achieved within the risk limits and tolerances acceptable to the board.

In this approach, management (the first line) is the primary risk assessor and reporter. Second-line functions, including risk groups, help management assess and report on risk and certainty status. Third-line internal audit assesses and reports on the effectiveness of the risk assessment/reporting process and reliability of risk status information linked to key objectives going to the board.

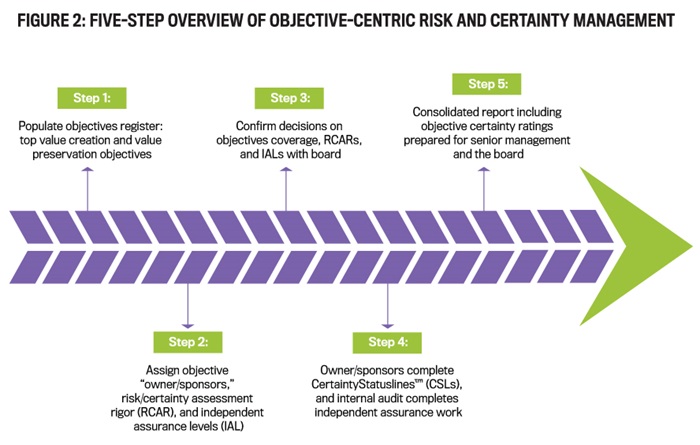

Implementation of this strong first-line, objective-centric, demand-driven risk governance is relatively simple (see Figure 2). It starts with management and the board agreeing on the objectives key to the entity’s long-term success (objective-centric risk management) and assigning management “owner/sponsors,” the people responsible for assessing and reporting upward on risk and certainty status (strong first line).

Objectives in an entity’s “objectives register” may include environmental, social, and governance (ESG) objectives in cases where the company considers ESG to be part of its top strategic and value-creation and/or value-preservation objectives. Decisions are also made on the target level of risk assessment rigor (the amount and sophistication of methods used to assess the state of risk linked to key objectives) as well as the target level of independent assurance from internal audit and other assurance providers that the CEO and/or board want on risk status reports they receive on key objectives (the demand-driven element).

THE PARADIGM SHIFT

We recognize moving to strong first-line risk governance represents a paradigm shift for most organizations today. So, what is the business case for change?

Driver #1: Reduce the number of repeated and colossal risk governance disasters. Most companies that have had colossal risk governance failures over the past five decades had traditional internal audit functions. Few internal audit functions today provide concise information to boards on the composite effect of risks linked to achievement of mission-critical objectives to help boards decide whether they’re aligned on and agree with management’s risk-acceptance decisions.

More recently, companies—particularly banks like SVB—have been forced by regulators to have risk functions and chief risk officers. Most of these risk functions produce lists of top risks to boards with little linkage to key mission-critical objectives or performance. Few risk functions today provide boards with information on the composite effect of risk on achievement of key mission-critical objectives.

Strong first-line risk governance places the accountability for assessing and reporting on risk status directly on management, the people best positioned to assess and monitor risk status linked to key objectives. Second-line risk functions help the first line assess and report on risk status to the CEO and board. Third-line internal audit provides objective assessments of the risk management process and reports on risk status linked to key objectives going to the board. Moving the responsibility to assess and report to the first line is particularly important in high-change environments.

Driver #2: Provide boards with reliable risk status reports on mission-critical objectives to help discharge escalating risk oversight expectations. Courts, particularly in the U.S., are increasingly holding that boards and, more recently, “officers” of listed public companies (see the Caremark and Blue Bell Dairy decisions) have a fiduciary duty of care to oversee mission-critical objectives and risks. Financial sector regulators are increasingly codifying expectations that boards have a legal duty to oversee management’s risk taking in pursuit of strategic and value-creation objectives and top value-preservation objectives.

Driver #3: Evolve the role of risk and internal audit from that of “risk police” to a more productive and effective peer-to-peer interaction. For systems to work effectively, they need to have the type of aspirational attributes and “risk culture” described by Horta-Osório. Companies that want management at all levels to see themselves as risk managers and reporters need to take tangibles steps to assign the responsibility to assess and report on risk status linked to key objectives to those who are responsible for achieving those objectives.

Because assessing and reporting on the risk linked to key objectives is a new responsibility for many first-line executives, management needs training, facilitation, and support. Managers in companies around the world need to develop better, more structured ways to identify and assess threats and opportunities linked to key objectives.

Second-line risk can play the primary role helping first-line management assume these new responsibilities. Third-line internal audit can play the role of the second line in companies with no risk function and can provide independent assurance and advice on how objective-centric risk management processes are working.

Driver #4: Improve performance. When risk and opportunities are managed well, there’s greater certainty that key objectives will be achieved at a level of risk acceptable to the CEO and board. When risk assessments are objective-centric, they detail the objective being assessed; internal and external contexts; the threats and risks, including likelihood and consequences; risk treatments in place linked to those risks; and “residual risk status” information, including performance history and impact of not achieving the objective in whole or in part. The goal is to increase the likelihood that key objectives are achieved while operating with a level of risk and certainty acceptable to the CEO and board.

Driver #5: Reduce the cost of inspection. Build quality in, not on. Manufacturing sector and safety specialists learned a long time ago that positioning process analysis and improvement directly with work teams is key. At the same time, companies around the world have been steadily increasing spending on second-line risk, compliance, internal audit functions, and, most recently, ESG groups.

In companies where management demonstrates integrity and competence in assessing and reporting on the risk status of key objectives, the spend on third-line internal audit can be reduced or redeployed to instances where management consciously misstates the true risk status.

STRONGER FIRST-LINE RISK GOVERNANCE

The recent bank failures have reminded us yet again that the current dominant approach to risk governance isn’t adequately fulfilling its purpose. Weak first-line risk governance, coupled with excessive reliance on second- and third-line functions like risk groups and internal audit to identify, assess, and report on risk, creates a potential disconnect that can prevent a company’s board of directors from receiving the information it needs to fully understand and monitor the risks linked to key objectives and to provide appropriate oversight to ensure whether management is taking the proper courses of actions.

Changing the paradigm to a strong first-line risk governance approach—where management must identify, assess, and report to the board any risk decisions or concerns—not only creates a clearer, more direct line of communication but also places accountability where it should be. The ultimate result would be better-informed decision making and fewer company failures—a result that all stakeholders would appreciate and value.

July 2023