This article is based on research funded by a grant from the IMA® Research Foundation.

Though the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 made remote work the norm for many, it had already become more common. A 2015 Gallup poll found that 37% of U.S. workers had telecommuted, while a 2019 Global Workplace Analytics survey found that 40% of surveyed companies offered flexible workplace options. Of course, those numbers jumped significantly in 2020. A global survey by Gartner found that 88% of business organizations mandated or encouraged employees to work from home as COVID-19 spread. It’s unclear how many employees will continue to work remotely as the world adjusts to the new normal, but in general, remote work is a global workplace trend that appears to be here to stay.

Questions still revolve around the impact this will have—on individual employees, company operations, performance, and so forth. As a manager, you may have found yourself asking questions such as “How will remote work affect my employees’ behavior?” “Will my management teams continue to review and push back on subpar work while being remote?” “How will employees respond to being physically distant from their managers?” We conducted a research study to look at these issues, and the results provide some interesting insights.

We designed a reporting task where employees request budgetary funds, and we examined the impact that the remote working environment and managerial review have on the employees’ honesty regarding their budgetary needs. The results indicate that managers’ approval authority significantly increases employees’ reporting honesty in the remote reporting environment but not in a nonremote reporting environment. Remote employee-participants were more cognizant that building slack into their budget hurts the owner and, thus, had more concerns with being honest in their reporting. Interestingly, employees’ perceptions that the manager would be more or less likely to reject budget requests were the same whether or not budgetary requests are remote. Rather, working remotely appears to heighten employees’ empathy for those individuals affected by their reporting decisions.

WORKPLACE EMPATHY

Empathy is an “other-focused” emotional response that allows an individual to connect with and feel concern for another individual. Empathy is a function of both an individual’s natural disposition to feel empathy (trait empathy) and the environment the individual is currently in (state empathy). For an employee, that would be the workplace.

Workplace empathy is determined by the collective capacity of employee empathy within an organization, but managers can make several decisions within an organization to influence workplace empathy. As shown in Figure 1, the first input into workplace empathy is employees’ dispositions toward empathy. Positive reinforcement of specific behaviors can increase an individual’s propensity toward that behavior. For example, if you, as a manager, see an employee offer to cover the shift of a sick coworker, that individual is more likely to become predisposed to engage in that type of behavior again if you positively reinforce the behavior—even through something as simple as a “pat on the back” or a thank-you card.

Another factor that can influence employees’ dispositions toward empathy is whether the work environment is conducive to empathetic decision making. A number of psychology studies suggest that remote work can lead individuals to contemplate their job in an “abstract” mindset, which leads them to consider higher-level behavioral norms and principles. That is, not going to a physical office and not seeing coworkers on a daily basis can cause individuals to think about their work more abstractly. As individuals think about concepts more abstractly, it tends to broaden their thinking and decision making, increasing empathy. This is often why a common piece of advice, when one is faced with a tough decision, is to think what you would say to a friend in the same situation. It causes the decision to become more abstract (by removing yourself from the decision), which can help with sound decision making. Thus, employees who work remotely are likely to be in a work environment that’s conducive to empathy.

Another way that remote work can create an environment conducive to empathy is through extra time. Remote work reduces commute time, requires fewer unnecessary meetings, and reduces distractions that can occur while in the office. This can leave more time for thoughtful consideration when making decisions. In some circumstances, quick, rushed decisions can result in more egocentric outcomes, while more deliberative decisions can result in more empathetic outcomes. This suggests that sometimes companies implementing controls that directly or indirectly cause employees to slow down and make more deliberate decisions will likely see greater workplace empathy than those companies without such controls.

The next factor that can influence workforce empathy is leadership. The adage “practice what you preach” comes into play here. If employees don’t see the leadership team showing empathy, it’s unlikely that they will show it themselves. So how can a leader show empathy? There are a number of options, ranging from small, individual actions to large-scale organizational efforts. For instance, leaders can implement organizational initiatives to show that empathy in the workplace matters, such as charitable contribution matches or having the company engage in pro-social activities.

It also doesn’t need to be complicated. We’ve mentioned the value of a small gesture like a pat on the back to show appreciation to employees who show empathy. In addition, the simple act of “checking in” on employees can create an opportunity for candid discussions and connections. For example, supervisors can reinforce empathy simply by stopping by their employees’ desks (or scheduling occasional catch-up calls for remote workers) and asking how things are going. It’s important that these check-ins be genuine, not a forced precursor to a work assignment.

One critical element of empathy is showing consideration for another person by being friendly, supportive, and concerned. While this might feel like another item on the never-ending checklist of things to do, consider the benefit: Research suggests a negative correlation between leadership empathy and employee-turnover intentions. Consider the impact that the pandemic has had on employees. For example, have you had a virtual meeting with colleagues interrupted by a child who couldn’t attend school because of a COVID-19 outbreak? How did you react? Most of us understand how the pandemic turned life upside down, so we respond with patience and understanding because we feel empathy for our colleagues.

The external environment also can influence workplace empathy. While managers can’t always control the external environment, the actions they take when they see workforce empathy can reinforce that type of behavior. Following the 2010 Haiti earthquake, UPS set up a blog that allowed employees to comment and communicate about the disaster, allowing them to share their feelings about it. This provided employees with a clear signal that UPS valued employee empathy with what was going on in the external environment. These types of decisions can have a profound influence on workplace empathy.

It’s against this backdrop that we set out to examine whether empathy influences employee budgetary reporting behavior. We contend that greater empathy will lead to higher levels of honesty in budgetary reporting and that a managerial review of budget reports will have an “extra” empathy benefit when implemented in a remote work environment. In particular, a middle manager’s ability to approve or reject a budget will cause employees to deliberate more thoughtfully on their budget report, causing them to think about how their reporting decision affects others, which will further boost the heightened levels of empathy associated with remote work. Ultimately, we predict that the positive effect of managerial approval authority on honest reporting is stronger in a remote work environment vs. an in-person environment.

OUR EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

Our research involved 282 business students from a public university. We used undergraduate students as participants for three reasons. First, the psychological theory about the effect of abstractness on empathy and honesty isn’t specific only to individuals in a workplace setting. As such, we believe our results using undergraduate students to test this theory would generalize to individuals in the work setting. Second, it would be quite costly to run a study with meaningful financial incentives for people working a full-time job. To the extent that we wanted our participants to consider the financial ramifications of their choices, it would be cost-prohibitive to use actual owners, managers, and employees in a company. Finally, graduating college students will be entering the workforce, and, independent of our first two reasons, there’s value in understanding how college students respond to remote environments and controls.

We randomly assigned participants to the role of an owner, middle manager, or employee, and provided them with detailed instructions on their role, the task, and their compensation. For about half the participants, the reporting decision and the rejection decision took place on campus in a computer laboratory. For the other half, participants logged into a Webex meeting room to perform the task on their home computer. Similarly, for about half the participants, managers could reject employees’ budget reports. For the other half, managers couldn’t reject the employees’ budget reports. To help ensure that the results were being driven by these differences, we kept all other variables constant across conditions as much as possible.

For the reporting task, the employee submits a budget request to the manager for funding of a project. This project generates revenue of $4,000 through the sale of a product. The production cost of the employee’s project ranges between $2,000 and $4,000, in $50 increments, and is randomly determined each round. The employee knows the actual cost, the manager knows whether the employee’s actual cost ranges between $2,000 and $2,950 or between $3,000 and $4,000, and the owner only knows that the employee’s actual cost ranges between $2,000 and $4,000. We allow the manager to have a signal of the employee’s actual cost (either in the upper or lower half of the cost range) to ensure that the manager has an informational advantage over the owner, which provides a basis for delegating budget approval authority to the manager.

After completing the reporting task for 10 rounds, participants answered questions about their experience, including how their reporting decisions influenced their owners and how important they thought it was to report honestly.

REMOTE REPORTING EVOKES GREATER EMPATHY

To assess empathy, we asked three questions to gauge the extent to which employee-participants took the perspective of owner-participants. In particular, employee-participants allocated 100 points over the factors that they believed influenced their budget reporting decisions, with more points indicating greater influences. These factors included:

- F1—report a budget that’s equal or close to my actual cost,

- F2—the owner receives a fair payoff, and

- F3—maximize my own earnings.

We created a measure of empathy using the weights assigned to these factors (F1 + F2 – F3). We found that the highest level of empathy occurs in a remote reporting environment when middle managers have approval authority.

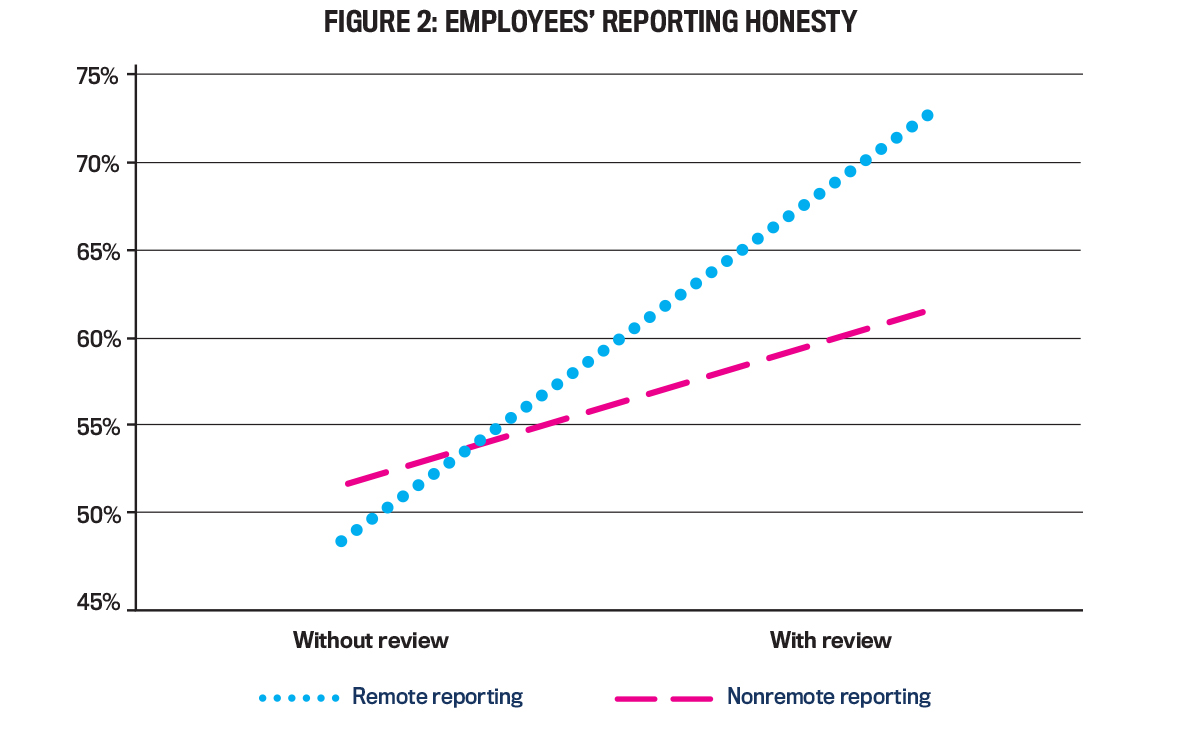

Next, we looked at the actual reporting decisions made by employee-participants. We found that the highest level of honest reporting occurs in a remote reporting environment when middle managers have approval authority (see Figure 2). The average honesty of employees in that scenario was 72.2% [measured as 1 – (budget – actual cost) /(maximum cost – actual cost), where 0% is fully dishonest and 100% is fully honest]. When managers didn’t have approval authority, remote workers’ honesty was 48.9%. This reaffirms the importance of a formal control designed to approve or reject employees’ budget reports when they’re reporting remotely.

We also found that this control has a stronger effect on employee honesty when employees are reporting remotely compared to when they aren’t remote. Employees in the nonremote reporting environment were 61.2% honest when managers had approval authority and 52.2% honest without managerial review.

It’s important to note that these findings do occur in a stylized experiment we designed to test our theory cleanly. Thus, we excluded certain external factors. For example, employees in an actual company could be more sensitive to the possibility of job loss when working remotely during the pandemic, and thus they’d report more honestly. Because the student-participants couldn’t be “laid off” from the experiment, this factor is unlikely to drive our results. This highlights the need for additional research examining reporting decisions in remote vs. in-person environments.

To say the COVID-19 pandemic has altered the work environment is an understatement. A large number of employees are working remotely, and one possible concern is how remote work is altering situations where employees must self-report information, such as budgetary costs. The results of our research suggest that remote reporting can lead to employees having greater empathy for owners, which leads to higher levels of honesty. We provide evidence that a heightened sense of empathy from remote reporting could offset some worries about the quality of reporting while workers are remote.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support received from the IMA Research Foundation and the University of Kansas.

Increasing Workplace Empathy

- Reinforce moments where employees show empathy in the workplace. For example, if you see an employee going out of their way to help another coworker, let that person know that you appreciate the effort.

- Model empathy by stopping by your employees’ workstation to ask how things are going. If possible, don’t assign additional work or things of that nature during this conversation.

- Provide an outlet for employees to discuss how the pandemic or other issues have affected them personally and professionally.

- Highlight pro-social activities in which your organization engages. This reinforces to employees that empathy is important in the organization.

- Practice perspective taking in which you actively take time to put yourself in the position of your employees and think through what they’re experiencing.

- Create shared experiences with your employees. For example, if an employee lands a big client, don’t just say “Congratulations.” Ask for specifics about the meeting and how it happened. This will give you a greater appreciation for the employee and will give the employee a greater sense of accomplishment.

- Implement formal or informal controls that slow down decision making within the workplace. It’s difficult to consider others when constantly making snap decisions.

- Persist in your efforts to practice empathy in the workplace. Empathy is cognitively costly. It might not come easily.

Remote Work and Empathy Success Stories

- Dell Technologies created a remote work program called Connected Workplace. In testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, Mark Pringle, Dell’s senior vice president of corporate real estate and global facilities, stated, “Connected Workplace allows our employees to choose the work style that best fulfills their needs on the job and in life in a highly mobile, collaborative, and flexible work setting. The program has positively impacted our business, our approach to talent acquisition, and our environmental footprint. But more than just a policy, this program is about a change in how we think about work—where work is not anchored to one place and time and instead is focused on outcomes.” One aspect of the program that Pringle attributes its success to is that “We trust our team members, and we want them to feel empowered.”

- Deloitte created a “flexibility and predictability initiative” that allows managers and employees to remain flexible in their work structure while working together as a team. This, along with other initiatives, has earned Deloitte numerous workplace and diversity recognitions—it was named to Fortune’s 100 Best Places to Work For and Consulting Magazine’s Top 10 Best Companies to Work For lists and was ranked No. 1 on BusinessWeek’s 2009 Best Places to Launch a Career list. In Deloitte’s “Working remotely: setting your team up for success,” the first suggestion to set up a remote team for success is to show empathy.

- Automattic, the company that created WordPress, is another company that has embraced remote work. According to Business Insider, nearly all of the company’s approximately 190 employees work from home, scattered across 141 cities and 28 countries. The company uses the cost savings from having a remote workforce to improve workplace morale and empathy among employees by creating “an awesome culture filled with company paid-for travel to exotic locations and other perks.” In particular, Automattic pays for an all-company “Grand Meetup” in exciting locations each year to ensure employees have a sense of belonging.

- Elsevier, the global information analytics and publishing business, was recognized by Comparably for ensuring its remote workers remained committed to the company culture. As highlighted in Comparably’s article, “How 5 Companies Keep Their Remote Workers Rooted in Company Culture,” Elsevier’s employees in China immediately moved to work from home when the company realized the implication of the pandemic in January 2020, and all the company’s staff were encouraged to work from home by March 2020. Elsevier “took an empathetic and pragmatic approach in supporting its people and its customers and rapidly harnessed technology to work from home,” which strengthened its culture and reminded employees of its mission and purpose.

February 2022