Navigating the whims and cycles of the market can feel like a roller coaster, especially for newer companies. One moment you’re soaring to new heights with rapid growth, and the next, things are plunging down and layoffs are seen across the board. Then, before you know it, growth is up again, and more people need to be brought on to climb that hill.

How can you know when it’s time to focus on growth and when it’s time to conserve capital—before the layoffs or delays happen? You want to hire the right talent and invest in people who will provide a return on the capital you spend but in a manner that won’t end up constraining the organization down the road. Scaling up smarter is possible—so let’s look at how to go about it the right way.

PLANNING FOR SELF-SUSTAINABILITY

To achieve their targets, companies typically plan for and evaluate risk and return trade-offs among three types of execution strategies: growth, moderate, and conservative. In the growth stage, all systems are go: The expectation is that new customers are out there ready to be converted, and the economic environment around the company and its industry is conducive to aggressive maneuvers. Maybe capital is cheap, or a competitor just moved away from the market, or customer interest in the product is on the upswing. On the other hand, a conservative growth strategy is one with scaled-back initiatives, more concerned with maintaining current customers than searching out new ones or making risky moves. Moderate strategies are, of course, a combination of the two for when some signs suggest areas to push for rapid growth while others look less rosy in the short term.

These strategies determine the optimal level of investment and capital allocation decisions at any given time. Companies will continuously move between these execution strategies as time passes and as micro- and macroeconomic circumstances evolve. Planning for and picking the right execution strategy today can have a material impact on how successful a company will be in attaining its near- and long-term goals.

Cash is always a priority. Look at cash flow, how much money is on hand today, and how much of it goes to critical vs. noncritical functions. If you have enough runway to last three to five years, it might make sense to act more growth-oriented rather than conservatively. Establish guardrails in each scenario (one for a growth-minded approach as well as moderate or conservative ones)—consider, for example, how much capital you’re willing to allocate and the expected return on said capital—and continuously monitor business performance against these guardrails to ensure efficient capital allocation as well as sufficient remaining runway. If you’ve entered a growth stage but then run out of cash, you won’t be able to scale and take advantage of the opportunity.

The goal is self-sustainability: making more money than the company spends, i.e., being cash flow positive. That sounds trivial—that’s what all businesses should be striving toward, ideally. Yet often many start-up companies, despite having raised significant external capital, are still far away from being cash flow positive and have to rely on additional debt, equity, or other forms of financing in order to sustain operations, a difficult task in today’s economic environment.

At organizations I’ve worked with, I’ve found a five-year growth plan to be the best way to find a path to that point of sustainability. Five years tends to be the longest you can forecast to some degree of certainty. Anything beyond that window is unreliable, especially in fast-growing industries. And when you take into account the instability of the world in recent years, these growth plans will be essential as you tailor your activities, especially hiring, to the uncertainty we’re up against.

As you model your five-year plan with the goal of getting to the breakeven point and making money without the need for additional capital infusion, there are a number of factors to consider—knobs to turn, if you will, that will change the trajectory of the plan. Those include how much to invest in sales infrastructure, how much should be spent on active pipeline generation, and what to put into product and operations functions that don’t have a direct line to sales but do support the company and/or your go-to-market strategy.

There’s no cheat sheet here; I can’t say, “Spend 10% on support staff, 25% on your pipeline,” and so on, because many factors influence what the right allocation of spend will be—as well as what the overall amount of spend should be for a given quarter or year. Things like a company’s competitive standing; its existing infrastructure; and seasonal, global, and social changes all affect the need for different parts of the company to receive finances and focus.

For example, if market share is slipping, it could be because consumer taste has started to move away from a company’s offerings and more spend should be allocated into making sure the product team’s finger is on the pulse of the customer. Or if the company’s business is greatly affected by an event that doesn’t happen every year, like a presidential election or a World Cup tournament, the spend allocation should look different on “off” years than it does in the year leading up to the event.

This also speaks to the need to dynamically update the five-year plan regularly at quarterly or yearly intervals. As the world changes over time, so does your industry. Does your plan still work for the environment you find yourself in, or does it need updating? Those reviews should also evaluate the performance in the previous period against the targets that were set. Did you get where you wanted? Was the spend on target, or did you overspend? What does that say about the upcoming period’s plan?

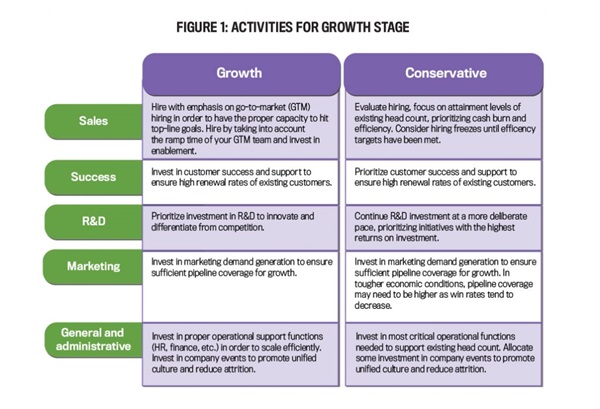

An increasing number of companies now work on subscription models, so comparing the annual recurring revenue that was added in a period to the amount of cash that was spent to acquire is important. Understanding your “burn multiple” will help inform the budgeting process, as it shows spending efficiency and can help to identify aspects of the organization that require more investment based on efficiency and return on spend.

Work backward and in chunks of time as you plan out. For example, if you want to make outcome A happen by year five, capability B needs to be in place by year three, and thus initiative C should be up and running by one year in. It can be a lot easier to see what you need to do today to get to that first checkpoint in year one than trying to sort out how the details today will get you to year five.

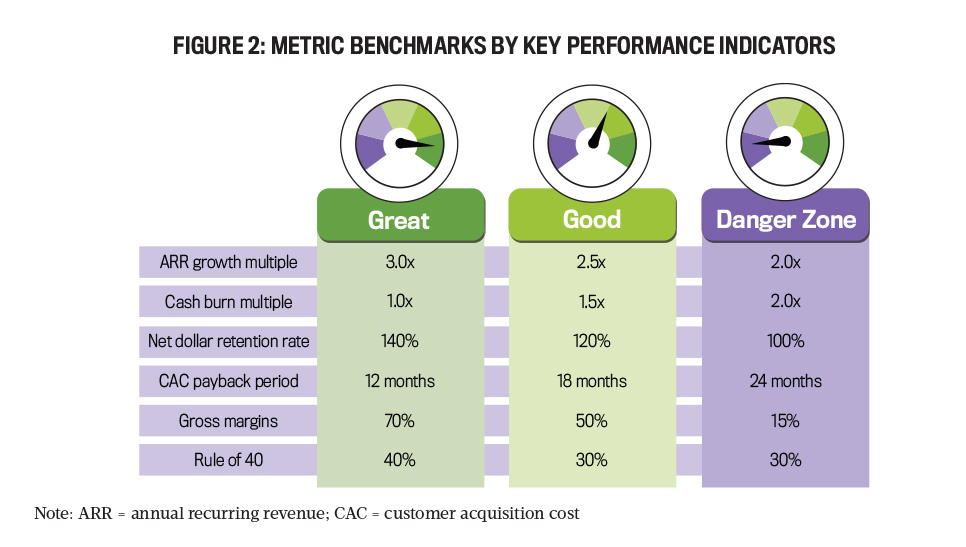

And it’s important to remember to filter every decision in your planning by the stage your company is in at a given point, leaning toward more aggressive spending as you enter growth phases and pulling back as you exit them into other stages. Many companies would benefit from creating three parallel five-year plans: one looking at the path ahead through a growth lens, as well as two others that take moderate or conservative views of the upcoming years. (See Figure 1 for more on what a company can do in the growth and conservative stages.)

TEAM BUILDING

Beyond having a plan, you need to make sure you have the proper team in place to execute that plan. That doesn’t just mean “hire like crazy,” though; you have to get the right people at the right time.

In certain sectors, we see huge hiring runs that companies and the entire industry go on over a stretch of time. An investment round comes through or a forecast looks particularly rosy, and companies “staff up”—fast. Companies that are able to raise money quickly often deploy it just as quickly, which can lead to cash flow problems later on. This is particularly true when, in the rush to hire as many people as possible, they aren’t taking the time to hire the right talent: people who will provide a return on that investment. These companies end up hiring employees that don’t fit with the culture or provide what the company really needs in the coming years. That’s a surefire way to kill momentum. Even when the cash flow is good and the company is in a growth stage, it could lead to further disruptive layoffs. Churn is expensive, so avoiding it at all costs is advised.

Think about how your company is attracting top talent and how it retains it. You must make the proper investments in your team—head count is only one part. Hire strategically, not quantitatively; two people who fit perfectly will add more to the company than five snagged right away so that they can get to work quickly.

Part of properly investing in your team is what happens after they’re on board. Compensating them fairly; keeping them motivated with financial, career-based, and aspirational rewards; and recognizing their hard work go a long way toward a happy and productive team. Some people are motivated by different things than others, so being attentive to the needs of your team and flexible in the ways you take care of them will be impactful.

Productivity is the key thing you’re looking for when building your team. There are individual markers of productivity, of course—an interview process and referrals can help you determine how productive each potential employee will be at a baseline level. But it’s important to assess how someone aligns with your company’s vision and mission overall. Those who don’t align are likely to be less intrinsically motivated in the role and might detract from the belief in the company mission that their peers have. On the other hand, bringing on employees who believe in the company’s overall mission and want it to succeed are thus more likely to go above and beyond to make that happen. We’ve seen productivity from these individuals increase over time, and their input is higher in the second year than it is in the first.

With many more people remote and departments decentralized these days, it’s important to make sure workforces are incentivized to be part of something grander. That mission previously mentioned should be one that anyone working at the company should be proud to have their name associated with. It should be aspirational, positive, and easy to comprehend. When an acquaintance asks an employee what they do for a living, ideally some form of the mission should be included in the reply. If they say, “I work for a company that makes telehealth tools,” they aren’t feeling their place in the bigger picture. But if they respond, “I help make it possible for people who live in rural areas to have reliable, quality access to healthcare that they wouldn’t otherwise have,” it’s clear that person has a connection to the greater goals of the company.

Company culture means a lot when it comes time to grow, hunker down, or change tactics. It means people will follow leadership into the new plan. When you invest in good people and good leaders, and you take care of them, you’ve set the foundation for good company culture. When internal disorder occurs, productivity is often the first thing to take a hit.

As your company grows, you can keep that culture strong by taking care to make all employees feel seen and welcome. This is just one of the many nuances of building a good company culture, a foundational aspect of a company, and it’s important enough that if you’re going to scale your organization, take the time and effort to get it right.

The stage of growth the company finds itself in makes a difference in hiring and retaining activities. If you’re in a full-on growth stage with plenty of runway, you can be more aggressive, whereas a company in a conservative stage with only six months of cash has to make every dollar count.

You’re looking to build flexibility and stability in your team, and keeping team members happy and on board is a key part of that. A more remote workforce like we have today creates an environment of “always hiring”; the average tenure of an employee is at risk of going down given how many options are now available to them and how competitive the labor market is. You can’t control that remote environment across the industry, so focus on what you can control: making your team one that people clamor to be a part of and one they want to stay in once they’re there.

FITTING INTO THE MACROECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT

If you’ve been feeling like things are a little unstable economically and geopolitically lately, you aren’t alone. (See “CFOs Prepare for 2023” in our digital issue, on p. 26 for more on what’s top of mind for CFOs.) Volatility had been increasing before the pandemic, but now it’s everywhere we look. Every day, something else is shaking the foundations of even the best-laid plans.

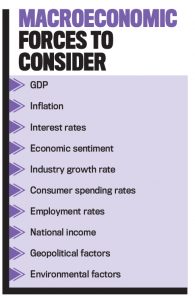

The fact is there’s a certain level of risk and uncertainty that you simply can’t hedge against. That goes double for industry-specific risks that layer atop those larger, systematic risks. Ultimately, the stage of growth your company is in and the larger macroeconomic climate need to be considered together when making moves to scale. With inflation high and recession looming, in a competitive vacuum, it might be a good time for businesses in some industries to take a conservative growth strategy for the moment. But that ignores the reality that there are competitors out there angling for larger portions of the same—potentially shrinking—market.

Think back to the pandemic, how many of the restaurants that survived—or even thrived—during that time were ones who turned up their spend in specific areas. Investing in curbside and delivery options turned out to be a savvy move to gain market share, as was the use of “ghost kitchens” on delivery apps—essentially creating a new brand through which to sell food.

Keep an eye on forward-looking indicators. Ask yourself questions that can help determine whether or not being aggressive now will be the right move a year or two later. For example, are you able to fill the sales pipeline with quality leads, and are you able to convert that pipeline into paying customers at the same level that you historically considered a sign of robust growth? If not, a closer evaluation is needed.

Is it an overall economic condition causing those numbers to drop off? Is the average person’s budget too tight so that the product you’re selling is less in demand due to being inessential during lean times? That could be a product strategy conversation worth having and will also inform the way you scale in the coming years.

Every decision should be weighed against your company’s macroeconomic and competitive environment simultaneously. (See Figure 2 for more metrics for assessing your organization’s position and growth planning.) If your competitors are ramping up to go after market share despite other factors, should you do the same? There are risks to taking that leap but also risks to staying put and leaving that ground uncontested. How fast your competitors are growing should inform your product and growth strategies.

If you do decide to scale, take a smart approach. Review your pipeline and deal cycles and identify the segments of the deal process that you could focus on better. If your competitors are spending their capital to grow, you can get the upper hand by deploying your own capital in a smarter way. It’s important to do this right: It’s easier, after all, to ramp up from a conservative stance to an aggressive one than it is to go in the other direction—reducing costs and layoffs.

Focus on the productivity and efficiency of your internal team and on taking care of your existing customer base. It’s more expensive to acquire a new customer than it is to nurture an existing one so they’ll buy more, and, similarly, it’s more costly to hire new employees than train the ones you have for bigger and better things.

Putting these concepts into practice—investing in existing infrastructure, deploying capital efficiently, adapting for the macro environment while maintaining pipeline and conversion rates, and keeping an eye on forward-looking indicators—will help you identify the right way to be aggressive even in the face of uncertainty.

In order to achieve their targets, companies typically plan for and evaluate risk and return trade-offs among three execution strategies: growth, moderate, and conservative. These strategies determine the optimal level of investment and capital allocation decisions at a given time. How they navigate between these strategies is a major factor in determining when it’s time to scale up and when it’s better to take a more measured approach to growth.

Building a five-year plan that’s dynamic, evolving, and evaluated on a regular basis will go a long way toward effectively working toward a goal for scale—for many companies, that goal will be self-sustainability. It’s recommended that all five-year plans be assessed through a different lens for each of the three growth stages so the plan can be evaluated and acted upon based on which stage the company finds itself at a given time.

Hiring the right individuals for your team, at the right time, is crucial to executing that plan effectively. Invest in your people, and scaling will be a smoother road; if you don’t put enough into them, or you wind up with employees that don’t align with the company mission, momentum could be dashed and a number of other problems will keep you from efficiently scaling.

Macroeconomic and competitive forces are the other major considerations that impact whether it’s the right time to scale. (See “Macroeconomic Forces to Consider” for a starting list.) Keep an eye on what the competition is doing and weigh the risks out there, both in your industry and beyond it, against the risk of letting competitors grow unchallenged. Use forward-looking indicators to assess whether scaling today will be a smart move come tomorrow.

These principles can serve as a reliable guide to scaling through what is often an unpredictable roller coaster, regardless of industry. By planning your moves and backing up your decisions with careful consideration of these myriad factors, your company can forge ahead and grow even through uncertain times.

January 2023