NEW REVENUE RECOGNITION GUIDANCE

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued ASC 606 in 2014 (Accounting Standards Update 2014-09) as part of its joint project with the International Accounting Standards Board to clarify the principles for recognizing revenue and to develop a common revenue standard for U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles and International Financial Reporting Standards.

In an acknowledgment of the primary role that revenue recognition plays in an entity’s financial performance, as well as the significant changes brought about by the new guidance, organizations were given several years before they would be required to report their results under the new standard. The initial implementation window of ASC 606 was staggered based on company characteristics (e.g., public vs. private). But in recognizing the significance of these rule changes, as well as the disruptions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, the FASB extended the implementation deadline for many companies by another year in 2020.

Given the importance of the new rules, along with their relatively recent adoption by many companies, the proper implementation of ASC 606 remains a highly relevant topic—especially in light of the increased employee dislocation and turnover caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The FASB states that “the core principle of [the guidance] is that an entity should recognize revenue to depict the transfer of promised goods or services to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for those goods or services.” To achieve that core principle, the FASB provides a five-step model:

Step 1: Identify the contract(s) with a customer.

Step 2: Identify the performance obligations in the contract.

Step 3: Determine the transaction price.

Step 4: Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in the contract.

Step 5: Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation.

APPLYING THE GUIDANCE TO LONG-TERM CONTRACTS

ASC 606 supersedes the guidance for long-term contracts provided by ASC 605. Under the old guidance, companies often had the option of accounting for long-term contracts through either the completed contract method or the percentage-of-completion method (the recommended method when reliable estimates were possible). The main conceptual changes that the new guidance in ASC 606 prescribes for long-term contracts are (1) the requirements to divide a contract into separate performance obligations, assigning a transaction price to each, and (2) determining when the customer has control of the contracted good or service. These key changes can translate to dramatic differences in the timing of revenue, expense, and profit recognition for long-term contracts.

Regarding performance obligation transaction prices, the FASB states that an entity should allocate the transaction price to each performance obligation based upon its observed or estimated stand-alone selling price at contract inception. On the issue of control, an entity should recognize revenue when (or as) it satisfies a performance obligation by transferring a promised good or service to a customer. A good or service is transferred when (or as) the customer obtains control of that good or service. ASC 606 states that an entity transfers control of a good or service over time and, therefore, satisfies a performance obligation and recognizes revenue over time if at least one of the following criteria is met:

- The customer simultaneously receives and consumes the benefits provided by the entity’s performance as the entity performs.

- The entity’s performance creates or enhances an asset (for example, work in process) that the customer controls as the asset is created or enhanced.

- The entity’s performance doesn’t create an asset with an alternative use to the entity, and the entity has an enforceable right to payment for performance completed to date.

COMPARING OLD GUIDANCE TO NEW

In the following hypothetical example, we demonstrate the accounting techniques for a long-term contract under both the old (ASC 605) and new (ASC 606) revenue guidance. In doing so, we highlight key differences between the old and new standards as well as the inherent managerial discretion that now exists in revenue and expense recognition timing based on the structure of a specific long-term contract.

For this example, assume a contractor has signed a long-term contract with a customer. The estimated duration of the contract is three years. The estimated total contractor cost from the contract is $600,000. And the total contractor revenue from the contract is $1.2 million. As revenue is typically recognized when work is both completed and billed to the customer, we assume that all appropriate customer billing is made without delay. The following scenarios illustrate the procedures for revenue recognition under ASC 605 and ASC 606.

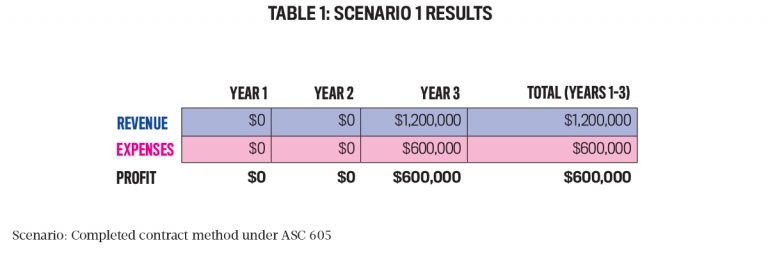

Scenario 1: Use of completed contract method (ASC 605). Under ASC 605, contractors could choose to use the completed contract method in certain instances. In doing so, the contractor wouldn’t need to establish who was the controlling party of the good or service during the contract period. Neither would the contractor need to separate the contract into individual performance obligations (which is the case under ASC 606). It would simply defer the recognition of all revenue and expense until the entire contract was completed. Thus, the total contract revenue of $1.2 million and total expense of $600,000 would both be recognized upon contract completion in Year 3 (see Table 1).

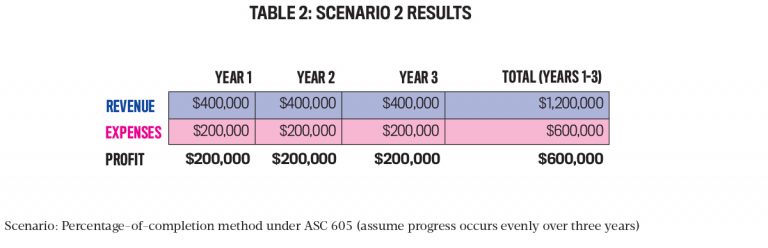

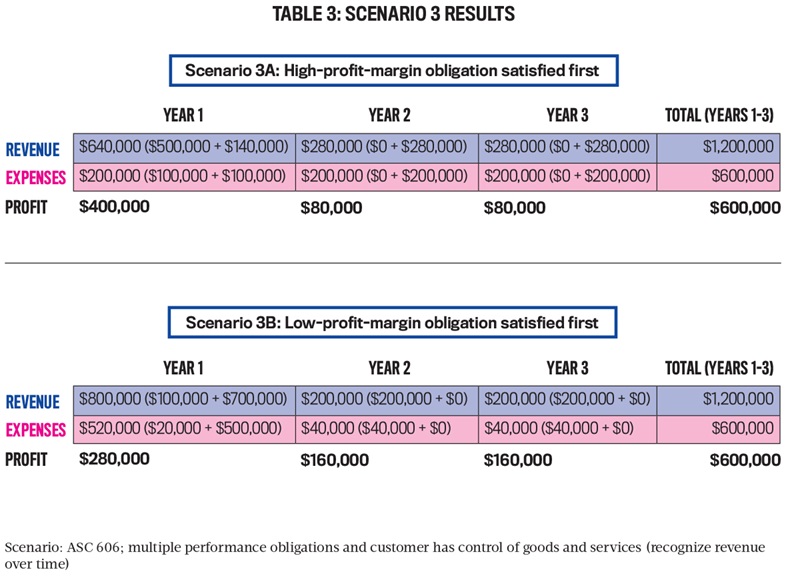

Scenario 2: Use of percentage-of-completion method (ASC 605). Under Topic 605, contractors commonly used the percentage-of-completion method. In doing so, the contractor wouldn’t need to establish who was the controlling party of the good or service during the contract period. Neither would it need to separate the contract into individual performance obligations. It would recognize expense periodically as contract work was completed and could measure progress using either an input method (e.g., costs incurred) or output method (e.g., units of delivery). In our example, for simplicity, assume that progress occurs evenly over the three years of the contract. Thus, as shown in Table 2, revenue per year equals $400,000 ($1.2 million contract value divided by three years), and the expense per year equals $200,000 ($600,000 contract cost divided by three years). Scenario 3: Identification of multiple performance obligations, recognizing revenue over time due to a customer having control of contract goods and services for the duration of the contract (ASC 606). Under ASC 606, the contractor must determine which party has control over the contract goods and services during the contract period. In addition, it must separate the contract into individual performance obligations and assign a transaction price to each based on observed or estimated stand-alone sales price. For this scenario, assume that the customer has control for the duration of the contract. Thus, based on the FASB criteria, the contractor would recognize revenue over time (as opposed to a point in time when control is eventually transferred). In assigning transaction prices (and costs) to separate performance obligations, unequal profit margins on the separate obligations could mean that more or less revenue might be recognized relative to cost depending on which obligation was being satisfied. In this case, the timing of revenue recognition on the overall contract wouldn’t simply mirror that of the percentage-of-completion method under the old guidance. For example, using the percentage-of-completion method, 40% of the total contract cost incurred would normally mean 40% of the revenue recognized. Under Topic 606, however, when high-margin performance obligations are completed first, 40% of total contract cost being incurred may correspond to much more than 40% of total contract revenue being recognized. (Note the inherent managerial discretion that exists in structuring long-term contracts at the outset when discussing the subsequent revenue and expense recognition from these contracts.) For this scenario, assume that the overall contract consists of two performance obligations:

- Obligation 1 (high-profit-margin) has a transaction price of $500,000 and $100,000 in cost.

- Obligation 2 (low-profit-margin) has a transaction price of $700,000 and $500,000 in cost.

Since the obligations have unequal profit margins, the amount of revenue recognized will be different based on which obligation is getting satisfied as costs are incurred.

For Scenario 3, we present two situations (see Table 3): Scenario 3A: High-profit-margin obligation satisfied first. Assume that Obligation 1 (the high-profit-margin obligation) is satisfied by the end of Year 1 and Obligation 2 (low-profit-margin obligation) is satisfied over three years as follows: 20% in Year 1, 40% in Year 2, and 40% in Year 3.

The recorded expense per year in this scenario is the same as Scenario 2’s percentage-of-completion method under ASC 605. In this scenario, however, both revenue and profit recognition are accelerated relative to the percentage-of-completion method because (1) the high-profit-margin obligation was satisfied more quickly than was the low-profit-margin obligation, and (2) revenue was recognized over time, as opposed to a point in time, due to the customer having control.

Scenario 3B: Low-profit-margin obligation satisfied first. In this situation, assume that Obligation 2 (low-profit-margin obligation) is satisfied by the end of Year 1 and Obligation 1 (high-profit-margin obligation) is satisfied over three years as follows: 20% in Year 1, 40% in Year 2, and 40% in Year 3.

This situation shows delayed profit recognition compared to Scenario 3A even though the low-profit-margin work is being performed more quickly than the high-profit-margin work is. The result is greatly accelerated expense recognition overshadowing mild accelerated revenue recognition and, consequently, delayed profit recognition.

Scenario 4: Identification of multiple performance obligations and recognizing revenue at a point in time due to contractor having control of goods and services for the duration of each performance obligation (ASC 606). For this scenario, assume that the overall contract consists of the same two performance obligations (with the same transaction prices and costs) in Scenario 3. The difference in this scenario is that we assume that the contractor has control of the goods and services for each performance obligation until that obligation is satisfied. At that point, control would transfer to the customer, and the contractor would recognize the revenue for the satisfied obligation. We present two situations for this scenario as well (see Table 4):

Scenario 4A: High-profit-margin obligation satisfied first. Assume that Obligation 1 (high-profit-margin obligation) is satisfied by the end of Year 1 and Obligation 2 (low-profit-margin obligation) is satisfied over three years as follows: 20% in Year 1, 40% in Year 2, and 40% in Year 3.

This situation shows accelerated revenue and profit recognition compared to Scenario 2’s percentage-of-completion method under ASC 605. This is due to the high-profit-margin obligation being completed before the low-profit-margin obligation. Yet this situation shows delayed revenue and profit recognition compared to Scenario 3A. Because the contractor has control in this scenario, revenue recognition occurs only upon completion of the performance obligation instead of over time as in Scenario 3A.

Scenario 4B: Low-profit-margin obligation satisfied first. Assume that Obligation 2 (low-profit-margin obligation) is satisfied by the end of Year 1 and Obligation 1 is satisfied over three years as follows: 20% in Year 1, 40% in Year 2, and 40% in Year 3.

Scenario 4B shows delayed profit recognition compared to Scenario 4A. The contractor has control in both situations, but 4B shows the low-profit-margin work being performed more quickly than the high-profit-margin work. The result is a greatly accelerated expense recognition overshadowing mild accelerated revenue recognition and, consequently, delayed profit recognition.

Figure 1 presents the potentially dramatic differences in reported income across time periods described in the different scenarios and situations. All of this indicates that under ASC 606, all else being equal, higher-margin work being determined to have been performed first will result in accelerated income recognition relative to the traditional percentage-of-completion method, while lower-margin work being determined to have been performed first will result in delayed income recognition.

BENEFITS AND RISKS OF ASC 606

Under the new revenue recognition guidance, managers now have more discretion with respect to revenue and cost recognition across time periods than when using the traditional percentage-of-completion or completed contract methods. This stems from their need to now determine the separate performance obligations within the overall contract, the revenue and costs allocated to each, and any discretion they may have in the sequence that the obligations are determined to be satisfied. As is often the case with accrual accounting, this additional managerial discretion could enable managers to produce more accurate and nuanced financial reports relative to those under ASC 605; at the same time, it could theoretically be exploited by managers to more easily engage in earnings management or manipulation. Opportunistic managers could achieve such objectives through the initial structure of the contract and creation of specific performance obligations as well as through the obligation revenue and cost estimates and the sequence that they’re determined to be satisfied.

Due to the additional managerial discretion and nuance inherent in ASC 606, along with the central role that revenue recognition plays in reported financial performance, we believe both financial statement preparers and users benefit from a clear understanding of these significant rule changes. For managers, additional contract documentation and analysis may be warranted, especially as it relates to potential complexities surrounding, for example, the process of determining distinct performance obligations and their transaction prices.

The question of when customer acceptance or control has occurred can also require careful judgment. For their role in assessing managerial estimates, ASC 606 may justify additional documentation and analysis for auditors—who should be mindful of the potential threat to their independence in the event they become too involved in the client’s implementation of ASC 606. We believe that the relatively recent implementation of ASC 606, coupled with the unusual economic conditions of the last couple of years, mean these new revenue recognition standards are worthy of continued focus. It may still be too early to fully identify the significant changes being brought about by their implementation.

September 2022