The criticism suggests information is being delivered to executives, managers, and employee teams who need valid information for insights and better decision making. Yet, the time has come when these two parties need to reach some degree of consensus and mutual inclusion. Businesses can’t continue to support multiple and rival viewpoints. Clear-eyed thinking and technology can now be used to support such a mutual coexistence.

According to John Exline, CFO of Clark Investment Group, “Many managers’ eyes glaze over when they are given standard costing information. Accounting is outside their comfort zone. Exposing managers to ABC, which displays logical relationships and visibility to the causes of costs, is useful for educating them about management accounting and cost controls. It prepares them for an eventual day that their company will implement ABC.”

We recognize that standard costing must comply with regulatory and statutory rules for external financial reporting for government regulators and the investor community, but the calculations for standard costing, specifically for overhead allocations, can apply ABC principles, thus providing more accurate costing while still being in compliance with external financial accounting.

What should be appealing to ABC advocates is that this significant step with standard costing creates a bridge to extend the application of ABC to support management accounting with possibly more granular ABC (e.g., more activity costs with their associated drivers). An even greater appeal is to apply ABC to assign and trace expenses reported below standard costing’s gross product profit margin (e.g., distribution channel, selling, marketing, and customer service expenses) to report a profit and loss statement for each customer in the domain of management accounting. This step then links customers, who are a company’s source of financial creation, to its shareholders and owners. It completes the bridge.

A PRIMER ON MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

Standard costing was born out of the need to properly manage and value inventory of products inclusive of the major costs of production of direct labor, direct material, and indirect expenses (commonly referred to as overhead). The basic method involved determining and applying a cost per labor hour or cost per machine hour “burden rate” for each of these expense amounts for each product produced during the fiscal year. Under this method, the indirect overhead expenses would therefore be calculated with the same proportion as the direct expenses.

For a while, this method worked because (1) the purpose was to value inventory and cost of goods sold (COGS) for external financial regulatory compliance reporting, and this approach was sufficient for doing so, and (2) indirect overhead expenses were a relatively small proportion of the total calculated cost, so their cost inaccuracies wouldn’t materially affect the total costs.

But by the 1980s, many were starting to cry foul. Over time, these volume-based cost allocation amounts for overhead (without any cause-and-effect cost consumption relationships) were being used for purposes other than inventory valuation, including analysis of profit margins by product and service line and even for distribution channels and customers—a profit and loss report for each customer.

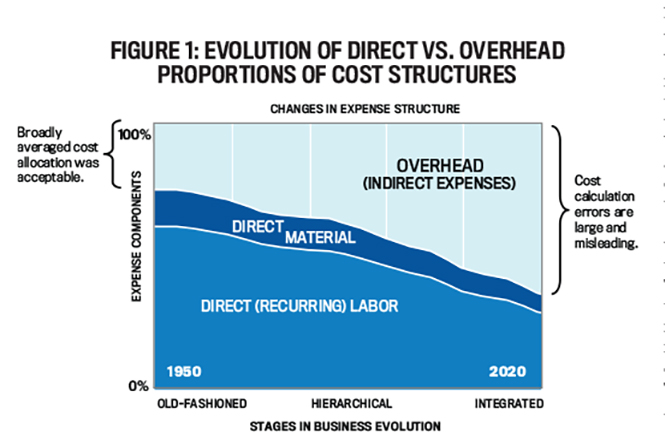

With a proliferation of more types of products (e.g., more colors, sizes, and ranges) and their associated increase in diversity and variation, this caused complexity, which in turn required more indirect expenses to manage that complexity. As a result, the overhead was becoming a larger proportion of the total cost, thus introducing more error in the calculation. The result was that standard costing was losing its relevance to support decision making. (See Figure 1.)

In 1987, H. Thomas Johnson and Robert S. Kaplan first published their seminal work, Relevance Lost: The Rise and Fall of Management Accounting, that started, or at least facilitated, an uprising. In the 1990s, ABC became a popular method to calculate and look at these costs differently. Under ABC, the indirect overhead expenses from resources are grouped into “cost pools” of similar work activities of workers and assets. These resources’ expenses are traced and assigned to their work activities based on relevant drivers with causal consumption relationships, which are then subsequently traced and assigned to final cost objects (e.g., products, service lines, channels, and customers) based on other causal and relevant drivers.

This is in contrast to standard costing’s allocations, whose proportionality of indirect expenses to direct expenses makes them more like spreading butter across bread, thereby violating costing’s “causality principle.” ABC advocates prefer to not use the term “allocate” because savvy managers, who recognize the deficiency of those broad-brush cost allocations, roll their eyes when they hear the term “cost allocation.” They know the calculations are flawed and misleading.

The result was that when the indirect overhead expenses, which had been expanding to substantially higher proportions of the total cost, were expressed this alternate way, very different and more meaningful results were obtained. Tim Ketterman, global finance director of OPW Fueling Components, said, “I am often asked how some of our product offering can cost so much. This generally goes into an explanation of standard costing and how indirect overheads are allocated to products. As more and more nonfinancial data points are now being tracked throughout operations, the integration of these for assigning cost to particular products becomes available for use and therefore can bring more understanding of what is driving our product cost.”

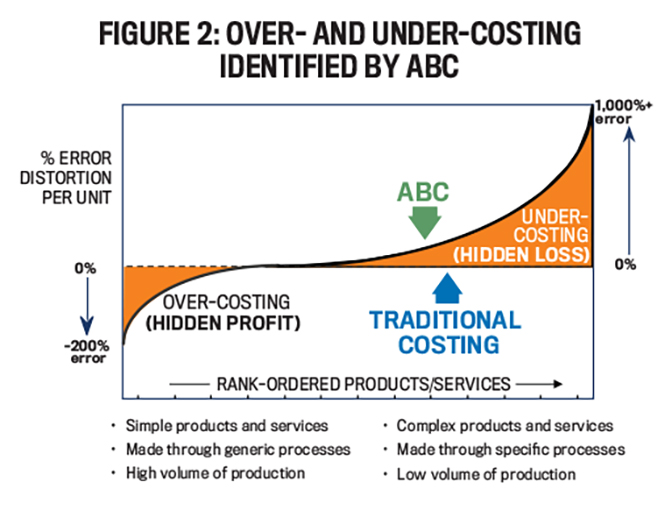

At its root, ABC was able to detect and reveal the cost of diversity, variation, and complexity of products and service lines. ABC exposed, for example, that high-volume simple-to-make products were subsidizing certain low-volume, high-complexity products, indicating the latter to be less profitable or even unprofitable. This contradicted the prevailing beliefs that had been reinforced by the standard costing system, which made them seem more profitable due to their high gross profit margins and low volume-based overhead. A popular phrase by ABC advocates is, “It is better to be approximately correct than precisely inaccurate.” This cost subsidization is illustrated in Figure 2.

But the new ABC information was viewed by many to come with a substantial effort and a high price to acquire it. The perceived administrative effort spent to collect all of the needed source data, model it, validate it, calculate it, and report it was deemed too high by most organizations and not worth the effort. That said, the process for calculating ABC costs has improved dramatically with (1) newer information technologies that can automate a great deal of it and (2) rapid prototyping with iterative remodeling ABC implementation methods to quickly right-size the model in weeks and not months. Yet old beliefs and perceptions die hard.

Many organizations will continue to undertake standard costing as part of their overall external financial income statement and balance sheet reporting process to satisfy government regulatory agencies and the investment community. Standard costing is embedded and inherent in commercial enterprise resource planning (ERP) software vendor systems such that a large deviation from standard costing is deemed not feasible, even if it’s desired.

Eventually, all inventory and COGS amounts need to be reflected in terms of external financial reporting’s Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) methods such as last-in, first-out (LIFO) or first-in, first-out (FIFO); and standard costing is sufficient as the means toward achieving that reporting. When expenses and their calculated product costs are aggregated as much as they are for external financial statements, restricted to and summarized with line of business reporting, then indirect overhead cost allocation methods become less consequential.

But all processes can benefit from improvement. As such, one should consider a way to obtain the benefits of ABC and introduce its accounting method either in parallel to or even into a standard costing setting, so that both costing methods can coexist without scrapping the whole underlying operational process.

Stathis Gould, director of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), said, “As trusted business partners, management accountants provide information and insights that enable a business to make critical decisions such as on pricing, productivity, supply chain, and investment. To be perceived as contributing to an organization’s efforts to create value to customers and other stakeholders, enhanced managerial costing and modeling are a prerequisite. Advances in technology also now offer a significant opportunity to efficiently deliver principles of ABC and resource consumption accounting to enable real-time analysis and reporting.” So where does ABC fit in standard costing? The answer lies in the derivation of the indirect expense overhead rates.

THE STANDARD RATES DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

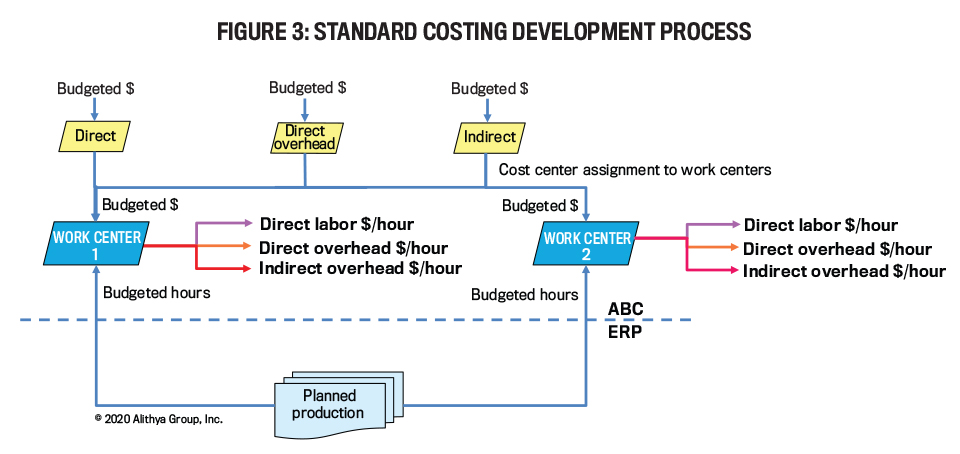

Figure 3 depicts the process for determining expense overhead rates in standard costing. It’s typically an annual exercise that’s part of the overall budgeting process. The starting point is below the dotted line where sales plans, based on the company’s objectives and expectations, determine the volume and mix of products that are expected to be produced and sold in the forthcoming budget or forecast period. From these projections, production planners can identify what raw materials will be needed, what components will need to be procured or produced, and how much direct labor and equipment use is going to be required.

These direct labor and equipment requirements can be derived because every product has what’s commonly referred to as a “bill of materials” and a “labor routing,” like a cooking recipe in which the former is the list of ingredients and the latter are the preparation instructions. Every product has a hierarchical arrangement of required materials and labor. Commercial ERP systems typically capture the labor requirements and equipment needs as direct labor hours and machine hours and do so at a “work center” level of detail.

After production planning derives the direct labor and machine hours, financial analysts work on the part of the diagram above the dotted line. They determine at a cost center or department level what the anticipated expenses are that will be needed to support the intended production—both the direct and the indirect expenses. They do so based on standards and past experience or on methods such as zero-based budgeting. They budget everything for the plant(s) including the direct cost centers that house the wages of the direct labor resources; the direct overhead cost centers that house the benefits and all other expenses of the direct labor resources; the indirect cost centers; and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) department expenses.

Indirect expenses are those related to the sustainment of the manufacturing process but that aren’t directly consumed or incurred with each unit of production. Examples of these costs include material handling, equipment setup, equipment maintenance, product inspection, quality assurance, utilities, insurance, and a portion of plant management. All other expenses, such as corporate, legal, and nonproduction finance, to name a few, are considered SG&A and aren’t included in the standard cost of a product.

After budgeting the anticipated expenses by category (direct, direct overhead, and indirect overhead) and by cost center, projected cost allocations are made to work centers based on—or what should ideally be based on—relevant drivers. Typically, direct and direct overhead expenses are either dedicated 100% to a single work center or are allocated based on projected labor hours or machine hours. Indirect cost centers are allocated as well, based on machine hours for areas such as utilities and maintenance, or other metrics such as square footage, head count, or other obtainable metrics.

The amounts that are allocated into work centers under the three categories of direct, direct overhead, and indirect overhead are then merged with their projected labor and machine hours and, through the magic of division, the resultant cost per hour rates are determined.

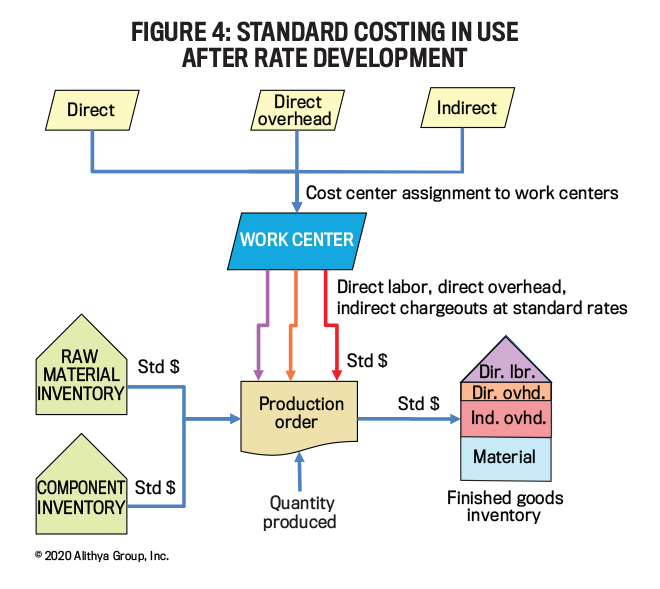

These rates are then used as shown in Figure 4 on an ongoing basis during the year for the company’s actual cost of production, COGS, and inventory valuation. As indicated earlier, GAAP requires inventory and COGS to be reported under bases such as LIFO, FIFO, or a weighted-average value. Standard cost isn’t one of the choices. Therefore, at the end of the year, companies go through an exercise to adjust inventory and COGS to one of these methods. As long as inventory levels are stable year to year, this adjustment can be kept to manageable levels.

EXTERNAL FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING VS. INTERNAL MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

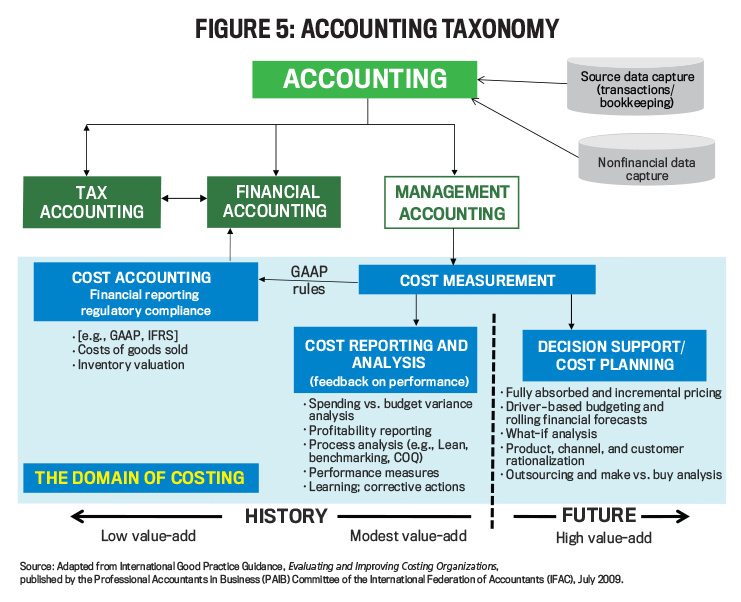

Figure 5 illustrates the large domain of accounting as a taxonomy similar to the field of biology with plant and animal kingdoms. The three accounting “kingdoms” include (1) tax accounting, (2) financial accounting, and (3) management accounting. In the figure, the two types of data sources are displayed on the upper right. The upper source is from financial transactions and bookkeeping, such as purchases and payroll. The lower source involves nonfinancial measures such as payroll hours worked, number of products made, or services delivered. Many of the latter are the activity drivers used with ABC. These same metrics can also be forecasted to create driver-based annual budgets or rolling financial forecasts.

Each type of accounting serves different purposes:

The external financial accounting component is intended for external statutory reporting for government regulatory agencies, banks, stockholders, and the investment community. Financial accounting follows compliance rules aimed at economic valuation, such as for a financial balance sheet’s inventories and income statement’s COGS. This information isn’t sufficient for decision making. This is where standard costing is applied.

The tax accounting component is its own world of legislated rules.

The management accounting component is segmented into two categories: (1) cost reporting and analysis, and (2) decision support with cost planning. The purpose for both is to gain insights and make better decisions, including planning and resource allocation (e.g., budgeting).

To oversimplify a distinction between financial and management accounting, external financial accounting is about valuation while internal management accounting is about creating financial value through good decision making.

The message of the value-add spectrum is that the value and utility of the accounting information increase, arguably at an exponential rate, from the left side to the right side of the figure.

STANDARD COSTING WITH ABC PRINCIPLES

Note that in Figure 3, the reference to “ABC” addresses the development of standard rates. This shows that ABC tools and principles can be utilized in the step of the overhead allocation portion of standard cost rates.

Figure 3 shows the allocation of cost center-specific indirect overhead expenses as typically allocated to the cost center using drivers like the number of cost center employees (i.e., head count) or square footage. Using these cost allocation factors for purposes other than external financial accounting would violate costing’s “causality principle.” But the standard costing process could apply ABC principles using drivers like number of machine repairs and number of product inspections to assign a certain cost center’s indirect overhead expenses. Other indirect cost centers could also leverage more meaningful drivers. Cumulatively, this will increase the accuracy of the eventual product costs.

These more accurate costs will still be used primarily for external financial reporting. The cost assignments are progressive and offer directional improvement in costing accuracy, so rather than refer to them as GAAP, to be humorous perhaps this can be referred to as “Better Accounting Principles” or “BAP.”

Consider how BAP could be applied to achieve standard costing with ABC principles behind it. Figure 6 is the long-standing schematic of ABC, the “cost assignment network.” It depicts the transformation that ABC provides as it moves costs through the stages of resources to activities to cost objects.

While the ultimate attainment of this framework is ideal, in the context of BAP, one can partially attain these benefits by leveraging ABC principles in the standard costing process by adhering to the resource to activity flow of ABC and then using those results as input to standard costing.

The revised cost assignment network in Figure 7 relates to Figures 3 and 4, in which an ABC process is undertaken for the overhead components of rate development, but the costing-to-products step still relies on standard rates. This hybrid approach can be achieved through the use of software applications that are built for cost management and allocations and then integrated with ERP processes. These applications, some of which are offered by the ERP vendors themselves, have continued to evolve over the years. They can scale and integrate to ERP modules and, as such, have been included in a wide range of operational financial processes.

This cost accounting treatment would still be in the financial accounting component of the accounting taxonomy of Figure 5. But it would contribute to a more complete application of ABC in the management accounting component. Thomas Miele, director of financial management and operations at Center Line Electric, said, “I understand the unfortunate need for balancing regulatory/GAAP reporting and ABC reporting. Melding the two concepts to work together makes all the sense in the world. I believe the authors’ proposed thoughts align well with the pure intention of IFRS [International Financial Reporting Standards], which, conceptually paraphrased, is to come up with information that is more representative of the truth. Standard costing does not do that, particularly when activity goes awry from the planned output.”

He adds, “Managers need accurate information to truly guide operations toward the corporate strategies. The rigid format of historic standard costs systems not only limits that intent with its built-in inaccuracies, it confuses many managers with misinformation. I am all for the accuracy of ABC influencing the standard costing process to a greater measure than it has to date. It is about time the industry did something that is valuable, not just compliant.”

STANDARD COSTING AND ABC: SEPARATE OR INTEGRATED?

There have been practical reasons to separate the standard costing system for external financial reporting from the internal management accounting system. A major reason is that the management accounting system (ideally powered using ABC principles) is recalculated at frequent time intervals, such as quarterly or even monthly. This is essential for managers to monitor trends on costs and profit margins as operational processes and sales volume mix change. In contrast, standard costing is typically developed one time for each fiscal year.

But current technologies enable these rates to be updated on a more frequent basis, which, if using BAP, now renders these values as being more meaningful. This starts to make the case for a more integrated approach of standard costing and ABC.

A secondary reason that has been given for separation is that a management accounting system is designed from assumptions that will differ from external compliance reporting’s GAAP. Management accounting involves modeling how resource expenses (e.g., payroll and purchases) are translated into costs (e.g., processes, work activities, products, service lines, channels, and customers). The input expenses equal the output costs, often referred to as “full absorption costing.” In contrast, external accounting with standard costing involves double-entry T-accounts and journal entries. Again, though, by using standard costing with ABC principles, an integrated approach becomes more viable.

Employee teams, managers, C-suite executives, and board directors must understand that each type of accounting system serves different purposes for different users. But there’s a benefit to mitigating these differences.

OBSERVATIONS ABOUT MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

Contrary to beliefs that the only purpose of management accounting is to collect, transform, and report data, its primary purpose is to influence behavior at all levels by providing insights and supporting decisions. A secondary purpose is to stimulate investigation and discovery by surfacing relevant information (and consequently bringing focus) and generating questions. Discussions from answering questions lead to actions and decisions.

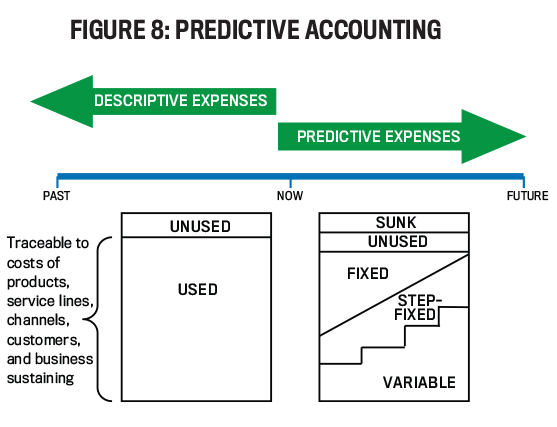

To close the gap between what accountants report and what decision makers need, there must be a shift from analyzing descriptive past-period historical information to analyzing predictive information, such as for budgets, rolling financial forecasts, and what-if scenarios. Obviously, all decisions can only impact the future because the past is already history. But there’s much that can be learned and leveraged from historical information. Although accountants are gradually improving the quality of reported history, decision makers are shifting their view toward better understanding the future.

This shift is a response to a more overarching shift in executive management styles—from a command-and-control emphasis that’s reactive (such as scrutinizing cost variance analysis of actual vs. planned outcomes)—to an anticipatory, proactive style where organizational changes and adjustments, such as staffing levels, can be made before things happen and before minor problems become big ones.

An effective management accounting system provides unit-level cost consumption rates. These are essential to calculate backward the costing system to determine the amount of future spending for resources—the number and types of employees and purchases with suppliers and contractors. Engineers refer to this as “capacity requirements planning.” For predictive costing, one must classify the behavior of the resource expenses with future changes from the past as sunk, fixed, step-fixed, or variable.

And the classifications depend on (1) the planning horizon (because capacity isn’t easily adjustable in the short term but is longer-term, such as by replacing full-time employees with temporary contactors) and (2) the type of decision the expenses and their costs are being used for. This involves incremental and marginal expenses analysis considering only the resource expenses impacted in the relevant range of the change. In a sense, management accounting becomes management economics. (See Figure 8.)

Steve McNally, IMA’s incoming 2020-2021 Chair-Elect and CFO of Plastic Technologies Inc., said, “Philosophically, to be effective management accounting and finance executives, I believe we must be business partners and strategic advisors to our cross-functional peers and CEO. But this will only happen if we have earned our seat at the table. We are, as a rule, comfortable analyzing data, trending operational and financial metrics, highlighting unusual variances, driving to root cause, and recommending solutions. With these qualities, and accurate cost and profit margin information from a cost system like ABC, we will provide meaningful decision support. And doing so will earn us that seat at the table!”

ABC-PRINCIPLED STANDARD COSTING VS. MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING’S ABC

Standard costing and ABC can coexist. Standard costing of products for external financial statutory reporting can be more accurate using ABC principles for determining annual standard costs for the financial valuation of inventory and COGS in income statements.

ABC, using different cost assignment assumptions and recalculated at time period intervals during the fiscal year, supports internal management accounting to provide managers insights to make better decisions—to create financial value. Leveraging ABC principles in standard costing improves accuracy and creates a step that culturally moves toward applying ABC at both broad and granular levels throughout the enterprise.

Ilya Gordeev, a financial analyst at Coulson Oil Company, said, “ABC to me, resembles a nerdy high schooler who always wins on a debate team but loses to a ‘standard costing bully’ in the accounting schoolyard fight, because the latter is trickier. Would ABC’s reign come when ‘the nerds’ will unite and equip themselves to share the control of ‘the schoolyard’ with the bully? I think the time is right and computing power is plentiful for ABC to be utilized more widely by companies of all sizes.”

With ABC-based information technology used for standard costing that integrates with core business transactional systems (e.g., ERP and sales management) and applying a key cost accounting principle—the causality principle that supports ABC calculations—standard costing can migrate toward being an ABC-like system. It may not be as deep and granular as a management accounting’s ABC system, but it gets closer to ABC. In so doing, we believe they should both be able to meaningfully coexist.

May 2020