This article is based on research funded by a grant from the IMA® Research Foundation.

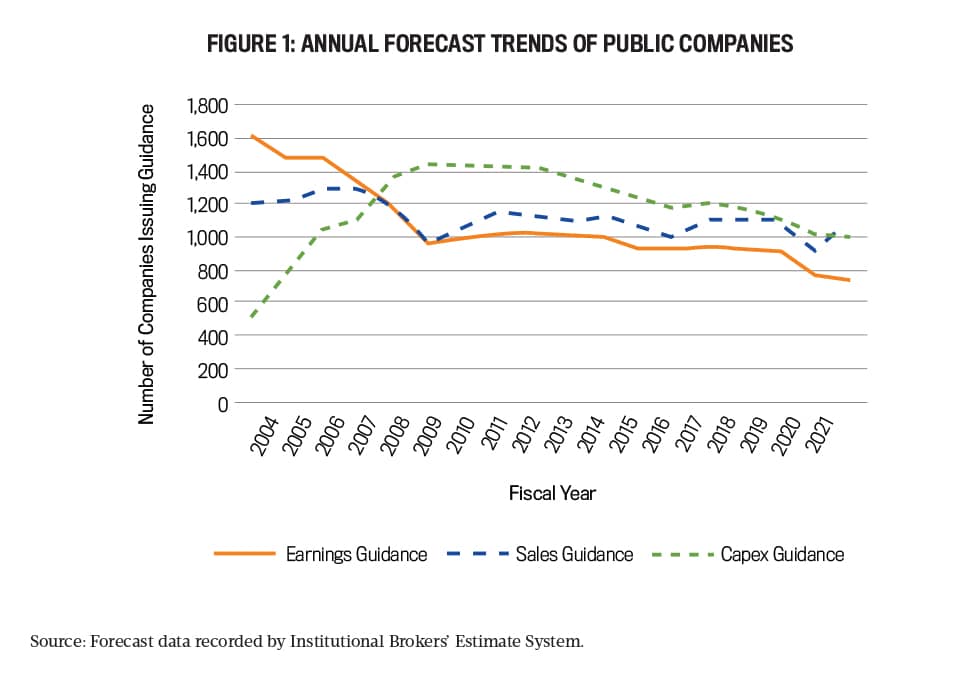

Plenty of focus is given to earnings targets in the popular press, but the discussion around capital expenditure (capex) targets is limited at best. This lack of focus is puzzling because the practice of disclosing capex forecasts has become widespread: Annual capex forecasts have been more common than annual earnings forecasts for more than a decade (see Figure 1).

This changing trend coincides with investors’ and executives’ growing criticism of short-termism prompted by earnings targets (see, for example, Jamie Dimon and Warren Buffett, “Short-Termism Is Harming the Economy,” The Wall Street Journal, June 6, 2018). But shifting from earnings myopia to a future focus has its own challenges. Capex forecasts represent a company’s longer-term strategy for securing future economic benefits, but capital expenditures represent opportunities that are new and uncertain and are therefore riskier ventures than managing short-term earnings efforts. If managers don’t appropriately address uncertainty in capital projects, they can derail long-term operating returns.

Learning and applying best practices for forecasting and project execution facilitates sustainable success despite known and unknown risks. Along with outlining best practices, we hope to motivate increased collaboration between project managers, the financial planning and analysis (FP&A) function, and executives and boards to achieve better future performance.

Executives are responsible for the selection and execution of risky yet profitable projects. Yet capital portfolio management is an elusive skill—even talented executives can preside over disastrous projects plagued by cost overruns and completion delays, which ultimately result in poorer returns than originally planned. A notable example involves Barrick Gold Corporation, whose capital project overruns in the early 2010s contributed to the abandonment of its Pascua-Lama project, which management had promoted as eventually becoming a world-class mine. The dysfunction in this megaproject attracted lawsuits from shareholders claiming Barrick Gold Corporation misled them since, as a builder of mines, its executives should have better known and managed the risks of their project portfolio. As challenging as FP&A is for short-term earnings, it can be even more difficult for capital project portfolios.

Capital expenditure planning analytics are difficult because of the greater risks inherent in project portfolios. Although some projects are merely high-dollar maintenance costs that meet capitalization thresholds, other projects introduce numerous complexities that make their execution more difficult. Overall, capital project management typically lacks the familiarity and historical predictability that’s accessible for sales and operations planning. Their future operating returns are thus somewhat nebulous, which requires different types of management practices to ensure they come to fruition.

Management accountants and FP&A professionals, as well as boards of directors and company executives, can adopt best practices in capital portfolio analytics to improve future operating returns. These practices involve moving away from traditional, more rigid control-focused planning analytics to more flexible emergence-focused planning analytics.

When management adopts more emergence-focused paradigms, the natural outcome includes consideration of multiple potential scenarios, preemptively planning how to respond to those scenarios, and then adapting to scenarios as they materialize. Accounting for uncertainty requires moving away from providing point estimates and results in considering many possible outcomes, which unfolds into range-based reporting. Additionally, adaptive risk management during portfolio execution prompts continuous learning, which in turn results in frequent forecast revisions.

TRADITIONAL CONTROL-FOCUSED PLANNING

According to cost engineering’s recommended practices, there are stark differences between deterministic and stochastic planning (AACE International Recommended Practice 10S-90, Cost Engineering Terminology; and John Hollmann, Project Risk Quantification, 2016). Traditional capital portfolio planning presumes a root of determinism and accountability for the economics and deliveries of projects: Individual projects are analyzed with straightforward net present value (NPV) calculations given a set of economic assumptions, and then the costs, schedules, and revenues of the organization’s projects are aggregated to the portfolio level. Managers then assess, modify, and approve that single capital expenditure budget. Resources are then allocated with the understanding that budget variance analysis will be one of the tools to assess project performance. This deterministic, control-focused approach emphasizes accountability for the capital project plan as work progresses. The outcome of this accountability mentality is the focus of managerial effort on planning and execution to keep projects on time and at or below cost.

This deterministic approach is simple and cost-effective. It drives favorable project outcomes when the project portfolio consists primarily of capital projects that are repetitive and executed in a relatively stable business environment. For example, traditional capital portfolio management could be adequate for a retailer whose projects involve opening new stores in familiar locations and, accordingly, its managers can roll forward historical data based on their project expectations. Yet project plans founded on determinism and accountability almost always fail in delivering more complex capital portfolios on time and under budget, let alone eventually generating future operating returns.

With traditional capital portfolio planning, a strange but recurring event is that even when organizations “achieve” their capex target, the costs of portfolio accuracy include compromised future operating returns. As cost engineering consultant John Hollmann asserts, “Often, the worst project systems will hit exactly their total budgeted amount.” Pressuring or incentivizing management teams to spend what they committed to spend redirects the focus away from the fundamental, overriding metric of a project’s success: whether it helps the organization’s future returns.

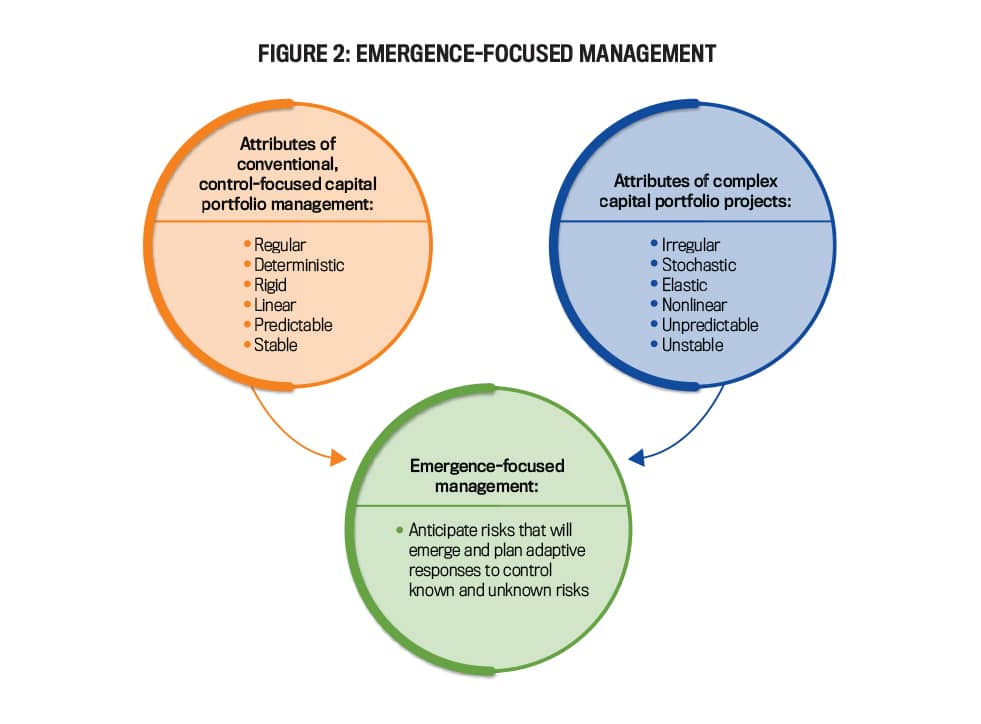

To increase capital budgeting success, executives must embrace not just improved analytical tools but also the different paradigms that form the foundation for their success. Emergence-focused management and analytics (see Figure 2) and their underlying paradigms can help leadership and management achieve their risky project portfolios’ future operating returns. This approach acknowledges that previously unknown risks can emerge after the pursuit of an opportunity has begun, requiring flexible processes to plan risk responses and adapt to new risks. Some traditional controls still carry forward into emergence-focused management (such as due diligence with supplier selection, developing baseline estimates, etc.), but these tools are supplemented with paradigms that acknowledge a portfolio’s systemic and idiosyncratic risks, utilize risk quantification and response planning, and focus on future operating returns.

EMERGENCE-FOCUSED PLANNING PROCESSES

Although many companies use the traditional capital portfolio system archetype, others have developed mature, flexible capital portfolio management systems with teams that have strong capabilities to mitigate project risks. These systems focus on emergence (meaning learning and adapting to risks throughout project execution) rather than emphasizing control (wherein managers try to force projects to behave as originally modeled).

The advanced approach fits well with the 2017 version of the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission’s Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework, wherein an organization’s goals dictate its control selection process. Here, project stewards and stakeholders alike dismiss the assumption that the senior leadership team can simply hold managers accountable for original budgeted amounts and schedules. Rather, more advanced approaches recognize that new risks will arise during the execution of projects.

Acknowledgment of the emergent nature of capital portfolios encourages managers to exercise real options on underperforming projects by deferring or abandoning them. In this context, the term “emergent” refers to identifying previously unanticipated risks that threaten future operating returns. Thus, management’s understanding of and adapting to those risks emerge during project execution. The emergence-focused process complements rather than substitutes for traditional control-focused planning processes (Robert Wiltbank, Nicholas Dew, Stuart Read, and Saras D. Sarasvathy, “What to Do Next? The Case for Non-Predictive Strategy,” Strategic Management Journal, October 2006).

When applying emergence-focused analytics, the original single aggregated portfolio estimate is just the starting point. Once analysts validate this estimate as a true baseline, then more advanced analytics can begin. The more advanced analytics’ outputs are feasible ranges of (1) capital expenditures, (2) schedule durations, and (3) profit realizations. Knowing potential ranges in these three areas helps management to monitor portfolio progress and adjust resource allocations as needed, for example, knowing the range threshold for new cost estimates that push future profits into future losses.

The consensus among expert project engineers and cost estimation practitioners is that some of the strongest predictors of a project’s economic success (profitability) once the project enters the operations phase are (1) the initial conditions under which the project commenced, (2) the strength and maturity of the project delivery team and system, and (3) the proactive risk management through continuous and rigorous analytics. These factors become even more relevant in complex projects (Lan Luo, Qinghua He, Jianxun Xie, and Delei Yang, “Investigating the Relationship between Project Complexity and Success in Complex Construction Projects,” Journal of Management in Engineering, March 2017).

While classifications of complexity may differ by industry or practitioner, some common types of project portfolio complexity include organizational, informational, technological, and environmental complexity as well as task and goal complexity. These and other complexities not only shape capital portfolios’ initial conditions but also interact with each other during execution, producing stronger negative effects on returns. Consequently, the analytics function in highly complex capital project situations should facilitate saving the portfolio from downward performance spirals and project blowouts.

Clarity of communication is tantamount between project proposers (business segment managers, project teams, and project contractors) and project customers (FP&A teams, senior management, and the board of directors). To establish foundational understanding that can translate into strong business synergies, management accountants can help to remove the “Babel” effects when various stakeholders meet. This is the miscommunication that arises from using unfamiliar language or terms—or even when different disciplines have different meanings for common terms. Given that project planning and execution teams are inherently heterogenous, this kind of misunderstanding happens easily and should be eliminated as much as possible.

One such example is the difference between “control” and “emergence” discussed previously. Another involves the difference between “escalation” and “inflation.” Cost escalation in a project setting represents the additional costs incurred when inputs become more urgent or demand higher quality than originally estimated. Inflation simply refers to the increased price of a basket of goods and services. Hence, inflation is one of the many factors that can cause cost escalation.

Another crucial understanding management accountants can help to reinforce is that accountability for the results (including informed risk mitigation) still resides with management—regardless of whether the project execution team is in-house or outsourced.

AN OUTLINE FOR EMERGENCE-FOCUSED ANALYTICS

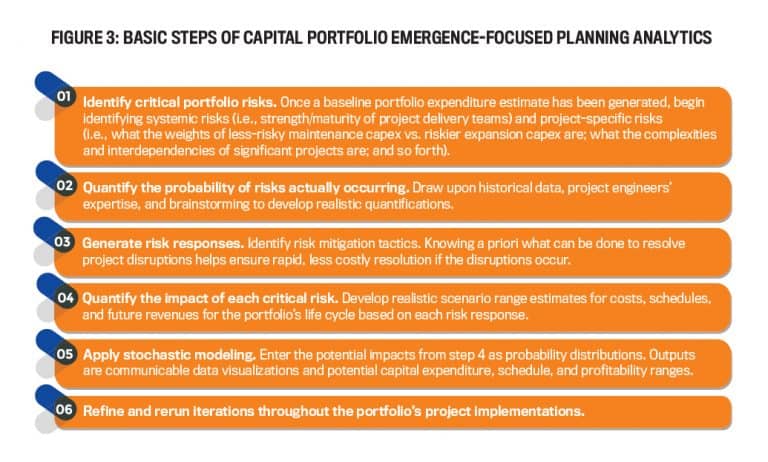

Figure 3 outlines the six steps for capital project portfolio analysis. We have adapted these from John Hollmann’s 2016 book Project Risk Quantification and unstructured interviews with Hollmann from April 15, 2020, through July 1, 2020.

Step 1: Identify critical risks. One of the critical risks is systemic risk, which relates to the maturity of an organization’s project delivery system, how well that system defines and manages project scope, and the strength of project delivery teams. Systemic risk is the likelihood of project failure due to inherent shortcomings of the company’s project execution resources and processes. The baseline portfolio estimate, which is the aggregation of each individual project’s best estimates, is incomplete without incorporating risk factors for cost, schedule, and profitability that are likely to occur based on systemic risk.

Systemic risk ties to phenomena that have consistently occurred in the past but remain excluded from baseline estimates and, thus, routinely disrupt projects. Systemic risks are the biggest source of project uncertainty. Idiosyncratic risks, on the other hand, are specific to the project. Some examples might include clarity of project objectives, size of the project, quantities of work-breakdown-structure elements, quantity of suppliers or contracts, extent of construction interdependencies, interconnection with other projects, unfamiliarity of technology, realism of assumptions, and external market uncertainty. All of these could prompt additional cost overruns, schedule delays, and profit reductions.

Step 2: Quantify probabilities. The next step is to quantify the risks that can occur and assign probabilities to their events. Because risk quantification is challenging, brainstorming and using historical data can help with this effort. This step should involve honest and realistic assessments.

Step 3: Generate risk responses. For each of the capital portfolio’s risks, preemptively determine the responses should it materialize. These responses could include actions such as allocating more staff, increasing funding, ceasing other project phase activities to focus on a specific troubled area, and so forth. To reduce adverse project selection and escalation of commitment, each analysis must consider the economic effects of postponing or canceling the project.

Step 4: Quantify potential impacts. Solicit expert opinions to develop scenario range estimates for cost, schedule, and future profits over the project life cycle (which includes its prospective operating profitability) based on each risk response. It’s important to integrate direct, indirect, and time-dependent cost and profit impacts during this step. Then, management should discuss the realization and potential severity of the impacts based on prior performance and future unknowns. All these potential outcomes should consider organizational constraints and objectives—that is, target rates of return, debt covenant stipulations, financing available from operations vs. ability to raise external financing, etc.

Step 5: Apply stochastic modeling. Analysts must enter the potential impacts from step 4 as probability distributions multiplied by the potential impacts on the project portfolio. Project management teams should also perform this analysis on larger individual projects. The subsequent capital expenditure ranges of potential project portfolio outcomes over time become expected ranges of capital forecasts for a specified period.

- Portfolio Costs = Baseline Costs + Impact Risk Γ * Probability Distribution Risk Γ + …

- Portfolio Schedule = Baseline Schedule + Impact Risk Ξ * Probability Distribution Risk Ξ + …

- Portfolio Revenues = Baseline Revenues + Impact Risk Ω * Probability Distribution Risk Ω + …

Analysts should present the data outputs both numerically and visually for the portfolio’s possible scenarios (a useful tool for this is Palisade’s @Risk add-in for Excel). Stakeholders often benefit when analysts perform these tests frequently, especially during more volatile business environments. Because the outputs of these tests are ranges, management can assess the business impact at various predicted outcomes and generate additional risk mitigation strategies.

Step 6: Refine and rerun. Since risk management is an ongoing process, project management teams and planning analysts should repeatedly follow steps 1 through 5 throughout portfolio execution. For example, management can decide to reserve funds for risks that have a high impact despite being low-probability events, remove these risks’ variables from the model, and then rerun the analyses to assess the less drastic scenarios.

These steps provide the senior leadership team with more informed decision inputs regarding their internal capital investment activity and help them guide the expectations of external stakeholders through disclosures that are more informative. With all these analyses, reality checks are crucial. If the company has maintained historical data for original estimates and projects’ actuals, it’s worthwhile to use this data to regress cost increases, schedule overruns, and revenue drops on potential explanatory variables to help identify recurring risks unique to that company’s portfolio. Significant coefficients from these regressions will also help inform the systemic project risks identified in step 1.

Additionally, there are other critical high-level questions to ponder for a comprehensive risk assessment of the capital portfolio:

- What will the enterprise-wide impact be if, for example, the larger, more crucial projects go over cost or schedule by 100% to 300%?

- What external financing access is in place to reduce the likelihood of project churn?

- Have we thoroughly documented and quantified the highest risk and highest impact complexities?

Retaining traditional project controls, including final project outcome assessments of budgeted vs. actual capital expenditure, can undermine the effectiveness of emergence-focused systems. Traditional project controls frame variances from original budgets as poor performance, but emergence-focused systems affirm deviations if they preserve the project’s eventual operating returns.

Companies should also modify evaluation processes to increase the effectiveness of emergence-focused control processes. For example, instead of benchmarking against budgeted capex for the year, performance evaluation of managers could be based on the thoroughness of portfolio risk quantification, the speed of implementing predetermined risk responses, clarity of focus on future returns, and the identification of projects that require abandonment. Otherwise, organizations will forego the value creation that can arise from implementing these capital expenditure planning analytics. In short, flexibility and adaptiveness are key for an emergence-focused approach.

BENEFITS FOR CAPITAL PORTFOLIOS

The application of emergence-focused management tools requires a shift in thinking from the assumptions underlying traditional planning and accountability systems. Large, successful companies have applied more emergence-focused approaches. Multinational oil and gas company Shell plc modified its project execution processes as early as the 1960s to include portfolio scenario analysis. Similarly, mining company Newmont Corporation, one of the world’s top two gold producers, utilizes stochastic modeling for its capital project portfolio, which results in ranges of its forecasted capex being disclosed to the public. Stochastic modeling and its outcome, adaptive risk mitigation, are empirically associated with enhanced operating performance.

Yet emergence-focused project analytics aren’t a panacea. As Hollmann describes in Project Risk Quantification, the joint rigor of project management and FP&A teams can be negated if managers under-allocate resources for projects or if the teams don’t earnestly seek expertise in risk quantification and mitigation. Further, a more traditional deterministic approach may be adequate if the capital project portfolio has simpler projects, such as recurring high-dollar maintenance spend or projects that replicate past projects.

Emergence-focused analytics may be used to facilitate communication and decision making between project management professionals, the finance function, project sponsors, and the organization’s stakeholders when there’s a greater proportion of unique, large, uncertain, and complex projects in the portfolio. This approach is particularly relevant in the current volatile business environment for companies that want to secure more sustained future operating performance.

January 2023