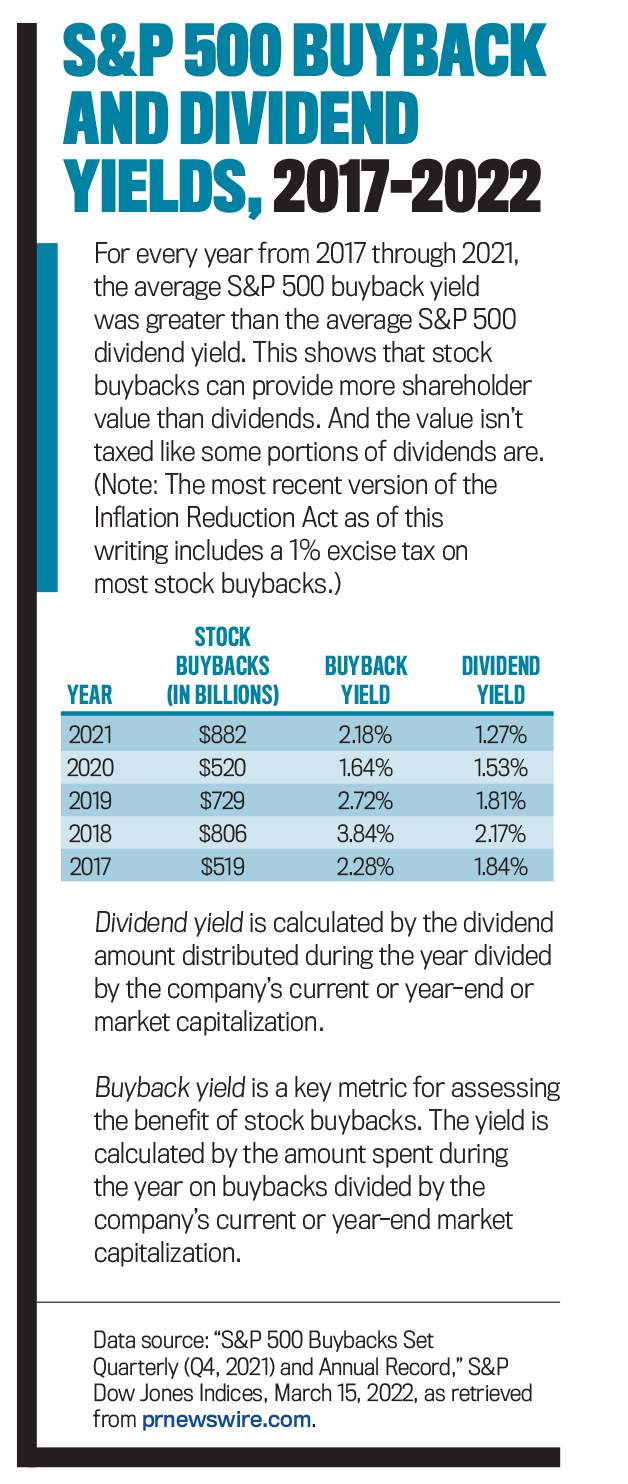

Companies continue to utilize stock buybacks as a tool to influence corporate financial conditions. According to Reuters, S&P 500 corporate common stock buybacks in the past few years have exceeded $500 billion annually. Initially considered a positive financial tactic, long-term use of stock buybacks (also known as stock repurchases) has caused some companies to slip into negative stockholders’ equity, which can bring a variety of financial difficulties. In recent years, companies including Boeing, Starbucks, The Home Depot, and McDonald’s have crossed a tipping point into negative stockholders’ equity as the result of many years of stock buybacks.

The continued use of this tactic has both positive and negative features. We propose a strategy for reversing the damage from negative stockholders’ equity as well as a work-around metric to replace return on equity (ROE) when it ceases to generate a meaningful measurement of management effectiveness. With this guidance, finance professionals should be better equipped to anticipate and plan countermeasures to the possible negative effects of long-term use of stock buybacks.

PURPOSES OF STOCK BUYBACKS

Stock buybacks enhance shareholder value by reducing the number of shares outstanding. Consequently, earnings per share (EPS) rises and stock price will tend to increase too. If carefully planned, the buybacks should occur when stock prices are “undervalued” to make the committed buyback funds stretch further.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

In the United States, the current rules from the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) require companies to announce their buyback plan beforehand with either the approximate dollar amount committed or the maximum number of shares to be purchased. Buybacks must be announced and reported on any of SEC Forms 8-K, 10-Q, or 10-K to avoid insider trading risks as well as to adequately inform both shareholders and the public. Due to institutional delays in communicating buyback information, investors typically discover when transactions occurred weeks or months after they occur.

Over the past 10 years, companies have increasingly adopted stock buybacks as a tool to accomplish multiple financial objectives. One major goal is counterbalancing the dilutive effects of executive stock option exercises. Stock option compensation plans provide incentives for company executives to personally buy common shares at a discounted rate. The executives benefit when a targeted stock price is achieved as a trigger for qualifying for stock options. When these stock options are acquired and exercised, the issuances of additional shares produce a dilutive effect on the company’s EPS. Corporate stock buybacks tend to offset the dilution by reducing the overall number of shares outstanding. In the absence of any significant executive stock options exercised, buying back shares will cause EPS to rise somewhat.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Another major rationale for a buyback is to increase EPS, which benefits shareholders and executives. Beyond the positive effects on stock price to shareholders, executives can also benefit from increases to EPS, free cash flow per share, and return on assets (ROA), all of which will tend to increase the market value of common stocks and thereby enhance the executives’ potential to qualify for even more future stock options.

POTENTIAL NEGATIVE IMPACTS

Despite the positive effects for building stockholder wealth, long-term use of stock buybacks can produce negative effects on the balance sheet and important financial ratios. Two potential downsides include tipping into negative stockholders’ equity and distorting the ROE leading up to and following the tipping point.

Both of these situations can be traced to the same root cause: Buyback stock prices are virtually always significantly higher than the original average issue prices of common stock. This buyback “price gap” means that each share purchased will require more funds than the amount of contributed capital originally collected when the stock was issued. Consequently, buybacks exert downward pressure on total stockholders’ equity and book value per share while increasing the possibility of technical insolvency.

A sign that a tipping point might be approaching is a dramatic increase in ROE. The long-term ROE for S&P 500 companies is approximately 14%. Normally, it’s a good metric to evaluate the effectiveness of senior management’s ability to generate a return on the capital provided by owners. In the later stages of a declining stockholders’ equity balance, however, ROE gets artificially inflated as a mathematical artifact of the decline. In the years prior to reaching the tipping point, companies experience increasingly inflated ROE.

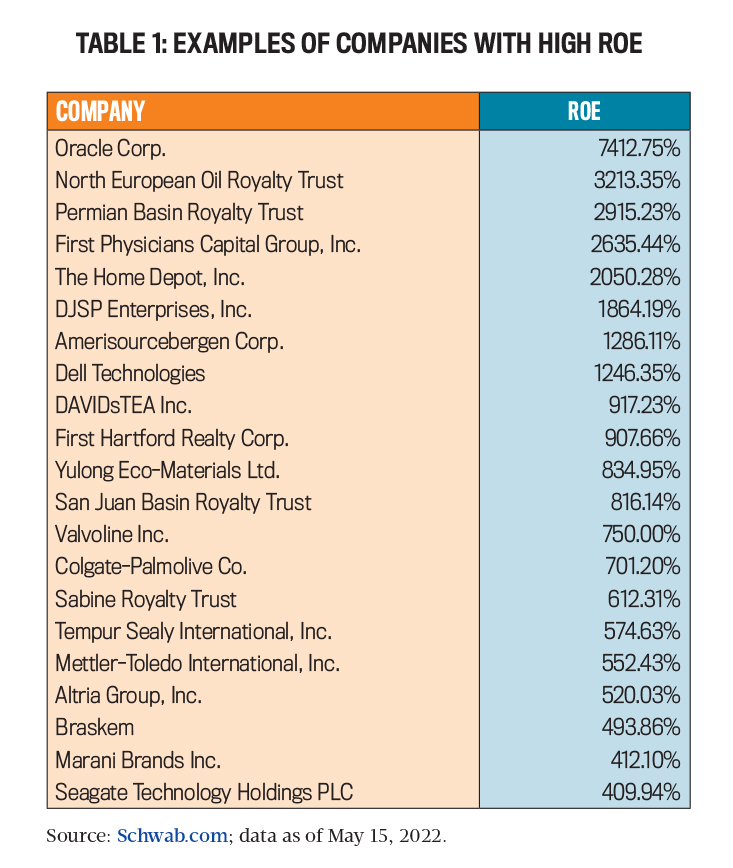

Based on our examination of historic data, if a company has been using stock buybacks for at least three to four years and the ROE exceeds 70%, it may signal a possible dip into negative stockholders’ equity in upcoming years. Table 1 provides a partial list of companies with ROE higher than 100% as of May 15, 2022. We believe these companies are at risk for tipping into negative stockholders’ equity in years to come.

THE CASE OF HOME DEPOT

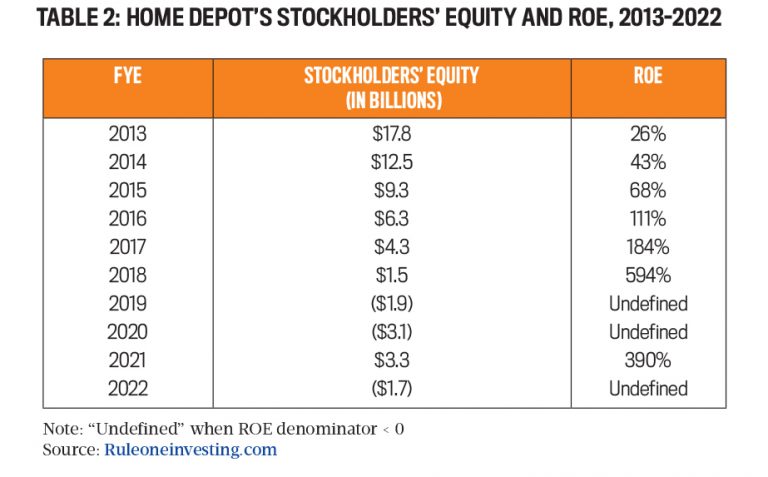

A good example of this is Home Depot, a company that had achieved positive profitability for more than 30 years. The tipping alert came in 2017 and 2018 when its ROE started climbing at an accelerated rate, rising to triple-digit percentages. Then Home Depot’s ROE became mathematically “undefined” in 2019 and 2020 due to negative stockholders’ equity. In response, the company stopped buybacks for a few quarters. Combined with a strong profit year, the result was that its stockholders’ equity returned to positive.

Table 2 shows the trends in Home Depot’s stockholders’ equity and ROE from 2013 to 2022. Stockholders’ equity began at $17.8 billion in 2013, declined to $1.5 billion in 2018, and fell into negative territory in 2019. Notice how ROE became inflated, rising from 26% in 2013 to 594% in 2018. Then it became mathematically undefined (due to a denominator < 0) in three of the following four years. This shows how the balance sheet can deteriorate due to stock buybacks.

Not all companies will inevitably fall into this pattern. The factors leading to such circumstances include (1) a large difference between common stock issue prices and buyback prices, (2) sustained pursuit of stock buybacks over a period of years, and (3) use of the retirement method for recording purchases.

According to Robert Honeywill, the number of technically insolvent companies in the S&P 500 more than tripled between 2015 and 2020, primarily due to share buybacks funded with corporate debt. Buybacks are recorded by reducing stockholders’ equity. This causes an increase in the debt-to-equity ratio, meaning that the company is funded more by debt. In addition, companies may choose to fund buybacks by increasing long-term debt.

Click to enlarge.

Negative stockholders’ equity is considered as “technical insolvency” even though the company may not have any real problem in its debt service. (See Table 3 for a partial list of S&P 500 companies that have tipped into negative stockholders’ equity.)

Click to enlarge.

Negative stockholders’ equity is considered as “technical insolvency” even though the company may not have any real problem in its debt service. (See Table 3 for a partial list of S&P 500 companies that have tipped into negative stockholders’ equity.)

There are a number of possible downside effects of negative stockholders’ equity. Since negative stockholders’ equity means a company has more debts than assets, it could make it difficult to get additional loans approved and/or result in higher interest rates. Credit ratings might also suffer—though this didn’t happen with Home Depot because it continues to generate positive cash flow from operations along with consistently making debt payments.

If buybacks drive a company into negative retained earnings, the choice to declare cash dividends evaporates. Customer relations also might suffer due to concerns about the viability of continued operations. Finally, with the loss of ROE as a tool to evaluate management effectiveness, some existing or potential stockholders might back away from the investing table. (It’s worth noting that although investors tend to use ROE to evaluate performance of top management, other financial metrics are available that, when combined, may offer a more complete perspective of enterprise performance.)

ACCOUNTING FOR STOCK BUYBACKS

To understand how to reverse the unintended negative impacts of stock buybacks, it’s important to first review the methods for recording stock repurchases under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Companies generally choose either the retirement method or the cost method to record stock buybacks. (A third recording method—the par value method—is also permitted by GAAP but is rarely used, so we don’t discuss it here.) Only the cost method offers a possible path for reversing negative stockholders’ equity.

Retirement method. Under the retirement method, the repurchased shares are essentially destroyed without any intention to resell them in the future. Companies that choose this method might be signaling to the investing marketplace that either (1) the common stock price is undervalued and/or (2) they want to permanently shrink the number of common shares outstanding as a long-term strategy.

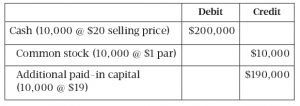

In the retirement method, stockholders’ equity is recorded by the following transaction rules:- The common stock account is debited by the number of shares repurchased multiplied by the par or stated value per share.

- Additional paid-in capital is debited by the number of shares repurchased multiplied by the average per share of any additional paid-in capital from the original stock issuance.

- Retained earnings is debited by any remaining amount needed to finalize equal debits and credits.

- Cash will be credited as an outflow to acquire the shares.

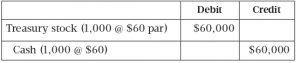

Assume that this year the company buys back 1,000 shares at $60 per share. Under the retirement method, the journal entry will be:

Buyback entry using retirement method

Assume that this year the company buys back 1,000 shares at $60 per share. Under the retirement method, the journal entry will be:

Buyback entry using retirement method

Notice that the common stock and additional paid-in capital accounts are reduced pro rata according to the average per-share amounts that were recorded in the original issuance journal entries. In virtually all stock buybacks, the buyback price is significantly higher than the issue price. The GAAP treatment under the retirement method is to charge any excess amount to retained earnings. If a company continues to buy back shares over many years, it could exhaust any positive balance in retained earnings. Even with positive profits each year, the buyback effects could be larger than the positive effects of net income that might increase retained earnings as year-end closing entries. Eventually, the total of the stockholders’ equity section could become negative.

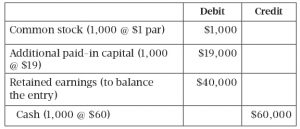

Cost method. Companies that choose the cost method will create a treasury stock contra-account within stockholders’ equity. This indicates to the marketplace that the company is likely to resell the shares at a higher price in the future and thereby dilute EPS.

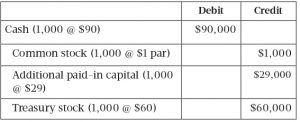

With the cost (or treasury stock) method, the entire amount of the cash paid to repurchase shares in our example is charged to the treasury stock account. Treasury stock is shown at the bottom of the stockholders’ equity section of the balance sheet as a deduction on the last line before the section total.

Taking the same information for the example of XYZ Company, the buyback using the cost method is: Buyback entry using the cost method As a stockholders’ equity contra-account, treasury stock has a normal debit balance and should be shown at the bottom of the stockholders’ equity section as a negative number before total stockholders’ equity. In our example, it would appear as:

Less: Treasury stock (at cost, 1,000 shares) $60,000

As a stockholders’ equity contra-account, treasury stock has a normal debit balance and should be shown at the bottom of the stockholders’ equity section as a negative number before total stockholders’ equity. In our example, it would appear as:

Less: Treasury stock (at cost, 1,000 shares) $60,000

Over many years of stock buybacks recorded using the cost method, stockholders’ equity could tip into negative territory, but a large treasury stock account balance can be reversed by simply reselling shares. This provides an opportunity to reverse negative stockholders’ equity by reselling the shares.

Technically, treasury shares have been issued, but they aren’t outstanding. When they’re sold again hopefully at a higher price, it creates a nontaxable event for the corporation. The proceeds of the transaction produce an inflow of cash as it erases the treasury stock according to the number of shares repurchased. The number of shares outstanding does increase with resale, but the boost in cash may offset the dilution somewhat by boosting assets.

Let’s assume the 1,000 treasury shares are held for two years and then resold at $90 per share. The transaction would be recorded as: Resale of treasury stock at a higher price than buyback price

Notice that there’s no gain on this transaction even though the 1,000 shares were sold for $30 per share more than the buyback price. Both GAAP and U.S. federal tax laws are consistent on this issue that “gains” on the sale of a company’s own treasury shares aren’t recognized.

Apple Inc. has been buying back shares since 2012 using the retirement method. From 2012 to 2017, Apple’s ROE was mostly in the 30%-40% range. As of May 2022, Apple’s ROE (trailing 12 months) was reported at 150%, signaling an alert to a possible tipping point sometime in the next few years if the company continues repurchasing common shares. Apple’s stockholders’ equity has declined to approximately 50% of its 2017 level.

Click to enlarge.

Home Depot continues to use the cash method. Therefore, it could resell shares to move back to a more positive stockholders’ equity balance. Apple doesn’t have this choice.

Click to enlarge.

Home Depot continues to use the cash method. Therefore, it could resell shares to move back to a more positive stockholders’ equity balance. Apple doesn’t have this choice.

OPERATING INCOME ROA

Buybacks can destroy ROE as a metric to evaluate management effectiveness. If ROE is mathematically undefined, then operating income ROA (OROA) is a good substitute. Although ROA is normally calculated as net income divided by average total assets, we recommend using a revised formula for ROA, which is calculated as operating income divided by average total assets. Operating income represents a more controllable layer of profitability compared to net income.

Operating income excludes the effects of taxes, interest expense, and nonrecurring gains and losses on the sale of business units. Tax and interest expenses come from long-term business strategies that have been in place for many years. Nonrecurring gains and losses may not be the responsibility of the day-to-day managers of the business.

ANTICIPATING THE FULL IMPACT

The long-term use of stock buybacks can lead to negative stockholders’ equity and thereby also negative book value. Both unusual balance sheet artifacts may open the door to financial difficulties such as reduction of credit ratings, higher interest rates, loss of customer confidence, and concerns from potential investors.

The following takeaways should be helpful to finance teams:- If ROE rises above 70% during a period of at least three to four years of stock buybacks, this could signal possible slippage into negative stockholders’ equity.

- Consider using the cost method for recording stock Instead of retiring purchased shares, hold them in treasury stock, thus leaving open the possibility for reversing negative stockholders’ equity.

- When ROE becomes artificially inflated or mathematically undefined, use OROA as the tool to evaluate management effectiveness.

- Ensure consistently positive operating cash flow to help offset the potential impact of negative stockholders’ equity on corporate credit ratings.

Looking ahead, the SEC is expected to continue to find ways to facilitate flows of information about stock buybacks. Some of the potential changes this might lead to include: (1) shortening the current delays in reporting stock buyback information to investors, (2) enhancing the disclosure of more buyback information, and (3) restricting executives and directors from selling or purchasing stock within a specified number of days before or after the announcement of a buyback plan.

With this guidance, corporate finance teams should be in a better position to anticipate the full impact of stock buybacks and to plan countermeasures if needed to avert financial difficulties.

September 2022