The award is named in memory of Curtis C. Verschoor, a longtime member of the IMA Committee on Ethics, editor of the Strategic Finance Ethics column for 20 years, and a significant contributor to the development and revisions of the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice. Curt was a passionate, renowned thought leader on ethics in accounting, having earned a Lifetime Achievement Award from Trust Across America–Trust Around the World for his leadership in, and advocacy for, trustworthy business practices.

The Curt Verschoor Ethics Feature of the Year highlights an article that focuses on the importance of ethics in business as a whole and the finance function and accounting in particular issues that Curt deeply cared about.

Over the last decade-plus, corruption has become one of the top risks for global companies due to both the introduction of new laws and stringent enforcements. What can global companies do to mitigate the risks of anticorruption regulation breaches by their employees, agents, or suppliers, which could lead to uncomfortable investigations by law enforcement or regulators? Do self-disclosure, immediate disciplinary actions, and cooperation with government investigators, prosecutors, or regulators mitigate the negative impact of such violations?

A comprehensive, effective compliance program grounded in ethics is the best defense against corruption and legal or regulatory mishaps, but it isn’t always clear what constitutes adequate compliance procedures or how to move beyond baseline policies and procedures to be able to boast of a compliance program that’s legitimately robust.

Corruption has devastating social impacts that are typically worse in poorer countries, many of which are toward the bottom of Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. But unfortunately, bribery is often shrugged off as “just the way you have to do business in some countries” and persists because it often pays off. According to The Economist, every dollar of bribery translates into returns of $6 to $9 if the perpetrators aren’t caught. The development, passage, and harsh enforcement of national regulations such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA) in the United States and international anticorruption laws changed the global business environment significantly and increased the chance that bad actors guilty of committing a violation will pay the full price for their misconduct. Steep fines and other penalties aside, the reputational risk to organizations is grave.

No industry is immune to bribery or corruption anymore. While they used to be significant risks primarily for international oil and gas, mining, arms, and aerospace and defense industries, recent corruption cases are putting verticals such as financial services, pharmaceuticals, automotive, technology, and even international sport in the global spotlight these days.

There have been a significant number of antibribery and anticorruption enforcement actions of late, with the Siemens AG case in 2008 setting a record with more than $1.6 billion paid in penalties and Airbus recently forced to pay €3.6 billion (approximately $4 billion) in fines to the French, British, and U.S. authorities (see “Enforcement Actions” at the end of article). With the extraterritorial reach of national anticorruption laws and coordinated global enforcements, foreign corruption has quickly become one of the top risks of doing business for global companies.

INTERNATIONAL AND EXTRATERRITORIAL NATIONAL LAWS

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (OECD Anti-Bribery Convention), ratified in 1997, was the first anticorruption convention, in which signing countries were required to put in place laws criminalizing bribery of foreign officials. The OECD has no authority to enforce the convention but does monitor compliance and efficiency through its working group. As of today, 44 countries have ratified the convention.

The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), ratified in 2003, is the only legally binding international anticorruption treaty. Overall, 140 countries have signed the convention, in which governments and companies around the world committed to combat bribery and corruption, and the U.N. passed resolutions appealing to member states to do more to fight corruption and bribery. The practical effects of the UNCAC and its resolutions have remained minor, however, as its enactment wasn’t followed by systematic monitoring and enforcement.

Many countries reverted to national laws with extraterritorial reach. The U.S. FCPA was the first national law that prohibits its citizens and corporate entities from bribing foreign government officials and paying politically exposed persons. Starting in 2008, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) increased enforcement of the FCPA. Siemens wasn’t the first international company headquartered outside of the U.S. that was charged with foreign corruption, but it became a significant case in terms of the amount of the fine it was forced to pay and further consequences. It’s notable that, since the Siemens case, the DOJ expanded its extraterritorial reach and began charging companies with limited or no business operations in the U.S. with significant fines.

The United Kingdom followed with the U.K. Bribery Act (UKBA) in 2010, which is similar to the FCPA in that it prohibits both commercial and public foreign corruption but excludes a requirement to acknowledge that the public official acted improperly as a result of the bribe. Additionally, Section 7 of the UKBA notes the “broad and innovatory offence” of the failure of commercial organizations to prevent bribery on their behalf. The UKBA was applied in court for the first time in 2016 with the prosecution of Sweett Group PLC and, later, with a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) with Rolls-Royce PLC.

Germany ratified the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in 1998 and implemented national legislation, the Act on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, which went into effect in 1999. The German legislation prohibited bribery payments and declared them nondeductible for tax purposes, which was permitted previously.

France joined the club with its new law on transparency, the fight against corruption, and modernization of economic life (known as Sapin II) in 2016, which required the creation of a new anticorruption agency, protection of whistleblowers, and the obligation for companies to prevent corruption. It also introduced extraterritorial jurisdictions for offenses committed outside of the country, similar to the U.S. and U.K. laws. The law was tested on the Airbus settlement reached in January 2020 together with U.S. and U.K. authorities.

Over the last few years, more countries brought enforcement actions against companies for foreign bribery and corruption. The list includes Australia, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, and Poland. In Brazil, investigators assisted U.S. authorities to bring Petrobras (Petróleo Brasileiro S.A., a Brazilian state-owned multinational corporation in the petroleum industry) to justice in 2018.

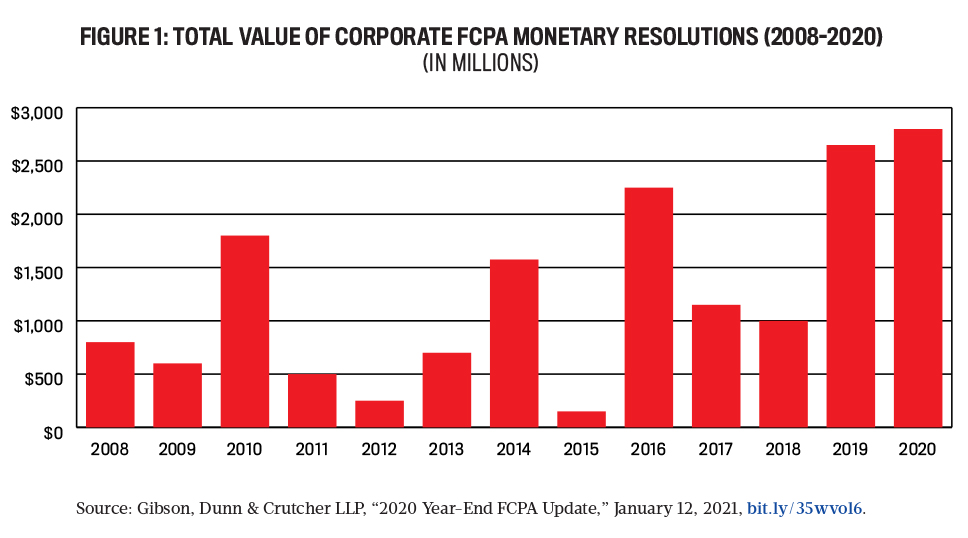

Even though other countries are catching up, the U.S. remains the largest enforcer of anticorruption laws. The number of cases and the aggregate amount of settlements have risen in the last decade, and corporate fines reached a record $2.8 billion in 2020. As of today, there have been 223 completed FCPA cases and five cases under UKBA (see Figure 1).

Companies with operations in high-risk markets find themselves in a different risk and difficult compliance environment. The extraterritorial reach of regulators and better cooperation between authorities mean that multinational corporations must deal with multiple laws and regulations around the world. In addition, there are some risk factors or transactions that could be outside the company officers’ controls and visibility, such as offenses committed by “representatives” (FCPA) or an “associated person” (UKBA), which include not just employees, but also subsidiaries, joint ventures, agents, consultants, and service providers.

The U.S. Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 also introduced whistleblower protection against retaliation and rewards provisions; the latter may entitle the whistleblower to anywhere from 10% to 30% of the settlement amount. Further, governments aren’t always clear about what comprises adequate controls and compliance procedures and what companies must do to prevent every single occurrence of bribery payments by their employees, agents, and suppliers.

EFFECTIVE MITIGATING STRATEGIES AND DEFENSES

Although prevention is the best approach to address foreign bribery risks, sometimes violations happen in spite of headquarters’ best efforts to prevent unethical conduct. In such situations, the company’s management may start planning mitigating and defending strategies and tactics in advance.

“We’ve always done it this way” turns out to be the worst statement for companies attempting to justify a policy or procedure. Referral to established procedures is in fact admittance of one’s negligence, and having negligent management doesn’t help a company trying to defend itself against allegations of corruption or unethical practice while being investigated by the authorities.

Willful blindness, which is a variation of negligence, occurs when a company’s executives suspect a corrupt or unethical practice but carefully and intentionally avoid assessing its legality or investigating it. Refusing to obtain and evaluate information related to malpractice doesn’t establish plausible deniability and won’t insulate individuals or the company from liability. In other words, willful blindness is equivalent to knowledge of corrupt practices for FCPA purposes—purported ignorance of the law isn’t a valid excuse.

Some business leaders may complain that the local business environment is different in other countries, that there are some local protocols where bribery is a common cost of doing business, or even that they’re at a disadvantage to other companies that aren’t bound by antibribery laws or regulations. This argument was effectively addressed in the United States v. Kay (2008) corruption case, where a key excerpt of the judgment reads: “The fact that other companies were guilty of similar bribery...does not excuse [American Rice, Inc.’s] actions; multiple violations of a law do not make those violations legal or create vagueness in the law.”

The “written laws defense” is a further development of the “local protocol” argument, but it has a few nuances. The FCPA principally allows payments permitted by written laws and regulations. But if a foreign government “knew of” or “approved” the scheme, then it’s a loose corollary to conduct permissible by the law. Hence, this “written laws defense” has almost no practical value because no country with written laws explicitly permits bribery.

Further, extortion is a possible defense when public-sector officers demand a bribe while issuing a threat, effectively making the company a victim of a foreign official’s criminal conduct. To use either extortion or the more general “duress” claim, the business must prove that the threat from the government representative was so significant that the payment amounted to an involuntary act. The duress claim relies on proving that the physical threat was serious enough to potentially cause death, that is, it posed a life-threatening risk. When a public-sector official threatens the company’s executive with negative business consequences, however, the company’s managers can walk away, so claims of duress and extortion will be rejected.

In cases such as Siemens and Petrobras, special consideration may influence DOJ decisions with respect to whether or not to prosecute a company or offer a settlement agreement and the magnitude of penalties. Among these circumstances could be the size of the company, any special relationship that it may have with a government’s authorities, the country of origin, and political factors such as elections or other changes that may affect the prosecutors’ judgments. These circumstances, however, are highly specific, and authorities’ reaction to them are highly unpredictable.

COOPERATION, SELF-DISCLOSURE, AND OTHER FACTORS

In reviewing corruption cases, several mitigating factors appear to favorably impact the fines, penalties, and mandatory remedial actions that judges assigned to perpetrators; instances of a nonprosecution agreement (NPA) instead of a DPA (accused companies prefer NPAs over DPAs); and decisions on the potential appointment of an independent monitor (which companies want to avoid, as it can be expensive).

Full cooperation with authorities is considered to be the main mitigating factor at the time of a DPA settlement. It usually includes the accused entity conducting or assisting in conducting investigations; producing data and documents to be shared with the authorities; collecting, analyzing, organizing, and, if needed, translating evidence and information for the prosecutor and other investigative authorities; making senior employees available for interviews; and proactively disclosing some conduct of which the authorities were previously unaware.

Notably, U.S. DPAs have narrower differences in terms of credit given and discounts granted to companies that fully cooperated (e.g., Siemens, Daimler, VimpelCom, and TeliaSonera) and those that received “partial credit” (e.g., Ericsson). The U.K. settlements are too few in number to draw a trend line, but it seems that the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) may have chosen to take a tougher line on uncooperativeness, as Sweett Group’s DPA demonstrated.

The FCPA case involving VimpelCom is one where additional credit and discount were granted for “proactively disclosing some conduct of which the Fraud Section and the Office were previously unaware.” This could be considered a euphemism for pleading guilty. It’s quite a serious step that could potentially lead to further civil lawsuits, however, and corporate defense would only choose such a route in the case of overwhelming incriminating evidence.

The SFO’s Rolls-Royce case was illustrative of a possible outpacing strategy when a company arranged for an independent consultant to play a monitoring role prior to reaching a settlement with the government. Such a strategy provides the accused company with wider flexibility, as the choice for the compliance consultant need not be verified with the prosecutors or judges, and it demonstrates a spirit of cooperation to start monitorship earlier. Additionally, investigative authorities usually consider such a step as clearly indicating the company’s intent to put its house in order and thus are more likely to give the accused credit for it.

In the 2019 Microsoft corruption case, the company was very cooperative with the investigation from beginning to end, but it employed the strategy of defending its position. It argued that there was only one isolated case of proven bribery and engaged in any possible opportunity to demonstrate its strong compliance framework and robust internal controls. Such a defense strategy was expensive, but it bore fruit with a small fine and nonprosecution settlement.

Further, in the Petrobras case, the defense chose the strategy of playing the victim. It achieved partial success in atypical circumstances, but taking such a tack is risky. It will be interesting to see if such a defense approach will be repeated in future corruption prosecution hearings.

DEFENSE ARGUMENTS

In the cases I reviewed, the DOJ prosecution guidance provides credit for establishing a compliance program that highlights the FCPA’s provisions. In fact, in several FCPA cases, including Microsoft and Morgan Stanley, defendants avoided prosecution because they were in a position to demonstrate and prove that they had developed an effective compliance program and a robust system of internal controls. That said, the explicit compliance defense isn’t yet a part of the U.S. antibribery and anticorruption statute.

This line of defense is even more powerful in U.K. corruption investigations. The UKBA specifically criminalizes the failure of commercial organizations to prevent bribery. Section 7(2), however, provides a defense argument if a commercial organization can prove that it had “adequate procedures” in place designed to prevent a person associated with the company from undertaking illegal and unethical conduct.

If adequate compliance procedures and a robust framework of internal controls are such a powerful defense, then is there clear guidance regarding them? The answer originally was no, but case law is developing in both the U.S. and U.K., and a consensus on this issue among prosecutors and judges is starting to emerge over time.

While the DOJ didn’t clearly define the elements of an effective compliance program previously, many DPAs and some NPAs starting around 2014 contained Attachment C, which provides a description of an effective compliance program. It includes (1) high-level commitment, (2) policies and procedures, (3) periodic risk-based reviews, (4) proper oversight and independence, (5) training and guidance, (6) internal reporting and investigation, (7) enforcement and discipline, (8) third-party relationships, (9) mergers and acquisitions, and (10) monitoring and testing.

In February 2017, the DOJ published the first version of Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs, which was develop by Hui Chen, a former compliance attorney at Microsoft. This document has been regularly updated, and the most recent version was issued in June 2020. The evolution of this guidance clearly demonstrates the DOJ’s priorities and what it pays attention to. For instance, the third-party management section was updated with a new question, “Does the company engage in risk management of third parties throughout the lifespan of the relationship, or primarily during the onboarding process?”

Adequate compliance procedures are also taken into account under the U.S. Sentencing Commission Guidelines Manual 2021, which specifies that “the existence of an effective compliance and ethics program” is one of the two factors that a sentencing court should consider in deciding whether to mitigate a sentence. Review of past FCPA settlements demonstrated this application in practice.

Similarly, the U.K. SFO added a chapter on “Evaluating a Compliance Programme” in its Operational Handbook. The six principles of an adequate program are (1) proportionate procedures, (2) top-level commitment, (3) risk assessment, (4) due diligence, (5) communication, and (6) monitoring and review.

Further, adequate compliance procedures must be effective globally. In an ever-changing and expanding antibribery regulatory and legal environment, global companies’ compliance programs must comply with the antibribery laws and requirements of all jurisdictions where they operate.

ANTICIPATING MORE COMPLEXITIES

A review of bribery and corruption cases and settlements over the last decade reveals that the cases have become even more complex. There are at least three dimensions of increased complexity: representative nexus, jurisdictions of law, and coordinated multicountry investigations and prosecutions.

Due diligence on third-party service providers is an integral part of an antibribery and corruption-prevention compliance program. Both the DOJ and the SFO updated their guidance to increase the focus on the quality of meaningful due diligence. But companies still field a lot of questions about how to balance risk-based due-diligence efforts with quality of outcome. The process risks are becoming overreaching, as company representatives could be not just salespeople or other employees, but also consultants, distributors, vendors, suppliers, and members of clubs and charitable organizations. Companies entering into joint ventures in a foreign market sometimes open themselves up to an entirely new universe of risks.

Since the Siemens case, questions have been raised about the FCPA’s jurisdiction. U.S. authorities are routinely successful at finding a way to apply jurisdiction. The FCPA is applied to cases where jurisdiction may be difficult to prove; the U.S.’s extraterritorial reach to prosecute corruption cases has become common. For example, Airbus is a European company and Petrobras is Brazilian, but U.S. authorities spared no effort to demonstrate that they had proper criminal jurisdiction over the case. Whether it was Petrobras’s shares trading on the New York Stock Exchange in the form of American depository shares, Airbus’s subsidiaries’ venue of incorporation, incriminating emails sent by a company representative to or from a location in the U.S., or corruption conspiracy discussions during a Hawaii vacation, U.S. authorities established their jurisdiction.

The Airbus case also showed an increased pro-extraterritorial stance in the U.K., and it was the first judicial interpretation of the extraterritorial-reach clause of the UKBA’s Section 7. Airbus is registered in the Netherlands, has its operational headquarters in France, and admitted to facts that occurred outside of the U.K.’s border. In fact, a U.K. nexus was mainly generated by Airbus’s decision to agree to U.K. jurisdiction.

Another unexpected element is the growing trend of coordinated anticorruption prosecutions. The Airbus settlement again serves as a recent example. That case was the result of a joint investigation between France’s Parquet National Financier, the SFO, and the DOJ. As a result of U.S. jurisdiction over foreign companies and because the U.S. has the strongest investigative capabilities, authorities in the country or countries in which an offending company’s headquarters is located will gladly join a U.S. investigation to benefit from the final settlement distribution.

The Airbus investigation and other cases clearly demonstrated that cooperation among law-enforcement agencies in different countries is reaching new heights. As cross-border cooperation, information sharing, and joint prosecution become ever-present parts of enforcement actions against corporate crime, companies should be aware of the full scope of their potential jurisdictional liability.

It’s widely felt that most FCPA and UKBA cases are decided in prosecutors’ offices, where accused companies often agree to costly settlements rather than engage in risky legal fights. In fact, corruption settlements have become so prevalent that virtually all bribery investigations have resulted in settlements or guilty pleas.

There are several reasons that settlement is widespread in corporate criminal cases. Defending an allegation of corruption in court is expensive. Corporations prefer not to take FCPA cases to the courts due to uncertainty, the expense of legal fees, and the potential for reputational harm. But because of the very low number of precedents from cases tried under FCPA, there is considerable uncertainty around fighting a corruption allegation in court.

While both the DOJ and the SFO expect organizations to conduct thorough internal investigations and to apply disciplinary measures for infractions, individual executives are rarely prosecuted. DPAs usually don’t include plea bargains, but in many cases, they defer any further prosecution by the government. Both U.S. and U.K. prosecutions reward cooperation that leads to prevalent practice of using DPAs or NPAs. In the U.S., FCPA prosecutions have turned into a cash cow for the DOJ, which may indicate the future for U.K. bribery prosecutions.

Increasing vigor in enforcement combined with ambiguous or unpredictable prosecutorial decisions creates a significant deterrence effect, and detailed guidance from authorities enable companies to fine-tune their code of conduct, ethics or mission statement, and compliance programs. On the other hand, the low number of judicial precedents due to a culture of settlement maintains unnecessary uncertainty—not just in the U.S., but also in countries with relatively new foreign antibribery and corruption legislation.

The deterrence effect and the rapid development of ethics and compliance programs are the main consequences of more stringent application of foreign corruption laws. In fact, some lawyers argue that governmental authorities deliberately maintain ambiguity and manipulate uncertainties in the law to ensure greater deterrence. That said, while inherent prosecutorial discretion remains a variable, companies have a larger number of cases to study, and governments have published more detailed guidelines with articulated consequences. Extrajudicial enforcement provides both a deterrence effect due to harsh sentences and fine-grained guidance concerning effective anticorruption compliance programs, which encourage companies to implement effective measures.

The main defensive strategy that really works is a combination of a strong compliance program, a mature ethical culture, and robust internal controls to deter and uncover isolated incidents of misconduct. Although prosecutors often credited companies for cooperativeness and assistance in an investigation, it didn’t correlate with a significant reduction of fines or a principal difference in other outcomes such as not requiring an expensive monitor appointment.

A robust compliance program has shown to be a major mitigating factor in FCPA cases, and under the UKBA, taking “adequate measures” is an affirmative defense. Since the passage of Sapin II, French enforcement officials have started taking a similar stance to their American and British counterparts. Accordingly, in response to these case studies and national authorities’ guidelines, companies have no real choice but to make an ethical pledge to enforce a stringent anticorruption regime and comprehensive compliance program, in addition to articulating their commitment to ethics with a code of conduct, to minimize their risk of incurring criminal liability for corrupt behaviors such as bribery under the laws of various countries.

Any views or opinions presented in this article are those of the author and not his current or former employer.

Enforcement Actions

2008 - Siemens AG

In 2008, Siemens AG settled an FCPA violation with $450 million in criminal fines to the DOJ and a $350 million payment to the SEC. Along with the payment to the Munich Public Prosecutor’s Office, Siemens paid a combined total of more than $1.6 billion in penalties, fines, and disgorgement of profits.

2010 - Daimler AG

German corporation Daimler AG and its three subsidiaries struck a DPA with the DOJ and the SEC related to an FCPA investigation into the company’s worldwide sales practices on April 1, 2010. Daimler and its subsidiaries paid $185 million in both criminal and civil fines and penalties to U.S. authorities.

2016 - VimpelCom Ltd.

VimpelCom Ltd., a multinational company headquartered in Amsterdam, was one of three international telecom operators accused of paying bribes in Uzbekistan. In February 2016, the DOJ, the SEC, and Dutch regulators announced a global settlement with VimpelCom with a DPA, more than $795 million in fines, and a three-year monitorship program, after which it changed its name to VEON.

2016/2017 - Rolls-Royce PLC

Rolls-Royce PLC, a British engineering company, signed a DPA with the DOJ in December 2016 and the U.K. SFO in January 2017, agreeing to pay a $170 million fine in the U.S. and £497.2 million plus interest in the U.K. In Brazil, Rolls-Royce reached a leniency agreement with Brazil’s Ministério Público Federal with a fine of $25.5 million.

2017 - TeliaSonera

TeliaSonera, a Swedish multinational telecommunications company and mobile network operator, was involved in an Uzbek telecom corruption scandal along with VimpelCom and Mobile Telesystems. In 2017, Telia reached a global settlement with the DOJ, the SEC, and Openbaar Ministerie, the Dutch Public Prosecution Service, after an investigation into its transactions in Uzbekistan. The company agreed to pay nearly $966 million in penalties and fines. In addition, Swedish prosecutors filed charges against three senior executives.

2018 - Petrobras

Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras), a Brazil-based state-owned oil and gas company, settled the U.S. government’s investigation with $853.2 million in penalties in an NPA. It also agreed to pay an additional $933 million in disgorgement and prejudgment interest to resolve the SEC investigation. The total amount of $1.8 billion was the biggest fine in the FCPA’s history, out of which $682.6 million (80% of the criminal penalty) is funding “social and educational programs to promote transparency and compliance in Brazil’s public sector.”

2019 - Microsoft Corporation

Microsoft Corporation ended its seven-year FCPA investigation with a settlement in July 2019. Microsoft paid the DOJ and the SEC $25.3 million to resolve the case, including $13.78 million in fines and prejudgment interest of $2.78 million, in connection with its operations in four different foreign-based subsidiaries in Romania, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and Turkey. In addition, Microsoft Hungary agreed to pay a criminal penalty of $8.7 million.

2019 - Ericsson

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson, a Sweden-based global telecommunication equipment manufacturer, was charged with a large-scale bribery scheme and settled with both the DOJ and SEC by entering a DPA. It agreed to pay more than $1 billion and to appoint an independent compliance monitor. Ericsson Egypt Ltd., a subsidiary, pleaded guilty to criminal charges and conspiracy to violate the antibribery provisions of the law.

2020 - Airbus

2020 started with the record-breaking bribery and corruption settlement in history. Airbus paid €3.6 billion (approximately $4 billion) in total to settle the case, including €3.6 million in France, €991 million in the U.K., and $526 million in the U.S.

March 2022