Lawmakers, regulators, the accounting profession, and corporate boards have taken many notable actions over the past two decades to prevent and detect occupational fraud, including the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, the establishment of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), the issuance of Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) 99 (now AU Sec. 316), the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, and the increased inclusion of financial experts and independent shareholder advocates to public company boards.

Yet despite these efforts, occupational fraud continues to be a major problem for organizations, as the latest ACFE numbers make painfully clear. Accordingly, as a management accountant or other financial professional, you’re probably increasingly on the lookout for any additional measures that could potentially serve to detect and prevent fraud. But before you can decide on the tools you’ll need to protect your company, you’ll have to better understand the specific types of threats you’re likely to face and, more importantly, the clues that can tip you off to them.

THE PERVASIVENESS OF FRAUD

The ACFE’s 2020 Report to the Nations indicates that occupational fraud—fraud perpetrated by directors, officers, or employees of the organization—continues to be a major threat, with the largest median losses ($954,000) occurring in the area of financial statement manipulation, even though these schemes comprise just 10% of all occupational fraud.

You’re probably thinking, “That can’t happen to us. We have good internal controls.” Well, guess again. Research indicates that even organizations with strong internal controls fall victim to occupational fraud since senior management is often able to override or ignore such controls. In one such study, Vikramaditya Khanna, E. Han Kim, and Yao Lu found that the ability of CEOs to circumvent controls was frequently due to a “connectedness” they had through their employment, educational, and social networks with the very board members, auditors, and corporate officers tasked with the responsibility for governance and oversight. The authors found that this connectedness often renders internal controls ineffective, leading to increased fraud opportunity and lower levels of fraud detection. (See “CEO Connectedness and Corporate Fraud,” The Journal of Finance, June 2015, pp. 1,203-1,252.)

The significance of CEOs’ ability to frequently circumvent internal controls is underscored by a 2010 Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) study that revealed that the CEO and/or CFO were implicated in 89% of financial statement fraud cases and that almost all of the affected companies received an unqualified opinion on the last set of fraudulently misstated financial statements. So, as you can see, even with the accounting profession’s recent increases in regulation, enforcement, and penalties, people who set out to commit fraud can often still find a way.

FRAUD = OPPORTUNITY + RATIONALIZATION

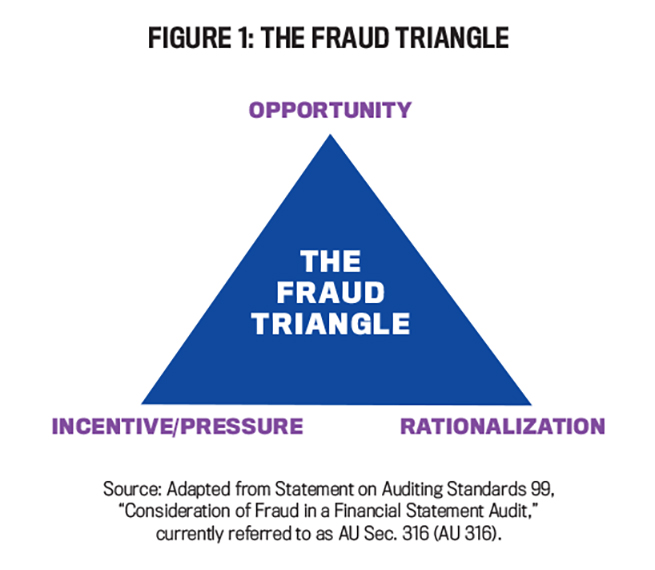

The current regulatory approach to fraud primarily focuses on reducing the “opportunity” to commit fraud through the creation of additional rules, oversight, internal controls, and punishments. While this approach certainly represents a key component of an effective fraud reduction strategy, it’s incomplete.

For instance, rather than focus on reducing the opportunities to commit fraud, detection may benefit from an increased focus on the behavioral aspects associated with fraud. And one of the most overlooked behavioral aspects is the role that rationalization plays in the propensity for individuals to commit fraud. A better awareness of its influence and impact on the act of fraud, along with the personality types that are typically prone to rationalize their transgressions, can enhance your organization’s current fraud detection efforts.

So, now that we’ve identified two of the components of occupational fraud—opportunity and rationalization—let’s examine how a third element enhances the conditions for fraud.

THE FRAUD TRIANGLE

The most common model used to study and understand fraud is the fraud triangle, as shown in Figure 1. Based on the research of criminologist David Cressey in the 1950s, it’s well established in the auditing profession, serving as the foundation of SAS 99 as well as the basis for considering fraud risk during an audit. Resting at the top of the pyramid, opportunity allows for the fraud to take place—be it a lapse in, or a complete lack of, internal controls or a top-level management override of the system. It’s defined by the opportunity to exploit someone’s trust for personal gain with low risk of being discovered.

Motivation, sometimes termed “pressure” or “incentive,” is the driving force in committing the fraud. Sometimes this force is based on needs, such as the need to pay for expensive medical treatments or for a child’s college education. In some instances, the motivation is simply a matter of greed or wanting more.

Rationalization, the third part of the fraud triangle, is the most difficult component to detect or control as it can’t be seen; it’s an internal justification for one’s actions. Rationalization allows the person who’s committing the fraud to reframe the situation to make it “acceptable” to himself or herself.

In practice, opportunity has been the prime focus of fraud prevention and detection efforts because it’s viewed as the component an entity has the most control over. Nevertheless, limiting opportunity through internal controls doesn’t provide adequate assurance that fraud won’t occur—especially since most financial statement fraud involves senior management. As noted, these individuals hold positions of power that often allow them to override and circumvent internal controls, which happened during many of the largest high-profile fraud cases, including those involving WorldCom, Qwest, Tyco, Enron, and Lehman Brothers.

This potential ability of senior management to circumvent internal controls underscores the importance of adopting additional measures to combat fraud at this level, including developing an awareness of how certain personality traits are associated with increased propensities to commit fraud. Unfortunately, those charged with corporate governance and oversight often fail to consider personality traits and instead focus primarily on internal controls when performing their duties.

Resting at the top of the pyramid, opportunity allows for the fraud to take place—be it a lapse in, or a complete lack of, internal controls or a top-level management override of the system. It’s defined by the opportunity to exploit someone’s trust for personal gain with low risk of being discovered.

Motivation, sometimes termed “pressure” or “incentive,” is the driving force in committing the fraud. Sometimes this force is based on needs, such as the need to pay for expensive medical treatments or for a child’s college education. In some instances, the motivation is simply a matter of greed or wanting more.

Rationalization, the third part of the fraud triangle, is the most difficult component to detect or control as it can’t be seen; it’s an internal justification for one’s actions. Rationalization allows the person who’s committing the fraud to reframe the situation to make it “acceptable” to himself or herself.

In practice, opportunity has been the prime focus of fraud prevention and detection efforts because it’s viewed as the component an entity has the most control over. Nevertheless, limiting opportunity through internal controls doesn’t provide adequate assurance that fraud won’t occur—especially since most financial statement fraud involves senior management. As noted, these individuals hold positions of power that often allow them to override and circumvent internal controls, which happened during many of the largest high-profile fraud cases, including those involving WorldCom, Qwest, Tyco, Enron, and Lehman Brothers.

This potential ability of senior management to circumvent internal controls underscores the importance of adopting additional measures to combat fraud at this level, including developing an awareness of how certain personality traits are associated with increased propensities to commit fraud. Unfortunately, those charged with corporate governance and oversight often fail to consider personality traits and instead focus primarily on internal controls when performing their duties.

BEWARE THE DARK TRIAD

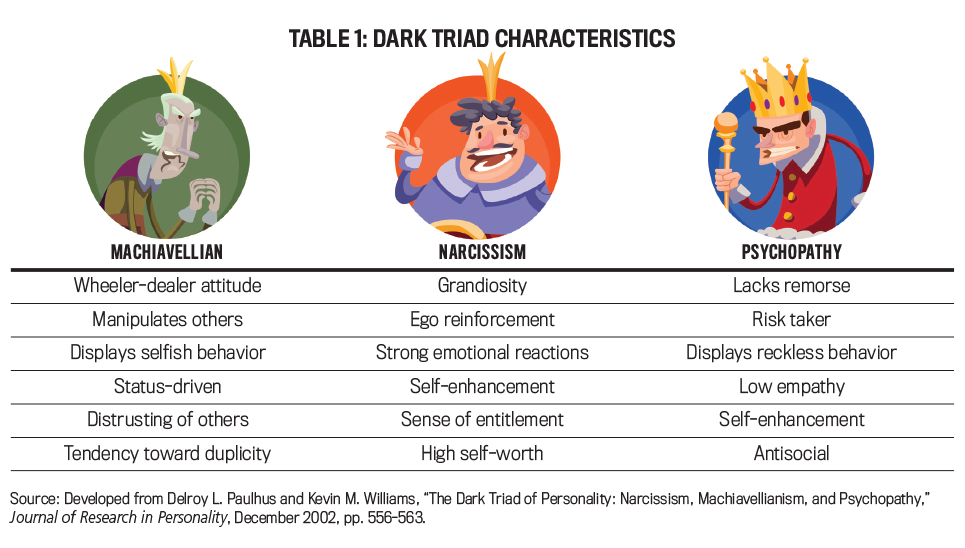

There are three personality types that psychological research has identified as having a higher tendency to rationalize: Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy. Table 1 lists some of their typical behavioral characteristics. Individuals with these three personality types may be more likely to participate in unethical behavior, including risky financial endeavors.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Machiavellians are known as the manipulative personality type due to their ability to use soft tactics that are acceptable in society, including humor, appearance, or compliments, to gain favor. Machiavellians don’t feel any sense of remorse for manipulating others to reach a goal; in fact, they often enjoy it. Manipulation is simply viewed as a means to accomplish the desired outcome, which is often to exert control and gain status.

Instances of manipulation can be seen in many well-known fraud cases. For example, WorldCom CFO Scott Sullivan manipulated the accountants he involved to certify the company’s fraudulent journal entries. According to former WorldCom VP Cynthia Cooper, in her book Extraordinary Circumstances: The Journey of a Corporate Whistleblower, Sullivan appealed to employees’ loyalty, thanked them for their hard work, and reassured them the entries were for “one-time” errors that would correct themselves in the next quarter, even stating, “What you want to do, if you would, is stick with the company long enough to get…the situation fixed.”

In addition, impulsivity traits are different for a Machiavellian personality in comparison to a psychopath. Machiavellians are able to control impulsive behavior, which are actions that appear to be taken without any foresight or without regard of the consequences. They instead reserve this tendency for use when it’s most beneficial to them, maintaining the ability to quickly adapt and make decisions.

This personality is also driven by a need to increase power and authority over others as a means of enhancing their status while still remaining much more grounded in their sense of self when compared to the other dark personality types. In an article published in the Journal of Applied Psychology, Ernest O’Boyle, Donelson R. Forsyth, George Banks, and Michael A. McDaniel summarize three core principles of Machiavellians: They believe that manipulation tactics used to deal with others are effective; they hold a distrustful view of human nature; and they place expediency well above principle. (See “A Meta-Analysis of the Dark Triad and Work Behavior: A Social Exchange Perspective,” Journal of Applied Psychology, October 2011, pp. 557-579.)

Narcissism is characterized by grandiosity, ego reinforcement, a sense of entitlement, high self-worth, and strong emotional reactions. Narcissists also tend to demonstrate self-enhancement when comparing themselves to others, which is used to better improve their standing when comparing themselves to friends or strangers. The desire to appear better than other individuals drives their behavior. Narcissists and psychopaths display a similar amount of self-enhancement, though narcissists have a better grasp and ability to use this trait in a beneficial manner.

Psychopathy shares some of the same traits as the other two personality types; however, there are some key differences. Psychopaths are distinguished by a willingness to take risks, having little empathy for others, and possessing low levels of anxiety. These characteristics may also be indicators of an ability to perpetrate fraud, due to a psychopath’s overall lack of remorse. Yet while this is the most destructive personality type of the dark triad, psychopaths typically possess antisocial behaviors and lack the interpersonal skills required for success in the workplace.

FINE-TUNE YOUR RADAR

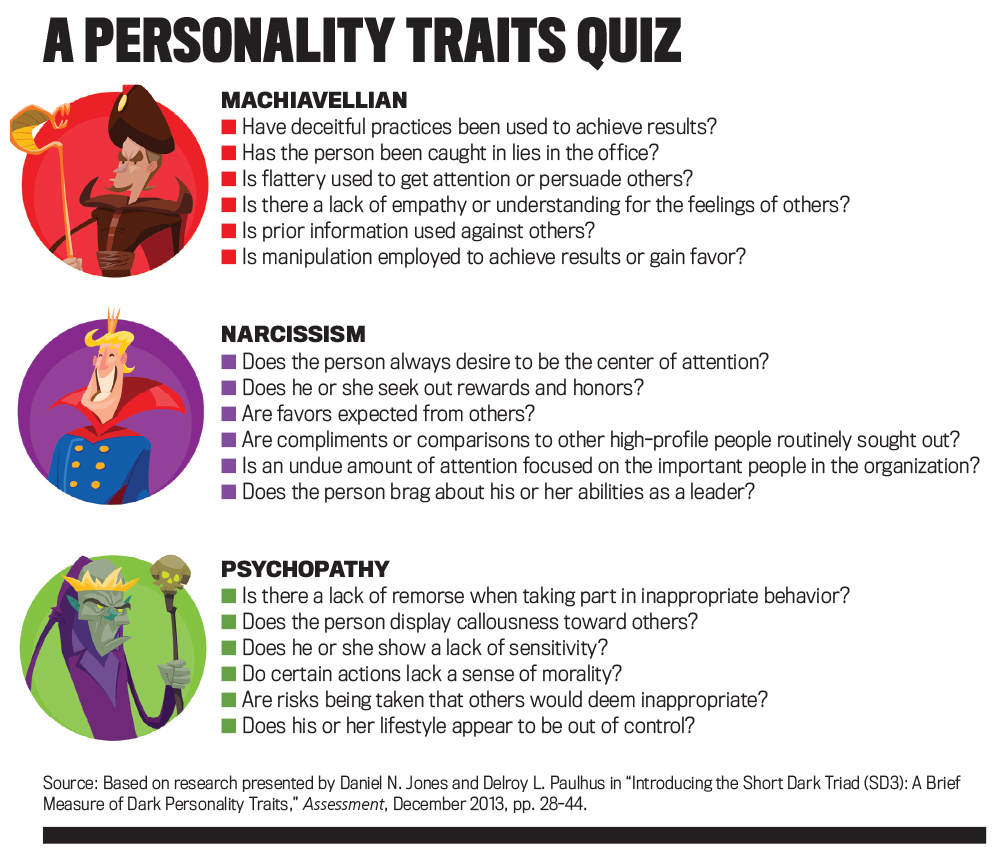

If you’re a management accountant or other financial professional involved in oversight and corporate governance, you should be aware of the key traits associated with the dark triad personality types, especially those that are associated with an increased propensity for fraudulent behavior. This focus on personality type and traits should be a component of the fraud risk assessment and oversight within your company. Knowing how these traits facilitate the rationalization of fraud could help in further refining systems and controls to deter or prevent fraudulent action.

These personality types also shouldn’t be overlooked when evaluating individuals for promotion into senior leadership positions. In fact, a review of several recent PCAOB inspections of audit firms found many reports to be deficient in these important safeguards. Identifying and including personality types as part of the risk assessment may improve the professional skepticism of those reviewing corporate financial statements.

Sridhar Ramamoorti and Barry Epstein indicate that “a focus by auditors on personality factors is unlikely to go unnoticed by potential dark triad personality types, and the heightened ‘perception of detection’ may itself potentially serve as a deterrent” (see “Today’s Fraud Risk Models Lack Personality,” The CPA Journal, March 2016).

Fortunately, many red-flag behaviors are embedded in these personality traits. For instance, the ACFE studies indicate senior management perpetrators demonstrated control issues, were unwilling to share duties, demonstrated a wheeler-dealer attitude, and were suspicious and defensive. Cooper, the WorldCom whistleblower, says these same behaviors were evident in the actions of both Sullivan and Bernard Ebbers, the company’s former CEO, who died in February 2020 after a lengthy prison term. Ebbers, Cooper says in her book, attended to almost every detail of the organization (control issues) and was very much a wheeler-dealer in the industry, as his nickname the “Telecom Cowboy” attested to.

While you should be so lucky not to have a Scott Sullivan or a Bernie Ebbers on your company’s payroll, is there a way to tell whether someone in your organization might potentially take part in any fraudulent acts? Nothing’s foolproof, of course, but the Personality Traits Quiz (below) can help you with this assessment of yourself and others. In addition, Daniel N. Jones and Delroy L. Paulhus have devised a test (bit.ly/2zUsh6G) that can be used for self-assessment and to gain further insight into how to detect dark triad personality types.

Click to enlarge.

STAY VIGILANT

Awareness is the key to managing the potential negative consequences associated with dark triad types. If you identify some of these traits in yourself, don’t be overly concerned! Many effective leaders have elements of these personality types to varying degrees. It is, however, important to implement practical strategies to mitigate these traits from becoming too dominant, which can lead to negative consequences.

The first strategy involves proactively identifying and carefully reflecting upon the potential near and long-term consequences that each decision alternative will likely have on others, your organization, and your professional reputation. Engaging in this type of intentional reflection prior to actingis an effective technique to mitigate potential negative consequences.

Second, seek advice from respected and trusted colleagues within and outside your organization prior to making key decisions. Gaining a number of perspectives will help guide you to make better decisions. Third, talk with leaders who possess personality and leadership traits that may help balance your personality. For example, including input from team members who follow a servant-leadership style—in which the main goal of the leader is to serve—and demonstrate high levels of empathy will be very useful.

Finally, take the long view in working on other elements of your personality to ensure your dark triad personality traits don’t become dominant. For instance, you may want to make a point of interacting more with leaders within your organization who best personify the positive traits you’d like to see in yourself.

What if an important leader in your company—or perhaps even your own manager—seems to be demonstrating dark triad personality traits? First, do everything you can to safeguard your own reputation. Research shows that financial professionals involved in fraud were often led down the path by a superior with a dominant dark triad personality type. Depending on the severity of the situation, you may consider setting boundaries directly with the individual, reporting continued incidents to human resources, or, in more serious situations, using both internal and external whistleblower programs to protect both yourself and the organization.

AWARENESS AS A DETERRENT

It’s important to understand that possessing dark traits is not an absolute indicator of fraud. Traits such as an achievement orientation (which is related to status-driven), professional skepticism (which is related to distrust of others), and self-confidence (which is associated with high self-worth) can actually have positive impacts on career success and are important for achievement within organizations. While understanding these personality traits and observing them may be a tool to better understand the rationalization component of fraud, this approach shouldn’t be used to target individuals, but rather as a means to alter or avoid questionable behavior to ensure that fraud doesn’t occur.

Awareness of these behavioral traits could be used to help anticipate problem areas and develop and assess controls and processes to prevent fraudulent behavior. It’s also critical for professionals who serve in oversight, governance, and management roles to understand their own propensity to rationalize behavior. Quite simply, fraud begins at the individual level. As Cynthia Cooper wrote in her book, everyone must “guard against being lulled into thinking you’re not capable of making bad decisions.”

In short, don’t avoid turning the spotlight on yourself every so often. Personal self-reflection and evaluation of these traits are a healthy way for professionals like yourself to avoid potential negative consequences before the opportunity to commit a fraudulent act arises. Your reputation—and by extension, your livelihood—may depend upon it.

June 2020