We’ve learned more about virtual meeting platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams than we ever thought possible. And we’ve figured out how to work within and around corporate policies and procedures that were designed for an in-person world. But flexing our creative muscles shouldn’t be reserved for times of crisis; creativity is needed every day, crisis or not.

Business leaders recognize the need for creativity in achieving success. An IBM survey found that executives believe that creativity will be the most important characteristic for successfully navigating the business world of the future, and a 2017 McKinsey study of its Award Creativity Score revealed that the most creative companies outperform peers in terms of financial performance and innovation.

Adobe’s State of Create: 2016 report found that respondents believe corporate investments in creativity increase employee productivity (78%) and happiness (76%), foster innovation (83%), and improve financial performance (73%). Yet while 64% of global respondents felt that creativity was critical to the economy, only 31% believed they were achieving their creative potential. (In the United States, it was 77% of respondents recognizing creativity’s importance and 44% believing they’re achieving that potential.)

CREATIVITY CHARACTERISTICS

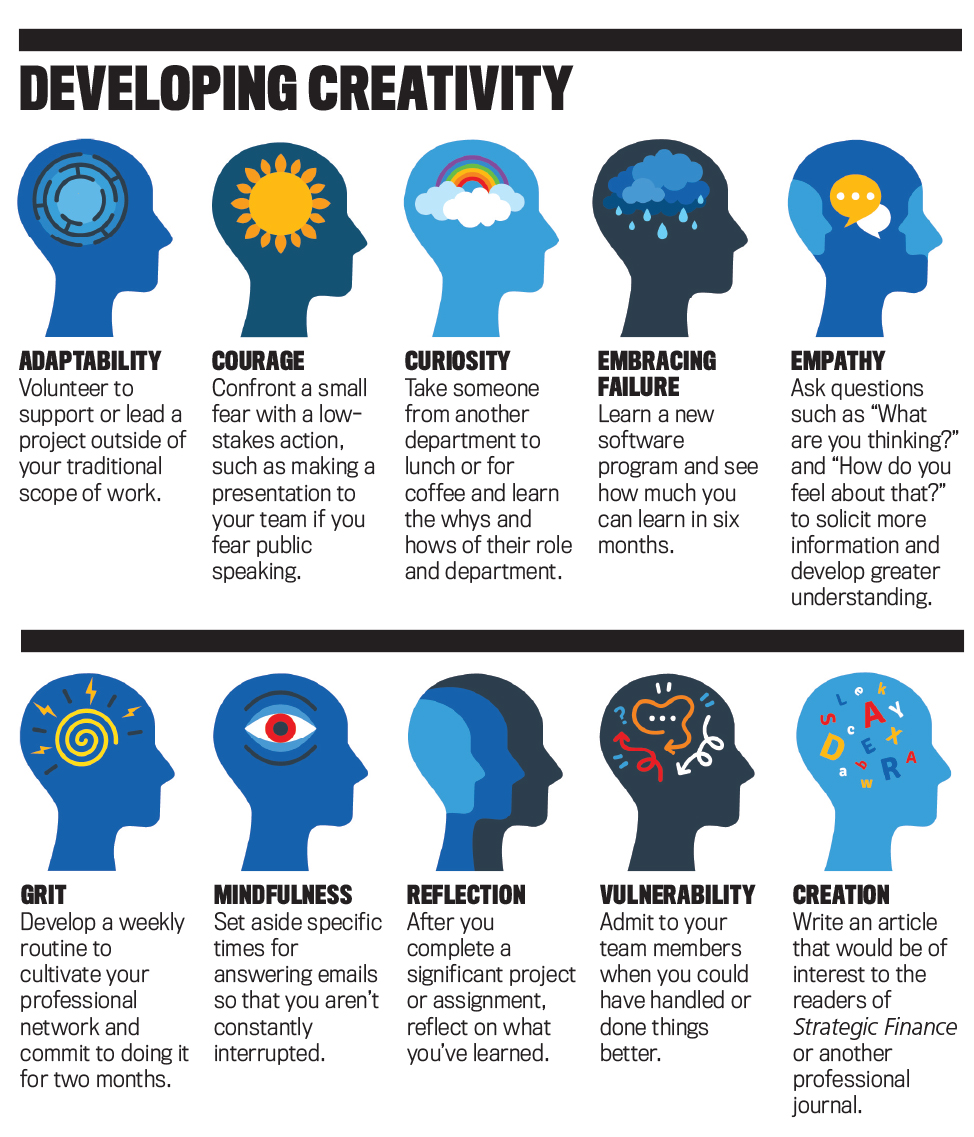

What does creativity look like for accounting and finance professionals? How can we identify a creative employee? And how can an organization nurture that creativity once it’s found? The following 10 characteristics of creativity provide a starting point. If you find employees with these characteristics and develop a corporate culture that emphasizes and values these traits, you’ll be well on your way to nurturing a creative culture that inspires innovation and business growth. (See “Developing Creativity” for an overview of ideas.)

Adaptability

Just as Darwin argued that the survival of a species depends on its ability to adapt to its environment, organizations today must adapt to their environment to survive and thrive. Boston Consulting Group’s Martin Reeves and Mike Diemler applied this to business in a 2011 Harvard Business Review article: “Instead of being really good at doing some particular thing, companies must be really good at learning how to do new things.”

During the recent pandemic, we’ve seen organizations adapt, as apparel companies such as American Giant, Prada, and Citizens of Humanity switched from making clothes to making face masks; retailers ranging from Gap and Old Navy to Tractor Supply Co. started to offer delivery and contactless curbside pickup services; educational institutions from pre-K to Ph.D. quickly adapted to remote online education; and professional organizations, such as Emmy sponsor Television Academy, moved large meetings and conferences to virtual offerings.

Accounting and finance professionals have also had to adapt, as monthly, quarterly, and year-end close routines have been completed with staff members working remotely and with auditors conducting their field tests off-site.

How can you improve your adaptability? The next time your company is evaluating a new program, system, or training, be the first to volunteer to pilot this change. There are countless ways like this to volunteer to support or lead a project outside of your traditional scope of work.

You don’t need to go big, though. Start with a small step in your personal life to build up your adaptability thinking. From these settings, you can move to higher-stakes professional settings with an improved adaptability mind-set.

Courage

Bold moves made in the name of adaptability will challenge the status quo, and such decisions may not be popular with some in the organization. While there are risks involved worth measuring, courage is a sure path to innovation. Rank-and-file employees must have the courage to suggest and make bold moves, regardless of the outcome, but leaders must also have the courage to trust employees to do the right thing and then have those employees’ backs as the new ideas are implemented across the organization.

As operations moved out of the confines of the physical office during COVID-19, financial services leaders showed courage in dealing with sensitive issues such as maintaining data security while operating in a remote environment. Physicians and mental health professionals moved from office visits to telehealth appointments. In all these cases, decisions that most executives previously weren’t willing to champion suddenly became necessary moves.

3M demonstrates courage through its 15% Culture approach, which has “encouraged employees to set aside a portion of their work time to proactively cultivate and pursue innovative ideas that excite them.” Without this courage, Post-it Notes may have never seen the light of day.

Again, you can build your courage by starting small. For example, if making presentations is what you fear, volunteer to be the presenter the next time your team is being asked to provide a presentation to your supervisor. Ask your team and supervisor for feedback on your delivery and effectiveness. This is a low-risk opportunity given that it’s with your immediate team with whom you most likely have a good rapport and confidence.

As you improve your presentation skills, seek opportunities to present to larger audiences such as your entire division. Prepare by rehearsing your presentation, anticipating questions, planning your responses, and making a checklist of critical points you want to communicate. Over time your courage will grow while your fear of presenting shrinks.

Curiosity

Harvard professor Francesca Gino studies curiosity in business organizations and has found that most breakthrough discoveries and remarkable inventions are the result of curiosity. The finance manager may ask, “Why do we see a dip in revenue in the winter months?” “Why do expenses continue to rise year after year?” “What if we did this?” “How can we make our reporting process more efficient?” These are the types of questions that lead to incremental improvement and possibly disruptive or revolutionary change. Indeed, researchers at INSEAD, measuring curiosity on a seven-point scale, found that for each point increase in curiosity, creativity increased by 34%.

As accountants, we often need to use our professional skepticism, so don’t be afraid to ask “Why?” or “How?” And if you can’t get an answer right away, do the research to develop an answer. Grow your understanding of the entire organization by connecting with employees from other departments across the organization. Take someone from marketing or sales to lunch or for coffee and learn the whys and hows of their role and department. Outside of work, embark on an adventure of lifelong learning by taking a class in a new area of interest and read books representing different time periods and genres. Feed your curiosity, and it will grow.

Embracing failure

Everyone fails at some point in life. If you aren’t failing regularly, you probably aren’t stretching yourself far enough to reach your full potential. Failure must be viewed as an integral part of the learning and creating process. It should be embraced and celebrated. But it’s the step we take after the failure—reflection—that brings out our creativity. Through reflection, we work to discover why we failed and what we need to do differently. In this way, the failure and reflection become the stepping-stone to making progress during the next iteration of the idea.

Thomas Edison is one creative who embraced this notion when he claimed, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” Imagine where we would be today if he’d stopped and given up after any of these failed attempts. So, remember Edison the next time you have trouble getting a spreadsheet formula to work or a document formatted properly.

Start anywhere. Pick a new skill you’d like to develop and focus on it for a period of time while giving yourself permission to fail. Examine the results, identify how you can improve, and try again. You could learn a new software program or seek a new organizational role and see how far you’ve come in six months. You’ll learn that you’ll have many failures early on but will get better over time and build your appetite for embracing failure.

Empathy

Empathy is the first stage of human-centered design thinking. It’s only in understanding that perspective that we can begin to create an effective solution. Otherwise, we might create a solution to a completely different problem than the one we set out to implement.

Empathy is critical for accounting and finance professionals who are providing information to decision makers. Without understanding the nature of the information request and its intended use, it will be difficult to provide the best information to support the decision process. It also means that you need to know more than just the accounting and finance portion of the organization so that you can understand various organizational perspectives. Empathy is also a critical tool for managers as they work to develop their accounting and finance staff members’ careers.

Improving your ability to practice empathy requires a deeper understanding of others, which requires you to listen intentionally. The next time you’re meeting with a colleague, focus on listening, maintaining eye contact, and providing nonverbal cues such as nodding to show your engagement. Wait to provide advice and comment until after they have fully explained their situation and you understand the problem. Ask questions such as “What are you thinking?” and “How do you feel about that?” to solicit more information and the opportunity for greater understanding, and don’t be afraid of moments of silence.

Identify your implicit biases by completing an online quiz, such as those available at Harvard’s Project Implicit website (bit.ly/3qxwWQx), and then be aware of these as you converse with others. Educate yourself about other cultures by reading books, attending cultural events, and engaging in meaningful conversations.

Grit

Angela Duckworth, who centered the term in her 2016 book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, defines grit as a “combination of passion and perseverance for a singularly important goal.” We can also think of grit as tenacity, persistence, resilience, and toughness. Author J.K. Rowling demonstrated grit when she kept returning to writing her first Harry Potter book after several life events took her away from writing. And then once she began submitting the manuscript to publishers, she showed even more grit through 12 publisher rejections. Today that grit has made Rowling a billionaire; she’s built a franchise that in 2018 was estimated to have generated $25 billion in revenue.

Likewise, every candidate who has sat for professional certifications such as the CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) and the CPA (Certified Public Accountant) and had to retake an exam section has demonstrated this grit.

But grit is like a muscle. It must be developed and strengthened with time and intentionality. When you find yourself on a project or task that isn’t progressing because you have lost motivation and interest, seek help from a colleague or performance manager. Recruit others or delegate a task to get the added push you need to complete a pending project. Develop a plan or checklist for completing the project’s final tasks to help focus your effort and create a shorter, more attainable timeline.

In other words, grit gets stronger from practice. Select a habit you would like to develop, say, a daily 30-minute workout session, weekly routine to cultivate your professional network, a blogging schedule, or time blocked to read The Wall Street Journal daily, and commit to doing it for a month to build consistency in accomplishment. If you miss a day or two, accept it and move on until you have a full month without missing a day. Over time you’ll find that displaying grit can be a commitment to a process.

Mindfulness

It may be tempting to think that creativity is the result of random sparks of genius, but that isn’t the case. Creativity requires mindfulness—an awareness and focus on the task at hand. Being mindful means clearing your brain of noise and distraction so that you can focus completely on what you’re doing at the moment. In this way, you’ll gain greater clarity of thought and remove biases and filters that could impede creative thinking. Bosch, Google, SAP, and Aetna are some of the many companies to have recently implemented mindfulness programs. After more than 13,000 employees completed Aetna’s mindfulness training, the company saw a 28% reduction in employee stress levels and $3,000 in productivity improvements per employee.

Block out some time on your calendar each day for creativity and mindfulness. Turn off your cell phone and email notifications during this time to remove distractions. At work, set aside specific times for answering emails so that you aren’t constantly interrupted. Turn off your cell phone notifications as you go into a meeting and then place it facedown on the table or leave it in your pocket. Focus on the meeting and connecting with your coworkers in the room.

If you’re working to meet a reporting or filing deadline, remember to take periodic breaks and walk around the office or around the block to get some fresh air. Take time for lunch away from your desk. Using this time to clear your mind will lead to improved concentration and effort when you return to the task at hand.

Reflection

Throughout a creative process, there must be time for reflecting on what has happened in the past, what is happening in the present, and what might happen in the future. It’s an activity that needs to be completed after both success and failure to identify effective practices and those that could be improved to ensure future actions are as effective as possible.

We can identify personal strengths to capitalize on, weaknesses that require improvement or reliance on others, and mistakes that must not be repeated in the future. And as we purposefully reflect, we will likely end up asking more questions that can guide future endeavors.

While reflection is typically a component of annual performance reviews, don’t wait until then to reflect on your progress. After you complete a significant project or assignment, reflect on what you’ve learned. If this was a team project, talk with the other team members and reflect as a group to determine what went well and what could have gone better. Schedule a lunch or coffee break with your supervisor to check in on your progress and development.

Each month, review what you have accomplished and decide if there are particular characteristics you want to focus on in the coming weeks. Consider keeping a “creativity journal.” Spend a few minutes at the end of the day reflecting on which of the 10 characteristics you worked on and how you developed your creativity.

Vulnerability

Most of us don’t like being vulnerable. But if we have the courage to show up and be vulnerable, to really open up to others, positive results can occur. Brené Brown, a professor at the University of Houston who has spent years studying vulnerability, believes there is “no creativity without vulnerability.” Creating something new requires us to take risks and be open to uncertainty and failure, and that’s part of being vulnerable.

Instead of asking a colleague “How’s your day going?” start a conversation by admitting that something isn’t going well for you and asking for their advice. Admit to your team members when you could have handled or done things better. Volunteer for a temporary assignment in another department that will stretch your technical accounting and finance knowledge and skill set. Or go a step further and volunteer for such an assignment in an international location.

Creation

Have you ever assembled anything from a box of parts and a set of instructions? Do you remember the pride you felt when you finished and could see the results of your labor? Having some “skin in the game” brings buy-in to the process and a greater sense of accomplishment. Researchers Michael I. Norton, Daniel Mochon, and Dan Ariely call this the “IKEA effect.” They find that we place more value on something we have physically made than on something made by others. So, creativity can’t be just a thought exercise. It requires the actual creation of something.

Early-stage companies and new divisions within an organization are prime opportunities for creation since these situations don’t provide prior-year working papers, templates, or processes to follow; therefore, it forces accounting and finance professionals to roll up their sleeves and create something from scratch.

START WHERE YOU ARE

Your creative innovations begin with you. Make something; it doesn’t matter what. Pick a new recipe and bake something. Pick up some paint and a canvas and then paint a picture. Plant something and watch the plant grow under your care. Or put your professional knowledge to creative use and write an article that would be of interest to the readers of Strategic Finance or another professional journal.

Most people see accountants as rule followers, not as creative innovators, and the term “creative accounting” is typically used in reference to questionable accounting practices. But accountants need to be creative to help their organizations thrive. Every new accounting standard requires creative thinking to interpret the standard and develop the policies and procedures required for its implementation.

Using data analytics to find answers to important questions requires accounting and finance professionals to be creative when looking for and explaining relationships hidden in the data. And as we’ve all learned during the pandemic, creative solutions to old and new problems are crucial for ongoing success. So, the next time someone calls you a creative accountant, thank them for the compliment!

Additional Creativity Resources

Peter Bregman, “Empathy Starts with Curiosity,” Harvard Business Review, April 27, 2020.

Brian T. Edmondson, “5 Business and Life Lessons on Grit and Determination I Learned from the Late, Legendary Gloria Vanderbilt,” Entrepreneur, July 3, 2019.

David Gelles, “How to Be More Mindful at Work,” The New York Times, November 1, 2018.

Matt Richtel, “How to Be Creative,” The New York Times, January 31, 2019.

Martin Zwilling, “How to Embrace Failure and Use It to Succeed,” Inc., April 4, 2019.

April 2021