But have you built good learning skills? Despite the need for continuous learning, these skills typically aren’t a point of emphasis. Many of us tend to fall back on whatever learning habits we stumbled into during primary and secondary school. Meanwhile, the amount of information and skills we need to keep up with continues to grow. Fortunately, there are a number of simple research-based habits that can spruce up our abilities to learn better in less time.

LEARN TO LEARN

Research literature on the psychology of learning uses the term “metacognition,” which informally means “thinking about thinking.” Most of us grew up with the idea that some fortunate people are born smart, and others less so. In contrast to this widely held view, however, research strongly indicates that we can grow our intelligence. As Janet Nay Zadina points out in her book Multiple Pathways to the Student Brain, the brain is like plastic and can rewire itself with learning experiences. The bottom line is simple: We can become smarter.

Improving your intelligence is a liberating idea because it can help you embrace a growth mind-set toward learning rather than limit yourself because you think you aren’t smart or talented enough to learn something well. And the good news is that learning is a skill, informed by metacognition research. So not only can you increase your intelligence, but you can do so better with improved metacognitive (i.e., learning) habits.

MONITOR YOUR LEARNING LEVELS

Depending on your particular needs, different skills and knowledge areas will require different levels of thinking and expertise. One common framework is Bloom’s taxonomy (see Figure 1). Before you start continuing education or other learning endeavors, ask yourself: “At what level of Bloom’s taxonomy would I like to (or need to) learn this material?”

The level of learning is a choice. For some continuing education topics, the lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy (remembering and understanding) may fit your needs. At Arizona State University, for example, we have numerous software packages. For my needs and responsibilities, merely remembering and understanding the travel receipt software is sufficient since I don’t need to use it often. But I do regularly use Stata and SAS software for research purposes, so mastering those at a higher level of Bloom’s taxonomy is important.

BE AN ACTIVE LEARNER

After you’ve determined the learning level needed, how can you best achieve it? Metacognition research offers several answers. The specific techniques vary and apply to different contexts, but a common theme is the need to be proactive while learning. Many of the old methods we’ve used have led us to be passive learners, writing down what we hear or taking in what we read without much thinking. But our goal is to do more with the information, not to be a stenographer who merely creates a transcript of a study session. Let’s take a look at some techniques that can help.

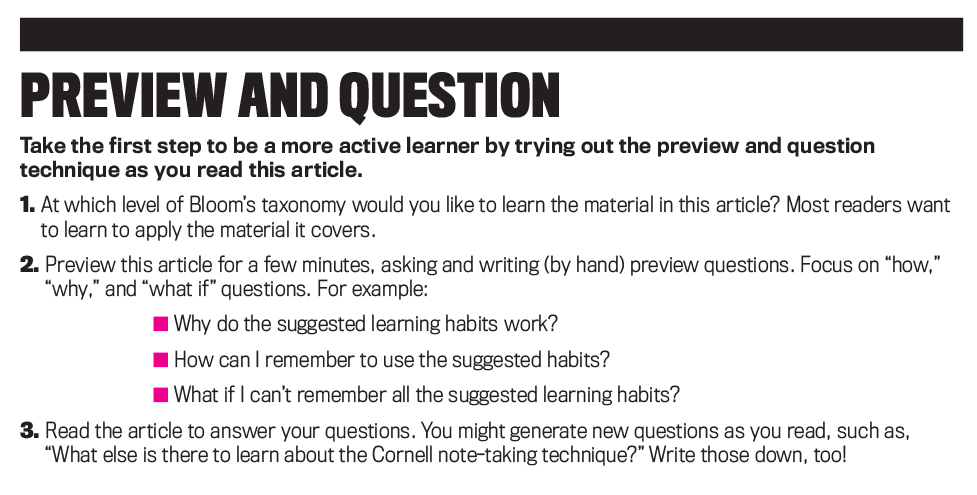

Preview course material by asking yourself questions. As you begin, look through the material you’re about to study and ask questions. Focus on “how,” “why,” and “what if” questions because they help you engage your mind at higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. And don’t just ask them in your head—write them down.

When you preview material by asking questions, you’ll naturally find yourself seeking answers as you engage with the learning material. Previewing helps regardless of the type of learning material, such as live or recorded lectures, online courses or videos, readings, and so forth. See “Preview and Question” to try applying the technique to this article.

Interleave intense study sessions. Instead of dedicating hours and hours to one topic, interleave your intense learning sessions. “Interleaving” means you should study one of your learning topics intensely for 30 to 50 minutes, take a break, then study a different topic. Research indicates that humans learn better with this length of study session.

In these intense sessions, focus only on the material you’re learning. Minimize distractions both in your mind and in your physical environment. This is vital to learning well and in less time. Multitasking damages productivity. Although we often feel more productive, studies indicate that we take (on average) 30% longer to complete tasks when multitasking—and with twice as many errors. In addition, research indicates that it takes 10 to 15 minutes to get our train of thought back to a task after answering emails or instant messages.

Interleaving intense study sessions improves learning because you tend to be able to apply, judge, and evaluate your new knowledge better. In other words, the study sessions will help you move to the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy in less time. I particularly see improved scores on exams when my accounting students start interleaving their studies.

Take notes by hand. Whether writing your preview questions or taking notes while reading a text or watching a video, write everything out by hand. Writing by hand helps you learn because it requires you to think, construct, and assimilate. In contrast, metacognition research has found that taking notes by typing on a computer keyboard encourages passive dictation and less learning (see bit.ly/3ob0PWg for more).

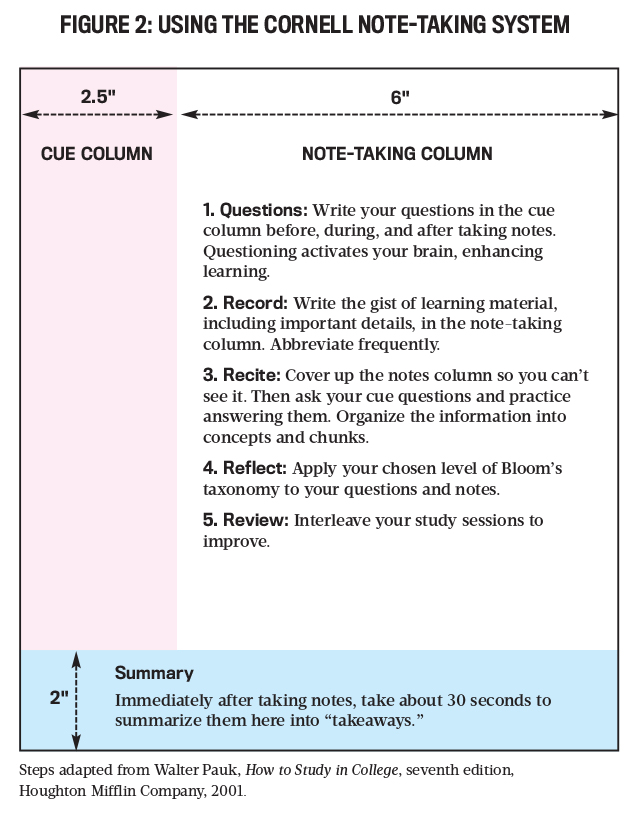

Take better notes. Active note-taking is important for learning, particularly when numerous continuing education courses tend to deliver passive bullet-point lists of ideas and concepts. One method to try is the Cornell University note-taking system. (See Figure 2 for a slightly modified approach, and visit bit.ly/3pEA91P to learn more about the original system.) Using that process, also add in the following:

- Start your note-taking with your preview questions for the material presented and reference them in your notes when they’re addressed.

- After completing a lecture, presentation, or reading session, actively finish your notes by completing answers to your preview questions and perhaps writing out new questions to be answered later.

- Associate concepts and ideas in your new notes to your previous knowledge.

- Write down any follow-up activities you choose to pursue. For example, I use the Summary section to list follow-up activities.

Read and listen cumulatively. How often does your mind wander or drift off while reading or listening to a presentation? You know that feeling when you read a paragraph in an article or listen to a speaker only to “wake up” not knowing what you’ve read or heard. The idea of reading or listening cumulatively is simple: Read (or listen to) a sentence, stop, and consciously think about how it relates to the prior sentence.

Depending on the difficulty of the material and your level of engagement at that time, you might want to try reading paragraphs or sections of an article or textbook before you try relating them to prior material. Most of my students initially assume cumulatively reading will consume all their time (as I did, too). After they try it, however, they all note that it saves them time because they remember new information better, assimilate it better, and can more quickly use it to solve problems. In other words, they’re learning at higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. And it saves them from rereading material.

Minimize highlighting. Don’t highlight reading material (which most of us habitually do). This is a passive learning habit. Instead, write a question. If you see a bolded term, for example, don’t just highlight it as an important term. Write down a question such as “What is the definition of [bolded term]?” or “How does [bolded term] relate to other concepts in the article or textbook chapter?” By asking questions, the number of highlights should taper off while your learning improves.

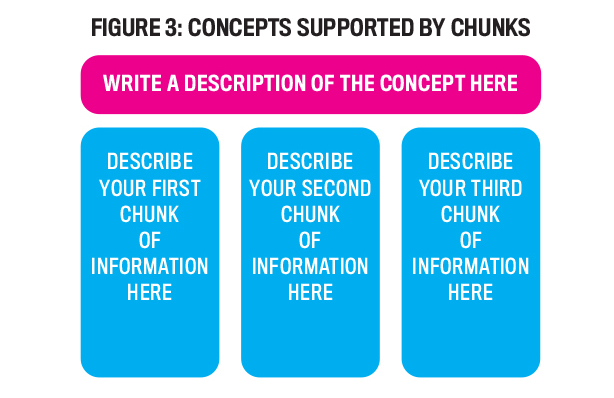

Actively organize your new knowledge into concepts supported by chunks. During your intense study sessions, actively organize new material into concepts and chunks (see Figure 3). Describe a concept across the top horizontal rectangle. Then organize material that supports the concept into chunks of information that you can remember. Place each chunk of information in a vertical rectangle below the concept. You might want to connect chunks, order them, or capture relationships among them. You might try it with this article.

This organizational tool helps you recall information as you actively organize it. And the mapping process will help you identify gaps in your knowledge that you can address to improve your learning.

As you learn more about the concepts, actively reorganize your knowledge into broader, more encompassing concepts and bigger chunks. Experts have large concepts and chunks in their areas of expertise, while new learners tend toward many smaller concepts supported by many smaller chunks of knowledge. An example for me is ratio analysis. This is something I’ve learned about and practiced for years. So when organizing my knowledge, “ratio analysis” is a single concept supported by a few large chunks of knowledge. For my students learning about it for the first time, however, “ratio analysis” entails many small concepts and chunks. They learn better as they actively assimilate “ratio analysis” into a few concepts supported by bigger chunks of information.

A key question you will ask yourself is, “Do I have the best concepts and chunks?” Compare with fellow learners. Make a point of asking experts how they chunk concepts. Notably, it’s primarily my better-performing students who ask me how I organize the complex accounting topics they’re learning.

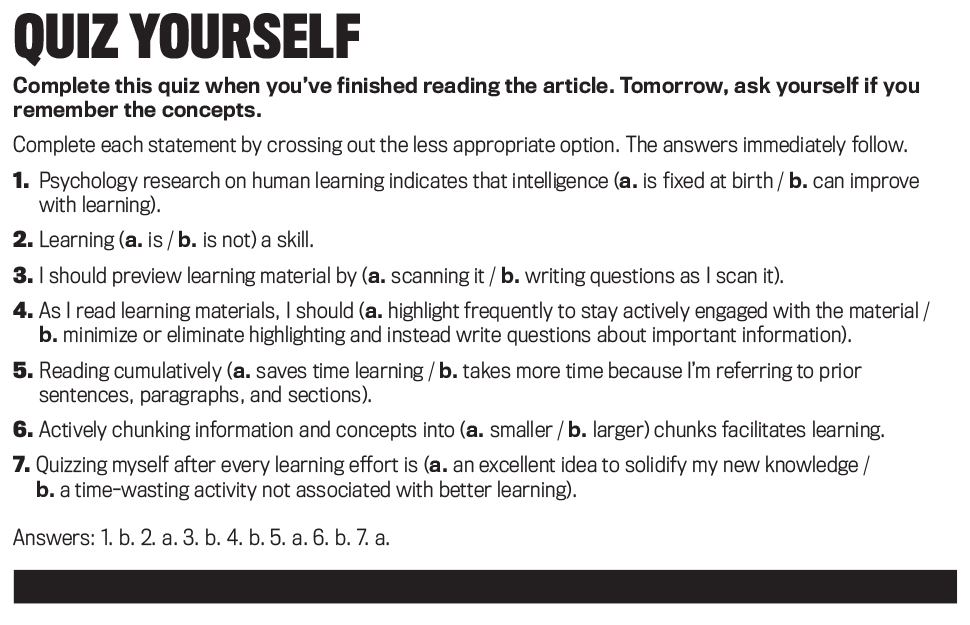

Quiz yourself. When reviewing material that you’ve studied, whether it’s textbook material or even your notes, don’t just reread it. This will only help remembering and understanding, which are the lower levels in Bloom’s taxonomy. Quizzing, however, helps you assimilate your knowledge into concepts and chunks. It also helps you retrieve knowledge and identify gaps or misunderstandings in your knowledge.

Of course, you need questions to quiz yourself. Use your questions from previewing material and study them intensely. Also, seek out questions from other sources, like different course materials from other instructors.

Use the 30-second exit technique. At the end of a continuing education learning session or an intense study session, take 30 seconds to write out the key concepts and ideas you just learned. This technique takes very little time, but it helps you remember your new knowledge, identify questions you’ll want to answer, and plan your next intense, interleaved study sessions.

Use exam wrappers. Most of my students glance at their exam scores and are either happy, indifferent, or disappointed at the result—and then they simply move on. With exam wrappers, you ask yourself questions about your performance in order to improve your learning skills. For example, did you plan an appropriate amount of time given the exam’s complexity, coverage, and your learning objectives? Did you employ learning best practices? Were you sketchy on needed prior knowledge? Use your answers to write a note to yourself (i.e., the exam wrapper) describing how you intend to study for future educational endeavors.

LIFELONG LEARNING

The need to learn new skills or information never goes away. Whether you’re trying to pick up new skills or further develop your expertise for your job, studying to earn a professional certification like the CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) to advance your career, or still in school working toward a degree, effective metacognitive (i.e., learning) habits will help you get the most from your time and effort with the added benefit that you can grow your intelligence.

January 2021