David R. Koenig, founder of the Directors and Chief Risk Officers group (DCRO) and author of The Board Member’s Guide to Risk and Governance Reimagined, and Mark L. Frigo, cofounder of the Strategic Risk Management Lab in the Kellstadt Graduate School of Business at DePaul University, discuss how boards and executive teams can use life-cycle thinking and focus on managing firm risk as well as recognizing stakeholders as capital providers to enable companies to create long-term sustainable value.

Frigo: During our discussions on how to help boards of directors in risk governance, we identified two important and related themes from your work that would be very useful for CFOs and executive teams: (1) managing firm risk through innovation and (2) recognizing stakeholders as capital providers. Why are these two concepts so important in today’s environment?

Koenig: Let’s take firm risk and innovation first. Firm risk for many investors is a measure of how a company’s stock price has varied relative to an index or some peer group. That’s a backward-looking mind-set about risk when everything about risk should be forward-looking and anticipatory. Our research colleague Bartley J. Madden has done an excellent job of reframing the concept of firm risk as anything that stands in the way of a company achieving its goals or fulfilling its purpose. That’s genuinely forward-looking, which makes it a better way of thinking about risk in the context of why companies exist.

As you know, I contend that companies exist specifically to take risk. So they should be as good at taking risks—or managing firm risk—as they can be. Thinking about firm risk in the way Madden frames it is quite helpful in that regard. In his book, Value Creation Principles, Madden notes that firms create value when the return on their portfolio of ideas, people, and processes exceeds their cost of capital. This is akin to the notion of creating economic profit, a popular idea among management consultants, as you discussed in your article with Dominic Barton.

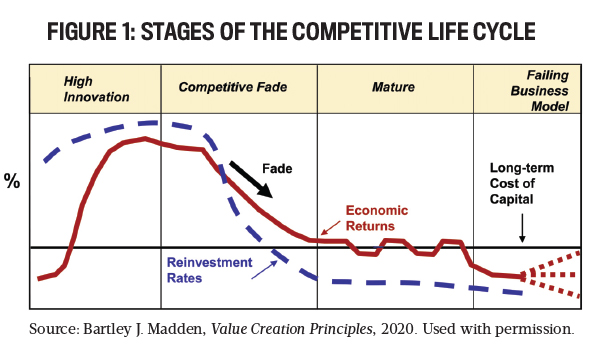

Madden highlights a life-cycle approach wherein value may be destroyed in the early phases (in the short term) of innovation as companies invest in new ideas, but value is rapidly created when some of those innovations realize their potential. That success attracts competitors, and in some cases, “internal complacency,” which can combine to whittle away the value created by that innovation. Madden and others call this concept “competitive fade.”

In Governance Reimagined, I describe a framework for governing complex systems like firms that’s ultimately about treating investments as a venture portfolio of various forms of capital—financial, for sure, but also intellectual, human, technological, reputational, and more, including something that I have written about more recently that’s akin to “freedom capital” or, as I refer to it, our “nested freedom” to pursue what we have the capacity to pursue. With a venture portfolio, you’re continually investing in new ideas and innovations, many of which will fail and destroy value. But suppose you’re very good at managing this portfolio. In that case, enough of these ideas and innovations will succeed in such big ways that the portfolio’s risk-adjusted return exceeds just about any other form of investment portfolio.

Now, in getting to stakeholders as capital providers, the idea of nested freedom is essential. Our freedom to pursue our goals and purpose—our capacity to create value—is determined by the complex interaction of all the entities that provide us with capital. They all want us to succeed in some manner and have some expectations or rules about utilizing their capital. The interaction of these rules and expectations creates a boundary (or nest) within which we’re completely free to pursue our goals, provided our actions don’t contradict their rules or expectations. That boundary isn’t stable and can shrink or expand based on our actions. The larger the “nest,” the more likely we’ll achieve our purpose.

Those that provide us with capital expect some kind of return. They have a stake in our success. Hence, we rightly refer to them as stakeholders. Because they play a role in defining our capacity to take risk and the boundary within which we’re free to take that risk, we rightly give them attention, even if not enough. Recognizing this capacity to take risks, bounded by the nest of expectations and rules, as a potential obstacle to achieving our purpose, ties the role of stakeholders as capital providers to Madden’s concept of firm risk.

Frigo: Now let’s turn to life-cycle thinking. Creating exceptional long-term sustainable value means achieving favorable fade as shown in the competitive life-cycle framework (see Figure 1), which has been explored in the DePaul Strategic Risk Management Lab.

Based on your work with boards and executive teams, how can CFOs help boards of directors to understand and conceptualize firm risk? (See “Firm Risk and Life-Cycle Reviews” at the end of this article.)

Koenig: It’s difficult to put this burden solely on the CFO. It’s a mind-set change that needs to be present in the executive suite and the boardroom, or no amount of reporting on the cost of capital or processes of identifying obstacles to success will matter. The CFO can expand and develop how the company thinks about capital to include all forms. Further, the CFO can provide boards with continual reporting on trends in the cost of those various forms of capital, especially relative to close substitutes in stakeholders’ eyes.

It’s important to remember that competitive fade is a function of both returns from an idea or innovation and movement toward or away from the cost of capital. We can make the fade picture more favorable by focusing on the obstacles to reducing the cost and availability of capital, too.

Frigo: CFOs can play a vital role in improving risk management capabilities of the executive team and board members and help boards to understand both the upside and downside of risk, as described in the article “The CFO and Strategic Risk Management.” In your experience, what’s most critical in getting board members to shift gears in viewing risk as not only a downside but also an obstacle to achieving upside innovation gains?

Koenig: In the first chapter of The Board Member’s Guide to Risk, I discuss the impact that negative framing has on decision making, especially in the realm of loss. Risk is traditionally discussed as the potential for loss. So all the biases that we have as humans around loss impact our analysis of risk-taking, and not favorably. In other words, when boards are considering long-term strategic plans, which necessarily include risk-taking, if we present risk as the potential for loss, these individual board members and boards as a collective of biased individuals will be making suboptimal decisions. That means their companies are more likely to realize fade to the point of value destruction when they frame risk as loss in their discussions.

A progression from contemplating risk as loss ultimately gets to the idea that risk is a cost we allocate when determining the viability of new ideas or innovations. The level of trust that capital providers have in our ability to meet their expectations drives that cost. Perhaps this is where the CFO can play an outsize role, working in coordination with a chief risk officer and business leaders, to allocate the cost of risk-taking as an input like any other expense.

Frigo: Your point of view on risk-taking is important and supported by the research from DePaul University as described in the recent COSO report aptly titled Creating and Protecting Value and research on “Strategic Risk Management at the LEGO Group” (Strategic Finance, February 2012), as well as research on other leading companies. Now let’s discuss your concept of stakeholders as capital providers. In your work, you define stakeholders as capital providers as a way to better understand how to improve risk governance. How would you define the primary stakeholders/capital providers of a company? And why is it important to do so for risk governance?

Koenig: It’s essential for creating the most value that we can integrate stakeholders’ equivalency as capital providers and not some soft, feel-good concept. Too often, we look at a company’s cost of capital as dependent only upon its financial mix of debt and equity and what the market charges the company for those. Financial capital is necessary but not sufficient. Each entity—board of directors, investors, executive leadership, employees and contract workers, retirees, customers, competitors, analysts, creditors, liquidity providers and suppliers, or regulators—has the potential to influence our ability to succeed (our firm risk) because they can provide us with, or take away, some form of capital we need. As such, it’s in our best interest to encourage their willingness to provide us with the form of capital they can provide at the lowest cost possible.

The cost of that capital is a function of what they expect to get from us, for how long they expect to get it, and the risk (in their perception) that they’ll be disappointed—all relative to their other opportunities to put that capital to use. They do this assessment via data and heuristics—feelings. Risk is an emotion that turns out to have substantially more impact on the cost of our capital than any math says that it should. So we want to minimize the risk of disappointment that capital providers perceive. We do this by recognizing the importance of so-called stakeholders as the providers of that capital and try to address their needs.

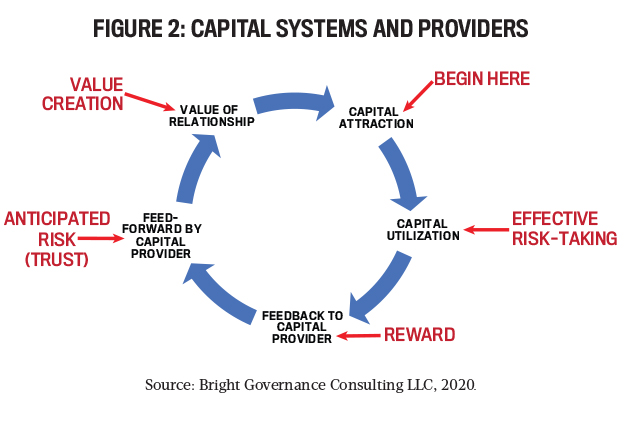

Frigo: In our discussion, you mentioned a capital cycle of a firm that can help in risk governance. How would you describe the capital cycle and its benefits in risk governance?

Koenig: Consider the capital cycle of any organization, from start-up to mega-cap company (see Figure 2). The cycle begins with our need to attract forms of capital. The first evaluation they have of us may be very risky, as there may be no experience with our idea. So, capital at the start is expensive. Ultimately, these capital providers get some feedback from us, and the returns to them either exceed or fall short of their initial expectations. This frames future risk in their minds.

Next, they consider whether to continue to provide us with capital. This assessment is forward-looking, so we refer to this part of the capital cycle as the “feed-forward” mechanism. Feed-forward affects the cost of capital more than feedback. To reduce our cost of capital in all its forms, we need to emphasize the governance of the drivers of these heuristics around risk. Taking this back to Madden’s world, not only does the value of our company increase because our venture portfolio of innovations returns more than the cost of capital, but working to reduce the cost of capital at the same time gives us a competitive advantage. This duality improves the cycle of fade.

Frigo: The DCRO Institute is offering an online course, “The Board Members’ Course on Risk.” How would this inform the work CFOs and their board members do in the area of risk governance?

Koenig: “The Board Members’ Course on Risk” is designed to make board members who aren’t risk experts more prepared for the essential governance of risk-taking. This program supports organizational success and the common problem of biases around loss. It can be taken as online self-study, via study cohorts guided by board members and executives, or with business schools, the first of which is the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. The faculty provide a global perspective and represent financial, nonfinancial, public, and nonprofit entities.

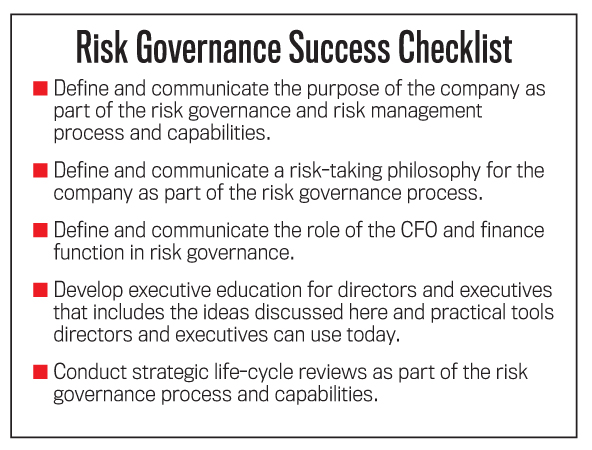

Frigo: The concepts discussed here can help CFOs take a leadership role in improving risk governance to achieve greater long-term value creation through innovation and overcoming the obstacles to achieving corporate purpose. This will require understanding and managing firm risk and developing a risk-taking philosophy driven by innovation and guided by life-cycle thinking.

CFOs can help companies develop and support executive education and discussion sessions with the board and senior management to clarify the role and benefits of risk governance and its relationship to strategy setting and performance measurement, which would support long-term value creation. Risk needs to be managed with consideration for both the upside and downside. The focus within the organizational culture must continually be on eliminating barriers to innovation that can enable companies to achieve long-term sustainable value creation and competitive advantage.

Firm Risk and Life-Cycle Reviews

Firm risk is about the obstacles that management faces that interfere with achieving the organizational purpose. Firm risk increases or decreases in lockstep with changes that degrade or improve the likelihood of achieving the company’s purpose. An increase in firm risk, all else equal, means a greater likelihood for a company to generate lower future financial performance.

In the early stage of an increase in firm risk, management may choose to disregard the warning signs, but nevertheless those inside the company have superior information compared to investors relying on public information. There can be a substantial time lag between a significant change in firm risk and investor perception of this change.

Life-cycle reviews: Management’s success in handling firm risk is ultimately reflected in their organization’s life-cycle track record (Figure 1).

Boards would benefit from evaluating each business unit’s request for capital within the context of its life-cycle track record. Also, there’s an opportunity for a more advanced capability that would further improve the knowledge-building proficiency of boards. Boards could do the same as portfolio managers who use life-cycle data (and the related life-cycle valuation model) when analyzing a company as a potential investment.

Portfolio managers build scenarios, such as optimistic, most likely, and pessimistic, for the firm of interest. These are compared to life-cycle expectations implied in the company’s current stock price. They ask: “What, if anything, do we know that the market does not know?” Importantly, the plausibility of forecast scenarios is judged by comparison to the life-cycle track records of competitors. Finally, analysis is undertaken of any potential competitor, regardless of size, whose current stock price implies exceptionally bullish future life-cycle performance—early feedback of possible big changes ahead that could significantly impact the firm of interest. –Bartley J. Madden

This article is part of the Strategic Finance Creating Long-Term Sustainable Value series, which includes “Creating Greater Long-Term Sustainable Value,” by Mark L. Frigo with Dominic Barton (October 2018); “Strategic Life-Cycle Analysis: The Role of the CFO,” by Mark L. Frigo and Bartley J. Madden (October 2020); and “The CFO and Strategic Risk Management,” by Mark L. Frigo and Richard J. Anderson (January 2021).

July 2021