Companies’ understanding of dealing with the uncertain future has changed considerably in recent years. This has significant implications for the current approaches to risk management, whether it’s part of the duties of the finance department or the responsibility of a dedicated function.

This new understanding raises the question of whether risk management is redundant. Simply asking that question, however, will immediately raise the eyebrows of most risk, compliance, and audit professionals. Risk management has been long established as something that can and should be implemented—to not do so is considered profoundly unwise. It saves you from unnecessary pitfalls. And above all, risk management helps you achieve your goals. So why would it be redundant?

Risk consultants keep selling their services—risk frameworks, risk assessments, risk registers, risk matrices, risk dashboards, the list goes on—and many organizations continue to buy them. All these services are designed to capture, analyze, and address risk. Tim Leech (riskoversightsolutions.com) and others refer to this approach as “risk list management.” The ultimate goal is to mitigate what can go wrong.

Yet as Alexei Sidorenko (riskacademy.blog) and others point out, risk management isn’t really about dealing with risk but rather about making better decisions. Therefore, to what extent do decision makers need separate risk management if the following conditions apply?

- Looking ahead and considering the uncertain future is part and parcel of their regular management responsibilities. They ask questions like “What can happen that could help or hinder the realization of our objectives?” They understand that their objectives are about creating and protecting value for their core stakeholders. They try to make realistic estimates of possible positive and negative impacts of what can happen on the interests of their stakeholders.

- They demonstrate that they’re consequence-conscious. They’re aware that there are options to act or to refrain from acting. They consider the possible consequences of their options on the competing or even conflicting interests of their stakeholders. They take unwelcome information into consideration as well.

- They show that they have the right competencies to weigh the potential positive and negative effects of their decisions. Their mentality leads to ethical considerations, balanced decisions, and honest reconciliations of dilemmas.

While there’s an entire industry and ecosystem set up around risk management, how well do its conventional approaches help decision makers deal with uncertainty, disruption, and dilemmas? Or is it more of a belief system? Could there be missionaries, believers, and inquisitors who have serious commercial interests in maintaining the system? Understanding the current dominant view of risk management, how we got here, and the challenges it creates can help find a new perspective on dealing with uncertainty that could better support the goal of companies to stay future-proof.

SERIOUS ISSUES WITH CONVENTIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT

Many executives see risk management primarily as a compliance matter. To them, effective risk management means above all that they don’t get into trouble with their external or internal supervisors. Due to their role, oversight bodies are hardly interested in the “upside” of risk. It’s their duty to minimize the downside.

During training, board members are taught to ask about the top 10 risks. That’s apparently a sign that management has thought carefully about the company’s vulnerabilities and taken suitable actions to mitigate them.

Board members and supervisory authorities keep asking for risk profiles with remarkable tenacity, which indicates that risk management has become an accountability tool. That’s quite different from a tool for better achieving your goals under uncertainty.

Recent insights underscore the issues with conventional risk management. Roger Estall and Grant Purdy conclude in their book Deciding that risk management is a millstone hanging around the neck of organizations and should be abandoned.

First of all, what are we talking about when we use the word “risk”? There’s no universal definition. It’s striking that the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) uses more than 40 different definitions of risk in its own documents.

In both the 2013 Internal Control—Integrated Framework from the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) and COSO’s 2004 Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework, “risk” refers to something negative—something that can cost you money, that can be bad for your health, and that can discredit you. Since its inception in 2009, the ISO 31000 Risk Management—Guidelines used a neutral risk concept—as does COSO’s 2017 Enterprise Risk Management—Integrating with Strategy and Performance. In those documents, risk encompasses both positive and negative effects on the achievement of objectives.

These changes come with far-reaching consequences. Originally, COSO used four so-called risk responses: accept, avoid, reduce, and share. COSO added pursue—“accept increased risk to achieve improved performance”—as the fifth risk response in 2017. This is more in line with the common concept of balancing risk and return.

Because risk has very different meanings, simply using the term could lead to confusion. The conventional definition focuses on things that can go wrong. This is by no means holistic since decision making requires balancing pros and cons. For example, when you start investing, hopefully you aren’t only concerned with possible losses but also with returns. Alternatively, if you take risk’s definition to include both upside and downside risk, then you lose most people in your audience because of the negative connotation that risk has in common parlance.

Because of all this confusion, Norman Marks (normanmarks.wordpress.com) and others suggest avoiding the word “risk” entirely. Terms such as “uncertainty management,” “success management,” or “expectation management” might be better alternatives. I regularly use “value management.” After all, both COSO and ISO indicate that it’s about creating and protecting value. Value management also takes into consideration that different stakeholders value different things, such as safety, dividends, or punctuality. And the term appeals to people much more than “risk management.”

There’s no science called “riskology”—no dedicated field focused on the empirical study of risk. Rather, a self-contained risk management world has been created with all kinds of consultant-recommended paraphernalia. Those working methods must then be integrated into the existing management cycle.

One of the artifacts of conventional risk management is the risk appetite statement, which refers to the type and amount of risk a company is willing to accept. Yet how is the amount of risk expressed? There’s no unit of measure or currency for risk. Risk profiles suggest that you can add up risks for convenience purposes. Yet if you try to aggregate risks based on monetary value, you’ll soon discover that what you value most is difficult to monetize.

What we may not always realize is that opportunities and threats are our mental images of possible future events, changes in circumstances and trends. These images are strongly influenced by our personalities, knowledge, and experiences. Above all, as Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman points out, we humans are very susceptible to biases.

Many risk assessments are done qualitatively. Scores are awarded to estimated likelihoods and effects using values on ordinal scales (for example, from 1 to 5), much like the type of scales used in opinion polls or to rate the quality of hotels. Yet one can’t simply multiply ordinal values in order to come up with risk scores as an attempt to prioritize risks.

Risk quantification is highly dependent on the quality and quantity of the data and on the assumed parameters in the model. If the assumptions used are no longer valid, the value of the model expires. Moreover, they remain just models; a map isn’t the area that it represents.

Making decisions is never about a single objective. Exceptions include the one-sided “shareholder value” approach in which risks are mainly seen as threats to the earnings potential. We have all witnessed the derailments to which the approach “money as an end” instead of “money as a means” has led. In reality, decision makers are faced with dilemmas because there are always competing stakeholder interests.

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON RISK

In contrast to the conventional approach that advises implementing a separate system called “risk management” aimed at countering troubles, more recent insights suggest a focus on looking ahead in a consequence-conscious way when making decisions. This involves considering the potential effects of acting or refraining from action as part of your regular business responsibilities.

Decision makers have to weigh the pros and cons of their options. Rarely does anything in life come with benefits only. There are always potential or actual drawbacks too. Take, for example, acquiring a retail property. It doesn’t only come with advantages, such as potential capital accumulation, more freedom to adjust it to the company’s needs, and lower monthly costs than renting.

It’s essential to consider the possible disadvantages as well. In essence, if you need debt financing, you’re speculating with borrowed money. You may also end up in the unlucky circumstances of having to deal with subsiding foundations or a deteriorating neighborhood.

A management team won’t become successful by reducing failures. Periodically updating a list of things that could go wrong isn’t the same as figuring out how best to achieve the company’s goals. Success requires both seizing opportunities and limiting threats.

Making decisions is at the heart of management. It implies allocating scarce resources and limited people in order to deliver products and services that meet requirements and expectations. In his book Risk Management in Plain English: A Guide for Executives, Norman Marks emphasizes the importance of focusing on increasing the likelihood of your success. That involves weighing possible pros and cons when reconciling dilemmas.

Why would you first create a separate risk management system and then try to integrate it into your regular management system? Isn’t it much wiser to start from the position of the decision makers?

Making balanced decisions requires the willingness to factor in unwelcome information as well. When interpreting the information at hand, you need to be aware of your exposure to ingenious influencing and framing techniques. Parties will highlight the advantages and mask the disadvantages of an available option that serves their interests. That’s why it’s important to engage coaches who think constructively and critically, who question and challenge your choices, and who want to help you increase the probability of your success.

Do you really want to add value as a management accounting or finance professional? Provide decision support as a critical friend when assisting colleagues with preparing realistic plans, business cases, and forecasts.

THE VALUE OF THESE NEW INSIGHTS

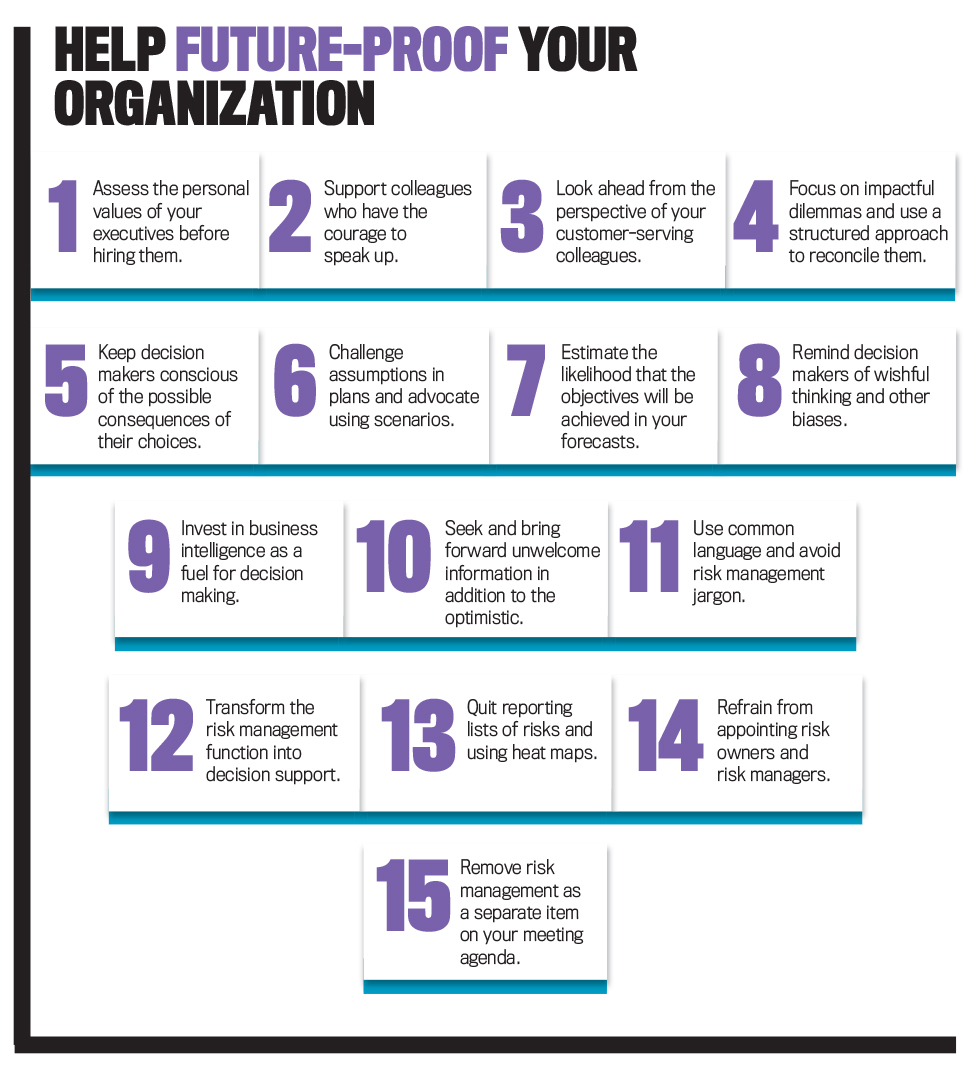

To stay future-proof, what executives really need to know is how likely it is that their plans and strategies are going to succeed. Therefore, as a management accounting and finance professional, assess the extent to which management team members ask what-can-happen and what-if-x questions, make their assumptions explicit, and show consequence consciousness.

Investigate how they deal with assumptions in proposals, budgets, business outlooks, and so on. Are their estimates realistic and balanced? Are the right experts involved? Is there room for critical voices? If decision makers choose an option because of the perceived advantages, are they also prepared to deal with the associated disadvantages?

Pay attention to the mentality of team members. Dilemmas are about ethical considerations. In practice, decision making is about dealing with competing interests, such as commerce vs. compliance. Imagine a prospect with all kinds of dubious business activities offering substantial earnings potential for your organization as a service provider. Which interests of which stakeholders do the executives give priority to?

Always discuss which objectives should be the priority. It’s a warning sign if only commercial interests predominate. This isn’t about what is formally stated on the website, but rather pay attention to the attitudes of executives and other decision makers. If avoiding getting caught is the main driver of compliance policies and practices, it tells you a lot about the company’s core values.

Stop maintaining risk inventories for the sake of identifying risks. Quit updating risk registers every year or quarter. Don’t spend endless time assessing risk levels. Risk management isn’t about updating risk lists. It’s about the likelihood of your success as an organizational unit, function, or project.

Don’t think about how the quality of risk appetite statements can be improved. Focus on how decision makers can be supported to make better decisions. What information do they need to be able to consciously weigh the pros and cons when making important choices such as product introductions, takeovers, or outsourcing?

Finally, realize that there’s reason for humility. Our human abilities to predict the future are seriously limited. It’s never possible to imagine in advance what could happen in a world with so many actors and factors. Instead, you need people who are alert to what’s going on, who welcome unpleasant news, and who are able to improvise.

April 2023