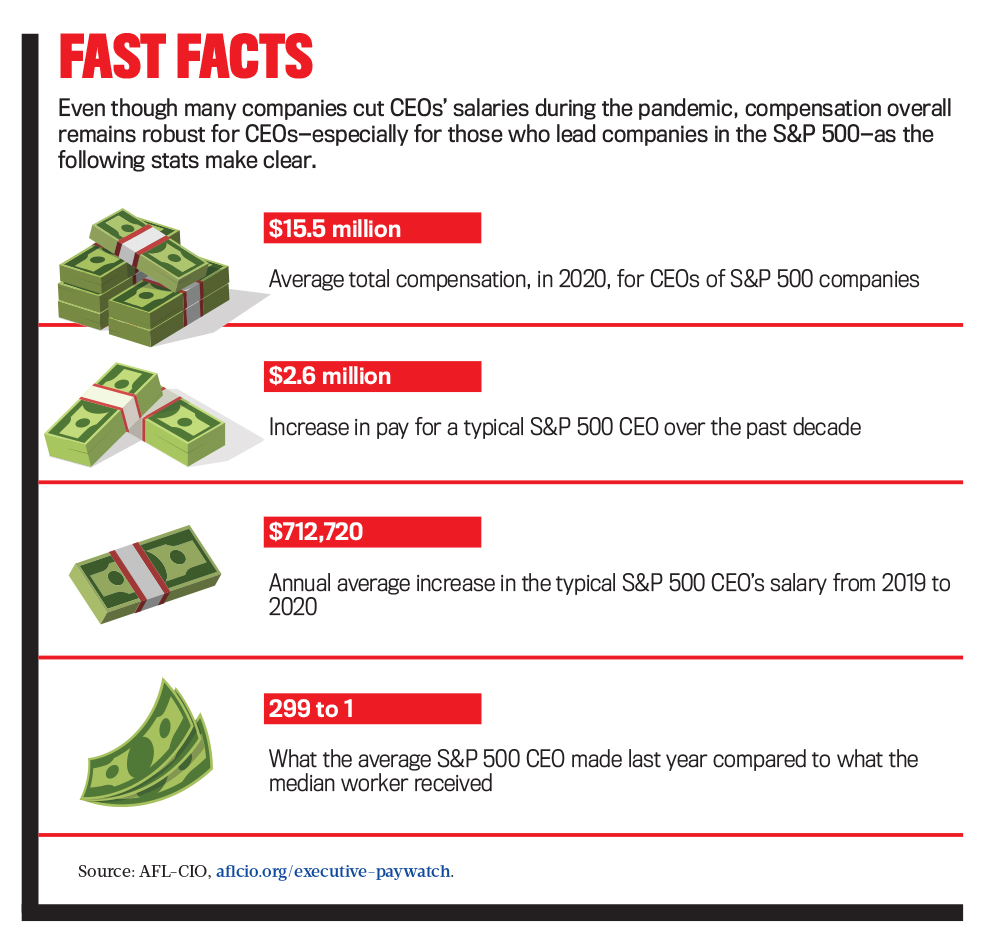

STUDY DESIGN

Even before March 11, 2020, when the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, some affected companies instituted significant changes, including cutting CEO pay. For example, on March 10, United Airlines announced that in addition to reducing its flight schedules, its CEO and president weren’t taking any salary for the next few months. In this case and others, the decision to cut CEO pay may reflect a response to poor performance and the need to conserve cash in an effort to survive the economic downturn, but it may also have been a signal that the company was sensitive to the plight of its workers and shareholders, with both groups adversely affected by shutdowns. In some cases, curtailing CEO compensation also generated positive public reactions.

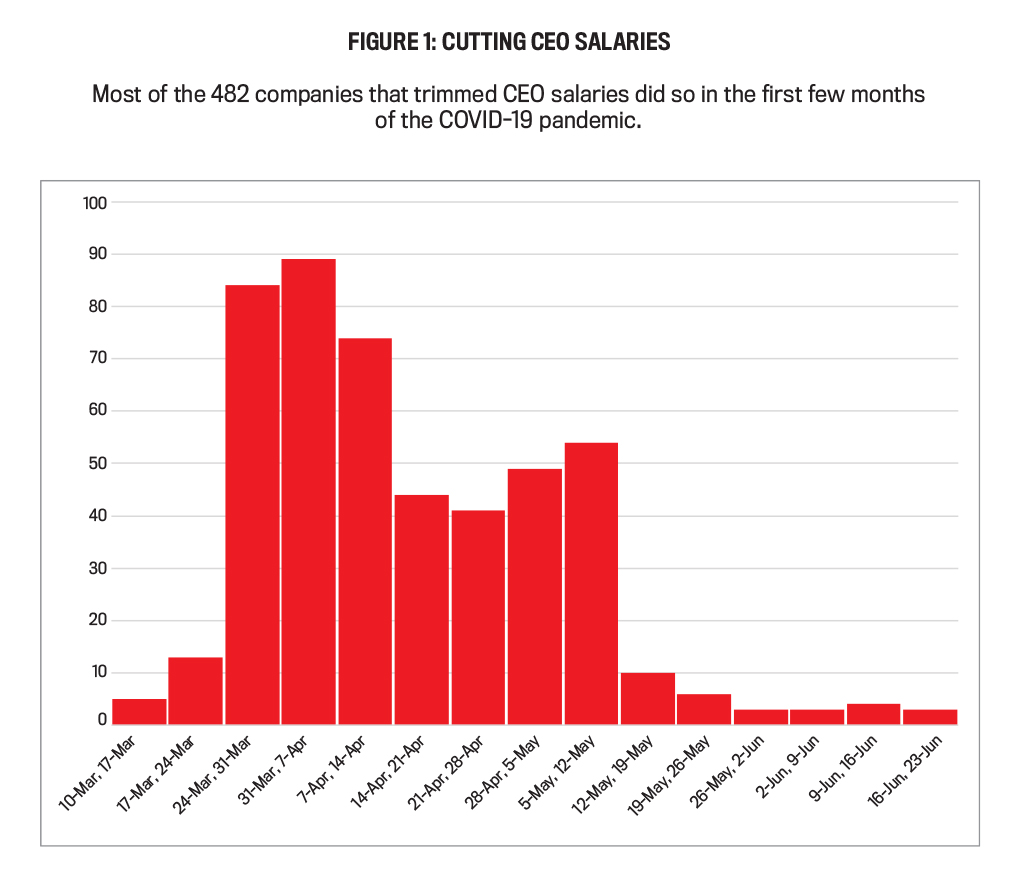

For our study, we identified a sample of 482 companies that announced CEO salary cuts from searches of U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) filings between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2020. Companies announced pay cuts through press releases, which were captured in Form 8-Ks, while some also disclosed pay cuts in Form 10-Q filings. Figure 1 shows the CEO salary cut announcements by week for our sample of 482 companies. As you can see, the vast majority of pay cuts were announced at the start of the pandemic, between late March and early May 2020.

In our analyses, we compared these 482 companies with two other groups of companies that didn’t announce CEO pay cuts. The first is a large sample of 3,714 publicly traded companies with assets greater than $1 million and with a stock price greater than $1 per share. The other group is a subset of 1,307 of these companies, for which we were able to obtain information about the group of peers against which they benchmarked their CEO compensation.

ECONOMIC FACTORS

Our study included two variables to capture current company performance: (1) cumulative abnormal stock returns (CAR) over the one-month period prior to the announcement of a pay cut and (2) return on assets (ROA) for the fiscal year prior to the announcement of a pay cut. For companies that didn’t reduce CEO pay, these variables were measured over one month after the declaration of the pandemic and for the fiscal year prior to the pandemic, respectively. To consider the need to preserve cash, we considered companies’ cash levels at the start of the pandemic.

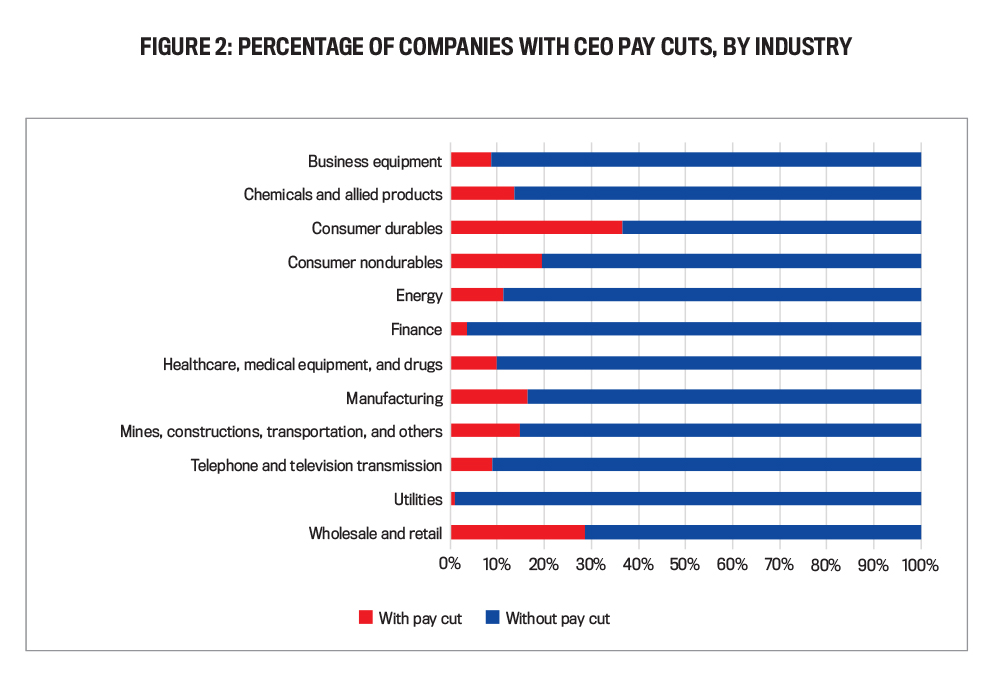

In addition, some organizations may have been motivated to cut pay to avoid negative scrutiny of executive compensation at a time when employees were being furloughed and laid off. We considered two variables to capture this: company size, which we measured as total sales, and the CEO pay ratio. Companies report pay ratio annually in the proxy statement. As compensation decisions are the purview of the board of directors, we considered board governance structures as another element of companies’ decisions to cut pay. We measured the proportion of the board composed of independent directors, the proportion of female directors on the board, and whether the CEO also holds the title of chairperson of the board. Outside directors are thought to bring more experience and advice to boards, while greater diversity in the boardroom may bring about better oversight and monitoring as well as better deliberations and decision making. CEOs who also serve as board chairs are considered more internally powerful and may prevent any salary cuts that were proposed. Finally, we considered an organization’s environmental, social, and governance (ESG) score. Companies that engage in more socially responsible activities may be more aware of employee labor practices and may be more inclined to cut CEO pay when employees are facing potential furloughs and layoffs. Examining these factors only, we found that poor stock price performance was a major driver of companies’ decisions to announce CEO pay cuts. We also found that these announcements were more likely in companies with lower cash reserves. These results confirmed our theory that economic uncertainty was an important factor in decisions to cut CEO pay. Consistent with our expectation that perceptions also matter, we found that larger companies and those with higher CEO pay ratios were more likely to announce pay cuts. (But when we consider both the size of the company, i.e., larger vs. smaller, and the company’s pay ratio in the regression analyses, only the pay ratio remains significant. This is likely because larger companies pay their CEOs more and thus have higher pay ratios—that is, pay ratio and company size are related.) Importantly, we controlled for industry membership (i.e., the industry the company operates in), so these economic factors are in addition to any effect that being in a particular industry—retail, for example—had on the decision to cut pay. (Figure 2 shows the percentage of companies that cut CEO pay, by industry.) When we examined the governance factors in a smaller sample for which we could obtain this information, we found no evidence that board structure or attentiveness to ESG issues affected the decision to cut CEO pay.

PEER PRESSURE

In our next set of tests, we analyzed the effect that peer pressure had on the pay-cut decision. Although we know that the focal company (or, simply, the company of interest) and peer compensation levels are correlated, it isn’t well understood how peer practices cascade through the peer group. A limitation with prior research is that compensation is reported annually in the proxy statement, which means that intrayear changes can’t be observed. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, provides an opportunity to examine how companies mimic their peers’ pay practices. First, because of the scrutiny that CEO compensation was getting during this time (as reflected in the higher rates of negative say-on-pay votes in shareholder meetings), companies may have been under greater pressure to conform to what their peers were doing when it came to reducing CEO salaries. In short, organizations likely didn’t want to appear to be outliers when their peers were cutting pay. The pandemic also allowed us to observe how pay practices cascaded from leaders to followers, because companies were reporting, in real time, changes in CEO compensation. The sequential timing of these announcements gave us visibility into pay practices that we couldn’t learn from annual proxy statements. Why is this useful? Focal companies may make compensation decisions similar to those of peer organizations because they’re similar on some factors that affect decisions about pay, so the similarity is an association but not a causal relationship. As an example, suppose both focal (Airline A) and peer (Airline B) companies suffer financial consequences and cut pay as a result of the drop in travel due to the pandemic. Airline A isn’t cutting pay because Airline B did; they’re both cutting pay because demand has been decimated. Alternatively, focal companies may make compensation decisions similar to those of peer companies because of the decisions made by those peers. By examining the timing of the decision to cut pay during the pandemic (measured as a company’s announcement that it will do so) and the degree to which other peer companies have already announced they’ve cut pay (the tipping point), we were able to provide first evidence on compensation leaders and compensation followers. We found that focal companies were more likely to cut pay if more of their peer companies did the same. Moreover, they were more likely to cut pay if the first company in their peer group did so early in the pandemic. Importantly, we controlled for the influence that economic characteristics, including industry membership, have on the decision to cut pay. This suggests that peer pressure is a unique force on compensation changes. What’s also interesting about this result is that it suggests that peer effects are symmetric in that companies will cut pay when peers do the same. The use of peer groups to benchmark pay has been criticized as a way of ratcheting up CEO compensation, sometimes likened to the “Lake Wobegon effect,” which relates to a tendency to overestimate one’s skills or competence. Our evidence, however, suggests that peers can place downward pressure as well.IS IT WINDOW DRESSING?

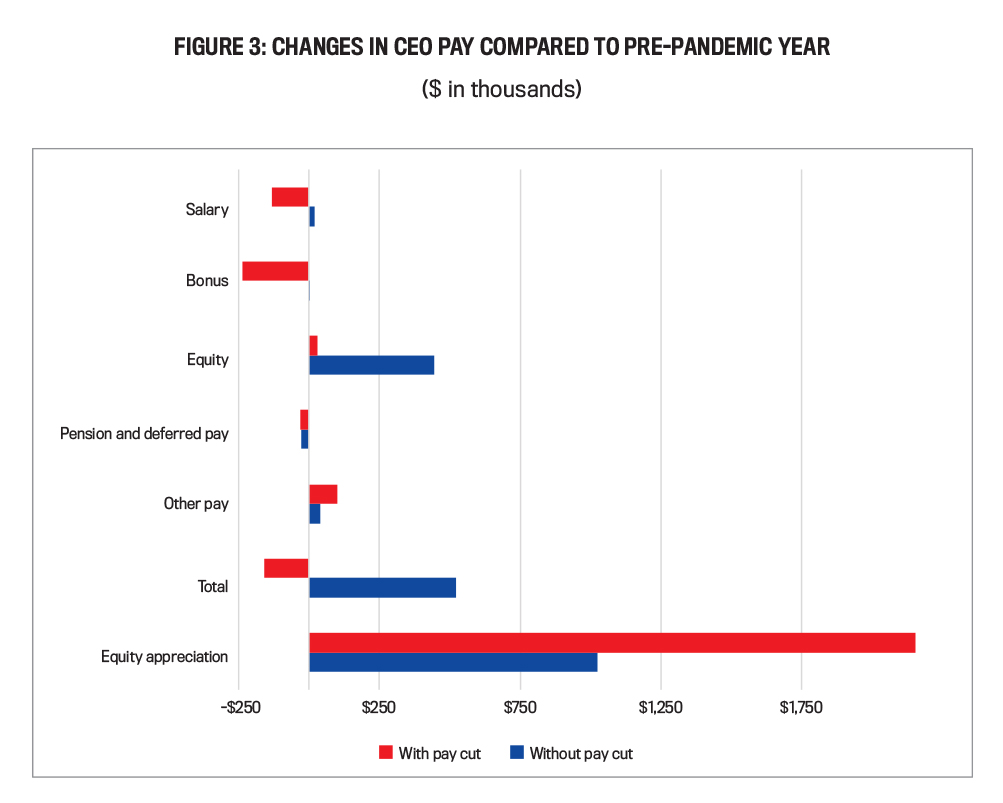

One possible interpretation of our findings is that these pay-cut announcements weren’t motivated solely by the need to protect the economic condition of the company, but rather by the desire to look good in the eyes of various stakeholders. We refer to this motivation in our study as “window dressing.” We found that the stock market responded more positively to the early announcements of CEO pay reductions, suggesting that moves that came later were viewed as weaker attempts at looking responsive. We also found that the market viewed these announcements as favorable in companies where the CEO receives relatively more compensation (as captured by pay ratios) and that have better corporate governance (those with a greater number of independent directors). Presumably, reducing CEO pay in a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic is more likely to have a positive impact on worker morale when average workers are experiencing furloughs, layoffs, or pay cuts and thus is more welcomed by shareholders. All of this suggests that the cuts were economically meaningful and not merely window dressing. In our last set of tests, we examined the magnitude of pay cuts. In the year before the pandemic, companies cutting CEO pay had higher CEO salaries, but not higher total compensation, than those that didn’t cut CEO pay. We analyzed changes in the level of compensation in the pandemic year of 2020 relative to 2019 (see Figure 3). Not surprisingly, companies announcing pay cuts reduced CEO salaries by an average of $129,000 relative to organizations not cutting pay, which in fact had small increases in salaries. Looking at other forms of compensation, companies cutting CEO pay also reduced bonuses and equity grants, culminating in total compensation that was, on average, 3% lower than the prior year, compared to an approximately 6% increase for CEOs among companies that didn’t make cuts.

What’s interesting is that, despite being of lower value at the grant date, the equity grants to CEOs in pay-cutting companies appreciated, on average, $1.13 million more than equity grants to CEOs of companies that didn’t cut CEO salary. Our evidence suggests that salary cuts were accompanied by equity grants when stock prices were low and, ultimately, provided greater value to CEOs who successfully navigated the pandemic waters.

LESSONS FOR FUTURE CHALLENGES

As you can see, many CEOs who took a pay cut didn’t exactly lose out. Replacing salary with equity grants allowed their companies to both conserve cash and maintain incentives for the CEOs to steer their companies through the economic upheaval. Those who did so skillfully were rewarded. But our study of how companies responded to the pandemic also sheds light on how CEO pay can be set in times when there isn’t a pandemic. In annual proxy statements, companies frequently disclose that they benchmark pay levels to those of specified peer companies (that is, their compensation peer group). Nevertheless, the extent to which the observed correlation in annual compensation represents a causal relationship, or a selection of certain peers to ratchet up compensation, can’t be determined without observing the timing of compensation decisions. Because we observed the sequential announcements of pay cuts among peer companies—with some companies being leaders and others followers—we were able to document how the compensation choices of peer companies impact the focal company. We learned that the proportion of peer companies that cut CEO pay has a significant influence on a focal company’s decision to follow suit, and that organizations are more likely to cut pay if the first company in their peer group does so. Our findings suggest that companies benefit when their leadership takes a proactive approach in the face of difficult circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Granted, a global event like this will present corporate executives and boards of directors with any number of very difficult circumstances to deal with. But, unfortunately, everyone from the CEO and CFO to middle managers to the rank and file will more than likely be faced with similar challenges in the future. Learning what we have from this crisis—from the results of our study and anecdotal evidence the world over—has the potential to make all of us, and the companies we support, better prepared for whatever comes next.

May 2022