Critical thinking is needed to evaluate complex situations and arrive at logical, sometimes creative, answers to questions. Informed judgments incorporating the ever-increasing amount of data available are essential for decision making and strategic planning.

Thus, creatively thinking about problems is a core competency for accounting and finance professionals—and one that can be enhanced through effective training. One such approach is through metacognition. Training that employs a combination of both creative problem solving (divergent thinking) and convergence on a single solution (convergent thinking) can lead financial professionals to create and choose the best interpretations for phenomena observed and how to best utilize the information going forward. Employees at any level in the organization, from newly hired staff to those in the executive ranks, can use metacognition to improve their critical assessment of results when analyzing data.

THINKING ABOUT THINKING

Metacognition refers to individuals’ ability to be aware, understand, and purposefully guide how to think about a problem (see “What Is Metacognition?”). It’s also been described as “thinking about thinking” or “knowing about knowing” and can lead to a more careful and focused analysis of information. Metacognition can be thought about broadly as a way to improve critical thinking and problem solving.

In their article “Training Auditors to Perform Analytical Procedures Using Metacognitive Skills,” R. David Plumlee, Brett Rixom, and Andrew Rosman evaluated how different types of thinking can be applied to a variety of problems, such as the results of analytical procedures, and how those types of thinking can help auditors arrive at the correct explanation for unexpected results that were found (The Accounting Review, January 2015). The training methods they describe in their study, based on the psychological research examining metacognition, focus on applying divergent and convergent thinking.

While they employed settings most commonly encountered by staff in an audit firm, their approach didn’t focus on methods used solely by public accountants. Therefore, the results can be generalized to professionals who work with all types of financial and nonfinancial data. It’s particularly helpful for those conducting data analysis.

Their approach involved a sequential process of divergent thinking followed by convergent thinking. Divergent thinking refers to creating multiple reasons about what could be causing the surprising or unusual patterns encountered when analyzing data before a definitive rationale is used to inform what actions to take or strategy to use. Here’s an example of divergent thinking:

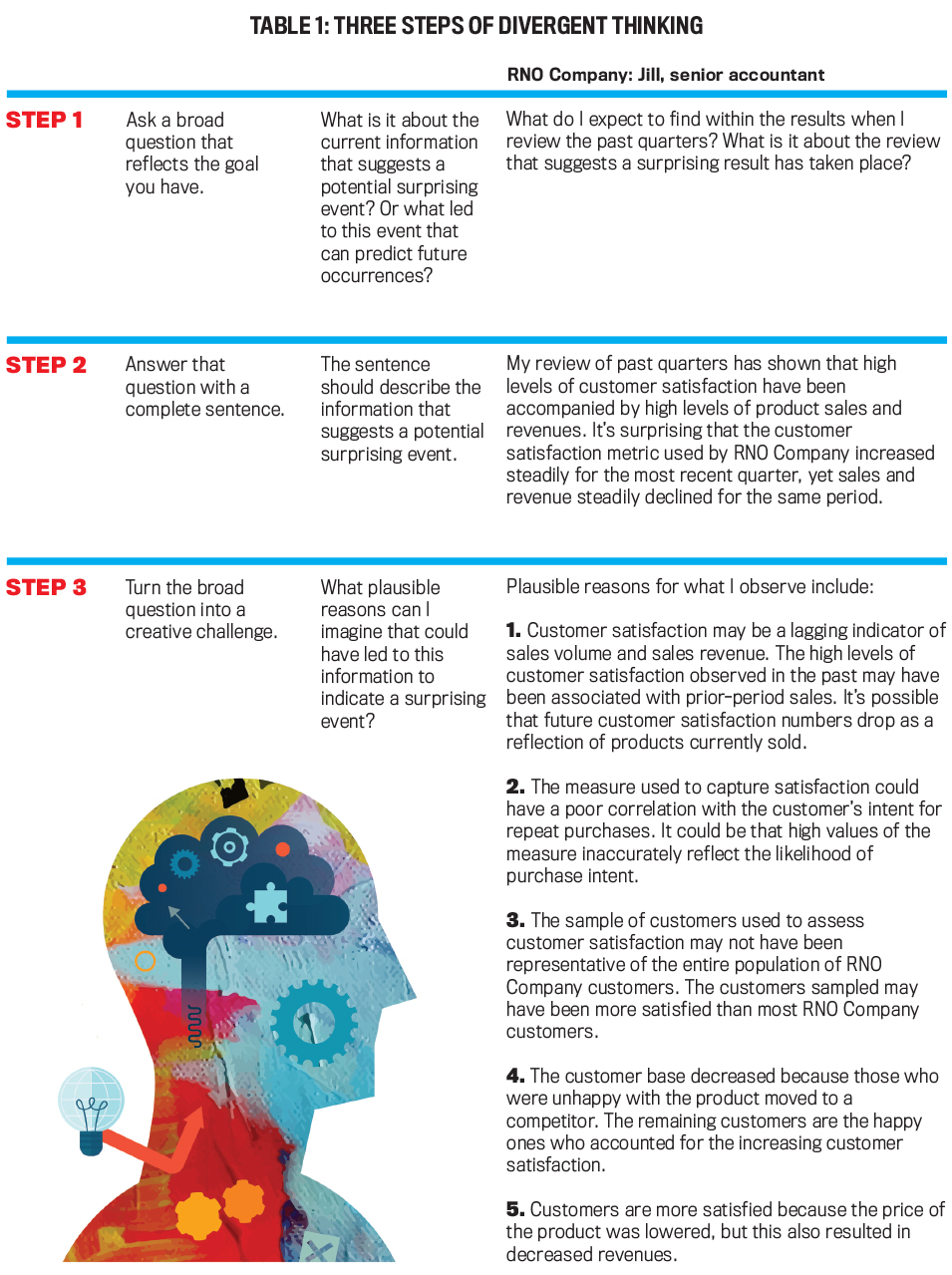

The customer satisfaction metric employed by RNO Company has increased steadily for the quarter, yet its sales numbers and revenue have declined steadily for the same period. Jill, a senior accountant, conducted ratio and trend analyses and found some of the results to be unusual. To apply divergent thinking, Jill would think of multiple potential reasons for this surprising result before removing any reason from consideration.

Convergent thinking is the process of finding the best explanation for the surprising results so that potential actions can be explored accordingly. The process consists of narrowing down the different reasons by ensuring the only reasons that are kept for consideration are ones that explain all of the surprising patterns seen in the results without explaining more than what is needed. In this way, actions can be taken to address the heart of any problems found instead of just the symptoms. On the other hand, if the surprising result is beneficial to an organization, it can make it easier to take the correct actions to replicate the benefit in other aspects of the business. Here’s an example of convergent thinking:

Washoe, Inc.’s customer satisfaction metric has increased steadily for the quarter, yet sales numbers and revenue have steadily declined for the same period. Roberto found this result to be surprising. After employing divergent thinking to identify 10 potential reasons for this result, such as “the reason that customers seem more satisfied is that the price of goods has been reduced, which also explains the reduction in sales revenue.” To apply convergent thinking, Roberto reviewed each reason that best fit. If the reason doesn’t explain the unusual results satisfactorily, then it will either be modified or discarded. For example, the reduced price of goods doesn’t explain all of the results—specifically, the decrease in units sold—so it needs to either be eliminated as a possible explanation or modified until it does explain all the results.

Exploring strategic or corrective actions based on reasons that completely explain the unusual results increases the chance of correctly addressing the actual issue behind the surprising result. Also, by making sure that the reason doesn’t contain extraneous details, unneeded actions can be avoided.

It’s important to note that a sequential process is required for these types of thinking to be most effective. When encountering a surprising or unexpected result during data analysis, accounting professionals must first focus strictly on divergent thinking—thinking about potential reasons—before using convergent thinking to choose a reason that best explains the surprising result. If convergent thinking is used before divergent thinking is completed, it can lead to reasons being picked simply because they came to mind right away.

LEARNING THE PROCESS

Improving divergent and convergent thinking can benefit employees at any level of an organization. Newer professionals who don’t have as much technical knowledge and experience to draw upon may be more likely to focus on the first explanation that comes to mind (“premature convergent thinking”) without fully considering all of the potential reasons for the surprising results. Experienced individuals such as CFOs and controllers have more technical knowledge and practical experience to rely on, but it’s possible these seasoned employees fall into habits and follow past patterns of thought without fully exploring potential causes for surprising results.

Instructing all accounting professionals on how to think about surprising results can help them have a more complete understanding of the issues at hand that will help guide actions taken in the future. It can lead to a more creative approach when analyzing information and ultimately to better problem solving.

When teaching employees to use divergent and convergent thinking, the goal is to get them to focus on what should be done once they identify information that suggests a surprising result has occurred. The first step is to learn how to properly use divergent thinking to create a set of plausible explanations more likely to contain the actual reason for the surprising results. There’s a three-step method that individuals can follow (see Table 1):

- Ask a broad question that reflects the goal you have: For instance, what is it about the current information that suggests a potential surprising event? Or what led to this event that can help predict future occurrences?

- Answer that question with a complete sentence: Be sure the answer includes a description of the information that suggests a potential surprising event.

- Turn the broad question into a creative challenge: Identify the plausible reasons that could have led to the indications of a surprising event.

Once employees have a good grasp of how to use divergent thinking, the next step is to instruct them in the proper use of convergent thinking, which involves choosing the best possible reason from the ones identified during the divergent thinking process. Potential reasons need to be narrowed down by removing or modifying those that either don’t fully explain the surprising results or that overexplain the results.

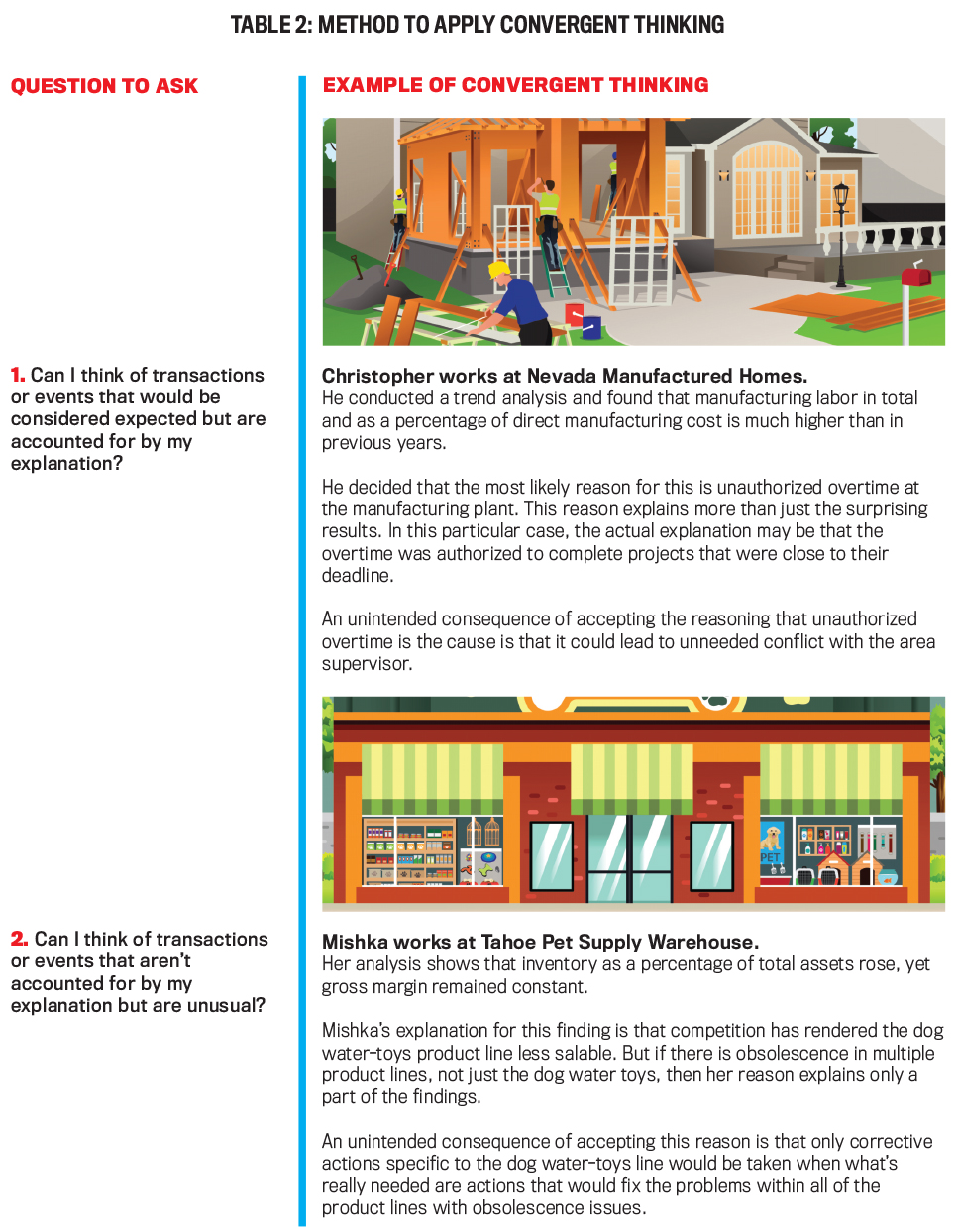

Two simple questions can help individuals screen each of the possible explanations generated in the divergent thinking process (see Table 2):

- Can I think of transactions or events that would be considered expected but are accounted for by my explanation?

- Can I think of transactions or events that aren’t accounted for by my explanation but are unusual?

The first question is designed for an individual to think about whether there are other events outside of the current issue that fit the explanation: “Does the explanation also address phenomena that aren’t related to or outside the scope of the surprising result that’s being studied?” If the answer is “yes,” then this is a case of overexplanation. Consider, for example, a scenario involving an increase in bad debts. Relaxing credit requirements may explain the increase, but they would also explain a growth in sales and falling employee morale due to working massive amounts of overtime to make products for sale.

The second question is designed to think about whether an explanation only accounts for part of the phenomenon being observed: “Does the explanation address only part of what’s being observed while leaving other important details unexplained?” If the answer is “yes,” then it’s an under-explanation. For example, consider a decline in sales. An economic downturn at the same time as the decline may be a possible explanation, but it might only be part of the problem. A drop in product quality or a drop in demand due to obsolescence could also be causing sales to decline.

If the answer to either screening question is “yes,” then the explanation needs to be discarded from consideration or modified to better address the concern. In the case of over-explanation, the reason is too general and may lead to action areas where none is needed while still not addressing the actual issue. For underexplanation, the reason is incomplete because it accounts for only a portion of the phenomenon observed, thus action may only address a symptom and not the actual root problem.

If the answer to both questions is “no,” then the explanation is viable. The chosen reason neither overexplains nor underexplains the issue at hand, making it more likely that the recommended solution or plan of action based on that reason will be more successful at addressing the actual cause of the issue.

Divergent and convergent thinking are two distinct processes that work in conjunction with each other to arrive at potential reasons for the results they observe. Yet, as previously noted, the two ways of thinking must be conducted separately and sequentially in order to obtain optimal results. Divergent thinking must be applied first in order to achieve a diverse set of potential reasons. This will maximize the probability of generating a feasible reason that explains the results correctly. After the set of potential reasons has been generated using the divergent thinking approach, convergent thinking should be used to methodically remove or modify the reasons that don’t fit with the surprising results.

If both divergent thinking and convergent thinking are done simultaneously, premature convergence can lead to a less-than-optimal reason being chosen, which may lead to taking the wrong course of action. Thus, it’s important with training to instruct employees in the use of both divergent thinking and convergent thinking and to use the types of thinking sequentially.

ORGANIZATIONAL TRAINING

Learning to apply divergent and convergent thinking can require a substantial time commitment. The process we’ve described here is designed to enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills. It outlines a general approach that doesn’t provide specific guidance on the best methods to analyze data or complete a task but rather focuses on successful methods to think of a diverse set of reasons for any surprising results and then how to choose the best explanation for that result in order to be able to recommend the most appropriate actions or solutions.

Individuals can practice the approach we’ve described on their own, but each organization will likely have its own preferred way to approach the analyses. Plumlee, et al., used training modules in their study that could be employed in a concerted effort by a company, with supervisors training their employees. We estimate that a basic training session would take about two hours. Complete training with practice and feedback would require about four hours—which could grow longer with even more for intensive training.

One area where this training could be very effective in helping employees is data analytics. In the past decade, an increasing amount of accounting and financial work involves or relies on data analysis. Data availability has increased exponentially, and companies use or have developed software that generates sophisticated analytical results.

Typical data analysis procedures accounting professionals might be called on to perform include things such as ratio and trend analyses, which compare financial and nonfinancial data over time and against industry information to examine whether results achieved are in line with expectations for strategic actions. Additionally, analyses are forward-looking when performance measures examined are leading indicators.

In order to perform data analytics effectively, accounting professionals must exercise sufficient judgment to critically assess the implications of any surprising results that are found. The quality of judgments and understanding the best ways to conduct and interpret the information uncovered by data analytics have typically been a function of time spent on the job along with training. At the same time, however, it’s commonplace that many of these analyses are performed by newer professionals.

Training in metacognition will help these employees more effectively and creatively reach conclusions about what they’ve observed in their analysis. Since the method discussed provides general instruction, each organization can customize the approach to best fit its own operations, strategies, and goals. Implementing a training program can be worth the investment given the importance of critical thinking throughout the process of evaluating operating results. Avoiding potential failures with interpreting results that could be prevented would seem to warrant the consideration of metacognitive training.

November 2021