One topic in particular that sets the stage for students to become impactful professionals in the workplace is Lean thinking, which is a combination of emphasizing quality, understanding costs, and minimizing waste and excess inventories. Lean thinking capitalizes on the ingenuity of employees, customers, and other stakeholders to improve operations. It’s captured in five principles: value, value stream, pull and flow, empowerment, and perfection.

As the IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) Statement on Management Accounting (SMA) Business Performance Management—Lean Enterprise Fundamentals describes it, “Lean processes provide a way to do more with less—less human effort, less equipment, less time, and less space—while coming closer and closer to providing customers with exactly what they want, when they want it, where they want it, and at a price that meets their cost/value expectations.” (The SMA can be found at bit.ly/2Dg0oI4.)

At my university, cost accounting students have studied Lean techniques, applied them to departments at their school as well as to local establishments, and then created solutions to add value and minimize waste. With this in mind, I’ll demonstrate how college students—and practicing management accountants or financial professionals—can think creatively by thinking Lean.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

ADDING LEAN THINKING TO THE CLASSROOM

Despite the importance of Lean in operational performance, Joseph F. Castellano and Ron Burrows, in a 2011 Management Accounting Quarterly article, found that the most popular managerial and cost accounting textbooks barely mentioned Lean techniques, and the majority of the professors who covered Lean didn’t supplement the text with actual published cases or projects. In searching for ways to incorporate Lean principles in the classroom, I confirmed what Castellano and Burrows found—that there was a lack of guidance on how to teach Lean in the classroom and few supplemental teaching resources available. (For more on this topic, see “Relevance Lost: The Practice/Classroom Gap,” Management Accounting Quarterly, Winter 2011.)

Moreover, if I were going to ask my students to think Lean, I knew that they needed to be engaged in an actual entity in order to properly evaluate it. The reason for this is that, according to research, employers believe that applied learning in real-world settings will significantly improve how well students are prepared for their careers. Even today, while more resources have been published on Lean for educators to use, they’re almost always about organizations with which the students have no direct interaction or experience.

The first iteration of my Lean project began in the fall 2012 semester, after I found three resources that were particularly useful in designing it. The first two were IMA SMAs published in 2006: Accounting for the Lean Enterprise: Major Changes to the Accounting Paradigm and the previously mentioned Business Performance Management—Lean Enterprise Fundamentals. They helped me to create lecture materials that cover the Lean principles not found in the textbooks.

The SMAs also addressed how Lean thinking links to other strategic concepts that I covered in class: strategy, performance measures, and the value chain. I realized then that this project would not only emphasize Lean thinking but become a vehicle to link together many of these concepts.

The third resource was a 2009 article from The Wall Street Journal titled “The Latest Starbucks Buzzword: ‘Lean’ Japanese Techniques” by Julie Jargon. This story provided a real-world example to which students could easily relate and which could provide immediate buy-in on the importance of Lean thinking in business. While I’m always on the lookout for a more recent article in the popular press to replace this one, I’ve yet to find one as engaging. I still use it today when discussing Lean. (The article is available at on.wsj.com/2ZFza53 but requires a subscription.)

DEFINING THE LEARNING OBJECTIVES

The Lean project requires students to study a department at our university or a local business that they interact with frequently, be it as a customer or an employee. On campus, typical entities include the admissions department, dining services, the bookstore, career services, the student recreation center, and the tutoring center. Off campus, it might be a clothing boutique, a favorite pizza parlor, or a local sandwich shop. The most unique subject to date has been the university’s art gallery, and the most common has been the bookstore—not surprisingly, since the students’ “institutional” knowledge of this business segment is particularly expansive!

When completing the project, students identify the university department’s or local company’s business strategy, develop a value chain, list critical success factors and measures, and, finally, apply Lean initiatives of value and cost/waste reduction. Plus, students gain other valuable educational opportunities by completing the project in the context of the following four cost accounting course learning objectives.

Learning Objective 1: Understand the principles of Lean thinking. To best help my students understand Lean, I first cover material regarding Lean principles in the textbook and infuse certain concepts, such as value-added activities, value-stream mapping, and empowerment, from the IMA SMAs. To supplement this knowledge, students read the Wall Street Journal article and highlight the principles of Lean thinking at Starbucks.

Learning Objective 2: Analyze a university department or local business and evaluate its current operations and processes. Related to value-stream mapping, on a broader scale, is the value chain. The value chain is a strategic tool that helps organizations understand their strategies, how to add value or reduce costs, and how to identify their linkages with suppliers, customers, and competitors. By conducting a value chain of a university department or local business, students form a template for many smaller value-stream maps and examine the pull-and-flow activities that propel the particular product or service forward.

Along with the value chain, balanced scorecards have become another important management accounting tool to enhance competitiveness. Balanced scorecards facilitate a greater understanding of Lean for that entity by linking strategic goals to financial and operational performance measures. As such, I ask my students to list important perspectives of the balanced scorecard with regard to their chosen entity and develop measures to achieve those goals.

Overall, the first and second learning objectives and related assignments provide a foundation for understanding the organization. In turn, students can devise more meaningful Lean recommendations, which is the third learning goal.

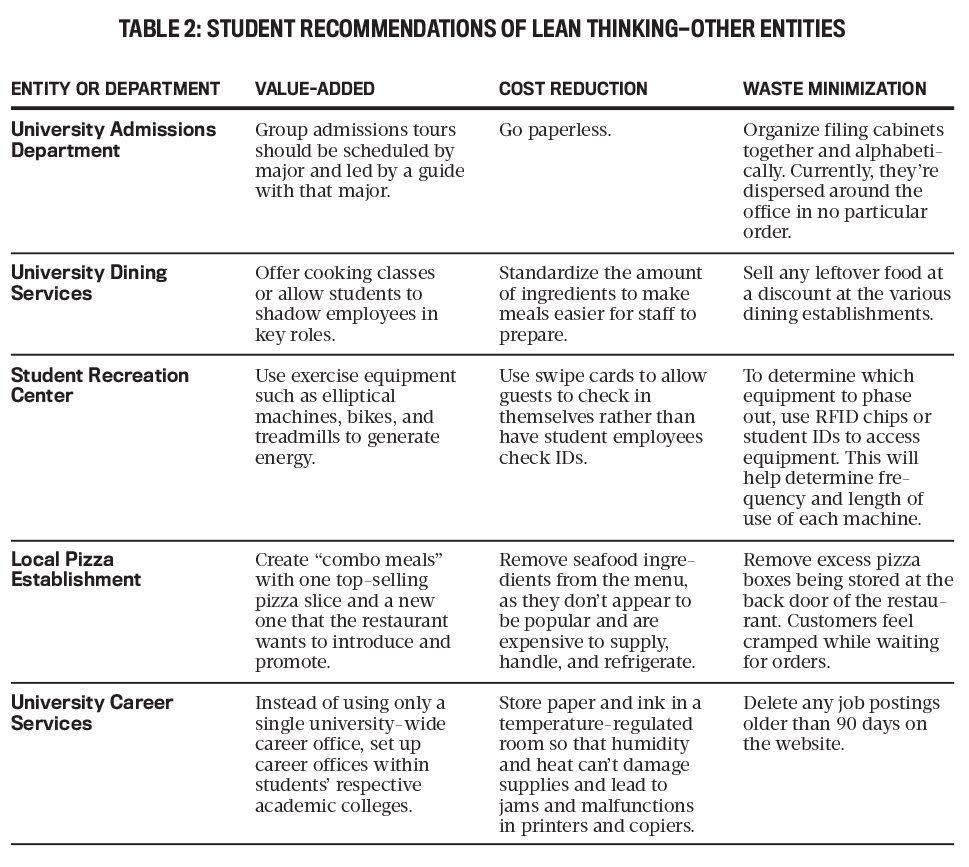

Learning Objective 3: Develop Lean techniques that the department or business can perform to improve operations. The ultimate goal of Lean is perfection, defined in this context as continuously improving by concentrating on value-added activities and eliminating all forms of waste. Lean techniques can be either in the form of customer-focused initiatives, cost- and waste-reduction tactics, or operational improvements. Students recommend ways the department or business can employ Lean initiatives. Tables 1 and 2 contain examples of these recommendations.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Students in my classes consistently come up with insightful Lean initiatives. In fact, in summer 2016, I shared some of their recommendations with our university’s CFO. As she reviewed them, she commented that many of the students’ ideas were the same as what the school’s hired consultants had proposed.

Learning Objective 4: Communicate the analyses through written responses. Despite the importance of communication skills in the accounting profession, a disparity exists between the expected level of competency and the actual writing ability of accounting graduates. Often, accounting educators rely on composition classes to teach necessary writing skills, but they themselves never ask the students to write anything for their own courses. It’s no surprise then that employers are frustrated by these communication deficiencies when students hit the workplace.

Like any skill, however, developing writing skills takes practice, practice, practice. That’s why I require my students to communicate their ideas to me in written form. Over the years, some students have lamented that it would be easier for them to present their analyses in charts or bulleted lists. But because I want them to sharpen their writing skills, I insist that their analyses be in the form of full sentences and paragraphs, conveyed in a limited number of pages—only one page for the first part of the assignment and no more than four pages for each of the three remaining parts (all of which I’ll talk about in more detail in the next section).

LESSONS LEARNED

More than 400 of my students (and counting) in upper-level cost accounting classes have completed the Lean project since the fall 2012 semester. In that time, I’ve tweaked the project to improve students’ learning experiences.

My first adjustment was making it an optional team project, though I soon realized that students could benefit from discussing their ideas with one another—especially if they chose the same business or university entity. As such, students can work in groups of up to three (team-oriented problem solving, for instance, is a principle of Lean), though I still permit some to work alone if that’s easier for them. Most choose to work in a group.

Second, I divide the assignment into four parts—strategy, value chain, balanced scorecard, and Lean initiatives—which are due throughout the semester. I recognized I needed to shorten the first assignment, the description of the entity’s strategy, to a maximum of one page, double-spaced. (As noted, the other parts of the assignment are a maximum of four double-spaced pages.) This first submission informs me of the students’ writing skills. By limiting it to one page, I can quickly assess whether they need additional coaching, either by me or by someone at our university’s writing center. I return these papers the very next class with guidance on how students can improve. This sets the proper tone for success before they tackle the next three parts.

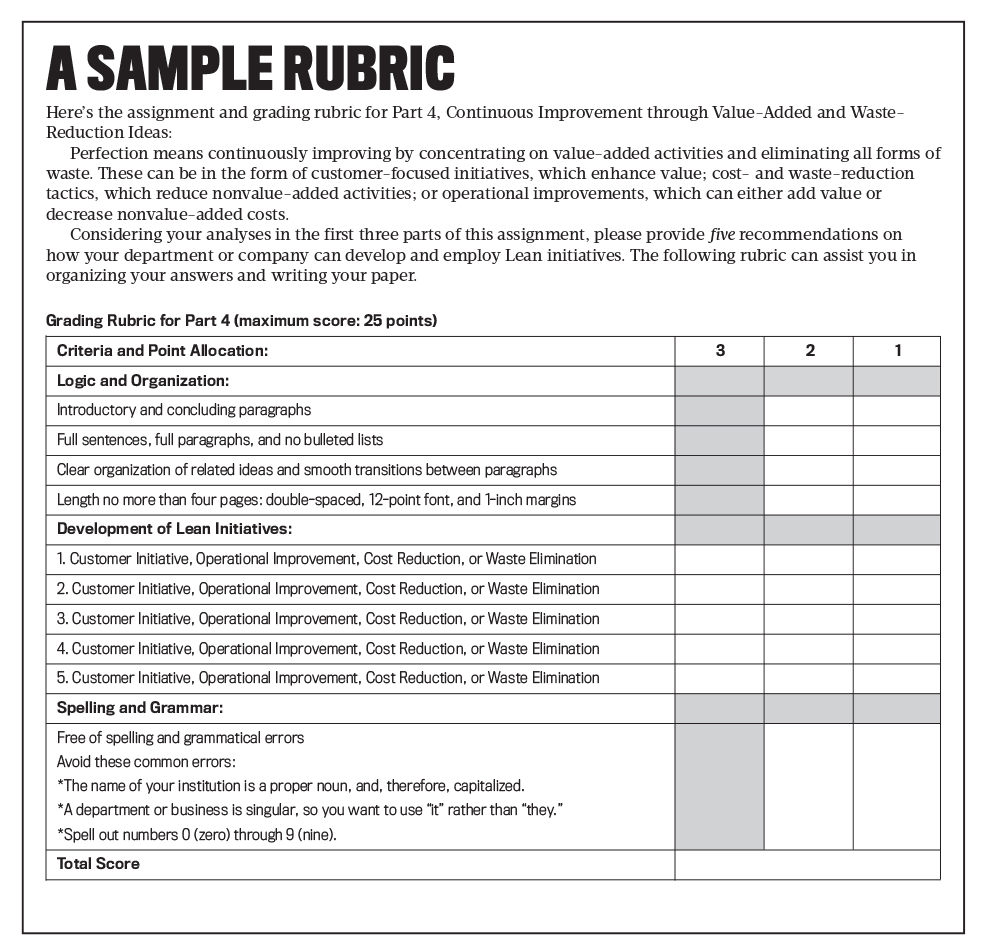

Third, when I began assigning the project, I referenced handwritten notes consisting of general ideas that I had hoped to see in students’ submissions. This rudimentary guidance added hours and hours to the time it took me to grade! As many instructors know, a well-designed grading rubric, a guide that lists criteria for assessing students’ work and distributed to them before assigning the project, can save enormous amounts of time for both the instructor and the students. Moreover, the students’ submissions are of higher quality when the teacher clearly communicates the expectations. I now include a rubric for each part of the assignment in the project document (see “A Sample Rubric”).

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Fourth, because the response to the Lean project has been so positive in my cost accounting classes, I have expanded it on a more informal scale in my online MBA managerial accounting course. Just like my undergraduate students, my graduate students can think Lean and arrive at clever value-added and cost-reduction strategies. In fact, a colleague of mine at a small public university employed the project in her MBA class, too, and confirmed that her students met the learning objectives.

Overall, my students never cease to amaze me with regard to how creative and valuable their suggestions are and how those recommendations embody the principles of Lean. Therefore, I want to thank all of my accounting students over the years who have educated me! Indeed, you have unleashed the power of thinking Lean.

August 2020