The traditional annual planning and budgeting routines still employed at many companies today were invented more than 100 years ago. At the time, the underlying assumption was that the future can be planned for, and, with large, untapped markets, business success is mainly a matter of efficiency. Complexity would be managed by detailed planning of simplified tasks and tight control of their execution. This command-and-control (C&C) performance management concept was the source of great efficiency gains throughout the Industrial Revolution and beyond.

Today, markets are global and highly competitive. The acronym VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) is frequently used to describe today’s business environment. Organizations have been adapting to the new playing field. Lean approaches have become standard in manufacturing, the Scrum Framework is spreading in IT departments, and companies are increasingly experimenting with objectives and key results (OKRs) and other agile performance management practices. Nevertheless, most organizations still shy away from changing the entire C&C-based system.

In 2013, we founded the Hilti Lab for Integrated Performance Management at the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland, to inspire, understand, and learn from the transformation of the corporate performance management system at Hilti, a multinational company with more than 30,000 employees that supplies drilling and fastening solutions for the construction industry. The goal was to develop insights in the area of management control and inspire further corporate performance management innovations.

From those efforts and experiences, we have identified an alternative approach to financial target setting and incentives, as well as planning and coordinating activities, that adjusts to the needs of today’s dynamic and complex business environment. Rather than a C&C approach to performance management, it centers on a management principle of guided self-control. It affects the culture of an organization, drives organizational agility, and transforms the governance of an organization toward a model based on more self-control and self-organization guided only by a few strategic objectives and targets.

The practice-tested system change is guided by specific self-control building blocks that can be implemented in an evolutionary way that minimizes disruption within an organization. It’s an opportunity for the finance organization to position itself as a leader in the transformation of the entire corporate performance management system.

PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT IN A VUCA ENVIRONMENT

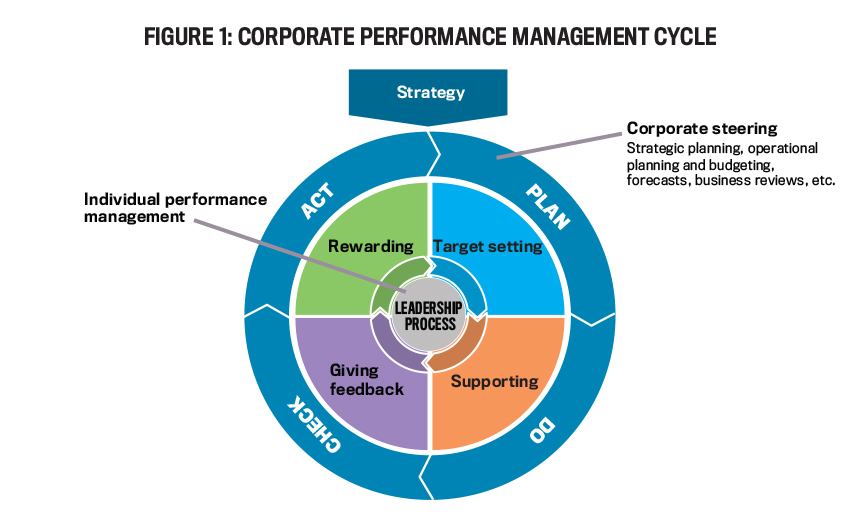

Corporate performance management is a complex and abstract discipline. In practice, the term “performance management” is frequently associated with the individual leadership process or IT support of the management process. The ideal form is typically described as an iterative cycle of target setting, giving support and feedback, and rewarding through individual bonuses for target achievement, which emphasizes a pay-for-performance approach.

On the corporate level, the steering process is often described with the help of William Deming’s Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. A strategy guides the planning process. The strategy execution is orchestrated by the annual planning and budgeting process, which breaks the strategy down into measurable targets and actionable initiatives. Forecasting and business review routines ensure the checking and adjustment during the year.

Click on any image to enlarge.

While the general steps make sense, the problem is that the application follows a C&C pattern built on the following assumptions (see Figure 1):

- The future is plannable; therefore, it’s clear how to get to the target.

- A plan (budget) is a good yardstick for performance, and it’s possible to perfectly measure deviations to the plan.

- People are fully rational; therefore, carrots and sticks (rewards and punishment) work best in all situations.

- The supervisors (managers) are more knowledgeable about the tasks to be executed than the frontline, operationally responsible employees.

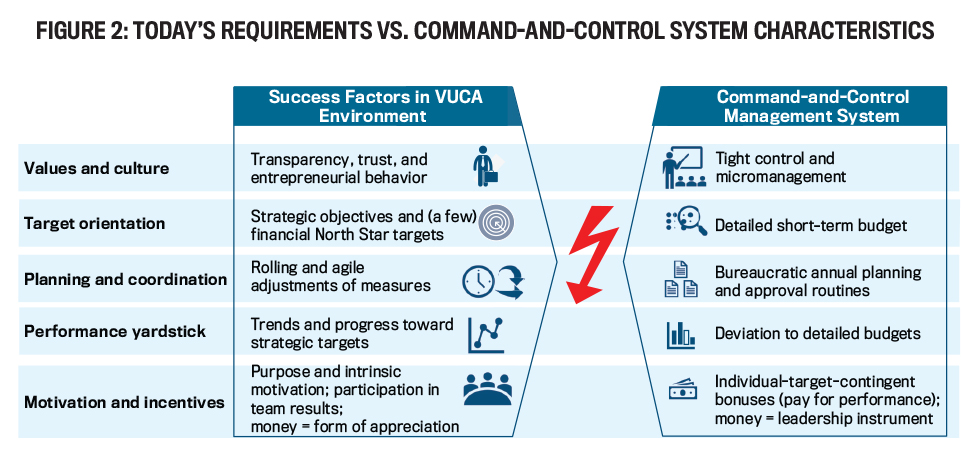

The assumptions were probably correct when this model of corporate performance management was established. Today, however, markets are much more competitive, and the environment is significantly more dynamic and complex. In a VUCA environment, the corporate performance management requirements change significantly (see Figure 2).

In an increasingly dynamic and complex environment, transparency, trust, and entrepreneurial behavior by empowered employees are far more effective than tight control and micromanagement. The guided self-control approach focuses on longer-term strategic objectives and a few relative financial targets (called “North Star” targets) to guide the company and its activities. These serve as a much better orientation and performance yardstick than short-term, detailed budgets that become increasingly obsolete as time passes.

Rather than planning, coordinating, and adjusting measures once a year, the adjustment of measures needs to be more agile and should be organized in an unbureaucratic, rolling process. The significantly more complex, knowledge-based tasks of today require a much stronger focus on intrinsic motivation and teamwork—hence, the need for greater emphasis on purpose and involvement. In addition, behavioral research, such as that from Paul Marciano (Carrots and Sticks Don’t Work, 2010), has produced compelling evidence that money (bonuses) for individual target achievement (i.e., carrot-and-stick principle) can be demotivating in the VUCA context. Bonuses should instead be used as a form of appreciation for team efforts (i.e., the participation principle).

BARRIERS TO CHANGE

C&C patterns are deeply embedded in many organizations. Heavy emphasis is still placed on top-down strategy development and execution processes. The assumption that an organization’s complexity can be summarized into one plan is still widespread.

Why do so many organizations maintain their C&C-based management systems given the changing business environment? We see three major barriers to change that reinforce each other:

- Lack of awareness of the problem. Change has always been around us, and the increasing pace of change is hard to recognize when you’re in the middle of it. It’s difficult to see the interdependencies inside a complex management control system and realize that the underlying assumptions of the existing management system are no longer applicable. It also isn’t transparent how much the system is slowing down the organization. There may be indicators like low employee engagement, tactical behavior, increasing bureaucracy, sandbagging, lack of growth, etc., but it isn’t obvious to relate this back to a system problem as a root cause. Therefore, the magnitude of the problem and the improvement potential, which go along with a system change, aren’t obvious.

- Complexity of the change. Those who get an idea of the need for a system change may shy away from making a change because of how complex the effort will be. To change toward more self-control and self-organization involves a paradigm shift at the top and at the bottom of the organization. Leadership roles change, so it involves the board of directors and senior leaders triggering a change that impacts their own roles. Moreover, employees must be ready to take on more responsibility. As a result, the motivation to make such a change to the organization either requires visionary thinking and courage or comes in response to pressure and pain—and sometimes both.

- Lack of awareness of alternative solutions. Those who see the problem and would have the courage to change may not be aware of alternatives. Methods like the Holacracy governance model (see Brian J. Robertson’s Holacracy: The Revolutionary Management System that Abolishes Hierarchy, 2015) are still little known and cater more to small, strongly knowledge-based business models. Other suggestions for a management model change, like the Beyond Budgeting model (Jeremy Hope and Robin Fraser, Beyond Budgeting: How Managers Can Break Free from the Annual Performance Trap, 2003), may be too generic to guide transformation efforts.

Given the dynamics in today’s environment and the complexity involved, there’s a clear need for more guidance on the available alternatives to a C&C performance management system and how such systems can be implemented.

AN INTEGRATED VIEW

Some organizations have seen the need for change and have begun to optimize parts of the system. Yet rarely do they change the entire system. When making these piecemeal changes, the risk is very high that the entire system may lose its effectiveness. Leadership and culture development efforts preaching purpose orientation, strong values, empowerment, and the supremacy of transformational leadership over transactional leadership aren’t compatible with traditional approaches to performance management, like tight budgeting. Employees experience these inconsistent change efforts as conflicting messages and often perceive them as hypocritical and cynical.

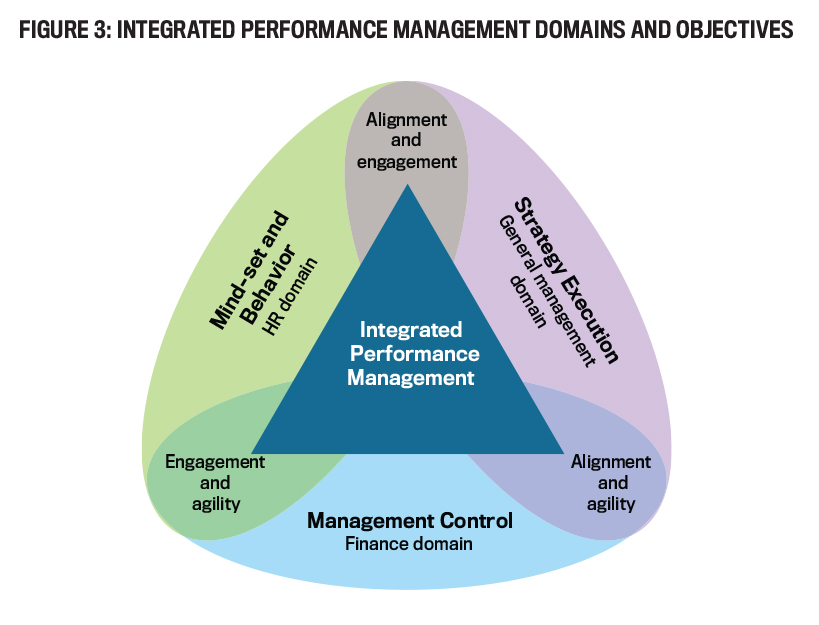

Transitioning out of a C&C system is a complex task that requires an integrated, holistic view and adjustments of practices in finance, HR, and general management (see Figure 3). To foster supportive behaviors, practices related to strategic and operational target setting and to motivation and coordination not only need to change, but they must be synchronized. Only an integrated design ensures that the parts of a new performance management system are fully synergetic and simultaneously drive alignment, engagement, and agility.

GUIDED SELF-CONTROL

The key to adopting a much more self-controlled way of managing performance without having to make radical organizational changes is to find the sweet spot between the very tight C&C system and a very loose system of complete self-organization and self-control. We call this sweet spot the “guided self-control management system.”

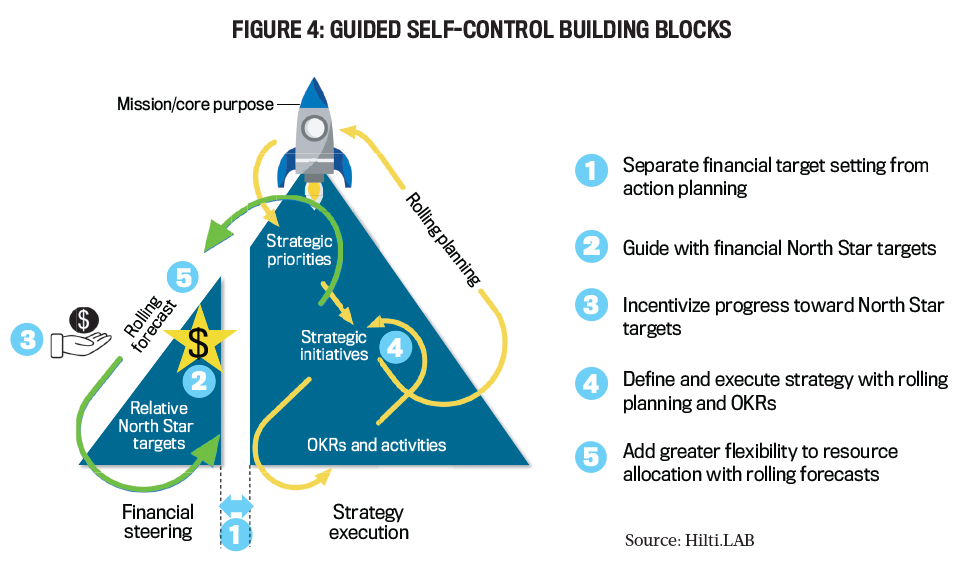

The key characteristic of guided self-control is that the organization still has top-down direction through strategic targets and strategic initiatives, like in a C&C model. But the way those targets and initiatives are formulated and translated throughout the organization ensures that they function as guidelines and remain at a high, broad level so that self-control and self-regulation can take place further down the organization’s structure. Our application experience shows that the principle can be brought to life with five guided self-control building blocks (see Figure 4).

Building Block 1: Separate financial target setting from action planning. In the C&C management system, financial targets are combined with initiatives and tasks that lead to one total plan for the organization: the budget. It documents a complete horizontal and vertical alignment of the organization based on the assumption that the target and the path to get there can be planned. In today’s complex and dynamic environment, the path toward a desired outcome is frequently too complex to be planned for in all details up front. It’s rather the result of an iterative trial-and-error process.

The first step away from the C&C steering system is to recognize this systemic problem and consciously separate the financial target setting from the planning of initiatives and action plans to achieve those targets—and thus developing separate instruments for the different functions (motivation, coordination, and prognosis).

Setting financial targets as a source of orientation becomes even more important in a VUCA business environment, not less so. To make it meaningful, however, target setting should be done more strategically on a higher, aggregated level and in relative form, as we’ll see with building block 2. The planning of initiatives and actions should follow a much more decentralized, self-organized process with frequent reflections of progress, which needs to be coordinated, but not with the unrealistic expectation to fit everything into the one annual number of a budget.

Building Block 2: Guide with financial North Star targets. In a dynamic and complex environment, detailed annual budget targets can provide a false sense of security and are the wrong yardstick for performance. It’s much more effective and meaningful to have relative strategic targets for a few key performance drivers of the company’s business model.

Growth, profitability, and capital efficiency are the three generally applicable drivers of financial value creation. Our suggestion is to set targets in a relative form derived from the strategy of the organization. In this context, “relative” means relative to an external or internal benchmark and in the form of output/input ratios like return on sales (ROS) or efficiency and productivity ratios. That way, much like the North Star served as a fixed point that sailors would use to help navigate and remain on course, these targets would help the organization stay oriented to the proper strategic direction in a volatile environment—hence the term.

For sales growth targets, for example, an organization defines a benchmark target in the form of a growth target factor relative to the relevant market. For example, a growth target factor of 1.5 means that, for (assumed) market growth of 2% per year, the sales growth target is 3% per year (1.5 times 2%). This factor is derived from the organization’s strategy that defines what relative market share or market position the organization or business unit wants to achieve. The growth targets move up or down with the movement of the market, but the relative ambition stays fixed, like the North Star.

Other organizations use an established peer group as a benchmark and set growth target factors relative to that group’s sales growth. Targets are set for the future based on the assumptions for the market/peer-group growth, and performance is measured retrospectively, depending on the actual growth of the relevant market or peer group.

Organizations that don’t have access to good market or peer group data simply use percent-based average annual growth targets (typically derived from compound annual growth rates) that reflect management’s opinion on the growth potential of the business model given the current strategy. These relative targets are usually derived from a strategic planning exercise reflecting on relative market share/position and the respective strategic ambition.

Examples of North Star targets for the profitability and capital efficiency targets could be ROS or capital turn targets (capital employed divided by net sales). Service centers like manufacturing plants set strategic North Star targets in the form of output/input improvement ratios (i.e., annual productivity of x%).

In this way, North Star targets are set for all main organizational units—the profit, service, and cost centers of an organization—for the one or two essential growth, profitability, and (where applicable) capital efficiency outcome key performance indicators. At the same time, the measurement system is adjusted. Instead of comparing financial results of budget vs. actual, the organization measures the rolling 12-month trends of the strategic gap, i.e., the comparison of actual results compared to the North Star target.

In many cases, using North Star targets and tracking the development of the strategic gap provide sufficient guidance for steering purposes. The annual target-setting routines of a budgeting process and the midterm financial planning exercise become redundant.

Since North Star targets are valid for an unspecific time period, the targets are only changed when external or internal events change the assessment on the strategic potential of an organization or business unit. This usually happens only in the case of structural changes, such as a major merger or acquisition, or other major strategic moves that lead to changes in the organization’s business model.

Major external impacts, like the financial crisis in 2008-2009, can also trigger changes. But it depends on the event. In most organizations already applying this concept, the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t lead to a change of targets. Businesses recovered better than initially expected, and the organizations’ longer-term potential assessments therefore didn’t change. This is a good example for how relative North Star targets keep their relevance in a volatile environment.

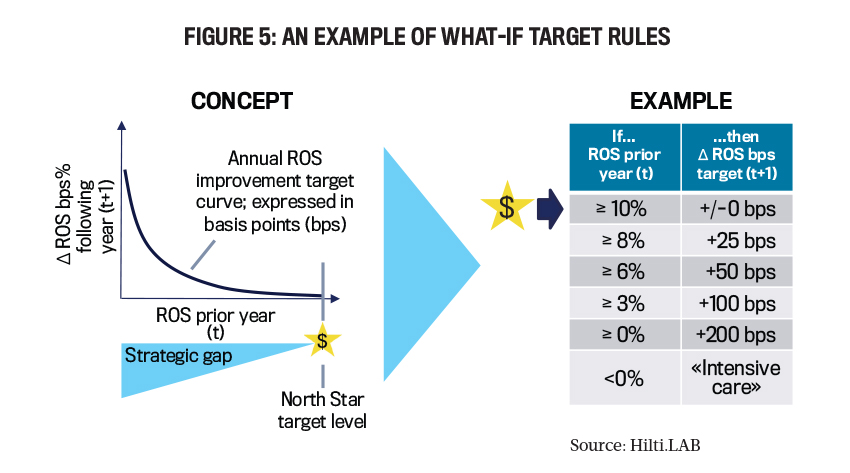

In larger organizations with many units and diverging performance levels, the guidance from North Star targets can be enhanced with “what-if rules” for more specific annual target guidance. The rule is simple. The bigger the strategic gap of a unit’s prior-year performance, the more improvement is required in the following year. With such rules, the North Star target system enables self-regulated portfolio steering, an extremely simple and powerful way of strategic guidance in a larger organization. Figure 5 illustrates an example for a “what-if rule” for ROS targets.

This concept not only provides more stable and meaningful guidance in a dynamic environment, but it also institutionalizes the separation of target setting and motivation from the coordination function, which enables more self-control with a significant positive impact on entrepreneurial behavior in an organization. It systematically improves the alignment of an organization with its strategy and with the objectives of shareholders and investors. Information requests from potential creditors and investors, who still may require the traditional annual budget information, can be equally well (if not better) satisfied with the most recent forecast (see building block 5).

Building Block 3: Incentivize progress toward North Star targets. C&C organizations rely heavily on variable compensation elements (bonuses) linked to individual targets. As noted earlier, research and experts in the field of incentive design suggest that money in today’s more complex task environment shouldn’t be instrumentalized as a reward for individual target achievement but rather be used as an (important) form of appreciation by sharing the success of the entire team. This can be done very effectively by unlinking the bonus calculation from individual targets and linking it instead to the progress of an organization (or business unit) toward the longer-range North Star targets, i.e., linking individual bonuses to the development of the strategic gap of an organization or unit.

Dropping individual target bonuses is a hotly debated issue within many companies that set out to implement this new approach, as it touches a fundamental paradigm shift away from a C&C philosophy in management. Yet our experience regularly shows that the initial concerns regarding this change aren’t justified. If the change is implemented in a fair way, it leads to a significant simplification and to a much better alignment of employee, management, and shareholder interests. It’s another important self-control building block that further strengthens the relevance of the relative North Star targets.

Building Block 4: Define and execute strategy with rolling planning and OKRs. Now that the entire organization and its major responsibility centers are aligned with the strategy through the North Star targets, no more energy and time needs to be wasted on annual target-setting exercises. The entire focus and energy of an organization can be put on the main performance lever: the planning and execution of strategic initiatives and activities.

The separation from financial target setting opens up much more room for more frequent, flexible, and self-organized planning processes. This context is a perfect fit for the utilization of more agile alignment and engagement methods like OKRs, which can replace the traditional annual management-by-objectives methods and drive much more bottom-up involvement in the planning and execution process of initiatives, an extremely critical element for intrinsic motivation, innovation, and agility.

Building Block 5: Add greater flexibility to resource allocation with rolling forecasts. A rolling forecast process forms the final building block for guided self-control. Typically, rolling forecasts take place in a three-to-four-month cycle synchronized with the rolling planning process of building block 4. The rolling forecast ensures a coordinated and flexible resource allocation process.

The rolling forecast isn’t the basis for future targets, so tactical considerations don’t influence the prognosis. The target setting is already covered by the North Star target system. In this setting, the rolling forecast is an instrument to manage and steer fixed costs in corporate functions. This is similar in principle to a budgeting process, but with the advantage that resource allocation decisions can be done regularly throughout the year, not just on an annual basis. Also, organizations that need a formal budget for other stakeholders, like creditors, can easily use the rolling forecast as a “formal synonym” for the budget. Experience shows that it regularly provides even better—i.e., less tactically loaded—information than the traditional budget.

Separating out the target-setting function through the use of North Star targets creates the perfect conditions for positioning the rolling forecast as an instrument purely for prognosis and coordination. In contrast, if the rolling forecast is implemented on top of a traditional budget approach, as is done frequently, the rolling forecast is regularly perceived as more, rather than less, command and control. It continues to be the basis for future budgets and, therefore, systematically triggers tactical behavior. For this reason, it’s no surprise that the rolling forecast is unfortunately already “burned” in quite a few organizations.

FOCUS ON STRATEGY

In the traditional C&C system, the annual budget number is the central yardstick for performance evaluation. In the guided self-control system, the strategy, represented by the relative North Star targets, becomes the central yardstick for performance evaluation—not just in the strategic planning and review session, but also for day-to-day operational steering.

Strategic planning and operational steering processes seamlessly merge into one integrated process. Continuous improvement and closing the gap toward the North Star targets become the main focus. Having more consistent targets as well as the constant monitoring of actual trends both lead to significantly higher levels of transparency about the organization’s performance. With the implementation of the five guided self-control building blocks, the traditional budget processes become obsolete. All of the functions of the budget process are covered with more flexible methods.

All in all, our experiences have shown that the implementation of the building blocks transforms an organization’s management control system. The approach exerts a strong influence on the behavior of team leaders and team members, thereby systematically driving the culture of an organization toward more entrepreneurial behavior. It systematically supports alignment, engagement, and organizational agility as an outcome. And with that comes greater growth and innovation in the long run. The finance organization can be the trigger for this transformation and thereby position itself as a strong business partner in the company.

October 2021