The competition is named in memory of Carl Menconi, who held leadership positions in IMA for many years and served as chair of the IMA Committee on Ethics. The objective of the competition is to develop and distribute business ethics cases with specific application to management accounting and finance issues and that use the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice as a reference or guidance tool.

The winning case and teaching notes are available for use in a classroom or business setting. IMA academic members can access and download the teaching notes from the Academic Teaching Notes library via the IMA Educational Case Journal section of IMA’s website: www.imanet.org/educators/ima-educational-case-journal.

Emily Johnson was looking out her office window at the snow on the mountains and reflecting on the last two months. It had been a whirlwind few months in her role as CFO of Southwest Hospice, a regional nonprofit hospice with approximately 200 employees, and Emily found herself facing a dilemma regarding next week’s meeting of the board of directors.

Emily had begun working at Southwest Hospice in early December. Prior to that, she had spent seven years as the CFO of SGI, a national educational nonprofit. Emily was proud of how she helped SGI prosper during a recent financial downturn. She earned a reputation for providing accurate and reliable cash flow projections to SGI’s national board of directors. That reputation had been an important factor in the Southwest Hospice board hiring Emily.

In fact, the chair of the board had told her that the board was excited that her extensive financial experience would complement the background of Southwest CEO Michael Anderson, who had a degree in social work. During Michael’s five years as CEO of Southwest Hospice, he relied heavily on Frank Williams, Southwest’s former CFO, to manage the organization’s finances.

Emily had been excited to join Southwest Hospice. Her father had relied on hospice care in the last days of his life, and she knew how important the services offered by hospices were to the dying and their families. Emily believed that by using her knowledge and experience, she could help Southwest Hospice continue to grow.

In recent years, Southwest had experienced slow, steady growth without any cash flow problems. Emily knew that within two months of starting the job, she would be expected to complete the annual audit and prepare the next year’s cash projections for the board of directors. She hadn’t been worried, however. During her job interview, Michael told her that Southwest’s financial records were in excellent order.

SIGNS OF TROUBLE

By the end of December, her first month of employment, Emily realized that something was wrong. She had been shocked to discover that no one had completed the month-end closing process nor reconciled any of the bank statements for the last 12 months. The year-end balance in the cash account wasn’t enough to pay the outstanding bills or payroll. Accounts receivable were at an all-time high, and Southwest’s investments showed significant losses.

No one knew that Frank, the former CFO, had neglected the hospice’s finances during his last year of employment. Apparently, Frank had taken advantage of Michael’s lack of financial knowledge and spent most of his time secretly looking for his next job. When Frank left Southwest for a CFO position at a regional hospital, he told Michael that the hospice was in good financial shape.

When Emily realized the extent of the accounting problems, she asked Michael to postpone January’s annual audit. Because Frank had told Michael and the board of directors that the accounting records were in order, Michael refused Emily’s request. With less than two weeks to prepare for the audit, Emily was unable to clean up the accounting records before the beginning of the audit. The auditors complained to Michael about Emily’s poor job performance.

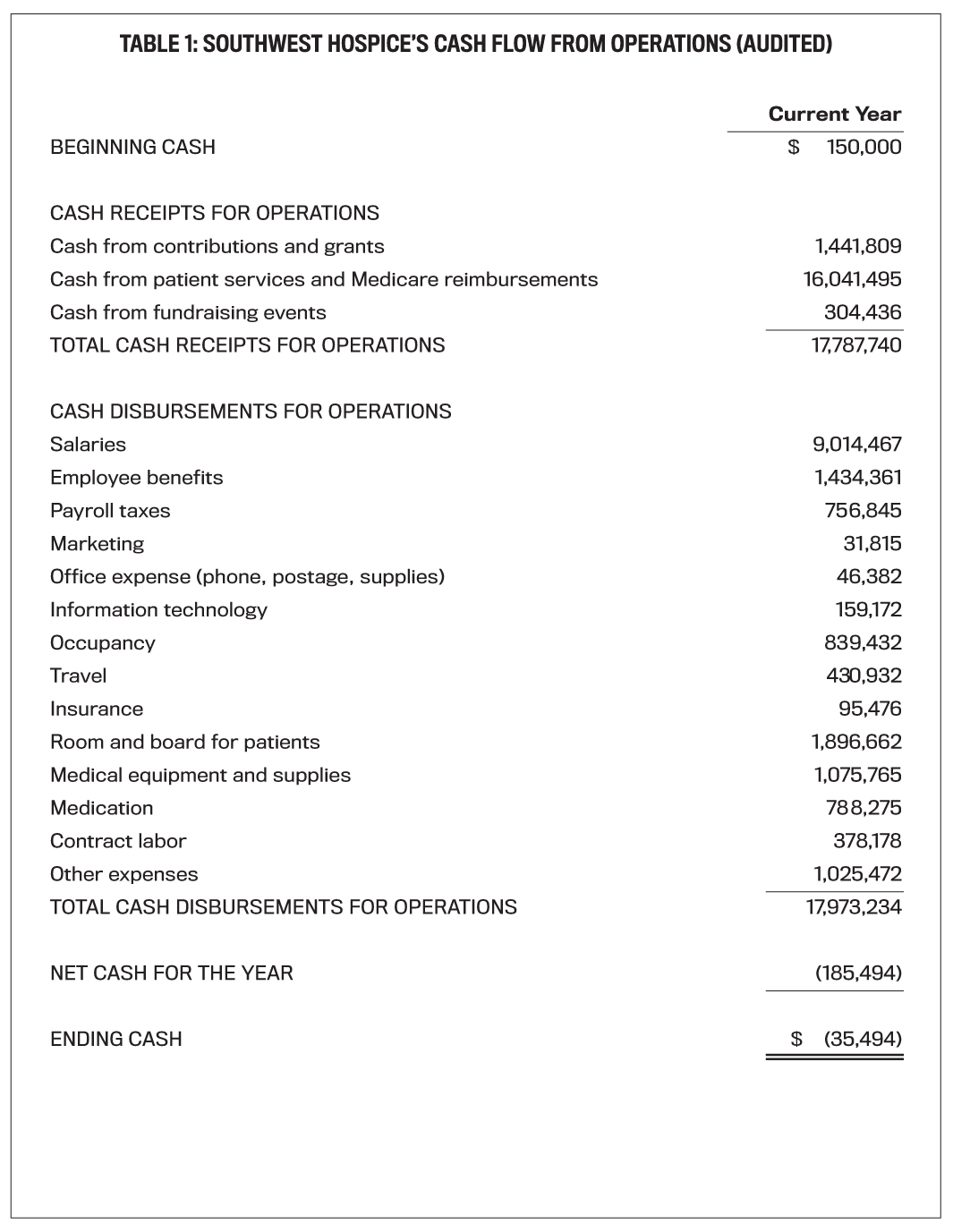

When the audit was finished, Emily thought her nightmare was finally over. She had managed to clean up the mess left by the prior CFO. Yet she also knew that Southwest had run out of cash (see Table 1). Now she had to prepare the cash flow projection for next year and inform the board at the meeting next week of potential future cash flow problems.

Click to enlarge.

NEXT YEAR’S PROJECTIONS

As always, Emily began her cash flow projections by realistically looking at the cash inflows. Southwest Hospice hadn’t planned to increase private billing and, although Medicare reimbursements might increase, cash from patient services and Medicare reimbursements would most likely remain the same or even decrease by up to 0.5%. Cash from fundraising events was also unlikely to change. With the organization’s continued growth, however, Emily believed that cash from contributions and grants would increase about 4% in the coming year.

Turning her attention to the cash disbursements, Emily knew that part of the reason Southwest was experiencing a negative cash balance was that last year Michael had convinced the board of directors to hire an experienced palliative care doctor for a new part-time medical director position. Strategically, hiring an experienced palliative doctor was important for future growth, but it had severely hampered cash flow.

Given this new hire, salaries and payroll taxes would increase approximately $435,000 and $23,000, respectively, for the coming year. Employee benefits, however, were likely to drop 2% to 3% due to the annual healthcare benefit negotiations with the insurance company. Although Southwest usually managed its growth by hiring contract labor, Emily believed that more careful staffing would allow her to drop contract expenses by about 20%. Travel expenses and medication expenses were expected to remain about the same.

Emily continued to look for areas where she could cut costs. She planned to renegotiate the property and fire insurance policies and believed she could cut costs in the insurance category by about $15,000. Emily also believed in upgrading the computers and other technology. She believed a modest investment of $21,000 in information technology would allow her to cut about 15% of office expenses and about 5% of other expenses.

Unfortunately, Emily recognized that some expenses were bound to increase as Southwest continued to grow. She anticipated that occupancy would increase between 1% and 4%, while room and board for patients would either stay flat or increase modestly by up to 1% in the coming year. To sustain growth, however, a 15% investment in critical medical equipment and supplies would be necessary. In addition, Southwest Hospice was planning to increase the marketing and advertising budget about 55% to 60% for the coming year.

THE CEO’S REQUEST

Emily was looking over her preliminary cash flow projection for next year when Michael knocked on her office door with a concerned look. Michael told Emily that he and the board of directors were very concerned about her poor performance with the audit. They were beginning to wonder whether Emily was the right person for the CFO position. He noted that Frank was always upbeat and optimistic about Southwest’s future.

Michael felt it was important for Emily to demonstrate her optimism and commitment to Southwest Hospice by projecting a positive cash flow trajectory. He told Emily, “I noticed in your preliminary cash flow projection for next year that you didn’t include the $1 million grant from the Community Foundation that we’re expecting this year. I believe you should include that grant in the cash flow projection you present at next week’s meeting of the board of directors. I know we didn’t get the grant last year, but, as you know, the committee needs to see a sizable cash surplus before they can approve my new salary.” Michael then left her office quickly before Emily could say anything.

When Michael hired the experienced palliative doctor last year, he told the board of directors that it would need to double Michael’s current $250,000 salary (plus associated payroll taxes of $20,000) so that he would continue to be the highest-paid Southwest Hospice employee. Emily thought that doubling Michael’s salary would make him one of the highest-paid CEOs in the country among hospices of similar size and revenue as Southwest. Yet the board of directors seemed more than willing to grant Michael’s request as long as Southwest continued to generate healthy cash reserves.

A DIFFICULT SITUATION

Michael’s message to Emily was clear. She believed her job might be on the line depending on what she told the board at next week’s meeting. Emily had no problem being optimistic about Southwest Hospice’s future, but she was surprised that Michael asked her to include the grant money in her cash flow projection. Southwest hadn’t received the grant last year, and it was clearly going to be more competitive this year.

Yet Emily knew cash flow projections were subjective. There were no accounting standards to govern what should or shouldn’t be included in projections. She wondered whether the board of directors would even question the inclusion of the grant—especially if the board was used to Frank’s optimism about cash flow projections. At the same time, she also knew that the board hired her because she was a CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) and CPA (Certified Public Accountant). She had a reputation as someone who is trustworthy and able to prepare reliable cash flow projections.

Emily also thought about what could happen if she told the board of directors about Southwest’s cash flow problems. Michael could easily use her poor job performance with the annual audit as an excuse to fire her. With a family of five young children to support, she couldn’t afford to be unemployed right now. Two of her children had expensive medical conditions, and she needed the health insurance coverage.

Emily thought that Michael would probably tell the board of directors to ignore her cash flow projection because of her poor job performance. Since several board members were Michael’s close friends, Emily realized that the board could easily approve Michael’s salary increase regardless of her input. Because she was new to Southwest Hospice, perhaps she should comply with Michael’s request. It would be easier to confront cash flow problems next year once the board of directors got to know her.

As Emily gazed at the mountains and pondered her situation, she was still uncertain about what to tell the board of directors. Should she hope for the best and say that Southwest Hospice will have the cash to double Michael’s salary? Should she disclose the cash flow problems knowing that Michael might fire her and still get the board of directors to recommend approval of his salary request? Could Emily figure out a way to present the cash flow projection that both highlighted her optimism and support for Southwest Hospice while presenting the board of directors with an accurate cash picture?

QUESTIONS

- Identify the personal pressures as well as the organizational culture and ethical issues involved in Emily’s preparation of the cash flow projection for next week’s board meeting at Southwest Hospice.

- As a CMA and member of IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants), Emily must abide by the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice. What principles and standards from the IMA Statement do you believe are the most relevant for Emily to consider?

- (Optional) GuideStar.org is a comprehensive source of information on nonprofit organizations. Use the website to prepare an analysis of hospice CEO salaries by size (revenue).

- Using the information in the case, prepare the final cash flow projection (to the nearest $10,000) that you think Emily should present to the board, along with any talking points that you think should be included. For example, should Emily include the grant application in the cash flow receipts? Should Emily address Michael’s salary increase directly or indirectly? Should Emily take a hard stand on the cash flow problems?

- This case is based on a real but disguised situation. What do you think happened?

July 2020