Like in most areas of life, it’s generally good to have a lot of choices in accounting. Take, for instance, activity-based costing (ABC) and value-stream costing (VSC), which can be viewed as two alternative approaches to obtaining accurate cost information in complex production and sales environments. You would think that companies that adopt VSC aren’t likely to also have ABC systems. But that isn’t necessarily the case: A 2012 survey of 368 facilities employing Lean production found that 62 of them—or roughly one in six—reported a relatively high use of both ABC and VSC. Those same companies also reported the highest level of performance improvement from Lean initiatives. Clearly, these organizations weren’t treating ABC and VSC as alternatives: They were using the systems in tandem.

In an article titled “Lean Accounting and Activity-Based Costing—A Choice or a Blend?” (Cost Management, January/February 2019, pp. 5-15), Gary Cokins proposed that companies could use both Lean accounting (VSC, in this case) and ABC, with each serving a different purpose. He suggested that managers could use Lean accounting to focus on operational improvement, while ABC could be used strategically to better understand the drivers of company profitability. Cokins makes the case for using ABC and Lean accounting together, and he presents a model of how a dual ABC/Lean system could be structured and used.

ABC AND VSC: A DUAL-SYSTEM MODEL

Companies producing and selling a variety of products face the challenge of generating accurate cost information for decision making and control. One way to respond to this complex production and sales environment is to develop an ABC system—a cost accounting system that captures in detail the cause-effect relationships between activities and costs.

The rise of Lean production and Lean management created an additional challenge for generating accurate cost information, but it also gave rise to an alternative solution. To improve flow and reduce waste, Lean production and sales systems reduce batch sizes, which greatly increases the number of transactions (purchases, deliveries, setups, internal transfers, shipments, etc.). Not surprisingly, a greater number of transactions increase the cost of maintaining a complex ABC system. The Lean solution is to organize and report by value stream the set of all activities used to produce and deliver a product or service. Products can be organized into groups that follow approximately the same production flow. Each product group, however, is treated as a separate value stream.

With a value-stream organization, most of the variation in resource usage is between value streams, not within value streams. In addition, the value streams are usually large enough to have dedicated resources, greatly eliminating the need for cost allocations between value streams. In this setting, the added value of an ABC system is greatly reduced. The value stream, rather than the individual products created within it, becomes the focus for cost control and performance improvement. As such, value-stream income statements based on actual costs are easily understood by workers in the value stream.

The dual-system model presented by Cokins envisions an enterprise ABC system, using cost drivers to assign all resources to appropriate cost objects (suppliers, product orders, customers, and sustaining activities, for example). The same system would sum the costs assigned to all the activities in the value stream to generate a horizontal, process view of costs. Cokins depicts departments in his process view. In a company organized by value streams instead of functional departments, production cells would replace departments or the costs would be assigned directly from the work activities to the value streams. Essentially, he proposes a complex ABC system with flexible reporting.

While it certainly would generate easily understandable value-stream income statements, the ABC system could be expensive to maintain, particularly in a Lean environment, and it wouldn’t offer the simplification and savings available from VSC systems. With this in mind, we wanted to find a company actually using VSC and ABC in tandem that would share its experiences related to the design and use of these two approaches.

HOW ONE COMPANY MAKES IT WORK

LINAK, a family-owned company with headquarters in Denmark, agreed to share its experiences with us. The company name is a contraction of the Danish words for linear actuators, the company’s main product focus. Linear actuators electronically change the level or position of, among other things, tables, chairs, workstations, beds, solar panels, and industrial and agricultural equipment.

Currently, LINAK has production facilities in Denmark, Slovakia, the United States, China, and Thailand, and sales and marketing subsidiaries in 31 countries. It has more than 2,400 employees and annual sales of approximately $645 million. The company has roughly 250 products spread over seven value streams, which it refers to as segments. The segments are further broken down into production cells and about 20 departments (collections of production cells). Most of LINAK’s departments are dedicated to a single segment, but a few are shared by more than one segment.

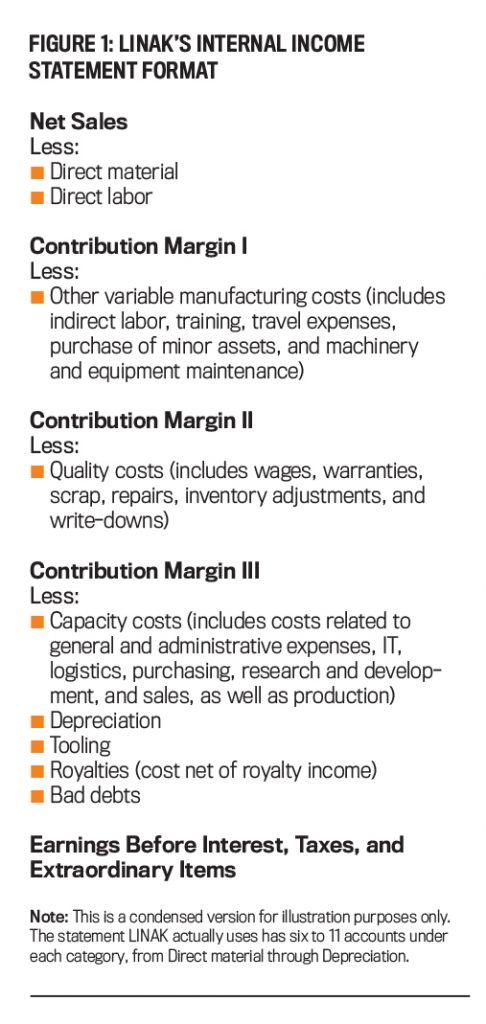

LINAK’S REPORTING BY VALUE STREAM

A condensed version of LINAK’s internal income statement reporting format is shown in Figure 1. Direct material and direct labor costs are initially recorded at standard in the company records, but they’re adjusted to actual period costs in the company’s internal monthly income statements. Standard direct material costs are developed using the bills of materials for each product. LINAK defines direct labor very broadly. Essentially all the time a worker spends in a production cell is considered direct labor. LINAK’s approach simplifies the accounting system, eliminating the need to track labor with multiple job or activity codes. Direct labor costs are recorded in the primary production cell to which each worker is assigned. LINAK only needs to record additional labor transactions if the worker leaves that primary cell to provide assistance elsewhere. Products created in each segment follow roughly the same production processes, but they vary significantly in time consumed within each process. LINAK computes a standard number of labor hours required for each product it makes.

LINAK’s accounting system traces variable manufacturing costs and quality costs to product type, which allows for more detailed tracking than the segment but a higher level of aggregation than an individual product ID. Most production equipment is dedicated to product segments, so most equipment depreciation is a direct cost for the segments. Capacity costs and depreciation are also traced to product type.

COST CONTROL MEASURES

LINAK’s management uses a combination of nonfinancial and financial measures for cost control. A key nonfinancial measure is day-by-the-hour production. Display boards post the planned and actual units produced each hour. These boards quickly reveal production problems, including overproduction, so that causes of the problems can be discovered in real time and countermeasures can be quickly developed and deployed. Segment, department, and production cell leaders also focus on measures of efficiency, quality (parts per million failures), and lead time. Efficiency is measured by comparing standard direct labor hours for actual production to actual direct labor hours. Standard direct labor hours provide an equivalent unit of production (and sales) for all of the products created in a segment, so the measure won’t be distorted by changes in production and sales mixes.

The most important financial measures for LINAK’s segment and department managers are the three contribution margins reported on the internal income statements. The margins show the segment’s contribution to covering other costs and adding to profit after deducting categories of variable manufacturing costs from revenue: first direct material and direct labor, then indirect variable production costs, and, finally, the costs associated with defects and nonconformance.

The managers especially focus on Contribution Margin I (revenue less direct materials plus direct labor). Their direct material costs have shown the most variability, but the managers also focus on direct labor. In addition, they examine the trend of the ratio of direct labor costs to revenue (Contribution Margin II) and compare this ratio to a target level. They also examine the difference between margins II and III, which really draws attention to the cost of defects and nonconformance.

LINAK’s chief operating officer and the segment, department, and production cell leaders meet weekly to review the nonfinancial key performance indicators and the financial results, with a particular focus on the 12-month trends. The financial results are also compared to the annual static budget, but this comparison is less important and more for financial planning than for cost control. Although the production employees focus more on the nonfinancial metrics, the financial results are shared with the workers, who maintain a high level of awareness of the financial performance within their segments and departments.

THE ABC SYSTEM AT LINAK

Although LINAK has organized into segments that contain products with a similar production flow, many of its customers buy products from multiple segments. Sales, distribution, and marketing costs are therefore shared costs for the segments.

In 2006, LINAK hired a consultant to help develop an ABC system to see how marketing and distribution costs varied across the customer base. The consultant stressed that this wasn’t just an accounting department project—it required the engagement and support of the entire top management team. Together, they identified between 80 and 100 cost drivers, mostly transactional (number of orders, shipments, etc.) that were primary drivers of the company’s marketing and distribution costs.

LINAK headquarters in Nordborg, Denmark. Photo courtesy of LINAK.

Each year, middle managers conduct a study to update the model. Cost driver rates are determined using current costs and the full capacity for each cost driver, available with the resources in place. This annual study takes no more than one day. Model rates are then used throughout the year to apply costs to cost objects based on the actual use of the cost drivers. LINAK’s managers recognize that relying on an annual update based on a one-day study comes at the cost of some accuracy. Nevertheless, they feel they’ve attained a reasonable and sufficient level of accuracy for a minimal cost. (Recognizing that its ABC model is based on full capacity, LINAK suspended its use during the severe recession of 2008-2009.)

LINAK’s ABC system was also extended to create a total cost of ownership (TCO) model, with suppliers and parts as the cost objects. The TCO model, implemented 10 years ago, is used to compare remote suppliers from foreign countries with local suppliers. The model hasn’t been changed, but the rates used for comparison are updated regularly. Using simpler allocations for indirect costs not included in the ABC model (such as traditional volume-based drivers, where appropriate), LINAK’s system can instantly provide allocations of all relevant costs by customer, customer group, supplier, segment, product, and product family.

A STRATEGIC APPROACH

Using the ABC information, LINAK found that its marketing and distribution costs differed across five categories of customers: global customers; very large single-nation customers; and large, medium, and small “other” customers. Recognizing these differences has helped LINAK refine its strategies and approaches for interacting with these various categories of customers.

LINAK’s product pricing is primarily based on market conditions and negotiations with customers. The company computes a variable product cost per unit, which is used as a floor price in negotiations, in addition to the ABC information on marketing and distribution costs. The accounting department prepares a short PowerPoint presentation on these costs for each customer meeting, which the sales managers use to negotiate changes in prices, products, and delivery terms or methods.

LINAK’s managers have found that customers, especially those based in the U.S., appreciate the ABC information, feeling that it adds transparency regarding overall costs and enables better-informed purchasing and delivery decisions. In a similar way, LINAK uses the TCO information to negotiate with its suppliers of materials, parts, and components.

ASSESSING LINAK’S SYSTEM

LINAK’s accounting system has many characteristics of Lean accounting and VSC. The company relies primarily on nonfinancial measures to control the activities that are driving production costs. It treats all production work in the value stream as a single direct labor category, greatly simplifying labor tracking and eliminating the entries by job or process code that typify traditional standard cost systems.

Despite all this, LINAK doesn’t have a “pure” VSC system, preferring to use standard direct labor costs in inventory valuation. It could entirely drop the use of standard labor costing and adopt a simplified system of inventory valuation to satisfy external reporting requirements. (Before it could adopt a simplified method of inventory valuation, the company would very likely have to reduce its overall inventory levels, which are currently fairly high. Most companies that drop standard costing and adopt simplified inventory valuation methods make the change after increasing their inventory turnover rate to 10 or 12.)

LINAK computes overhead variances for direct labor but relies on the trends in nonfinancial measures of efficiency, quality, and lead time, and its three contribution margins for cost control. It doesn’t compute or report on indirect manufacturing overhead variances or overhead absorption variances for fixed manufacturing costs.

LINAK doesn’t report segment margins on the internal income statements, though its system could easily do so. Instead, the company’s cost control focus is on variable production costs at the segment level rather than on overall segment costs and segment contribution margin; fixed costs are controlled at the facility level rather than at the segment level. LINAK also allocates costs to product types within the segments. Overall, the company appears to do more analysis of cost by product and product type than advocates of VSC would suggest.

By creating an ABC model for customer-related costs, LINAK solved an information problem that may be common to many manufacturing companies. Marketing and distribution costs are shared costs for LINAK’s production value streams, and its customers use those resources with varying levels of intensity. VSC, however, is unable to reduce the heterogeneity of customer-related costs under these circumstances. Yet by using ABC in tandem with VSC, LINAK’s system is able to efficiently provide reasonably accurate product and customer-related cost information. Lean manufacturers facing similar conditions may have found the same solution, which may explain why some companies report using both VSC and ABC.

DON’T BE AFRAID

Lean consultants are typically wary of using ABC information because they’re afraid managers will attempt to reduce transaction-related costs by lowering the number of transactions (the number of shipments, for example). From a Lean perspective, larger, less frequent orders and shipments produce unevenness and impede flow. These effects will be reflected in measures of lead time and perhaps quality, and the waste will be reflected in the cost data. But there may be a lag between the decision to reduce orders and shipments and the effects on lead time and costs.

Examples of LINAK products: linear actuator LA36 (left), lifting column LC3 (right). Photos courtesy of LINAK.

This isn’t a flaw in the ABC information. Rather, it’s a problem of managers viewing the transaction cost information with a conventional, rather than a Lean, mindset. In negotiations with customers, LINAK’s managers should therefore focus primarily on reducing the cost of performing transactions and on modifying the customer orders and shipping in ways that reduce unevenness and improve flow.

LINAK’s accounting and reporting system isn’t an example of an ideal VSC system, nor is it an example of an ideal ABC system. That said, LINAK’s management isn’t in the business of creating a model accounting and reporting system. It simply wants a system that provides the information managers and employees need to control costs, make strategic business decisions, and satisfy external reporting requirements. The company’s accounting and reporting system is tailored to its needs, and it will evolve as its business evolves. And, like all processes, the system is subject to continuous improvement to eliminate waste while maintaining or increasing the value provided.

HOW DOES YOUR SYSTEM COMPARE?

We believe that, in its current state, LINAK’s accounting and reporting system represents an excellent example of a company using Lean accounting and VSC principles in tandem with ABC to provide more relevant and more understandable information while reducing the overall cost of its system.

Of course, LINAK is just one example of a company making extensive use of VSC and ABC to improve the overall capabilities of its system. We have no idea whether or not its approach is typical of companies that employ both VSC and ABC. If your company uses VSC and ABC in tandem, we would love to hear how your approach is similar to or different from LINAK’s system. Our contact information appears at the end of this article, so please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

Whether or not your organization uses ABC and VSC in tandem, we hope that our description of LINAK’s accounting and reporting system gives you ideas for improving accounting and reporting at your company. In a hypercompetitive global environment, a well-considered, timely adjustment here or there may make all the difference.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank Carsten Borchert, LINAK’s CFO, for his willingness to share information about LINAK’s accounting and reporting system and for the time he devoted to explaining its details and answering our questions.

The Marriage of VSC and ABC: How You Can Benefit

Very few companies tie together VSC and ABC. But those that do—including LINAK—report success with this hybrid approach. Here are some of the advantages:

- VSC cost statements are easily understood by production workers in the value stream. They report actual costs of the value stream each period. Most, if not all, of these costs are direct costs of the value stream.

- VSC allows the accounting system to be simplified. The need for cost allocation is reduced because more resources are dedicated to individual value streams, and there’s low variability in resource use by products within each value stream.

- VSC supports and motivates continuous improvement in operations by clearly showing the financial impact of improved operations within the value stream.

- ABC can provide customer costs for shared marketing, sales, delivery, and support resources where customers are served by multiple production (order through delivery) value streams. These costs can be used in customer negotiations to change terms and/or prices, creating win-win solutions.

- ABC can provide total cost of ownership information on suppliers. This information can be used to select suppliers and in negotiations to change terms and/or prices—once again, creating win-win solutions.

- ABC can be extended to provide individual product costs where there’s still significant variability in resource use by products within the value stream. The ABC product cost information can be used strategically to identify high-market-value, low-cost products and strong potential targets for kaizen (continuous improvement) events.

Tips for Using VSC and ABC in Tandem

From our experience, it’s one thing for an organization to commit to a VSC/ABC hybrid approach and quite another to pull it off successfully. Here are a few things your management team should keep in mind before going all in:

- Organizing by value stream rather than by functional department is essential for VSC.

- Dedicate as many resources as possible to individual value streams. Direct costs at the value-stream level eliminate the need for cost allocations.

- Rely primarily on nonfinancial measures to control operations; this can improve production flow, quality, and delivery, and eliminate waste and unevenness.

- Use financial measures of value-stream performance to ensure that operational improvements are yielding improved financial performance.

- If an ABC system isn’t already in place, develop one for resources shared by the value streams, especially customer-related activity costs.

- If a comprehensive ABC system is in place but VSC isn’t, use each value stream as a cost object to create value-stream income statements.

- Use ABC cost information on customers and suppliers for strategic planning, identifying strong potential customers and suppliers.

- Use ABC for product cost information if desired and if there’s significant variation in activity use by products within value streams. ABC product costs should be used strategically, recognizing they include shared value-stream costs.

- Use value-based pricing, rather than cost-based pricing, whenever possible.

March 2022