Management accountants use financial and other nontraditional data to not only help companies make better and more accurate decisions but also guide the senior management team and communicate business activities to a wide set of stakeholders inside and outside the organization, including regulatory bodies. Sustainability information represents another nontraditional data set to include in the data streams, and management accountants need to take a leadership role in ensuring that financial and nonfinancial data is fit for purpose. In this context, it’s important for finance and accounting professionals to assess the degree of fitness within a digital reporting environment to secure timely, auditable data for risk assessments, compliance, and scenario analysis.

Corporate sustainability strategy as well as new and emerging regulatory compliance reporting mandates have the potential to boost the strategic role of forward-thinking management accounting professionals. This is simply because companies’ C-suite, board of directors, and various stakeholders are proactively keeping an eye on more than just the company’s bottom line. In addition, sustainability is firmly on the agenda of global policy makers, meaning companies are being exposed to even more disclosure requirements from regulations.

The Paris Agreement (an international climate-change treaty) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development represent objectives integrated with a broader set of salient impacts and corporate risks. The International Labour Organization (ILO) Conventions, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights collectively represent policy priorities that align with globally agreed-upon goals and business governance standards. These are collectively designed to advance sustainable economies by addressing the impacts of business on society and the environment. Corporate sustainability and the transition to a low-carbon, more resource-efficient, and circular economy are keys to ensuring the long-term competitiveness and viability of the modern economy.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) or responsible business conduct (RBC) organizational strategies, new regulatory reporting requirements, and climate change, therefore, have quickly become defining issues of our time. The “new normal” is characterized by rising stakeholder expectations for companies to factor in sustainability goals; climate risk; and other environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics into their long-term strategic planning. In this new environment of increasing scrutiny from stakeholders and regulators, we need timely, auditable, machine-readable data to meet all of our organization’s needs and responsibilities.

THE DATA CHALLENGE

Every day, we create trillions of data points, from clicks on our mobile phones to creating documents in the cloud. According to IDC Global, the world generated 64.2 zettabytes of data in 2020 alone. This staggering number reflects what IDC calls the “unusually high” growth of data as millions of us adjusted to working from home during the pandemic. Although sustainability data is but a fraction of that growth, the reality is that storing, searching, and analyzing sustainability reporting data is a daunting task for the profession. While the flow of data is never-ending, managing it effectively and analyzing and interpreting it adeptly are crucial to the success of all sustainable businesses.

The average business can’t afford—and thus doesn’t have access to—sustainability data flows in a useful, comparable, machine-readable format that lends itself to reliable, data-driven decision making and a matching accountability model. To add to the complexity, some data necessary for assessing risks related to climate change and other sustainability topics doesn’t exist. In other cases, it exists but is out of reach, locked in external private repositories or siloed data vaults such as local hard drives. And some of the relevant data is available but may not be suitable to be machine-readable in a timely manner. The existing data and regulatory fragmentation carries high data management costs for organizations—money that could be better spent on impactful sustainable initiatives.

According to the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) and Business at OECD (BIAC), the cost of regulatory divergence (defined as inconsistent financial-sector regulation between different jurisdictions) is estimated to cost the global economy $780 billion per year. Further, in a study commissioned by Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2), the incremental compliance costs for the financial sector across 11 European Union (EU) member states between 2009 and 2017 was €4 billion ($4.52 billion). This is a staggering average of 2% to 4% of an organization’s total operating costs and a 610% cost increase over this eight-year period. The Data Warehousing Institute (TDWI) found that data quality problems cost U.S. businesses more than $600 billion annually. Think about what we could collectively do with that amount of money if we could spend it on positive-impact projects.

Bad data leads to bad decision making, and this impacts the company and, by extension, its entire supply chain. IBM estimated that bad data costs the U.S. economy approximately $3.1 trillion each year. Additional research from Experian found that bad data has a direct impact on the bottom line of 88% of American companies, with the average company losing around 12% of its total annual revenue.

It isn’t merely the cost of managing the data that’s an issue. The data quality isn’t up to par, either. Data quality is a key issue discussed in the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB) 2020 report, Falling short? Why environmental and climate-related disclosures under the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive must improve, which analyzed the 2019 environmental and climate-related disclosures of Europe’s 50 largest listed companies with a combined market capitalization of $4.3 trillion. The report demonstrated that these companies report data that lacks quality, comparability, coherence, and easy access. This lack of comparability across companies is primarily the result of a lack of a common reporting framework combined with companies’ freedom to mix and match standards, metrics, and frameworks when producing their sustainability disclosures.

Balancing the organizational challenges with user experience creates a surprising outcome. The European Commission determined that information users have equal difficulty locating, consuming, and analyzing sustainability information that companies reported, in part because the information isn’t sufficiently digitized and easily accessible. The implication is that no one is happy with the sustainability information ecosystem’s status quo.

MOVING TOWARD STRUCTURED DIGITIZATION

Momentum is building worldwide for companies and their stakeholders to reduce ESG information silos, fragmented or duplicative reporting requirements, the costs of data management, and the lack of trust in the data. Many global policy makers are focused on getting comparable companies’ (or reporting entities’) sustainability disclosures, metrics, and measurements into the market using multiple lenses. Additionally, a growing number of regulators and standard setters are starting to actively think about digital outcomes from the outset.

For instance, in February 2021, the European Lab Project Task Force on Non-Financial Reporting Standards (PTF-NFRS) published a report, Proposals for a Relevant and Dynamic EU Sustainability Reporting Standard-Setting, that reflected a cumulative and intensive effort that built on several of the specific findings in the IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) research paper A Digital Transformation Brief: Business Reporting in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which we wrote along with Tanuj Agarwal, Deborah Leipziger, Urmish Mehta, and Dermot Murray. The PTF-NFRS report detailed 54 recommendations for sustainable development and sustainable finance policies. Three of the report’s key points are that the standards must:

- Improve the quality of sustainability reporting in terms of structure and presentation;

- Ensure that sustainability information is widely and fully accessible; and

- Ensure that information is digitized such that it’s both machine-readable and human-readable.

The report considers elements beyond the legislative level. The PTF-NFRS report recommended that EU standards should, from the outset, provide a clear sustainability reporting structure and an underlying digital taxonomy that allow for agile access and analysis. In April 2021, the European Commission adopted a legislative proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which will oblige affected companies to report in compliance with European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). Europe is addressing financial and sustainability information access and digitization through a legislative act to establish a European Single Access Point (ESAP) for company-reported information.

On November 3, 2021—hailed as a landmark day for accounting by Reuters—the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation announced that it would complete the consolidation of the CDSB and the Value Reporting Foundation (VRF) as part of the new International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). The ISSB aims to develop a comprehensive global baseline of high-quality sustainability disclosure standards to meet investors’ information needs and serve the public interest. There’s renewed hope that we can move toward harmonized, comparable, worldwide sustainability standards with local customization, creating space for national legislatures to go further with their ESG ambitions.

Despite some cause for cautious optimism, there’s the genuine risk that efforts to solve the problem of creating a digital, standardized sustainability information flow from the cradle to the grave remain siloed unless all stakeholders take a holistic worldwide perspective.

CURRENT DATA-FLOW LANDSCAPE

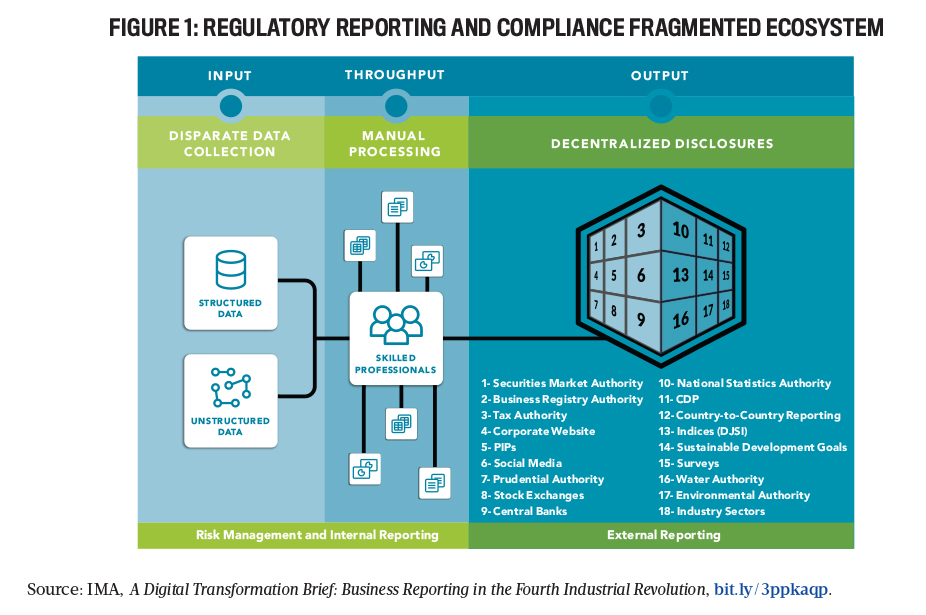

Digital transformation of sustainability information flows and data management has gained strategic significance as a critical capability for the management accounting profession. If we want stakeholders to trust the data that they use and analyze every day, then we need data that’s machine-readable, understandable, auditable, and accessible. Stakeholders are counting on forward-thinking management accounting professionals to help fix the information gap. A Digital Transformation Brief: Business Reporting in the Fourth Industrial Revolution examines this issue in detail and provides a visual depiction of the real challenges we need to collectively solve to meet stakeholder needs (see Figure 1).

The sustainability information flows and interfaces between input, throughput, and output across various systems aren’t universally aligned, often requiring human intervention to reprocess the output of one system into the format that’s necessary for the next system. The data is then connected to multiple output reports, increasing the importance of a single source of data truth. For example, the data from a regulated entity’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) software needs to be compiled and repackaged (i.e., throughput) in order to meet a regulator’s form and data-format (i.e., output) requirements for filing submissions. Seamless integration between these internal and external interfaces depends on codified standards for data generation, validation, and sharing.

These are the most common areas of fragmentation, but not the only ones. Different regulators require the same information in their specific formats or data types, requiring duplicative efforts. Some regulators request the same information in different forms and formats, mandating costly efforts with no real incremental value to the company or any of its stakeholders. The process of assembling, dismantling, and repackaging data in various required formats can cause compliance issues and unintentional information errors during regulatory filing. Adoption of common codified standards for machine-readable data creation and exchange across all stakeholders within the global compliance ecosystem could result in a giant leap toward coherence in information data flows worldwide.

Both businesses and regulators adopt unique standards, data definitions, and business validation rules for similar sustainability data elements and metrics. In addition to the cost factor, this lack of cohesion weakens the auditability of ESG information ultimately disseminated to a multitude of regulators and increases risks due to increased subjectivity, differences in interpretations, misinformation, and inadvertent partial compliance or noncompliance. Differences in regulatory information submission processes create additional hurdles in creating standardized last-mile reporting validation rules and seamless integration across internal and external systems. These regulatory differences all add to the complexity and costs of compliance.

Upstream data issues also exacerbate information-flow issues. For example, sustainability data definitions aren’t globally agreed upon. We don’t have a controlled vocabulary governing sustainability terms, references, or metrics. This fragmentation is a challenge when reporting the same information to multiple regulators because there’s a lack of clarity in communication and no single set of standards and definitions that’s usable across multiple regulators. It isn’t uncommon to find differences in the definitions of various data elements among regulators. This naturally lends itself to an increased risk of misstatement and miscommunication, in addition to the increased compliance costs of maintaining multiple variants of the same data items for entities having to validate the accuracy of their report each time they submit a regulatory filing.

The list of differences continues, including a lack of clarity in the terminology used in relevant national laws and regulations, which leaves so much open for interpretation. Other hurdles include the lack of common, standardized, agreed-upon metrics and companies’ inconsistent transposition, translation, and implementation of regulations. This fragmentation reflects confusion within organizations as well, with varying levels of maturity of the reporting group, including assigned responsibilities, control systems, people, and processes.

GLOBAL COOPERATION FOR DIGITIZATION

International cooperation will be key in developing the common comparable global standards that the marketplace needs. The global financial markets are already calling on regulatory authorities and sustainability standards boards to define common standards so that sustainable impact investment markets can continue to mature.

The need for greater international cooperation doesn’t stop there. We’re involved in an effort called the Impact Management Project (whose name is transitioning to the Capitals Coalition) aimed at facilitating a worldwide effort supported byTipping Point Fund for Impact Investing to bring together various ecosystem stakeholders to build consensus on how to address and reduce the friction within and between information flows. Check out this public-good site and get involved in this cutting-edge, unprecedented global collaboration. Armed with an understanding of ecosystem challenges and data issues, management accounting and finance professionals need to prepare to lead their organization through this seismic shift in our world of work.

PRIME OPPORTUNITY FOR MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANTS

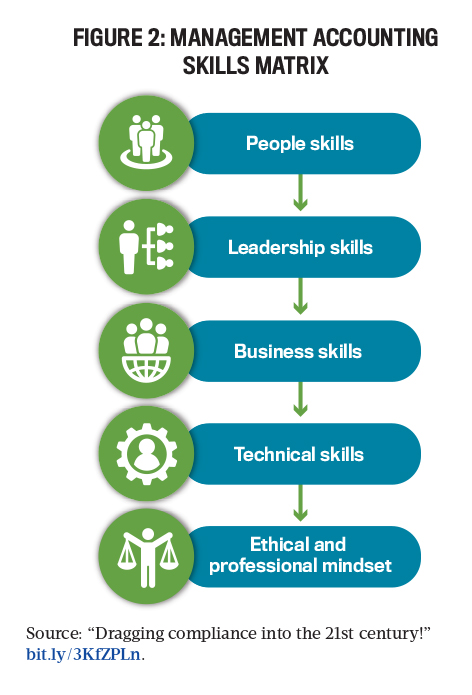

This digital transformation of businesses’ handling of data requires new and improved professional skills. Knowledge of the intersection of people, processes, and technology has never been more important in shaping the capabilities that the accounting and finance profession needs for achieving success.

Three key areas quickly emerge as cornerstones in this conversation: digital literacy, communication proficiency, and data science. In addition, the traditional capabilities and focus areas such as leadership, ethics, and accounting proficiency remain essential.

- The American Library Association’s (ALA) Digital Literacy Task Force defines digital literacy as:

- Technical and cognitive skills to locate, create, understand, analyze, and communicate a coherent story based on data;

- An ability to leverage a variety of technologies to manage data, including assessing its quality and value;

- Managing the legal, privacy, security, and stewardship of data; and

- Using these skills as a vehicle to promote discourse and engagement with a wide variety of stakeholders.

For finance professionals, digital literacy means being savvy with new digital tools and data management, understanding how they can be leveraged to extract, analyze, visualize, and report information (i.e., data science) with which we successfully tell an accurate, compelling story (i.e., communication proficiency). This is only achievable when we adopt a continuous-learning mindset, identify new ways of working with technology and data, and adapt our communications to bridge the gap between traditional and new digital methods of data management.

Considering potential paths to achieving sustainability goals, the applications of capability improvement become clearer. For instance, when we consider the renewed focus on resource efficiency, we need to be able to:

- Develop and build resource-efficient business models that generate greater benefits to the organization and its stakeholders—particularly in anticipation of new sustainable economy regulations as a way to get a head start on peers;

- Identify, measure, and report on the organization’s carbon footprint and other natural environmental matters to reduce reporting friction;

- Support new technologies, products, and processes that increase resource efficiency; and

- Communicate how resource efficiencies are reflected within the organization’s carbon-footprint-reduction success story in a way that stakeholders can trust, understand, and connect with. Communication is a critical skill that we must strengthen within our toolbox of capabilities.

Extending this line of thinking to consider climate resiliency in business, it requires skills in:

- Science and technology to support modeling and interpreting climate-change projections;

- Conducting risk-management assessments, such as projecting future availability of input materials and resources (i.e., minerals or metals);

- Illustrating and sharing ambitious, yet achievable, carbon-footprint-reduction plans; and

- Data governance by ensuring that quality data is fit for purpose from the outset and throughout the life cycle of information flows.

An important realization in sustainable economies and businesses is that our own professional capabilities, preparation, and investment are decisive factors that enable (or don’t) the “green transition” to sustainability and carbon neutrality from the outset, rather than merely resulting from the transition.

Associations have traditionally focused on core technical and professional skills development, but the new curriculum must include deeper skills development in sustainable business practices, leadership, and data analytics, empowering us to influence and persuade decision makers (see Figure 2). Organizations need personnel with these skills to transition quickly from their traditional business models to sustainable ones. It’s a matter of business survival and, by extension for us, professional survival.

Are you ready for our sustainable business future? The challenges are vast and interesting, and the emerging solutions will be profession-changing. Just as spreadsheets transformed accounting from static reporting to more dynamic storytelling and projections to inform strategic planning, digitally transforming sustainability information will change the how and why of our professional roles and responsibilities. We’re in a prime position as trusted and impartial custodians of data, so let’s not waste this opportunity to rise to the challenge of extracting and delivering more insightful and meaningful value to the businesses we support, using fit-for-purpose data to do so while serving as sustainability advocates. The planet and our stakeholders are counting on us—there is no “Planet B.”

April 2022