Management’s decision to make these discretionary disclosures is based on an internal cost-benefit analysis and may be driven by market demand, competitive pressures, opportunism, and other forces. In theory, if the cost associated with disclosure is less than the positive impact on the value of the company, the disclosure will be made; otherwise, it will be withheld. It is in the context of voluntary disclosure, more specifically in corporate quarterly earnings releases, that the use of non-Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) reporting originated and has since continued to expand.

The SEC requires that companies use GAAP to compile the financial statements that are included in mandatory quarterly and annual filings. Prior to the issuance of Regulation G, no similar restriction was placed on voluntary corporate disclosures. This often led to the overaggressive use of non-GAAP disclosures, resulting in misleading financial reporting in corporate earnings announcements.

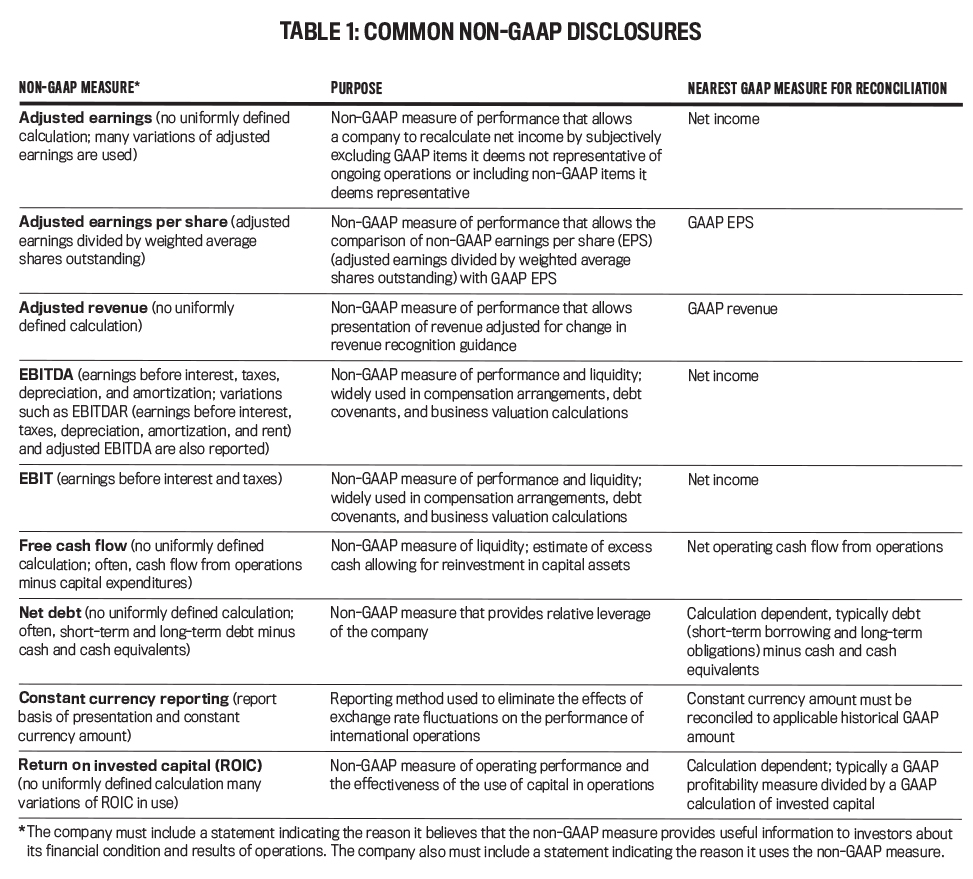

Because earnings announcements typically precede SEC filings and the market rapidly absorbs any new information, investment decisions were often made based on non-GAAP disclosures that presented the company in a disproportionately favorable light (see Table 1).

SELECTIVE DISCLOSURE

In the last two decades, the SEC has addressed most of the flagrant abuses of non-GAAP reporting in corporate quarterly earnings announcements. The provisions of Regulation G, for example, state that non-GAAP financial disclosures shall not contain untrue statements or omit statements of material fact. They must include the most directly comparable financial measure calculated in accordance with GAAP and require a reconciliation of the differences between any non-GAAP financial measure presented with the most comparable financial measure calculated and presented in accordance with GAAP.

And in 2016, the SEC, in issuing its Compliance and Disclosure Interpretations (C&DIs), revised guidance on the use of non-GAAP financial measures. This clarified and, in some cases, changed the existing rules for the use of non-GAAP financial measures, especially regarding the relative prominence of non-GAAP vs. GAAP disclosures in earnings announcements.

Most agree that the efforts of the SEC to establish rules and bring order to the previously unregulated use of non-GAAP measures have improved the quality of disclosure in corporate earnings announcements. Though significant progress has been made, companies often engage in a subtler type of non-GAAP reporting: selective disclosure. This is because earnings announcements are strictly voluntary disclosure and no SEC requirements exist regarding the content, timing, or audit of information included. These remaining loopholes must be closed as soon as possible to ensure that investors are consistently provided on a timely basis with complete quarterly financial information.

Periodic financial results were once communicated to the market exclusively through mandatory quarterly and annual filings with the SEC, but companies subsequently adopted the practice of reporting quarterly financial results publicly using earnings announcement press releases that, in most cases, preceded the SEC filings. This is due, in no small part, to corporations seeking to control the narrative and interpretation of their financial performance while attempting to allay the market’s demand for greater disclosure. Over time, quarterly earnings announcements have become progressively more expansive and are now the most regularly provided form of stand-alone voluntary disclosure of financial performance. The market has grown accustomed to being informed and updated on corporate performance in this manner, during the so-called quarterly “earnings season.”

The content of periodic corporate financial performance information, as well as the means and timing of its dissemination, has critical wealth-shifting implications as market participants rush to interpret and respond to the actual vs. anticipated results. The quality of disclosure contained in corporate earnings announcements varies widely as companies can effectively “tailor” their message through the use of non-GAAP disclosures, giving prominence to more favorable metrics and the selective inclusion or omission of meaningful financial information.

GROWTH IN GAAP ALTERNATIVES

While GAAP set out the standards by which corporate financial reporting is to be formulated, many corporations choose to disclose alternative measures of performance in their earnings announcements to adjust for onetime events, unusual items, or a wide variety of other reasons. These non-GAAP measures are most often used to adjust GAAP net income, but are also presented for revenue, cash flows, operating segments, and other financial items.

Empirical evidence reveals that the use of non-GAAP disclosures has grown dramatically over time and is now widespread. According to the Audit Analytics report Long-Term Trends in Non-GAAP Disclosures: A Three-Year Overview, the number of S&P 500 companies that presented non-GAAP disclosures at three different 10-year intervals were: 59% during 1996, 76% during 2006, and 96% during 2016.

A major driver of this phenomenon is that non-GAAP disclosure generally produces more favorable results than when measured under GAAP. Supporting this notion, Feng Gu and Baruch Lev report in “Surprise: Investors Like Non-GAAP Earnings” that 80% of the S&P 500 companies they sampled during the fourth quarter of 2015 disclosed non-GAAP earnings and that these exceeded GAAP earnings by about 24%.

TWO SIDES TO EVERY STORY

Company management and other proponents sometimes argue that non-GAAP disclosure serves a vital communication function: clarifying complex GAAP-based disclosures and providing a more accurate portrayal of companies’ permanent or “core” earnings. Management can use non-GAAP disclosures to provide insight to investors on critical metrics used internally to manage its business. Advocates of non-GAAP disclosure also justify its use as a means to compensate for the perceived limitations inherent in GAAP. For example, critics point out that GAAP financial statements only reflect what can be reliably measured, resulting in nonrecognition of many internally developed assets, regardless of their strategic value to the company.

Costs, such as research and development and advertising (leading to customer acquisition and development of valuable customer lists), are expensed when incurred because it can be difficult to identify the precise future periods benefited. In their 2018 book, Financial Statement Analysis & Valuation, Peter D. Easton, Mary Lea McAnally, Gregory A. Sommers, and Xiao-Jun Zhang suggest that this results in significant understatement of assets, particularly the knowledge-based assets of technology companies.

Whether or not you accept the assertion that there are certain limitations in GAAP, at a minimum they are, in fact, based on standards meant to promote consistency, relevance, reliability, predictive value, and transparency—in other words, quality accounting disclosures. The practice of using non-GAAP disclosures is, however, controversial because historically there have been no precise standards for calculating non-GAAP adjustments or reporting. Deviations from GAAP are often arbitrary and can result in non-GAAP measures that lack consistency from period to period.

Vocal critics of non-GAAP financial reporting have characterized the practice as a less-than-transparent means to meet performance targets and otherwise mislead investors (see Nilabhra Bhattacharya, Ervin L. Black, Theodore E. Christensen, and Richard D. Mergenthaler, “Empirical Evidence on Recent Trends in Pro Forma Reporting,” Accounting Horizons, March 2004).

Companies continue to have significant latitude as to which components of GAAP earnings they choose to include or exclude from “adjusted” earnings. A GAAP loss, adjusted for items that management feels aren’t representative of true company performance, can be converted to a non-GAAP profit by adjustment or exclusion. Even in the post-SEC regulation and guidance environment, the reporting of GAAP and non-GAAP versions of what is presumed to be a single measure is likely to cause confusion among investors and other users of financial statements.

THE SEC INTERVENES

Controversy over the use of non-GAAP disclosures in quarterly earnings announcements is hardly a new phenomenon; over time, it has been consistently identified as a potential problem by leading members of the SEC. General concern over the erosion in the quality of reported results and related disclosures was expressed more than 20 years ago by then SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt in his speech titled “The Numbers Game”.

Levitt warned that the desire to obscure actual economic results and otherwise manage earnings can be facilitated through the misuse of non-GAAP financial reporting. Over the years, consternation over non-GAAP reporting has been expressed at various times by SEC chairs Harvey Pitt and Mary Jo White as well as chief accountant Lynn Turner. More recently, there was evidence of lingering concern about the misuse of non-GAAP financial disclosure among SEC leadership, despite the fact that Regulation G has been in place for more than a decade.

The SEC’s tolerance for what it characterized as abusive and misleading use of non-GAAP disclosure in corporate earnings announcements waned and was destined to change in the near term. The impetus for the SEC’s focus on non-GAAP financial measures was likely registrants’ increased use and prominence of non-GAAP measures, the nature and magnitude of the adjustments, and the increasingly large differences between the amounts reported for GAAP and non-GAAP measures. In the wake of its persistent warnings of crackdowns on registrants that use non-GAAP financial measures inappropriately, the SEC acted by issuing the aforementioned C&DIs in 2016.

Based on the commentary of its senior leadership, the SEC is satisfied with the formation and implementation of its rules and regulations addressing non-GAAP disclosure (see, for example, Wesley Bricker and Marc Siegel, “Transition Issues, Non-GAAP Measures, and Disclosures,” The CPA Journal, July 2016). But managers continue to have an informational advantage over investors and have incentives to maximize the value of the company as perceived by investors. Under these circumstances, managers can strategically and selectively disclose information in their earnings announcements.

Prior research has demonstrated that managers voluntarily disclose information in their earnings announcements that facilitate investor valuation, particularly when there’s uncertainty surrounding future earnings. When a manager feels it’s in the company’s best interest to do so, she or he will selectively limit the extent of disclosure in their quarterly earnings announcements.

For instance, a company that has narrowly met analysts’ estimates for its earnings, and only by the creation of discretionary accruals, would likely want to focus attention on its earnings per share and income statement and away from its statement of cash flows. The company might simply omit the GAAP-based statement of cash flows (with its reconciliation of net income to cash flows from operating activities) from its earnings announcement. Omission of one or more GAAP financial statements also raises ethical concerns.

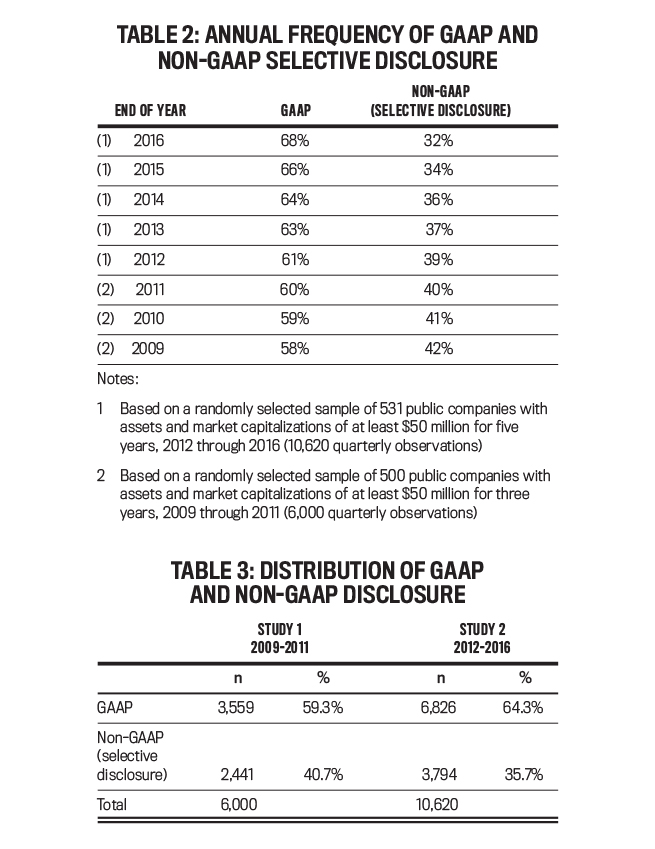

I worked on two studies (one collaborating with other researchers, the other conducted on my own) intended to estimate the extent of non-GAAP selective disclosure in earnings announcements (see Table 2). The first, based on a randomly selected sample of 500 public companies with assets and market capitalizations of at least $50 million, for the three years 2009 through 2011 (6,000 quarterly observations) revealed that nearly 41% selectively withheld either a balance sheet or statement of cash flows from public disclosure at the time of their earnings announcement. (See Thomas D’Angelo, Samir El-Gazzar, and Rudolph A. Jacob, “Firm characteristics associated with concurrent disclosure of GAAP-compliant financial statements with earnings announcements,” Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, May 2018.)

The second study, based on a randomly selected sample of 531 public companies with assets and market capitalizations of at least $50 million, for the five years 2012 through 2016 (10,620 quarterly observations), showed that about 36% of companies continue to consciously omit a balance sheet or statement of cash flows from public disclosure at the time of their earnings announcements (see Table 2). Despite relatively more companies using GAAP in the later periods, it’s clear that the problem of selective disclosure persists in significant numbers (see Table 3).

Of course, companies must eventually fulfill their mandatory quarterly and annual reporting requirements with the SEC, in which they’re required to include the full complement of GAAP-based disclosures. The problem for investors is that companies usually announce their earnings in advance of the SEC filing, and thus the information conveyed in the earnings announcement may well be lacking critical elements. But because investors have become increasingly “fixated” on companies’ earnings performance vs. analysts’ estimates, the response to the earnings announcement has been shown to be significantly greater than that of the subsequent, yet more comprehensive, SEC filing.

The exponential growth in information outlets and the speed with which information is now circulated has potentially intensified market response to the information contained in quarterly earnings announcements. Companies’ use of selective disclosure in their earnings announcements allows management to effectively delay the release of information that doesn’t support its performance narrative, thus continuing to exacerbate the issue of information asymmetry for investors. By the time the SEC filing finally does occur, it’s often well after the market’s most significant reaction to the earnings announcement and too late for investors who prefer to make timely portfolio decisions using the complete information.

CLOSING THE NON-GAAP GAP

Now that the SEC has substantially improved the corporate information environment through the implementation of Regulation G and subsequent guidelines, this is an opportune time to ensure that investors are provided with all the information deemed relevant by management, at a single time, within the quarterly reporting cycle. In other words, the market should no longer be subjected to the fragmented financial reporting that results from opportunistic, selective disclosure.

If management believes that information is important enough to disclose, whether GAAP-based or not, it should become available for public interpretation at the same time. Allowing management to engage in selective disclosure opens the door to the omission of material information and potential manipulative behavior.

Many others have expressed a similar viewpoint. Investment industry professionals have been critical of companies practicing partial disclosure in earnings announcements due, in part, to the disproportionate market response resulting from the instant analysis of earnings data released without the context provided by the more fulsome disclosure of cash flow information. (See, for example, Erik Randerson, “In an era of full disclosure, what about cash?” Financial Executive, September 2004.) In fact, many financial analysts agree that cash flow data is necessary to effectively evaluate earnings quality and, along with the balance sheet, is potentially more important than the income statement in assessing overall company financial health.

The SEC, through its Advisory Committee on Improvements to Financial Reporting Subcommittee, examined issues related to the earnings release, more specifically, the consistency, understandability, timeliness, and continued availability of reported information.

A key recommendation was the inclusion of a complete set of GAAP financial statements in quarterly earnings announcements. The continuing problem of selective, piecemeal disclosure is perhaps best summed up by the CFA Institute: “Analysts consider the three financial statements—the balance sheet, income statement and cash flow statement—taken together to be critical in gaining an accurate picture of a company’s position. But too often they have to wait until weeks after the company’s earnings announcement, when the companies file their 10-Ks or 10-Qs, to look at the other two financial statements. By then, the announcements are under the radar screen of most media” (bit.ly/3aLWxha).

ALL TOGETHER NOW

When I served as the chief accounting officer at a public company and had primary responsibility for financial reporting, I became increasingly skeptical of the market’s obsessively narrow focus on quarterly earnings per share. The income statement and its calculation of accrual-based earnings are an important but singular measure; critical dimensions of performance are also provided by other financial statements. For example, because cash flows from operations is designed to reflect the cash effects of income determining items, it serves as an effective cash-based corollary measure to earnings. Users can better assess the quality of earnings once the impact of companies’ discretionary accounting choices and accruals are removed.

An important lesson learned from my corporate reporting experience and analyzing major accounting frauds was that investors who make decisions based solely on earnings do so at their own peril. Financial statements are interrelated and report the effects of the same transactions from different perspectives. They each provide a unique set of information to the market that isn’t otherwise directly obtainable from any other individual statement. Financial statements are designed to be complementary and are meant to be interpreted concurrently.

It’s a company’s responsibility to make available a comprehensive package of disclosure, which should include GAAP-compliant financial statements as a component of its quarterly earnings release. Most companies have already adopted this disclosure strategy, so complaints about additional reporting burden would seem unfounded. Management would be able to report performance using both GAAP and supplemental non-GAAP disclosures, if all SEC regulations and guidelines were adhered to.

To this end, many companies have implemented a system of disclosure controls to ensure compliance, consistency, and high quality of information through the creation of disclosure committees, usually made up of senior management, members of the audit committee, and others charged with corporate governance. Companies can bolster their credibility in the market by eliminating the intentional selective disclosure of financial statements within earnings announcements, improving the overall information environment for investors.

April 2020