In the April 2018 Strategic Finance article, “Maintaining Relevance in the Digital Age”, Raef Lawson and Larry R. White point out that management accountants bring a unique blend of skills and abilities to business decision making, including a holistic view of operations combined with a detailed understanding of costs and cost behavior, a deep business acumen, and their ability to use sophisticated quantitative and technological skills in decision making.

Management accountants can improve one class of business decisions that has returned to the forefront: global strategic sourcing decisions. In its traditional form, sourcing is mostly about the process of locating and contracting with suppliers (think procurement). But given that companies can source entire business functions, sourcing encompasses a lot more than procurement—it has morphed from a narrowly defined procurement/supply chain-related decision into a business entity-related decision.

When the word “global” is added to the decision context, the obvious implication is that suppliers may be selected from beyond the organization’s national borders; therefore, the sourcing strategy extends to offshoring as well. As one can imagine, when sourcing gets elevated to an entity-level decision, the consideration of risks at that level as well as the importance of incorporating strategy into the decision-making process become imperative. Against the backdrop of highly complex and rapidly evolving conditions affecting strategic sourcing decisions, management accountants now have an increasingly critical role to play.

SHIFTING SOURCING LANDSCAPE

Sourcing decisions were once so simple that the applicable decision calculus was intuitive and straightforward. If you could move operations to developing regions where wages were much lower, you did it; if you could outsource a product or a function at a lower cost than you could by completing it in-house, you simply did it. Furthermore, if a country across the globe could provide such arrangements better than you could (due to whatever distinctive capability it possessed), you promptly outsourced (better yet, offshored) without thinking twice.

Until recently, businesses assumed that, through outsourcing, they could capitalize on someone else’s cost advantage and distinctive capabilities and turn those into their own advantage. Businesses also confidently expected this “borrowed competitive advantage” to be sustainable—it was an era of easy pickings. As a result, at the beginning of the millennium, companies offshored parts, products, services, and entire business functions. But lately, conditions have changed dramatically, and a new business world order has emerged.

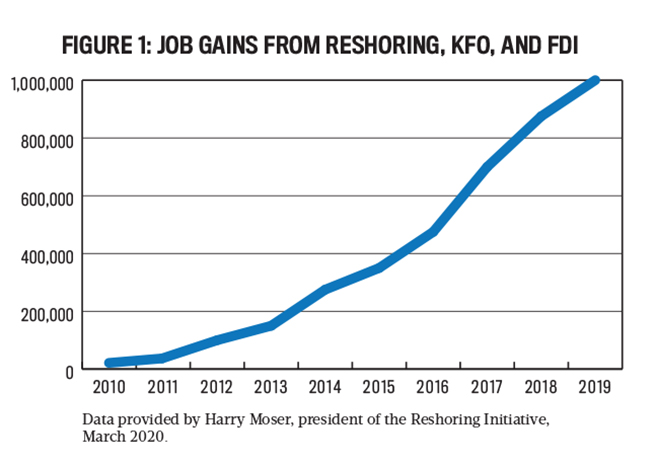

The Reshoring Initiative 2018 Data Report documented the announcement of 145,000 new U.S. manufacturing positions in 2018 from reshoring or foreign direct investment (FDI). Harry Moser, president of the Reshoring Initiative, revealed that there were documented announcements of a further 112,000 manufacturing positions in 2019 as a result of reshoring, FDI, or positions kept from offshoring (KFO). (The 2019 data report isn’t printed yet, but its data is available through the Initiative’s offices.)

This is particularly interesting because prior to this shift, U.S. manufacturing jobs peaked in June 1979 at 19.6 million positions, declining precipitously by 41% to a low of 11.5 million positions in February and March 2010 (see Figure 1). From January 2010 through December 2019, there have been announcements of 997,121 new U.S. manufacturing positions as a result of reshoring, FDI, or KFO positions.

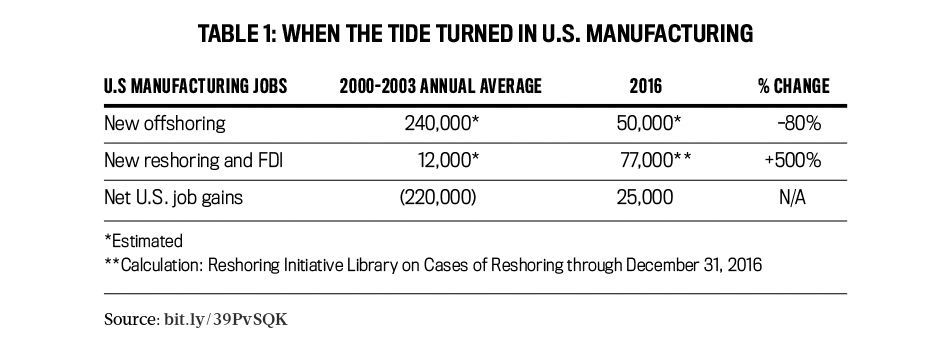

In the same time frame, total U.S. manufacturing positions grew by 1.413 million positions. So reshoring, FDI, or KFO decisions accounted for almost 71% of the growth. The turning of the tide from 2000 to 2016 (latest available offshoring data) appears in particularly sharp relief in Table 1.

So, the question is, why was there such a dramatic shift? Economists, academics, and policy makers in general, as well as politicians and business executives, have identified many reasons. Some, such as the steady wage growth in China, are based on economic data; other reasons, such as favorable, protectionist rules for local businesses in developing countries, are based on harsh realities—often referred to as “opportunism” in outsourcing—faced by companies that initially reshored.

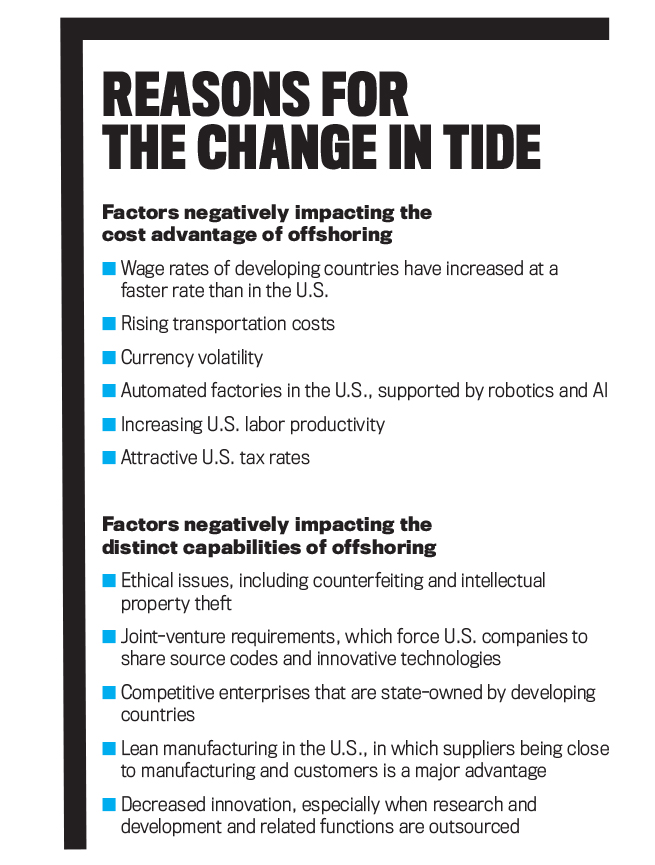

“Reasons for the Change in Tide” (see below) catalogs some of the key factors that caused the tide to change from offshoring to reshoring. Those factors are separated under the two reasons that companies initially chose to offshore—cost advantage and distinct capabilities. The bottom line is, no matter which way the information is dissected, so-called “borrowed competitive advantages” haven’t been sustainable advantages for the borrower (i.e., the companies that did offshore sourcing).

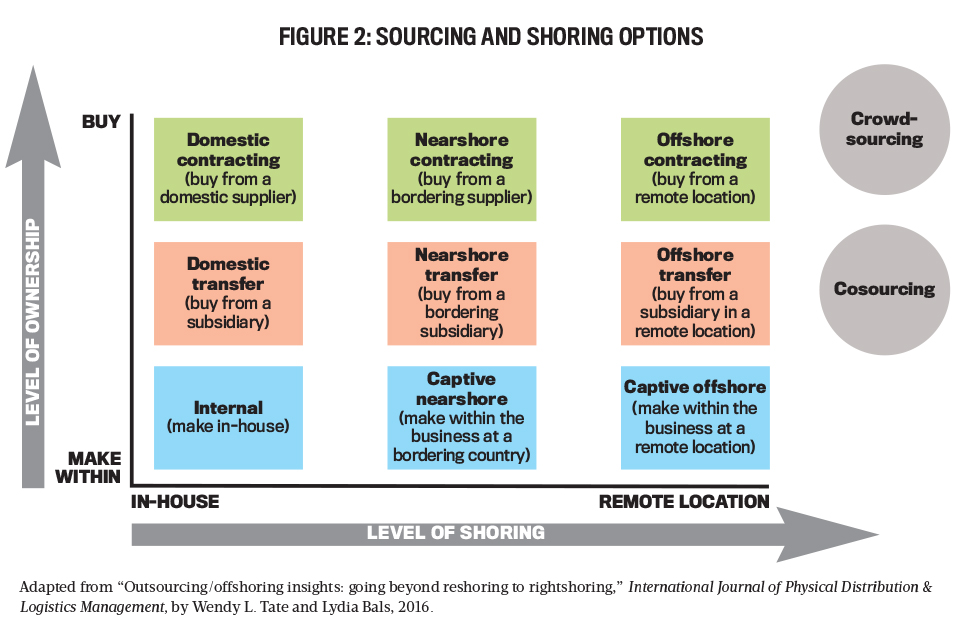

Further complicating the scenario is the range of nuanced sourcing options now available to companies. It’s no longer a choice between internal production and offshored production. Imaginative and innovative approaches command a premium during any period of business disruption. Accordingly, management accountants need to think creatively in order to capture all the choices related to sourcing, especially as rapidly growing internet-centric business culture and changes in the global business environment increase the available options.

In this day and age, companies should look beyond the in-sourcing/reshoring extremes and explore innovative hybrid options like cosourcing and crowdsourcing. Figure 2 illustrates some conventional as well as unconventional sourcing options, taking into account both ownership and distance (level of shoring). The new hybrid options, cosourcing and crowdsourcing, can be practiced without the conventional boundaries.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Another consideration in sourcing decisions is the type of work being sourced. Due to the once-widespread assumption that outsourcing/offshoring is always advantageous, companies outsourced/offshored core processes such as design, engineering, manufacturing, marketing, and accounting. The blind rush to offshore resulted in intellectual work being outsourced across continents, and for some companies this led to disastrous outcomes and ultimately to reshoring. Motivated in part by concern for its intellectual property, for example, Whirlpool brought its mixer-making back from China to Greenville, Ohio. For similar reasons, Otis Elevator brought back manufacturing from Mexico to Florence, S.C.

“Reshoring/KFO in the U.S.” (see below) shows a number of major corporations, after offshoring considerable intellectual work, are now reshoring. For some companies, the results were damaging. Most of the currently dominant television brands began as outsourced manufacturers for the then-dominant U.S. manufacturers. Zenith and RCA, for example, basically trained their competition through the sharing and outsourcing of their intellectual work.

In “Offshoring, Overshoring, and Reshoring,” an article published in the 2017 book Breaking Up the Global Value Chain, Gwendolyn Whitfield highlights the dangers of overshoring: “Defined as the progressive reliance on overseas suppliers for more high-value activities in the value chain, overshoring results in broad dependency, diminished organizational capacity, and competitive vulnerability.” The sourcing/shoring landscape isn’t just shifting in the United States. In fact, almost all economies are facing far less simplistic sourcing realities, thereby transforming sourcing/shoring decisions into a complicated affair that warrants a great deal of thinking prior to doing. Businesses, as a result, will turn to management accountants to sift through and isolate all relevant factors and facilitate sourcing/shoring decision making within a strategic and global context.

A NEW DECISION MODEL

Given the rapidly evolving landscape, increasing sourcing options, the business functions being considered for outsourcing, and strategic contexts for making such decisions, management accountants will benefit from the support of a well-formulated decisional framework that provides clear guidance in answering the question, “How exactly do we navigate global strategic sourcing scenarios?”

Sifting through the possible solutions is an enormous undertaking. Management accountants must carefully examine exactly which functions, products, or services are good candidates for outsourcing/offshoring. Isolating candidate functions, products, or services is best approached as a screening and sorting decision made from a strategic perspective.

In terms of management accountants’ responsibility, higher-order critical thinking skills are needed in such contexts. To this end, the value creation-criticality lenses (VCCL) framework can assist. This two-stage framework will prevent companies from repeating the mistakes made in the past. They won’t outsource just because it’s cheaper or just because the supplier has some distinctive capabilities.

In addition, management accountants won’t have to spend their time gathering cost data and performing detailed quantitative analysis on every sourcing candidate; rather they will do analysis only on the candidates that passed the screening and sorting phase. The VCCL framework permits efficient, effective processing of options in a rational, deliberate manner. The screening and sorting framework also allows isolation of items that make strategic sense to outsource. Instead of looking at traditional criteria of cost/benefits or distinct capabilities when making sourcing decisions, the proposed model introduces twin dimensions—value creation and criticality—as overarching but independent criteria.

VALUE-CREATION LENS OF THE VCCL

Value creation is ultimately the reason for business existence, and it’s the most important measure by which the organization’s goals and accomplishments are evaluated. Questions regarding what constitutes “value” are subject to debate and can potentially be measured using diverse metrics and indices such as market value, book value, and future performance—all of which are economically grounded and attempt to measure the shareholder value and return on investment.

Traditional outsourcing decision models based on transaction cost economics were solely based on shareholder value considerations. Even the resource-based view models, which are based on the core-competency approach (i.e., companies should concentrate on a set of core competencies and outsource other processes), are focused on short-term shareholder value creation.

Value creation should create value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders. It therefore involves the interdependencies between a company’s competitiveness and performance as well as those within communities of stakeholders. It reflects broad environmental, social, and governance (ESG) perspectives and is consistent with a sustainability orientation. (See “ESG and Sustainability in Sourcing Decisions.”)

After all, businesses shouldn’t make sourcing decisions based on “borrowed competitive advantages,” as those may not be sustainable in the long run (more and more companies are realizing this, as reflected through the reshoring statistics). Sustainable, long-run value creation for all stakeholders is one aspect that distinguishes the VCCL from existing frameworks. The value-creation lens involves screening and sorting.

Stage 1, Screening and Sorting: A management accountant will first look at the outsourcing candidate (business function, task, process, product, or service) through the value-creation lens. In this stage, there’s the need to bake in cost-benefit and risk considerations to prioritize the decision implementation. Pick those functions, products, or services that qualify through the screening and sorting process (potential candidates for outsourcing/offshoring) as economically beneficial to outsource/offshore and also ascertain the optimal ordering or sequence of such activities and arrangements.

CRITICALITY LENS OF VCCL

Next, the candidate functions, products, or services will be viewed through the criticality lens. Only the sourcing candidates (functions, products, or services) that pass through this screening will be subjected to further analysis.

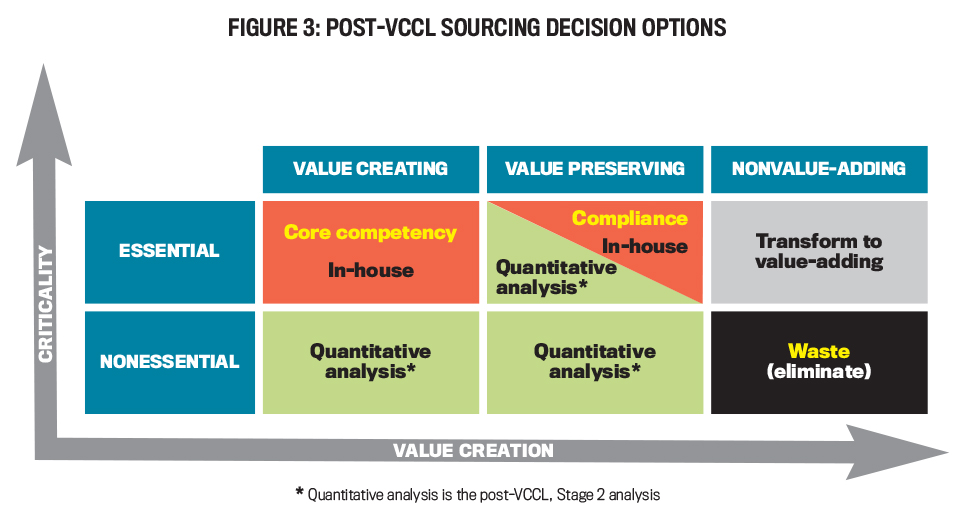

Stage 2, Post-VCCL Quantitative Analysis: The growing sophistication required for outsourcing/offshoring decisions suggests the need for increasingly refined quantitative models to analyze global sourcing decisions. All business functions can be separated into two categories: essential and nonessential. Essential functions are those that, if interrupted or poorly executed, will lead to business failures. Businesses shouldn’t expose these functions to opportunism often associated with offshore sourcing. On the other hand, not all companies will possess distinct capabilities with respect to all their essential functions.

In other words, just because someone else may have better capabilities than yours, you shouldn’t necessarily outsource these critical functions. These are the functions in which companies ought to invest in and grow to attain sustainable internal abilities, as opposed to depending on “borrowed competitive advantages.” Every organization that wishes to have sustainable success should have a screening and sorting framework or a well-defined process to identify its essential activities.

In Figure 3, the sourcing options resulting from the application of the VCCL to the global strategic sourcing decisions are shown. Basically, 1) outsourcing candidates should be evaluated in terms of criticality and stakeholder value creation, 2) the candidates should be positioned appropriately in a compare-and-contrast scenario suitable for evaluation, and 3) the appropriate decision should be made from there. Here are a few models to consider:

Total Cost Ownership (TCO) Estimator:The Reshoring Initiative offers a free online tool called the TCO Estimator that encourages managers to consider costs beyond total landed product cost (TLPC). TLPC has traditionally been the key consideration in sourcing decisions. This tool helps companies account for all relevant factors, such as overhead, balance sheet, risks, corporate strategy, and other external and internal business considerations in order to determine the true total cost of ownership.

Cost Differential Frontier (CDF) calculator:Researchers from the University of Lausanne used quantitative financing techniques to create the CDF calculator for determining how much lower the price of offshoring must be to compensate for the higher risk brought about due to the longer lead time of offshored products. Longer delivery periods for the offshored product require a longer time period between estimates of demand and product delivery, typically reducing the accuracy of the demand estimate and raising the risks and costs of stock-outs and overstocks. The U.S. Department of Commerce has introduced CDF to U.S. companies.

Assess Costs Everywhere (ACE):The U.S. Department of Commerce maintains the ACE website that provides a comprehensive tool kit and an analytical framework to estimate a variety of costs relevant to outsourcing and offshoring.

These tools provide valuable information and potentially alert management accountants to hidden costs as well as risks that may impact outsourcing decisions. These are useful Stage 2 tools to use after the Stage 1 VCCL screening and sorting decisions have been made.

DIRECTIONS FOR THE FUTURE

With the VCCL framework, management accountants can deviate from the status quo and use a more dynamic framework to guide strategic decision making related to global sourcing. As the economic landscape changes, what constitutes value creation may well change, as will the sourcing options available and the types of service providers and alliance partners.

If management accountants remain vigilant to such changes, they can suitably customize and adapt this framework to make global strategic sourcing decisions leading to sustainable results. In the final analysis, those who routinely think outside the box will typically succeed over their peers. Following the lead of the software programming industry, where open source is common (e.g., development of Linux), insourcing, outsourcing, cosourcing, crowdsourcing, and many other sourcing options may become viable options.

Recognizing that properly conceived and implemented crowdsourcing may reduce cost while increasing options and the scope for creativity, not surprisingly, several organizations have already resorted to crowdsourcing in this age of empowered consumers.

April 2020