A provision addressing the demand for more accountability within the context of executive compensation is the Rule 10D-1 “clawback” under the Dodd-Frank Act (P.L. 111-203) with which the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed a recovery policy in the event of accounting restatements. Specifically, the rule introduces a new listing standard for publicly traded companies that, when adopted, would require:

- That current and former executive officers return incentive-based compensations awarded within three years prior to an accounting restatement, regardless of whether a misconduct occurs or whether the executive is “at fault,” and

- That companies disclose in their annual reports the recovery procedures and actions under those policies.

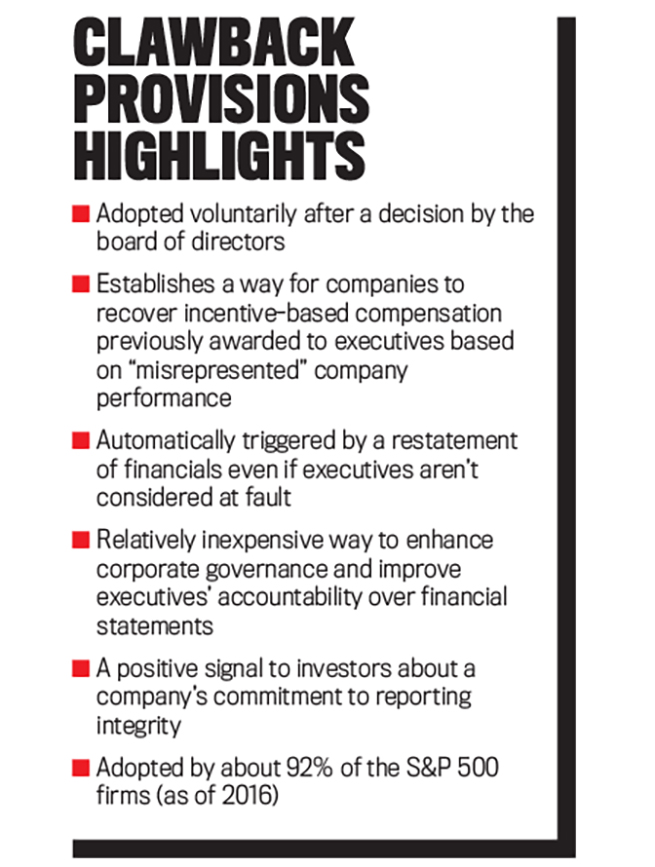

Although the proposal was made in 2015, it still hasn’t been finalized, and companies aren’t mandated to adopt Rule 10D-1 or a similar policy. Though it isn’t required, companies can choose to adopt clawback provisions voluntarily—and many have done so.

Starting in 2006, companies such as AT&T, Boeing, CME Group, Dell, Gap Inc., General Electric, General Motors, Home Depot Inc., and others began to adopt clawback rules in order to improve corporate governance and better align executives’ incentives with the goals of the organization. According to the Corporate Library Database, which collects voluntary clawback information from company proxy statements, close to 50% of the Russell 3000 nonfinancial companies had voluntarily adopted such a policy by the end of 2014. (Note that financial institutions are subject to mandatory clawback as part of the Economic Recovery Act of 2008 in return for accepting assistance from the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP.) And a 2017 Equilar report on executive compensation and governance outlook found that 92% of the S&P 500 disclosed a clawback policy in 2016 (bit.ly/2LeZ9K9).

Despite voluntary clawback provisions having been in effect since 2006, actual litigation has been sparse. In a 2017 working paper on clawback provisions, Ilona Babenko, Benjamin Bennett, John M. Bizjak, and Jeffrey L. Coles examined a sample of 242 companies that voluntarily adopted clawback provisions and later restated earnings, which should have triggered a clawback. They found that only three companies disclosed a clawback activation in their proxy statements. One example of clawback enforcement mentioned is Warnaco Group, Inc. In September 2006, the company filed a restatement of its 2005 financial results and accordingly reduced bonus awards for its CEO, CFO, and one group president for the 2006 fiscal year in the amounts of $45,600 (4.7% of total bonus), $22,440 (6.2%), and $51,744 (35.6%), respectively.

In a more recent case, Hertz Corp. v. Frissora, filed in March 2019, Hertz sought to recover approximately $70 million in incentive compensation paid to former CEO Mark Frissora, former CFO Elyse Douglas, and former General Counsel John Jeffrey Zimmerman in connection with a financial restatement following the company’s clawback policy.

Adopting voluntary clawback provisions can have a number of accounting implications—not just for the accounting and finance professionals within the company, but to others as well, including auditors, financial analysts, and investors. Three key areas that are affected include the contracts that contain bonus repayment requirements, evaluating company performance, and interpreting management’s earnings expectations. Let’s take a look at each.

AN EFFECTIVE CLAWBACK PROVISION

Consider the Boeing Company’s voluntary clawback provision reported in its 2006 proxy statement filed on March 23, 2007:

In 2006, the Board of Directors adopted an executive compensation clawback (“recoupment”) policy, which is now a part of the Company’s Corporate Governance Principles. Under the Company’s recoupment policy, the Board must, in all appropriate circumstances, require an executive officer to reimburse the Company for any annual incentive payment or long-term incentive payment to the executive officer where: (i) the payment was predicated upon achieving certain financial results that were subsequently the subject of a substantial restatement of Company financial statements filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission; (ii) the Board determines the executive engaged in intentional misconduct that caused or substantially caused the need for the substantial restatement; and (iii) a lower payment would have been made to the executive based on the restated financial results. In each such instance, the Company will, to the extent practicable, seek to recover from the individual executive the amount by which the individual executive’s incentive payments for the relevant period exceeded the lower payment that would have been made based on the restated financial results.

The provision appears comprehensive at first glance, yet there are several unanswered questions: Who is and who isn’t “an executive officer” for purposes of the Boeing clawback rule? After a restatement is filed, how much time does the company have to activate a clawback, and from how far back can it reclaim money? What criteria need to be met for the board of directors to prove an executive intentionally engaged in misconduct, and what is the standard used to define a “substantial restatement”? If these questions are left unanswered, the board can have a rather substantial degree of discretion in determining that improper activities weren’t, in fact, meaningful enough to activate a clawback.

Accountants and auditors should be concerned about these questions because they might be consulted to provide a professional opinion about restatements and their potential impact on compensation clawbacks. Internal auditors who are tasked with auditing executive compensation and benefit plans are directly affected by clawbacks because of the relationship between corporate governance, executive compensation, and various risk factors. This can be challenging in situations when an internal auditor discovers that his or her boss’s compensation package isn’t structured in the best interests of the organization and the owners of the company.

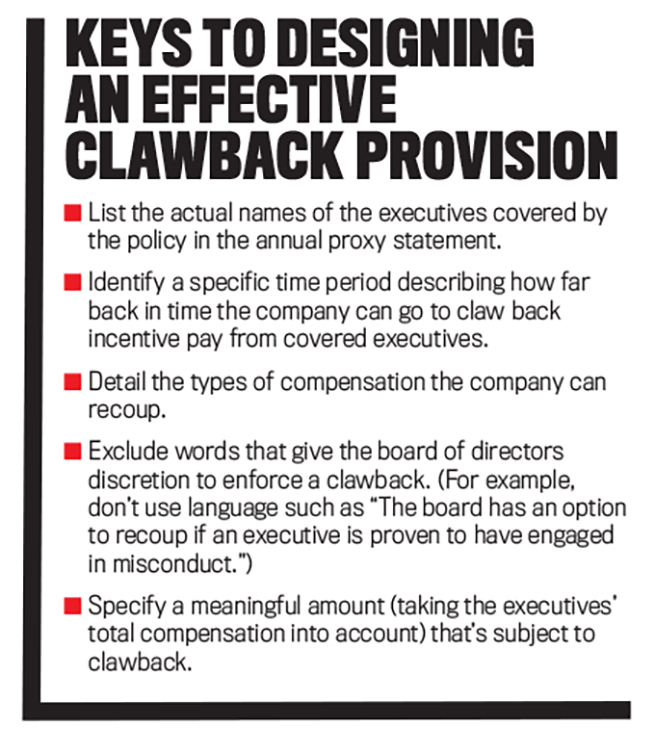

A study by Michael H.R. Erkens, Ying Gan, and B. Burcin Yurtoglu identified several aspects that companies should include to strengthen the clawback policy, including specifically naming the executives covered by the policy, identifying the time period for how far a company can go back in time to “claw back” the incentive pay from the covered executives, detailing the types of compensation the company can recoup, and excluding words that give the board discretion to enforce a clawback, such as “the Board has an option to recoup if an executive is proven to have engaged in misconduct.” (For more, see “Not All Clawbacks Are the Same: Consequences of Strong Versus Weak Clawback Provisions,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 2018.)

In addition, the proportion of the amount of compensation subject to a clawback relative to an executive’s total compensation is another key to a strong policy. Clearly the higher this proportion, the more effective the policy will be. Giving the board a deadline to enforce the policy is another critical element.

Here’s what the provision could look like if it included those elements (added text is in bold, and deletions are shown in strikethrough text):

In 2006, the Board of Directors adopted an executive compensation clawback (“recoupment”) policy, which is now a part of the Company’s Corporate Governance Principles. Under the Company’s recoupment policy, the Board must, in all appropriate circumstances, require the NEOs [Named Executive Officers] included in the Summary Compensation Table on page 35 of this proxy statement to reimburse the Company for any Annual Incentive Award, Performance Award, and Stock Options Award to the executive officer (up to 20% of his/her total annual compensation) where: (i) the payment was predicated upon achieving certain financial results that were subsequently the subject of a substantial restatement of Company financial statements filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission; (ii) the Board determines the executive engaged in intentional misconduct that caused or substantially caused the need for the substantial restatement the payment was received within three years prior to the financial restatement; and (iii) a lower payment would have been made to the executive based on the restated financial results. In each such instance, the Company will, to the extent practicable, have two years from the restatement’s filing date to seek to recover from the individual executive the amount by which the individual executive’s incentive payments for the relevant period exceeded the lower payment that would have been made based on the restated financial results.

This revised version eliminates potential ambiguity related to the board’s procedures and actions in order to enforce the clawback policy in case of a restatement and, therefore, should constitute a stronger corporate governance policy.

PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

Research studies have examined the impact of adopting a clawback provision. For example, in 2012, Lilian H. Chan, Kevin C.W. Chen, Tai-Yuan Chen, and Yangxin Yu shared findings in the Journal of Accounting and Economics that the number of restatement filings decreases after a company adopts a clawback policy. They also provide evidence that auditors reduce effort in auditing clawback clients relative to clients without clawbacks.

And Mai Iskandar-Datta and Yonghong Jia found that the market responds positively to companies after they make an announcement about voluntary clawback adoption (“Valuation Consequences of Clawback Provisions,” The Accounting Review, 2013). The impact was especially noticeable for companies that have previously filed restatements, suggesting that investors as a whole view clawbacks as an effective corporate governance mechanism to curb earnings management.

Yet merely having a clawback provision doesn’t guarantee that there won’t be any errors or financial statement manipulations. Auditors must apply the same diligence when auditing a company’s financial statement whether or not a clawback provision was adopted. For instance, Diane K. Denis found that the correlation between clawback adoption and the observed subsequent reduction in restatements could be explained by executives being more reluctant to file restatements and admit mistakes after a clawback provision is adopted (“Mandatory Clawback Provisions, Information Disclosure, and the Regulation of Securities Markets,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 2012).

In fact, in an experimental study where corporate executives were asked to decide whether they would agree with the auditors in filing a restatement, results show that executives are reluctant to do so when a high portion of their pay is subject to a clawback, especially when facing an auditor with relatively less industry specialization, training, and overall experience (Jonathan Pyzoha, “Why Do Restatements Decrease in a Clawback Environment? An Investigation into Financial Reporting Executives’ Decision-Making During the Restatement Process,” The Accounting Review, 2015).

Furthermore, in several cases, higher pay followed the adoption of the clawback provision. For instance, Ed Dehaan, Frank Hodge, and Terry Shevlin compared compensation for companies with clawbacks and those without and found that total compensation increases after a company adopts a clawback policy and that this increase is largely driven by higher base salary as opposed to incentive compensation. Such changes in the executive compensation structure counteract the effect of clawback by shifting away from the “clawable” portion bonuses and stock options and replacing them with base salaries (“Does Voluntary Adoption of a Clawback Provision Improve Financial Reporting Quality?” Contemporary Accounting Research, 2013).

Auditors should look for clues in the qualitative factors, such as how close the company is to meeting its earnings targets. Narrowly beating an earnings target could be an indicator for financial statement manipulation. Both internal and external auditors need to pay attention to the language used in a company’s clawback policy to assess whether the clawback is set up only in appearance.

EARNINGS GUIDANCE

In addition to accountants and auditors, investors and analysts should also be concerned with the presence of clawback provisions. One of this article’s coauthors, Yuanyuan (Savannah) Guo, conducted an academic study that shows that voluntary clawback adoption is accompanied by unanticipated changes in company and investor behaviors. Companies with clawback provisions are more likely to issue pessimistic quarterly earnings guidance to lower analysts’ expectations, which is one commonly seen practice to increase the company’s chance of meeting street earnings.

For example, assume that ABC Corp. has a voluntary clawback provision in place while XYZ Corp. doesn’t. The analysts’ consensus forecast for both companies’ earnings per share (EPS) is $0.50. ABC issues an earnings forecast of $0.46 per share, which may cause the analysts to revise and lower their forecasted earnings to $0.48 per share—an easier target for the company to achieve than the initial analyst-forecasted EPS of $0.50. XYZ, on the other hand, doesn’t provide such pessimistic guidance; thus, the analysts’ forecast for XYZ likely isn’t revised. The only difference between the two corporations in our example is that in the case of ABC, the executives are also worried that they may have to repay their bonuses in case of restatements.

Interestingly, manipulating an EPS forecast doesn’t trigger a clawback; a clawback is only triggered by a restatement. Yet clawback companies still try to influence earnings forecasts. It’s estimated that companies with clawbacks are associated with an 18.72% higher likelihood of issuing downward earnings guidance than those without clawbacks. This suggests that having a clawback provision encourages executives to find creative ways to meet earnings expectations without triggering a clawback. Practices like these defeat the clawback’s actual purpose of enhancing financial reporting quality and accountability.

The research also shows that the stock market rewards companies with clawbacks less for meeting earnings targets relative to companies without clawback provisions. To illustrate, let’s resume the previous example. Assume that the final analysts’ forecast for ABC is $0.48 per share and that it remains $0.50 per share for XYZ. Also assume that on earnings announcement day, ABC reports an EPS of $0.49 and XYZ reports an EPS of $0.51—both narrowly beating earnings targets by $0.01.

Theoretically, since both companies beat their earnings goals by the same amount, the stock market should treat the two equally and the stock prices should increase about the same amount to reflect each company’s earnings news. But analysis shows that stock prices are on average 1.52% lower when companies like ABC announce they’ve narrowly beaten earnings targets compared to companies like XYZ over a 90-day period. This translates to a more than 6% difference in investment returns without compounding.

Recall that ABC has a clawback policy while XYZ doesn’t. ABC also manipulated analysts’ forecasts. From this example, we infer that, because clawbacks curb only potential book earnings manipulation but not forecast manipulation, investors can’t differentiate between a really good result (i.e., XYZ) from a result that only looks good because the numbers were manipulated (i.e., ABC). This potentially explains why the stock prices of ABC wouldn’t increase as much as those of XYZ.

At the end of the day, what does this mean for the investors? In the short term, under similar earnings conditions, shareholders of companies with clawback provisions may not enjoy as much investment return as stock owners of companies without clawback provisions due to the discounted stock premium around earnings announcements. In the long run, investors should focus less on “the numbers game”—how many cents a company beat its quarterly earnings target—and focus more on the company’s strategic planning, corporate governance, and long-term growth potentials.

BROAD IMPLICATIONS

There are a number of accounting and financial implications for companies that voluntarily adopt a clawback provision. Understanding and being able to recognize the impact these provisions might have on company performance and reporting is of critical importance for accountants and financial professionals in business. Not every clawback policy is created the same, and there are several aspects that companies should include to strengthen theirs to achieve the primary goal. Internal auditors and corporate accountants should pay attention to whether clawback provisions are designed in line with the best practices in order to improve overall corporate governance.

The impacts extend beyond those within companies as well. External auditors need to understand how clawback provisions may affect managements’ incentives and reactions to potential restatements or errors. And analysts and investors should understand that management earnings guidance behavior might be changed after a clawback policy is adopted. Rather than focusing on “the numbers game” of earnings guidance, it’s the company’s strategic planning, corporate governance, and long-term growth potential that are the keys to prolonged success.

January 2020